- Share via

I know the wind turbine blades aren’t going to kill me. At least, I’m pretty sure.

No matter how many times I watch the slender arms swoop down toward me — packing as much punch as 20 Ford F-150 pickup trucks — it’s hard to shake the feeling they’re going to knock me off my feet. They sweep within a few dozen feet of the ground before launching back toward the heavens, reaching nearly 500 feet above my head — higher than the highest redwood.

They’re eerily quiet, emitting only a low hum. But in the howling wind, the tips could be barreling past at 183 mph.

So yes, I’m a little terrified — but also full of awe. These machines are changing the world, after all.

More than 800 miles from Los Angeles — on ranchland littered with so much cow dung it’s hard not to step in it — the pastel-green hills are studded with wind giants. They dominate the scruffy sagebrush landscape, hundreds of them, framing the snow-streaked heights of Elk Mountain and casting dramatic shadows as gray clouds threaten to overtake a brilliant blue sky.

Before wind energy took off, there wasn’t much going on in this corner of Wyoming cattle country, says Laine Anderson, director of wind operations at PacifiCorp, the company owned by billionaire investor Warren Buffett that built these turbines.

“It was sagebrush and some hills, is basically all it was,” Anderson says. “A lot of ranchers out here trying to scratch out a living on what actually grows in the few months that we have a growing season. Winters out here can be pretty brutal.”

L.A. Times energy reporter Sammy Roth visits the construction site of America’s largest wind farm.

The American West is on the cusp of immense change. A region long defined by wide-open vistas is in the early stages of a clean energy boom that could fundamentally alter its look and feel. On your next Western road trip, watch for wind turbines in the backcountry. Drive through the desert and prepare for dark seas of shimmering solar panels.

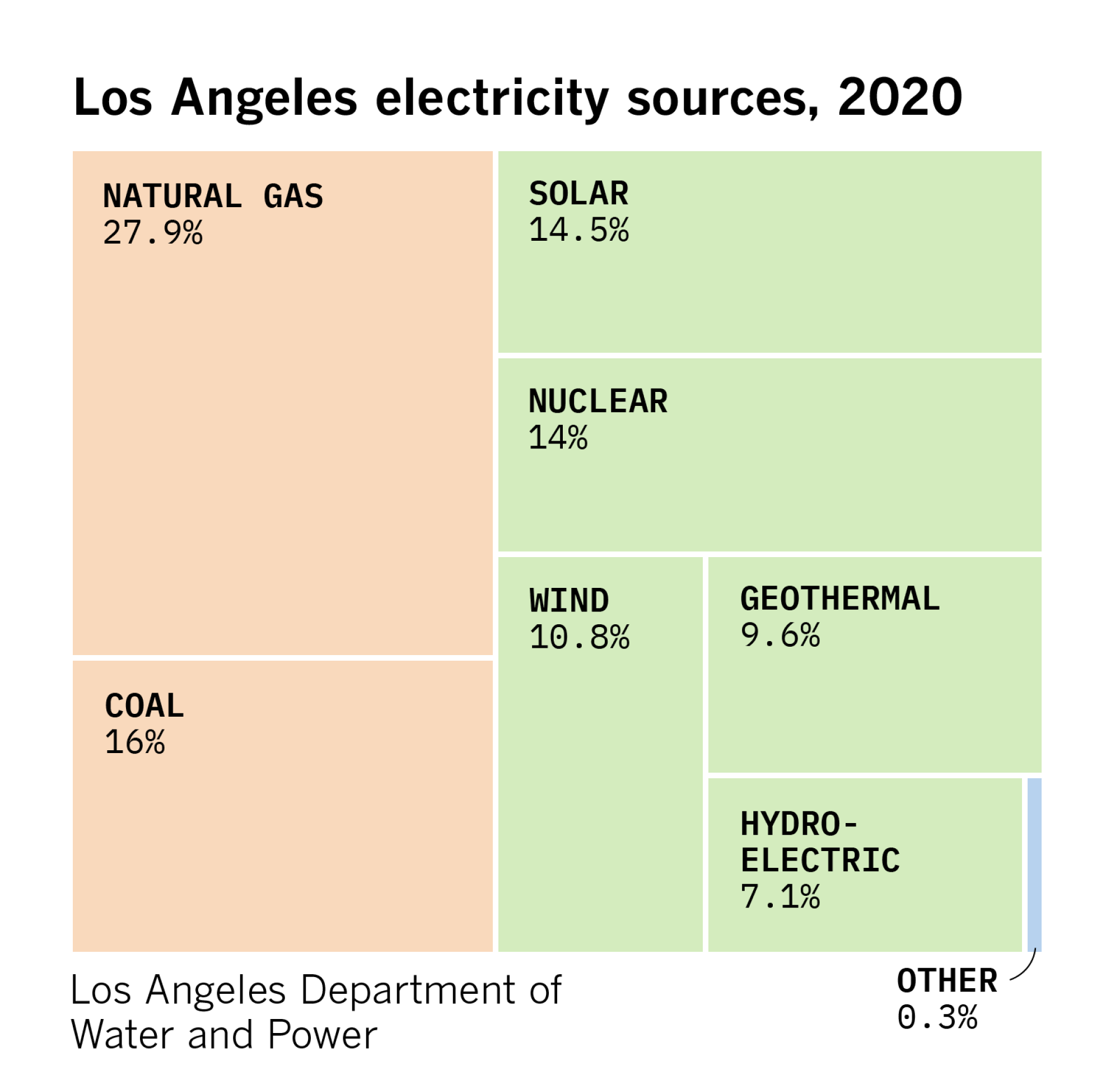

These renewable energy projects are cropping up across the rural West, driven largely by the power demands of distant cities: Los Angeles, Denver, Seattle and more. It’s not the first time those cities have looked far beyond their borders for electricity. They fueled their explosive 20th century growth by propping up coal plants and damming rivers, with little regard for the consequences.

The transition from fossil fuels to clean energy is desperately needed to confront the wildfires, droughts, heat storms and other deadly consequences of the climate crisis. The power-grid transformation will only get faster under a bill signed by President Biden this month, setting aside nearly $370 billion for climate and clean energy projects.

But renewable power is also reshaping landscapes, ecosystems and rural economies — and not always for the better.

Solar and wind farms can create jobs and tax revenues, reduce deadly air pollution and slow rising temperatures. But they can also disrupt wildlife habitat and destroy sacred Indigenous sites. Some small-town residents consider them industrial eyesores.

