Lisa Boone is a features writer for the Los Angeles Times. Since 2003, she has covered home design, gardening, parenting, houseplants, even youth sports. She is a native of Los Angeles.

- Share via

1

The five-bedroom, two-bathroom house was advertised as “a charming fixer, traditional style home in the heart of Highland Park.”

In reality, it was legally uninhabitable because of multiple unpermitted additions over the years that resulted in substandard notices from the city and thousands of dollars in unpaid liens.

In 2014, the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety’s code enforcement cited the owners for an illegal garage conversion, which might explain why the house fell out of escrow multiple times, even in L.A.’s red-hot real estate market. Other flaws: The electrical wiring was not up to code. Nor was the plumbing. And the front door and porch had been illegally altered and were in violation of historic preservation overlay zone (HPOZ) standards.

Then there was the front room, which had been changed to include an arched wall that caused the floor to sink. Hundreds of dead cockroaches blanketed the sprawling layout.

Despite the red flags, architects Melissa and Amanda Shin of Shin Shin Architecture purchased the property in 2019 in hopes of realizing their professional work in a personal way: by creating a home for Amanda along with an accessory dwelling unit, or ADU, rental that would subsidize the renovation and add more housing to the neighborhood.

Situated in the Highland Park-Garvanza HPOZ in the Arroyo Seco, the house was not all cockroaches and code violations. It’s conveniently located across the street from a Metro L Line light-rail station and just steps from Figueroa Avenue’s many shops and restaurants. Most important, it fell within the Shins’ budget of $600,000.

“It was one big huge mess,” says Melissa, who has designed several ADUs with her sister. “But we wanted to play out the ADU model. We purchased the house largely for its location. Figueroa was a big draw for us.”

The 1923 structure was originally designed as a duplex, but it was reclassified as a single-family dwelling in the 1980s. After paying $654,500 for the roughly 1,600-square-foot house, the architects decided to do an about-face by implementing a surprising riff on backyard “granny flats.”

More stories about ADUs

They turned a one-car garage into a stunning ADU to house their parents. You can too

The L.A. ‘granny flat’ built for climate change: Take a look at the eco-chic inside

He challenged himself to build an ADU for under $100,000. What’s his secret?

She turned an unpermitted backyard studio into the ultimate WFH hideaway

How Los Angeles is bringing high design to the granny flat — while saving time and money

