Someone once told me that every Los Angeles story becomes a real estate story.

You meet a man in a leather jacket under a tree. He gives you his cellphone number. Later, he calls you to tell you he’s been involved in an accident and that’s why he did not receive your noncontingent offer and sold the house you wanted to buy to someone else. Your co-worker turns to you and says, “While I was doing shrooms in Joshua Tree, I suddenly realized that clouds are essentially sky rocks and that if my mother sold her house in Porter Ranch, we could maybe go in together on an Eastside duplex.”

I promise this is not one of those stories.

“Look at the bones on this, it’s perfect for an ADU,” he said, looking at the garage. “They don’t make 2-by-4s like this anymore, we could make a very special little house. It could be your office!”

We had just purchased our first home, a cozy 1920s two-bedroom house. When we finally closed on it, I was five months pregnant with my first child. I hugged the old oak tree in the front yard, feeling immensely grateful and fortunate to have a place that was ours. Owning a home gave me an unwavering sense of belonging, finally somewhere no one could make me leave. I dramatically deleted my Zillow account and said so long to all the agents I’d courted, who summarily ignored the offers I’d sent out.

It hadn’t occurred to me that there was something that needed to be addressed immediately. That thing was an empty, windowless garage sitting innocently on the corner of our newly acquired yard.

I was instantly, firmly against the idea of it. What is so bad about having a garage? I love garages. They are cool in the summer. You can store junk inside of them. You can stockpile food. They keep leaves and squirrels off your car, even if ours was technically too long to fit inside. Then there were the mechanics of how to go about turning our garage into a little house. Achieving this sounded operationally cumbersome, to say the least.

We will do the minimal amount to it, he promised — a blatant lie.

Why would anyone willingly take this on during a pandemic? Wouldn’t there be supply-chain issues? What if it took forever and cost all the money we have left?

“What about my parents?” he asked. “What if they want to meet the baby? Where would they stay?”

The bond between grandparents and grandchildren, that they would need one another, was something I assumed was universal. My maternal grandfather carried my backpack for me every day to school in Changchun, China. I slept between him and my grandmother in their bed while my parents went to work abroad. In the first phone calls home after my family immigrated to the States, in 1992, I cried without sound, so difficult to fathom our new distance. Three years later, when I finally saw my grandparents’ faces in the crowd emerging from the walkway at the international terminal at LAX, I was already thinking how difficult it would be to send them back, how much I wanted them to stay as long as possible.

The last time my paternal grandparents came to visit us in my parents’ house in Hacienda Heights, they took care of me for a year and a half. They stayed until they overstayed their visa and became undocumented because that’s how much they couldn’t bear to leave us. When they finally got on the plane to go home to China, it was with the knowledge they’d never be able to return to the United States again.

Like many immigrants, the people my husband and I loved the most were farthest away. If we wanted my husband’s family to come from Hong Kong to meet our unborn child one day, we’d need to provide them a place to stay.

The baby could sleep in our room with us, I said. It’ll be more than comfortable.

California homeowners have the right to build at least two ADUs on their property. But naturally, there are rules and costs. Here’s a guide.

Even then, I knew the outcome I was trying to outrun was inescapable. He was getting that demented, faraway look in his eye. He started framing windows with painter’s tape. He was pulling tile samples and color-matching paint. The garage was looking like toast.

“I’ll get it done in three months, tops,” he said confidently, “Isn’t this why you married an architect?”

It’s true, I married an architect, which is why I knew the optimistic time frame was a red herring and a trap. Architects care about details most people would never notice. It takes them a year of research to buy an expensive pair of glasses, which they break immediately by falling asleep in them. They rank sliding doors in terms of acoustics. They switch out the laces in their sneakers but will eat the same lunch every day. You can depend on them because they are used to being abused by clients. It’s different for every architect, but 20% of their capacity to feel human feelings is sacrificed to the craft. You might not even notice at first but trust me, those human feelings are gone.

When I met my architect, Paul, I became friends with his architect friends, and sometimes found myself volunteering to translate their feelings to the world at large. Then, I moved in with my architect and had to put up with his obscure references to plaster, to the way he makes meticulous paper models so he can design around the way the shadow falls across a wall during a site-specific sunset. Since 2009, I have taken trips to Japan to feel Tadao Ando’s concrete, to Guadalajara to look at early Barragán. I’ve been on the daylong train ride from Paris to Belgium just to stare at SANNA’s aluminum paneling. There’s this bathhouse in Switzerland that all architects go to for pilgrimage, and I’ve been there too, mostly making fun of them.