Those tensions have come to define Wyoming’s Carbon County — a place named for coal.

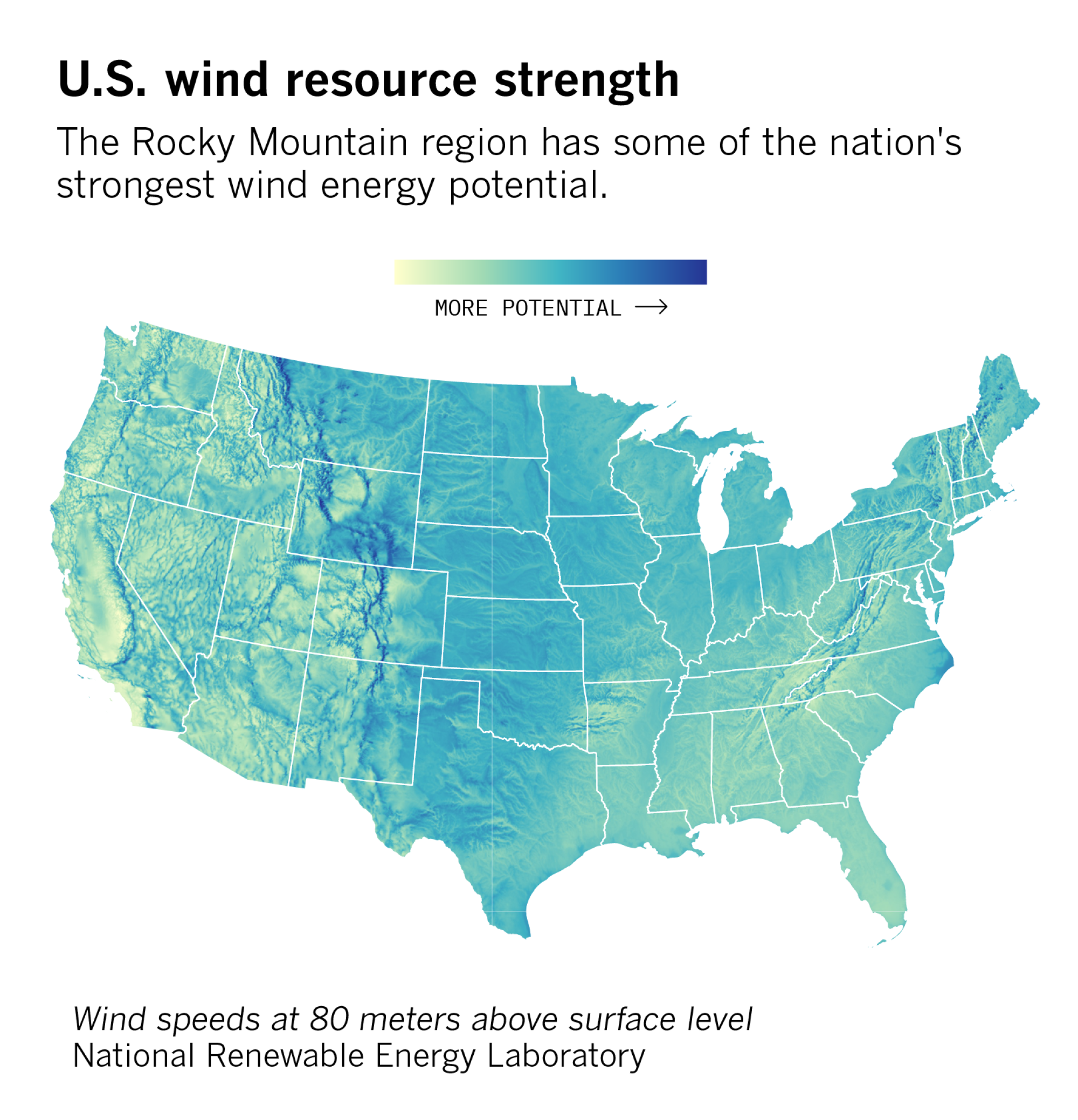

To understand why, look at a wind resource map of the United States. Most of the West is rendered in pale shades of green and light blue, meaning average wind speeds of 10 to 15 mph at best. But this part of southern Wyoming — where the Rocky Mountains drop down in elevation, creating a funnel-like effect — is streaked with thick veins of dark blue.

For wind energy developers, that’s the really good stuff: speeds of 20 mph and above.

Buffett isn’t the only ultra-wealthy investor looking to cash in.

Not far from the Oracle of Omaha’s clean energy kingdom, the reclusive billionaire Phil Anschutz — who owns the Coachella music festival, the Los Angeles Kings hockey team and L.A.’s Crypto.com Arena — is preparing to build the nation’s largest wind farm.

After nearly 15 years of planning, crews are constructing gravel roads. Pads are being cleared for roughly 600 turbines.