She built a granny flat in Echo Park: How it saved her during the pandemic

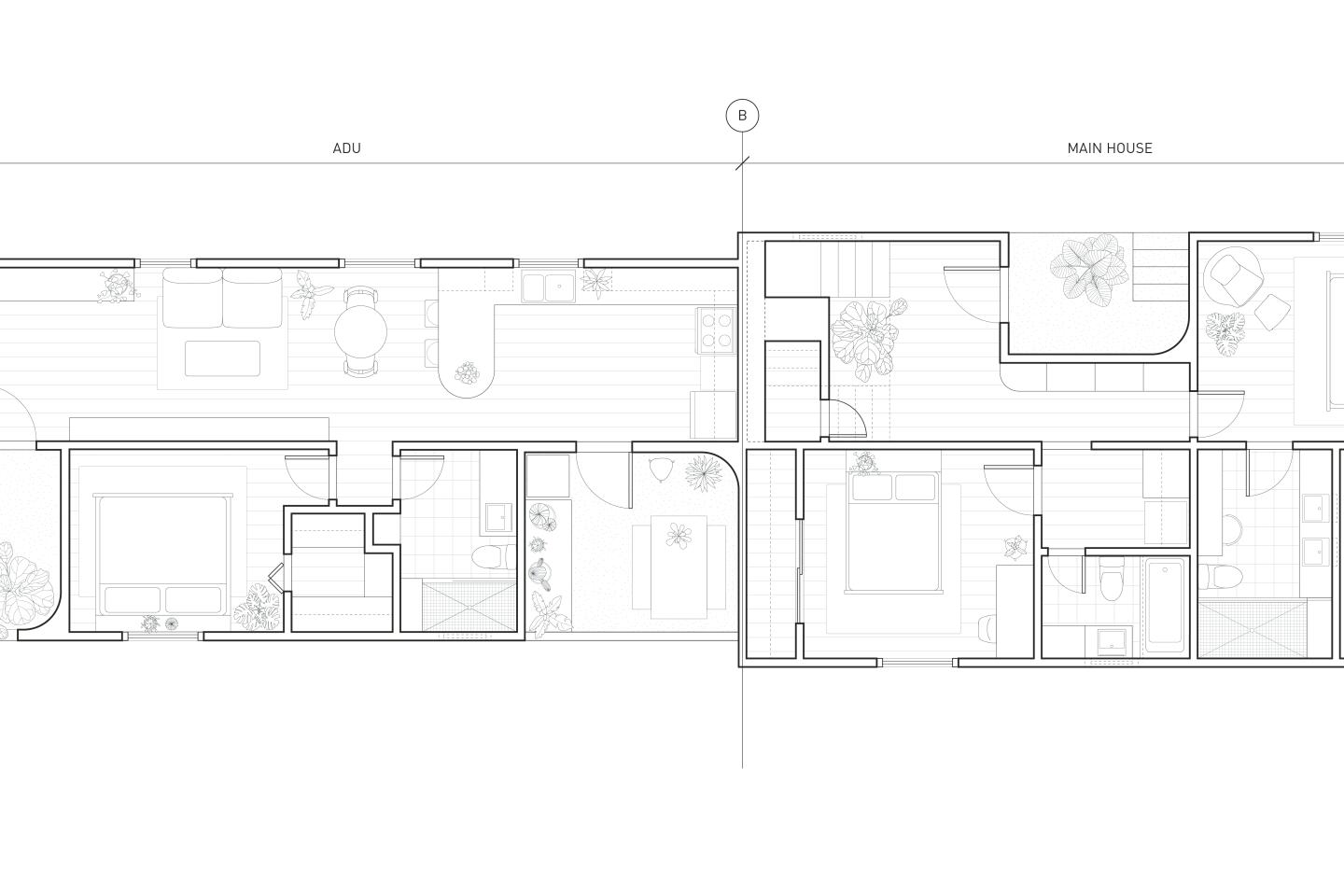

Instead of placing the ADU in the backyard, as is common, the architects decided to cut the building in two and convert the front into a 735-square foot, one-bedroom, one-bath unit and add a second story to the middle of the dwelling to create a 1,462-square-foot main house with two bedrooms and 2.5 baths in back.

The unique placement was inspired in part by regulations that require homeowners to “maintain and enhance the historic integrity, sense of place, and quality of life in the Highland Park-Garvanza HPOZ area.” They could not, for example, tear the house down or add on to the front. If they wanted to create a house for Amanda, they would have to add on to the back. (They also had to keep half of the original framing and the roof joists; after some back-and-forth, the historic board approved a partial arch on the porch that complemented other homes in the neighborhood).

As Los Angeles residents struggle to find housing in one of the least affordable markets in the country, architects like the Shins are experimenting with design by creating multifamily dwellings that help increase density. Popular and compact, ADUs are in demand thanks to new laws that make them easier to build (including a September law that permits up to two dwelling units on a single-family lot) and a preapproved standard plan that offers a simplified permitting process for the design and construction of ADUs.

A light-rail train passes across the street from the ADU.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

From the onset, the Detroit natives wanted to embrace the principles of classic Southern California indoor-outdoor living by creating exterior spaces in cost-effective ways. With this in mind, they added patios on separate axes for privacy — one in front of the ADU, which they affectionately call the “Mouse House,” and another on the second floor of the main house that faces the alley.

Growing up, Amanda, 33, was interested in art and architecture while Melissa, 36, was more science- and math-oriented. Design marries those interests. Melissa, who studied math at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, can’t resist describing the floorplan as a “process of subtraction and addition”: The house grows with the addition of 400 square feet of interior space and 570 square feet of semi-enclosed exterior space. Amanda, on the other hand, was more interested in vibe and temperature.