Almost against my will, I began to recognize the analogies between materials, the balance of the right visual contrast and that unexpected textures, side by side, can set a mood and create a vibe. Not long ago, my architect and I drove across America to walk through houses by Frank Lloyd Wright and experience Donald Judd’s sculptural proportions. We talked about the magic of a well-designed space and what it would be like to own our own house one day. This was when we first moved from New York to Los Angeles, when owning our own home was just a vague possibility.

In New York, the architects I knew talked about storefronts and restaurant build-outs. Here, they talk about ADUs. The ones they are building for other people inside, beside and above their garages. They rant about permits and licenses. There’s a guy in the permitting department they all know, and they curse his antiquated multisyllabic name like he’s a warmongering dictator each time their plans don’t pass his inspection.

Architects are always trying to feature something no one needed nor knew to ask for: an exterior spiral staircase painted Yves Klein blue. An indoor tree. An outdoor bathtub. Ours would feature a floor-to-ceiling sliding door that disappeared into the walls and seamlessly into the floor.

Of course, our initial plans for the ADU were rejected. So were the second plans. Paper models were remade. Building code specifications were studied. At some point, stay-at-home orders in Los Angeles were put in place. The streets around our house became utterly quiet. Flights from Asia were banned. There was no choice but to informally abandon the plan and give up on the ADU.

My daughter was born deep in the first wave of the pandemic. She emerged like a perfect scoop of ice cream. We stayed inside our still half-furnished house and looked at her face and saw in her all the people we missed the most.

Were her crescent eyes like her great-uncle? Were the upturned corners of her pink lips just like those of her grandmother, cooing at her through the phone screen?

As our first child grew up, her grandparents’ visit kept being pushed back, as waves of infection and variants came and went. Paul became absorbed with making our daughter laugh and trying to convince her to use her arms. I tried to write my novel, even though sitting down still made my C-section scar sing with pain.

During this period, I, like everyone else, thought about baking sourdough bread. I rolled out my own scallion pancakes. Friends sat six-feet apart in our backyard, in a cloud of mosquito spray, and talked vaguely about revolutions. The garage remained a garage.

Then the vaccine rollout began. All the world seemed to rush with hope for the end of the pandemic and the possibility of travel. Not to be outdone, I got pregnant, again.

Situated behind grandma’s house, this Eagle Rock ADU is perfect for a young family of three.

Plans for the ADU were reignited. This time, the goal was revised for his parents to visit when our son was born in the fall. Would it even be possible to complete the project before winter?

I pictured how we were going to fit these grandparents into our existing two-bedroom house. The two babies are in separate pack-and-plays, one in the breakfast nook, one in the hallway. The grandparents would, of course, sleep in the en suite bedroom, and we would take the other bedroom. Maybe I could sleep with one of the babies in the bathroom. Could I fit a bed in the shower?

By March 2021, flights from Asia were no longer banned. But even as COVID-19 restrictions loosened everywhere, my in-laws, both in their 70s, would need to be quarantined, by law, for three weeks in a hotel after they returned home. So their stay with us would need to be at least a few weeks long. Holding their enormous sacrifice in mind, I wanted to make sure they were comfortable during their stay.

They would need a little house. We would need an ADU.

The project was personal for him. He hadn’t lived with his parents since he was 16 and sent to boarding school. The goal was to create a warm and comfortable home but with a built-in clear separation. The ADU would stand alone; it wouldn’t mimic our actual house in shape or color. The two structures were to be cousins rather than siblings.

“I can get it done in four months,” Paul said this time, as he rushed back to hover over his computer. He walked me through the 3-D construction drawings. After he lined up plumbing and relocated outlets to code, we used an avatar to wander around this digital rendering.

Paul thinks of buildings through apertures, where and how the light comes in. The garage was shaped like a house, and he wanted it to have its own distinct mood. Four skylights would be punched through the roof to frame the sky and clouds. A clerestory window looked out at the branches of our olive tree. Up the library ladder would be the lofted second story, with a nine-grid tatami mat inset into the wooden floor for reading and meditation. The hideaway shades behind the screen door would serve as a projector screen. The babies could perform puppet shows for the audience on the deck below.

The idea was to blur the boundary between the inside and the outside, which is the essence of our California life. Inspired by the Japanese engawa, an in-between space where families gather after dinner for watermelon right outside where they’d head in for bed.