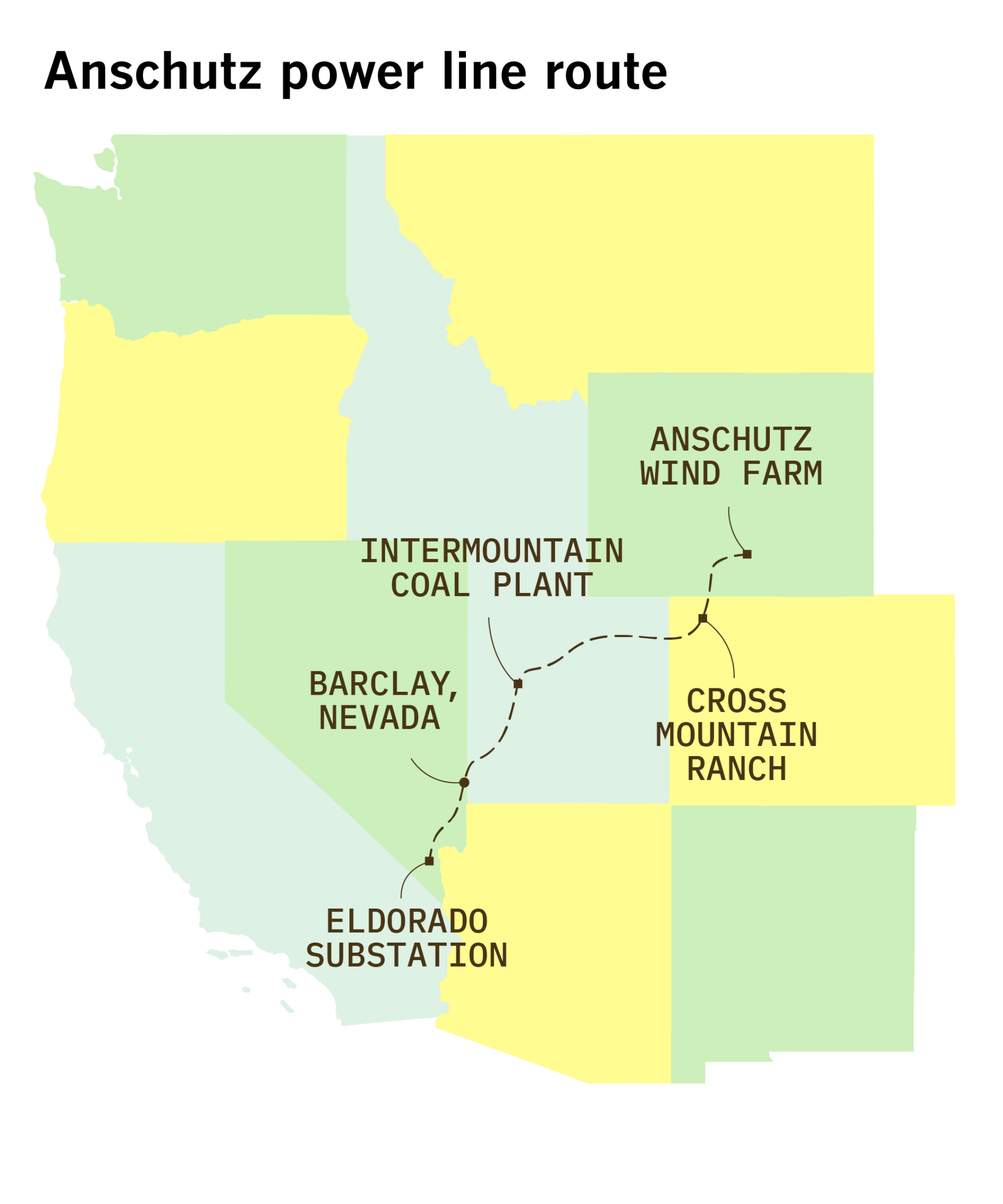

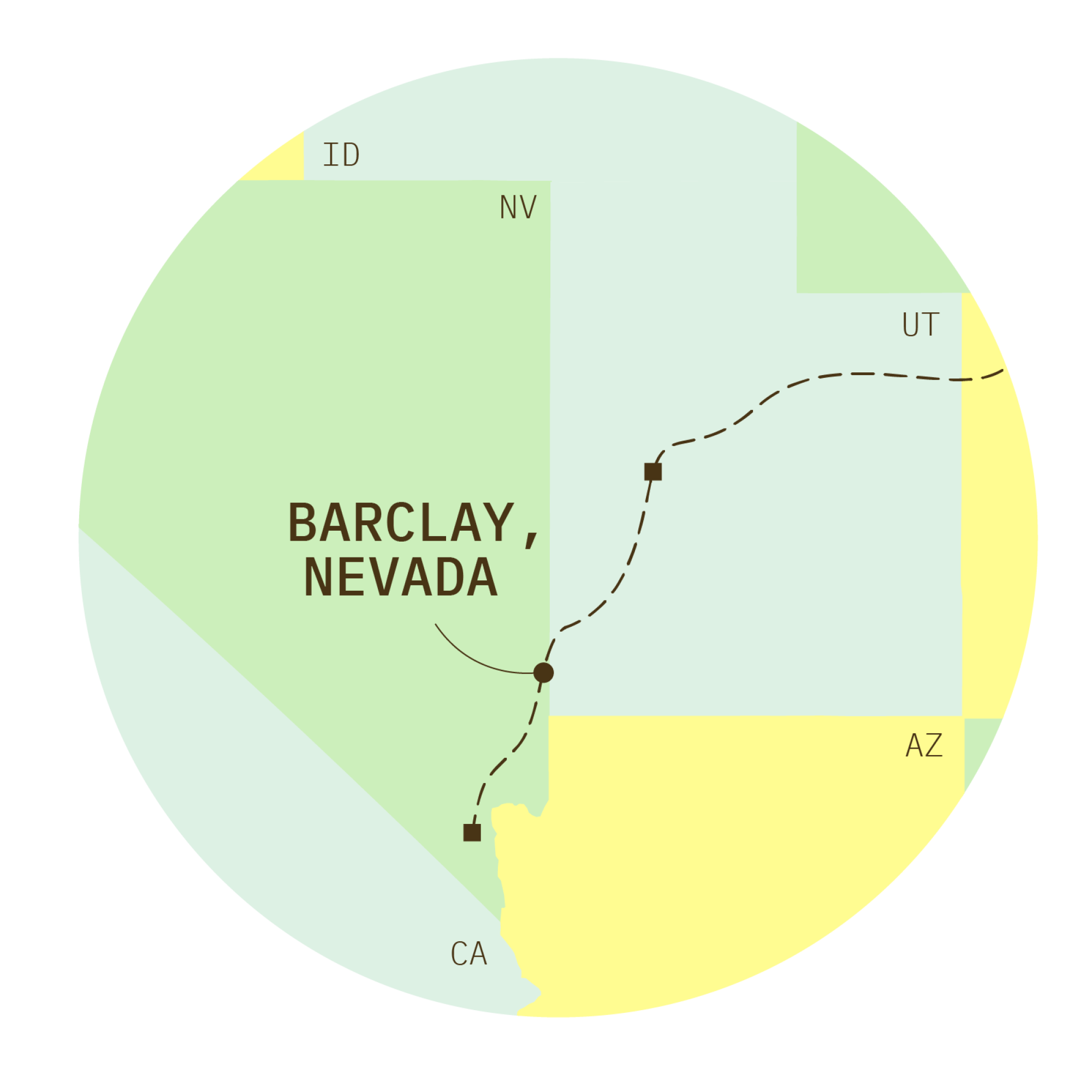

Wyoming’s half-million residents don’t need all that energy. California’s 40 million residents do. So Anschutz is getting ready to construct a 732-mile power line across Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and Nevada, to ship electricity to the Golden State.