“A lot of our inspiration for the outdoor spaces comes from the fact that we both love plants,” Melissa says of the rubber plants, fiddle-leaf figs and monsteras that add drama to both of the sun-drenched homes. “All of Amanda’s plants were dying in her Koreatown apartment. But now they have lots of air and light.”

Working with a budget of $200,000, the pair designed the ADU with renters in mind. The bright, open, prefab kitchen includes an accessible breakfast bar. A vaulted ceiling softens the square lines of the long and narrow living room, and a large window brings in ample natural light. Knowing that pets are a priority for many renters, the two installed vinyl flooring throughout the ADU for durability. A flexible sunroom, which is enclosed with polycarbonate panels, extends the kitchen, adds further outdoor space and can be used as a laundry room, greenhouse or storage area. The bedroom’s small floorplan is somewhat misleading. The room accommodates a king-size bed, and the walk-in closet is big enough to house a dresser.

The rental features a prefab kitchen, Ikea pendants and pet-friendly vinyl flooring.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Keeping a close eye on numbers, the Shins pushed the design of the main house by using readily available materials such as standard plywood on the bookshelves and exposed oriented strand board on the exposed rafters.

“We wanted to spend money on things that would make a big difference,” Amanda says of the $6,000 Fleetwood sliding door — their biggest splurge — that opens to the patio and provides a wall of glass on the top floor.

On the ground floor, the Shins installed a master bedroom and bath, a laundry room and another walk-in closet that also serves as a sewing room for Amanda.

Up a stairway — designed as a place unto itself — and past a striking two-story plywood bookcase lined with art, books and personal mementos is the open living room and kitchen. The space is balanced by warm maple floors and exposed oriented strand board rafters, which serve as a counterpart to the plywood bookshelf below.

The living room of the main house is located behind the ADU, on the second floor.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Just off the kitchen is an expansive patio, complete with a barbecue and living and dining areas, that blends indoors and out, thanks to the custom Fleetwood slider. “You can claim your exterior space here in Los Angeles,” Melissa says. “You can only do that in a climate like this.”

A year after breaking ground on the renovation, the sisters listed the ADU for rent on Zillow. After they showed it to a crush of people, they quickly rented it to Anne Barkley, who says she walked into the unit and thought, “I must have this place.”

“You can tell that women designed these spaces,” she adds. Barkley rents the ADU for $3,000 a month and appreciates the many thoughtful touches throughout — the walk-in closet, the mirrored accents that maximize space, the “puffy” sage-colored kitchen tiles and geometric patterned concrete tiles in the bathroom.

“I was very specific about what I wanted,” she says of her struggle to find housing after renting in Mid-City. “It’s so disheartening when landlords don’t upgrade their rentals. People in Los Angeles will suffer without a garbage disposal or washer-dryer to have old-world charm.”

The kitchen opens to an outdoor patio.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Barkley likes the energy that comes from living across from the L Line station, which she can see from the large picture window in her living room. Amanda’s presence is also a plus — for both parties. Though Barkley rarely hears her landlord, despite sharing a wall, she likes knowing she is close by.

Amanda agrees. “Being a young, single female, I didn’t want to live alone,” she says. “We like the idea of shared spaces and creating microclimates that honor community values.”

In the end, the total cost (see a detailed list below) was approximately $600,000, or $273 per square foot, but the architects say a similar project today would cost around $400 to $500 per square foot because of supply chain and labor issues. “We started the plan check process in 2019 and ended in 2020, when it was still operating in person,” Melissa says. “It’s an entirely different world now.”

From the street, the modest bungalow keeps a low profile among the other vintage homes, while the second story is barely perceptible. What is exposed — a porch brightened by colorful peach stucco, a welcoming open patio and a garden planted with the architect’s own potted succulents — hints at the shared nature of the homes that rest behind the fence.

Is it possible, as Melissa suggests, that mathematics can help solve the housing crisis?

“What if everyone rented out a space to create more housing?” she puts forward. “We want to show that you can do a lot by focusing on big design moves. We should be sharing space if we’re going to tackle density.”

Architects Amanda and Melissa Shin enjoy the outdoor balcony.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

2

Budget

Note: Architect fees and permit costs are not included.