In the bathroom, rendered entirely in shades of green, a window would be framed out and in perfect symmetry with the mirror. The tiles would be a natural pigment of Roman clay.

He planned rimless recessed lighting, with outlet base plates that would disguise themselves in the Belgian plaster. The plaster would bear the hand of the person who made it. Its color is a warm beige, which would mellow and change with time.

Materials still had to be priced out. Dreams still had to be crushed. The original sliding door he wanted cost more than the entire budget of the ADU. We could only afford enough tiles for half the bathroom.

Tolstoy told us: “Spring is the time of plans and projects.” And spring was when we decided we could not wait any longer to begin construction.

The problem was we had not been able to find contractors who had time to take the job. The world was picking up, and construction was catching up. We were quoted not months but years to begin. I counted backward with both hands on my growing belly.

We weren’t going to make it. There was no way.

We finally interviewed a contractor who specializes in turning people’s garages into hydroponic weed farms. “We will leave that door on so it still looks like a garage, right?” he asked, shocked that we were not planning to grow weed inside. He looked at Paul’s carefully drawn plans and made fun of him in Chinese.

We’ll get it done in a month, the contractor said, and he was hired.

The weeks turned into months, the first month became the second, then the third.

Every day, I looked out at our debris-covered yard, the once formerly tidy little garage that now resembled a toothless head. One month! The contractors had promised. I repeated those two words and laughed maniacally.

In an innovative take on backyard “granny flats,” architects Melissa and Amanda Shin design an ADU that faces the street, while a two-story main house is installed in the back.

Meanwhile, my in-laws’ visit also was being pushed back due to the pandemic. Tickets were purchased and then canceled. I wondered: Would they visit before the baby was born, when the baby was born, or perhaps just weeks, months after the baby was born?

My ADU breaking point wouldn’t come for a long time. Not when the skylights had been installed incorrectly and were already beginning to leak water. My breaking point came not when it became too loud for a toddler to sleep inside the house, nor when it was too dusty to go outside with her in my arms. Not when the flooring was not leveled and had to have another entire layer of floor underneath. Not when a bucket holding down the second set of flooring flooded it again.

What next? As my due date approached, the wood for the deck could not be located. The toilet didn’t fit correctly, and it sat half in a box for months in front of our front door, waiting to be exchanged.

There comes a time in every ADU story where you think you’ve made a terrible mistake. Five months into the project, our contractors suddenly quit. Perhaps they had another, more lucrative hydroponic weed farm ADU to build elsewhere. Or they were just tired of our meticulous requests.

The bathroom floor was still flooded. The front door we ordered never arrived. The loft upstairs no one had even gone up to yet, and I was beginning to be afraid of it.

We should have kept the garage, I said unhelpfully.

My parents had to help Paul do the rest of the construction themselves, driving up every weekend to install cabinets and fixtures. Each day after work, Paul would be in the ADU sanding the walls until it got too dark to see. My mother chased my daughter around the dust-covered floors. My dad installed the curtains that would disappear into the wall. Everyone had to help lift the heavy pocket door that would make sure a sleeping grandpa would not be woken up by a showering grandma.

The last month of pregnancy, the days, minutes, seconds are five times as long. But apparently not long enough to finish an ADU. They were rushing to finish before the baby came, but then my son was born, and no visitors had arrived. Plane tickets were canceled, regulations were changed and the grandparents started wondering if they should fly during a global pandemic at all. This possibility sent Paul into a pit of despair.

Our daughter began to walk around. I held my breath listening to her laugh because it was the sweetest sound I’d ever heard and I desperately wanted her grandparents to hear it.

During this time, I rarely slept, as I was caring for a tiny helpless newborn. It was heartening to watch this little house continue to make slow and steady progress in our backyard. I watched the green tiles come to match the green floor; the piece of marble that was honed and then cut was finally fitted to the counter. After the plaster dried, our 1-year-old daughter ran around organizing all the wayward nuts and screws. I was genuinely concerned her first word might be “ADU.”

Light switches had to be changed into two-way, so grandparents wouldn’t have to get out of bed to turn off the front lights. A bed had to be placed just so, so the grandparents could wake up with a view of the garden, so they could see the children play even if they needed to lie down. A walk-in shower with no unnecessary steps was waiting for them, when, if they ever came.

Becoming a mother of two, I needed my own mother more than ever. She hoisted a baby on each arm while still trying to take business phone calls. Our little house was always packed with my family members. At all times, there seemed to be soup cooking, dumplings being wrapped and babies being serenaded to sleep.