It’s an audacious plan — and a harbinger of what’s coming for communities across the West.

To see what the future might look like, Los Angeles Times journalists visited Anschutz’s sprawling wind farm construction site, then traveled the planned route of his electric line. We talked with the project’s fiercest supporters and harshest critics.

Along the way, we came to realize the West’s great cities have a choice. They can open themselves up to hard conversations with small-town residents, ranchers, Native American tribes and wildlife advocates, and do their best to find common ground. Or they can try to steamroll whoever gets in their way.

Neither option is guaranteed to speed the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy. The stakes are high. Time is short.

The ranch at the top of the world

Shards of red-and-brown sandstone grind beneath Bill Miller’s boots as he steps out of a pickup truck and gazes across the vast sagebrush expanse, home to pronghorn and golden eagles. He points out the landmarks: the jutting cliffs of the Atlantic Rim, the wagon route once traveled by white settlers, the mountain pass named for legendary wilderness guide Jim Bridger.

The 75-year-old knows this land better than anyone — including his boss, Anschutz, who has run cattle here for a quarter-century.

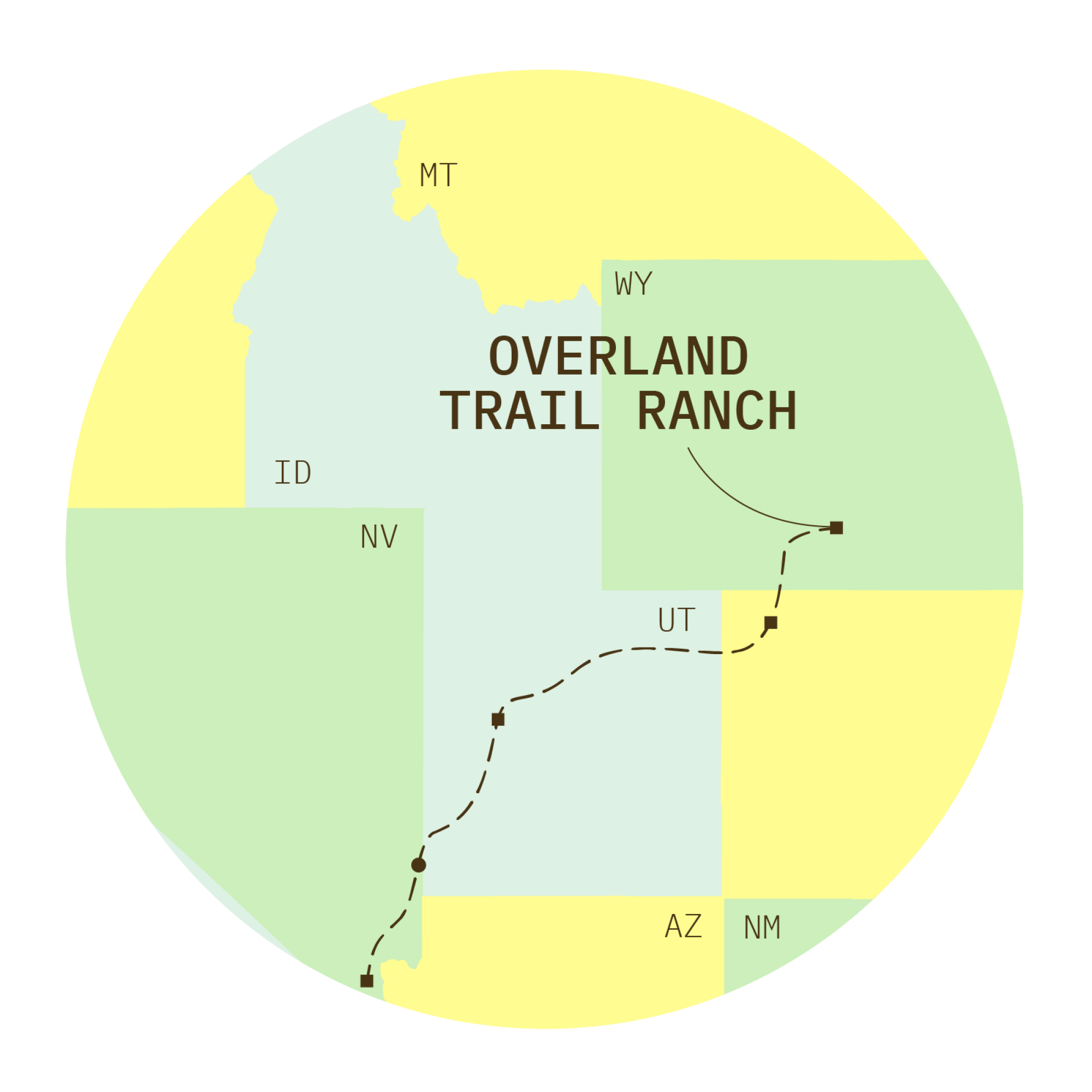

Overland Trail Ranch straddles the Continental Divide, an invisible line through the Rockies that slices the United States in two. On one side, rain and melting snow flow east to the Gulf of Mexico. On the other side, those waters flow west, coursing through the Colorado River and its tributaries before getting siphoned away by farms and cities, including Los Angeles.

The snow on the horizon marks Miller Hill — not named for Bill, he assures us. It has some of the ranch’s best winds, with average speeds of 25 mph and capacity factors pushing 60% — meaning in a typical year, the turbines’ total output should be almost 60% of the power they could have produced if operated at full capacity 24/7.

“The wind comes up in the morning and blows like hell until the middle of the night,” Miller says later, as he drives a rugged dirt road up Miller Hill. “The shoulder hours in the evening, or even in the morning when people are turning on the coffee pot — that’s the most highly productive time of day for us. Especially those evening shoulder hours when solar just goes off.”

In other words, this place isn’t just windy — it’s windy at exactly the time of day when California has had trouble keeping the lights on. That means hot summer evenings, when solar panels stop producing but people still need air conditioning.

As we make our way up Miller Hill, we spot several packs of pronghorn, commonly called antelope, easy to identify by the white patches on their butts. They’re North America’s fastest land mammal, and Overland Trail Ranch gives them plenty of room to run. At 500 square miles, it’s slightly larger than the city of Los Angeles.

Because of the West’s checkerboard land pattern, Anschutz owns only about half of the ranch’s 320,000 acres. The rest belongs to the American public. He leases those lands for cattle grazing, and they’ll be part of his wind farm too.

The 82-year-old conservative mega-donor made his initial fortune drilling for fossil fuels, and he’s rarely spoken publicly about his views on climate change. He told Forbes magazine in 2019 that although he believes heat-trapping carbon dioxide “is a problem,” it’s “not as extreme as some would think.” His team declined my interview requests for this story.

But Miller, who talks with Anschutz most mornings, doesn’t mince words on climate. As his truck jostles on the bumpy road up the hill, he describes the strips of early-May snowpack still coating nearby slopes as the dregs of a poor winter. The lack of precipitation in the Rockies the last few years, he says, “has been pretty startling.”

“I’ve seen it firsthand. Then of course you read about it in the paper, practically every day,” he says. “Look at what’s happening with Lake Powell, Lake Mead, all the other surface water sources throughout the West.”

Climate change is “happening in real time, right in front of us,” he says.

Miller has worked for Anschutz for 42 years, overseeing the billionaire’s oil and gas operations for many of them. He’s not wrong when he says it would be impossible to phase out fossil fuels overnight. But he knows the transition is underway.

“People holler and scream and bitch and bellyache about it, but at the end of the day, it’s happening. Society has spoken. They know what they want. And we’d better listen,” he says.

As symbolism goes, it’s hard to improve on the Anschutz Exploration Corp. flag affixed to a wall in one of the trailers serving as construction headquarters. It features the outline of an oil rig — only someone has affixed three oval strips of paper to the top, transforming the rig into a makeshift wind turbine.

But here’s the tricky part, for Anschutz and many companies developing renewable energy.

Most of the 100% clean electricity deadlines set by cities and states are still a decade or two away. And as cheap as solar and wind energy have gotten — especially relative to the climate damage society is already suffering — they still need to be paid for, with homes and businesses footing the bill. Politicians have only so much appetite for so much renewable power, so fast.

For all the world-class wind at his fingertips, even Anschutz hasn’t yet found a buyer — and not for lack of trying.

A dozen years ago — when wind power was far more expensive — Anschutz personally attempted to negotiate a deal with Los Angeles officials, according to then-Deputy Mayor S. David Freeman. But the billionaire kept demanding “more money than I thought was appropriate,” Freeman told me before he died in 2020. City officials also considered buying the ranch outright.

Anschutz’s asking price for wind energy has almost certainly dropped. But his ideal buyer hasn’t changed.

“Los Angeles Department of Water and Power would be a very natural customer,” Miller says.

When we finally reach the top of Miller Hill, the view is spectacular — endless rolling hills, occasional patches of snow and hazy blue mountains fading into the horizon. I try to imagine a not-so-apocalyptic future when I’m able to stay cool and safe during a sweltering heat wave back home in L.A., and this ranch is part of the reason why.

Saving the sagebrush sea

Money isn’t the only barrier to a wind-powered future. You’ve got to consider the sage grouse.

Just ask Erik Molvar, executive director of the Western Watersheds Project. He’s part of a robust environmental resistance that has sprung up to fight many large solar and wind farms, arguing they destroy wildlife habitat and are far from eco-friendly.

“We probably shouldn’t be building utility-scale renewables projects on public lands at all,” Molvar says.

Overland Trail Ranch is covered in a delicate sheet of snow from a storm the night before as Molvar leads us on his own tour. We don’t see any sage grouse — they’re nearly as reclusive as Anschutz. But as we pull over on the side of Highway 71, Molvar spots a pack of elk in the distance, trotting away from us. He suspects they caught our scent.

“They’re adapted for smelling their natural predators, and humans are their predators,” the wildlife biologist says.

Molvar is no climate obstructionist, at least not in his view. Like many conservationists who spend their lives tracking birds and beasts, he wants to see Los Angeles and other cities blanketed with solar panels — on rooftops, warehouses and parking lots — before paving ecosystems for solar and wind. He says climate change is urgent, but no excuse to sacrifice wildlands.

“We can’t afford to squander our opportunity to save the little fragments of wildness that we have left,” he says.