In Chinese, 家, or jiā, the character for “family” is the same one for “home.” I understood the profound truth of that pairing.

Then finally, one evening early last November, my in-laws emerged through the long corridor of the international terminal at LAX, bringing with them the cool air of a truly faraway place.

As soon as they arrived at the little house their son had built for them, they went inside and slept until the following afternoon.

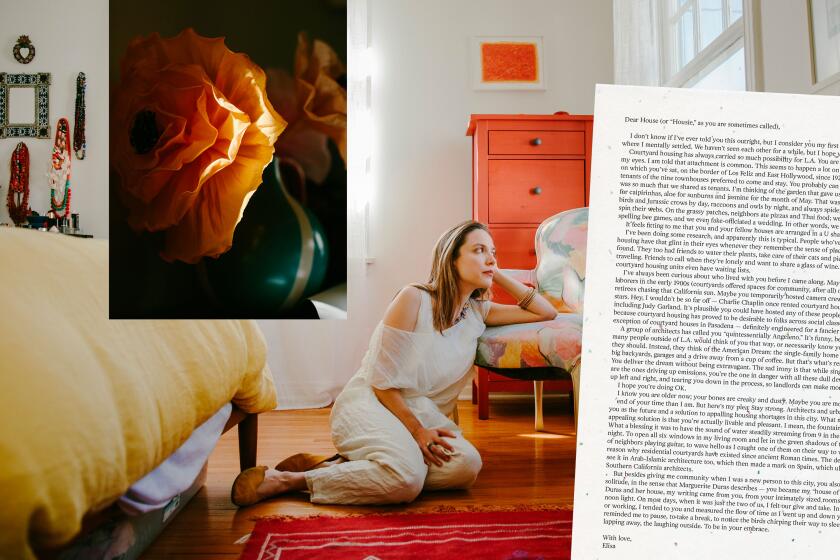

Critic Elisa Wouk Almino imagines an architectural future of open embrace

“Because the space was so quiet,” they said. “Because we feel so comfortable.”

The next day, they finally got to meet their grandchildren for the first time. We all cried as grandparents took turns holding each baby in their arms. The axis of our family seemed to shift at that moment. It would never be taken for granted that we’re all only a plane ride away from loved ones anymore. I felt the unimaginable loss of the last few years; no one can give back the moments these parents were robbed of being grandparents. And yet here we were, all together.

“It is like we know each other from another life,” her grandfather told me, as he carried his granddaughter around, pointing at cars and airplanes and giving these things names in a language she’d yet learn to speak.

We named the ADU “Grandparents’ House.” And much to everyone’s surprise and absolutely no one’s intention, my in-laws grew into the name. The day before they were originally set to leave us, Hong Kong banned all flights from the U.S. as a precaution against Omicron. The grandparents’ six-week visit got extended by weeks that turned into months and months, with no departure date in sight.

For a long time I thought it would be impossible for my parents and Paul’s parents, each with their different spoken languages and traditions, to ever truly understand one another. I thought my children’s grandparents would forever treat each other with the courtesy and distance brought on by the ocean that separated them. But, over the course of the last six months, our families would not only form a deep bond of mutual appreciation but find such joy in one another’s company. As my in-laws pushed my son in a stroller around our neighborhood, I was able to hear my own thoughts again and slowly find my way back to my writing.

What would we have done without this humble ADU? Our inconspicuous garage, on the corner of our small lot. Nowadays, I love looking at it as I pull into our driveway. I think of how gracefully it shouldered its many burdens, how it stood up to the challenge of all the things it needed to be, for all the people who belong to this family.

When my in-laws were finally able to return to Hong Kong, they could hardly bear to leave the babies. In our time together we celebrated four birthdays, weathered many bouts of illness, honored the passing of my grandmother and witnessed the emergence of my son’s first tooth. As I watched my in-laws pass the security checkpoint on the second floor of the international terminal, I recognized the extraordinary good fortune given to us by this time we had together. We had become the kind of multigenerational family that was a cornerstone of our ancestors. We had found a life I’d never imagined for myself in Los Angeles.

There used to be a time when all I wanted was to chase thrills as far away from family and home as possible. Now I just want to offer all of us a place to belong, a new way to be together.

Xuan Juliana Wang is the author of the story collection “Home Remedies.” She was born in Heilongjiang, China, and lives in Los Angeles.

More stories from Image