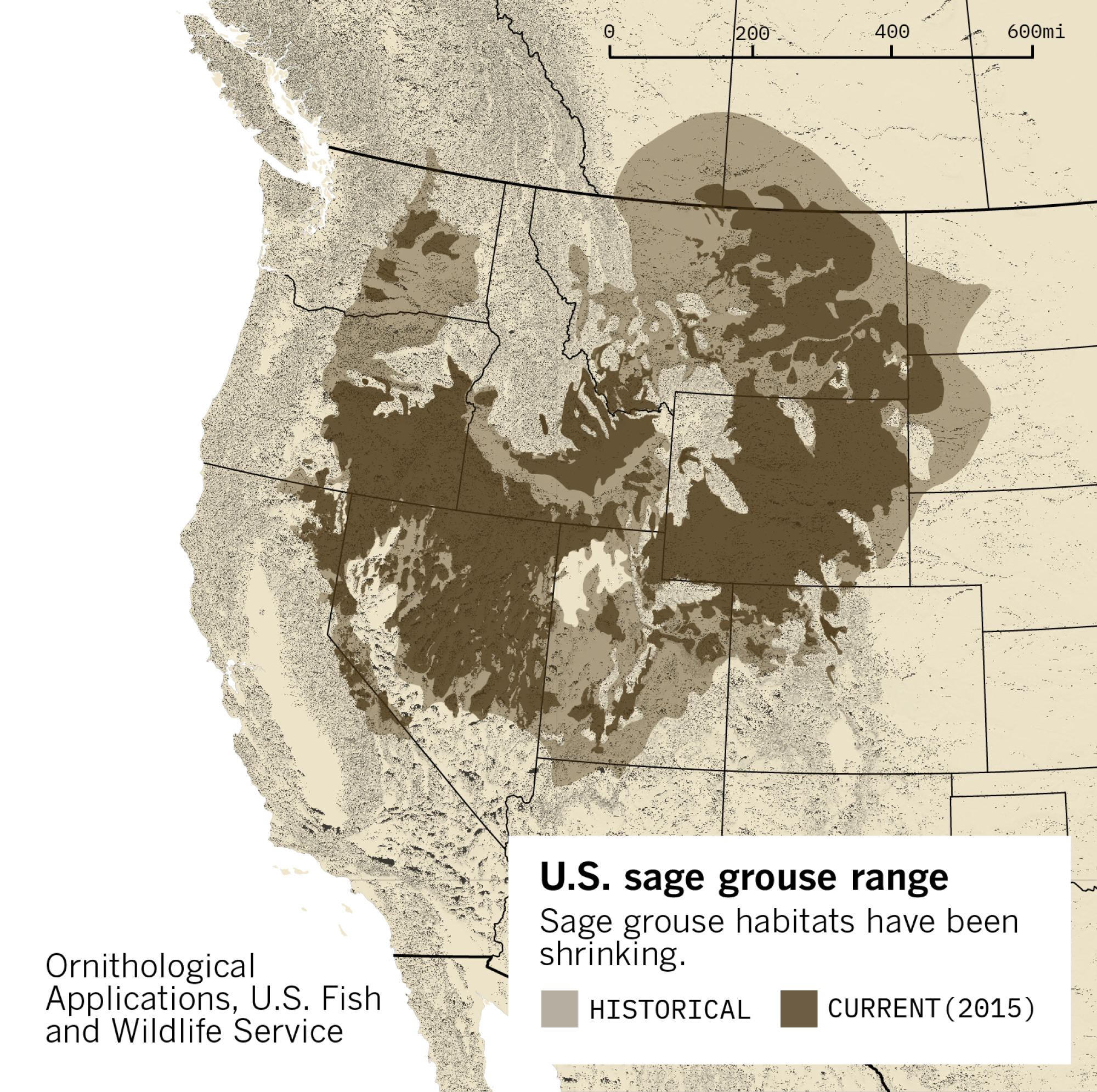

It’s an argument that has thrust the greater sage grouse into the national consciousness.

The Western bird is famous for a mating dance in which males puff out their chests and swagger around breeding grounds called leks. But grouse populations are in free-fall, making them a poster bird for the extinction crisis — and a political lightning rod.

Scientists say grouse can’t afford to lose much more ground. Farms, ranches, subdivisions, wildfires and oil and gas drilling have already destroyed or degraded much of the West’s “sagebrush sea,” defined by an unassuming yellow-flowered shrub.

And if grouse are struggling, it’s a sign that other creatures are probably in trouble too.

“Sage grouse is the bellwether,” Molvar says. “If you save the sagebrush ecosystem at a level that will accommodate sage grouse, then you will also be providing adequate habitat for scores if not hundreds of other species.”

As we sit on the side of the highway, Molvar pulls up a map on his laptop, showing parts of Wyoming that a state task force once recommended as “core habitat” for the bird — including three-quarters of Overland Trail Ranch. But officials ultimately chose not to designate many of those areas as core habitat, the map shows — clearing the way for Anschutz’s wind machines.

What changed? Bob Budd, who leads the Wyoming sage grouse task force, says it wasn’t the science. Instead, he says, Anschutz’s company successfully pushed back, arguing it had an existing legal right to build a wind farm.

Anschutz officials tell a different story. They say extensive sagebrush mapping by one of their consultants found that much of the proposed habitat was actually lousy for sage grouse — while other areas where the company hoped to build were better spots for the bird.

Wyoming ultimately designated 91,000 acres — more than one-quarter of the ranch — as core habitat.

“We ended up having to give up some of the best winds on the ranch,” Anschutz executive Roxane Perruso says.

Golden eagles were another concern.

Federal officials estimated the 1,000 wind turbines initially planned by Anschutz could kill 46 to 64 golden eagles a year, although they noted that conservation measures would probably result in fewer deaths. They later downgraded their estimate to 10 to 14 birds killed or harmed by the first 500 turbines.

According to the Bureau of Land Management, the wind project could actually be a “net benefit” to the species because Anschutz agreed to fund projects elsewhere in Wyoming to reduce eagle deaths.

Miller says his team studied eagle flight patterns and tracked sage grouse movements across the ranch, resulting in several project redesigns. In areas disturbed by construction, workers are replacing topsoil and replanting native vegetation.

“There will probably be some impact on virtually every species,” Miller acknowledges. “But at the end of the day, the actual ground disturbance — not the entire footprint, but the actual ground disturbance — is, I believe, about 1,700 acres.”

When asked about that idea — that the actual land area taken up by wind turbines will be small compared with the overall project site — Molvar laughs. He calls it a modified oil and gas industry talking point that ignores scientific reality.

Here’s the thing, though: Good science can get you only so far in this debate. There are value judgments at work.

For many environmentalists, fighting climate change is the top priority. They want to see renewable power plants built as fast as possible, to prevent wildfires and droughts and floods from getting out of control — even if some habitat gets destroyed.

There’s middle ground, because of course there is. Although studies show that slowing global warming will require a mind-boggling number of wind and solar farms, they also see a huge role for rooftop solar. And environmentalists across the spectrum — Molvar included — view farmland as a prime spot for big solar projects, especially in places where water supplies are drying up.

But compromise is hard. And meanwhile the planet keeps warming.

Clean energy activists and utility giants are duking it out over the future of rooftop solar.

Brian Rutledge, a former vice president at the National Audubon Society, knows how difficult it is to find consensus. He owns a ranch in northern Colorado, near the Wyoming state line, and he pushed the Anschutz team to redesign its project to limit bird deaths. He’s also deeply familiar with Audubon research showing global warming could wipe out hundreds of bird species.

Rutledge says the Anschutz team “worked probably harder than anyone I’ve ever worked with in the wind energy industry to try to do things right.” But when I ask him for his overall view of the clean power project, he sounds conflicted.

“Overall it’s good people trying to do right,” he says. “But that doesn’t change the footprint, doesn’t change the impacts.”

It also doesn’t change the climate reality. The Audubon Society estimates sage grouse could lose 77% of their current range — including most of Wyoming — with just 2 degrees Celsius of planetary warming. We’re on pace for far worse.

Threading the needle at Cross Mountain

Nobody would dare stick wind turbines or solar farms on the rims of the Grand Canyon, or on the floor of Yosemite Valley. National parks and wilderness are the West’s sacred spaces, protected by law and culture and an unmistakable aura of mystique.

Farms and ranchland are another story. To city slickers, they might seem like the perfect places to put renewable energy — sun-swept fields and windy plains degraded by pesticide use and overgrazing, practically crying out for a second economic life.

But there are two problems.

First, many rural Westerners see clean energy infrastructure as a threat to the lifestyles and mythologies they hold dear — at least in part because they associate it with Blue America and the Green New Deal. And second, plenty of farms and ranches are owned by wealthy investors — people with the time and money to fight renewable energy projects they don’t like.

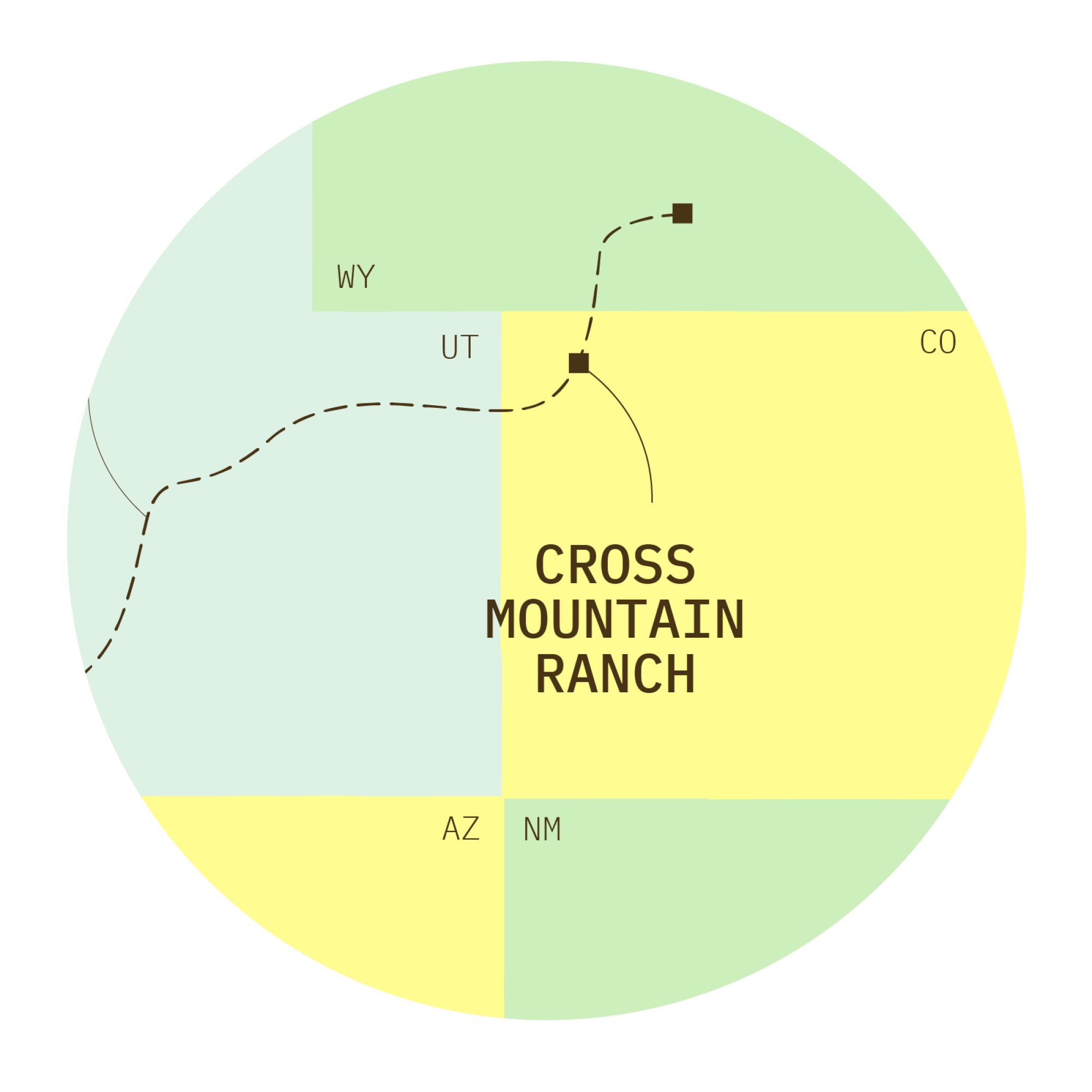

All of which brings us to Cross Mountain Ranch.

One hundred miles southwest of Anschutz’s wind farm site, the sparkling Yampa River meanders through fields of sagebrush greener and more lush than anything we saw in Wyoming. A few miles downstream, its waters join with the Little Snake River, carrying Rocky Mountain snowmelt to farmlands outside Phoenix and the Bellagio’s dancing fountains in Las Vegas.

Cross Mountain is owned by the family of the late Ronald Boeddeker, the real estate mogul who built Lake Las Vegas. Anschutz was adamant his power line would run through the Boeddeker ranch — triggering a clash of titans that illustrates perhaps the greatest obstacle to building enough renewable energy to survive the climate crisis.

Simply put: It’s easy for opponents to gum up the works.

Our Cross Mountain tour guide, Erik Glenn, drives us to a high point overlooking the Yampa. This is where Anschutz wants his TransWest Express electric line to cross the river, alongside another line planned by Buffett’s PacifiCorp.

Alfalfa grows along the banks. Glenn calls this area “one of the most biologically significant parts” of northwest Colorado.

“In the West, wherever you’ve got water, you’re going to have a lot of biodiversity,” he says.

The organization Glenn leads, the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust, helped line up millions of dollars in federal, state and private funds to purchase a “conservation easement” on 16,000 acres of the ranch. In exchange for that money — plus a tax break — the Boeddekers promised to keep those acres rural in perpetuity. No subdivisions, no energy projects.

Which is how the Boeddekers became the last holdout on Anschutz’s 732-mile route.

Along with Ronald Boeddeker’s son Matt, who lives in California, Glenn pressed the federal agency that helped fund the easement to block Anschutz’s and Buffett’s power lines. The billionaires responded by suing the feds, the land trust and the Boeddekers.

With electric wires crossing through, “this landscape is going to look dramatically different,” Glenn says.

But the two power lines should take up just 30 acres of the 16,000-acre conservation zone. Would that really be so much to ask of the Boeddekers, and of the local flora and fauna? Especially given the climate benefits?

Pressed on that point, Glenn brings up the “30 by 30” campaign — an effort to protect 30% of all lands and waters in the United States by 2030, with a goal of safeguarding wildlife from rising temperatures and human encroachment.

Climate change spurred Friday’s unanimous vote by the Los Angeles City Council.

“We want more renewable energy, and we want more conservation. And those two things are going to collide,” Glenn says. “I don’t envy TransWest, I don’t envy PacifiCorp. I don’t envy any of these companies trying to figure out how to site these projects.”

Glenn eventually allows that electric lines are “somewhat compatible” with conservation, and that it might make sense to allow them on future easements. It’s one of many small changes he thinks could help clean energy projects move forward.

“You’ve got to thread the needle,” he says.

Here’s the problem: Almost anywhere you try to build renewable energy in the West, you’ll face opposition. Whether it’s based on protecting wildlife, preserving scenic views or promoting fossil fuels, someone will come forward and fight to maintain the status quo. Threading the needle means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Take the Boeddekers: Glenn says it was “devastating” for them to imagine power lines crossing the Yampa River at one of the prettiest spots on their ranch. He suggests a more suitable crossing point for Anschutz and Buffett would have been a piece of public land just downstream — near the put-in for rafters beginning a spectacular trip through Cross Mountain Gorge.

“For a private landowner, they want to see that happen on public lands, if it’s a public project,” Glenn says.

These power lines aren’t public projects, though. Sure, they were approved by the federal government, and they’re responding to a public desire for clean energy. But they’re very much for-profit enterprises that will enrich their powerful backers.

Anschutz and Buffett eventually worked out a deal with the Boeddekers. Although none of them would disclose the financial terms, Anschutz had previously offered a one-time payment of $24,000 to cross the ranch, which his company says was “based on an appraisal report of the property and included a 25% premium.” It’s safe to say his final offer was higher.

Anschutz expects to start building TransWest next year. By the time his power line and wind farm — known as Chokecherry and Sierra Madre — start coming online in 2026, the company will have been working on them for nearly two decades.

That’s no recipe for speeding up the clean energy revolution and stemming the climate crisis.

Standing on the train tracks

The Boeddeker family was just one of many hurdles for TransWest Express. The federal government’s environmental review and approval process took more than eight years. Anschutz’s team also had to secure permits from 14 counties and two states — and negotiate deals with more than 450 private landowners along the route, all of whom received one-time payments.

Not far from Cross Mountain, officials at Dinosaur National Monument have raised their own concerns. Anschutz’s and Buffett’s power lines will cross an isolated two-lane road leading to the monument — and the National Park Service isn’t thrilled.

“It is a rural, scenic road with panoramas free of modern intrusions,” the monument’s superintendent, Paul Scolari, says in an email. “The two transmission lines will introduce a note of dissonance into the natural, rural, panoramic scene.”

It’s easy to sympathize with the National Park Service’s desire for natural, rural scenery. At the same time, they’re talking about a paved road branching off a transcontinental highway — a modern intrusion if ever there was one.

The reality is, change is deeply embedded in the modern West.

First it was white settlers such as Jim Bridger, carving paths that would be followed by gold-seekers, Wells Fargo wagons and Mormon migrants. Then came the railroad, which was built through Carbon County for the same reason it’s a wind energy hot spot today — the low point in the Rockies. Indigenous peoples were torn from their homelands — and often slaughtered — to make way for ranches, farm empires, coal plants, oil fields and still-growing megacities. The landscape was left deeply scarred.

We saw some of those scars on our road trip: the Craig coal plant smokestacks spewing fumes over northwest Colorado, the unnaturally still waters below Flaming Gorge Dam on the Green River, the hotel-casinos of the Las Vegas Strip.

But much of the worst damage is elsewhere. It’s on the Navajo Nation, where the uranium industry poisoned groundwater with radioactive waste. It’s at Glen Canyon, a red-rock cathedral inundated by Lake Powell. It’s in the California oil patch, where toxic chemicals sicken low-income families.

Solar and wind farms are only the latest force to reshape the West. And they’re far less destructive than fossil fuels.

But that doesn’t mean much to rural Westerners who feel they’re on the losing end of the clean energy transition — especially now that the transition needs to accelerate, to catch up with the rapid heating of the planet. In every Western state, there are small-town residents fighting clean power projects.

So it’s all the more striking to see Rawlins — the Wyoming town nearest Anschutz’s ranch — embracing clean energy.

When wind energy developers first swarmed Carbon County, “that just scared us to no end,” says Rawlins Mayor Terry Weickum, sitting in the otherwise-empty City Council chambers. Would wind turbines ruin the wide-open views? What would they mean for fossil fuel jobs, which had already been disappearing for decades?

But Weickum did his homework and surveyed the economic reality. Eventually, he and other local leaders concluded wind energy could be a valuable source of property taxes and other revenue. He helped rewrite state policies, ending a sales tax exemption for wind companies and establishing a production tax of $1 per megawatt-hour.

In late 2020, during the economic depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, three Wyoming counties saw big jumps in taxable sales: Carbon, Albany and Laramie, all of them thanks to wind projects.

“There’s nothing political about it,” Weickum says. “They’re a chunk of metal, and they’re fiberglass.”

That reality hasn’t taken hold for a handful of state lawmakers, who keep trying to create roadblocks for wind. But locally, attitudes are changing. When Carbon County adopted a new seal last year, it picked a design with an oil rig and a wind turbine.

Accepting change goes against human instinct. But Weickum knows change is inevitable. His town was founded in the 1860s to support the transcontinental railroad — a crowning achievement that before long was largely displaced by automobiles.

“You can stand in the middle of the track. Or you can stand at the switch and decide where the train goes,” Weickum says.

And if you’re going to hitch your wagon to a new economic engine, renewable energy isn’t a bad bet.

Wind turbines and solar panels generated 12% of U.S. electricity in 2021, federal data show — double their share five years earlier, and poised for even faster growth. In Carbon County, Buffett’s PacifiCorp is going big on repowering — tearing down old turbines and replacing them with newer models capable of producing far more electricity.

Anschutz is so confident he’ll be able to sell clean electricity that he’s spent more than $400 million permitting and preparing to build his wind farm and power line, out of an expected $8-billion price tag — even without a customer lined up.

Those investments are no act of corporate do-goodery. Anschutz and Buffett intend to make boatloads of money.

But for urban activists and elected officials hoping to slow the climate crisis, the economic self-interest of wealthy investors is no guarantee of success. If they want to get solar and wind farms built faster, they’ll probably need to work with the communities on the front lines of the energy transition — and figure out how to make them partners instead of adversaries.

The last outpost of Los Angeles

The giant coal pile behind Intermountain Power Plant is smoking. The plant’s spokesperson, John Ward, assures us it’s normal.

“That’s called spontaneous combustion,” he says. “They’ll snuff it out here shortly.”

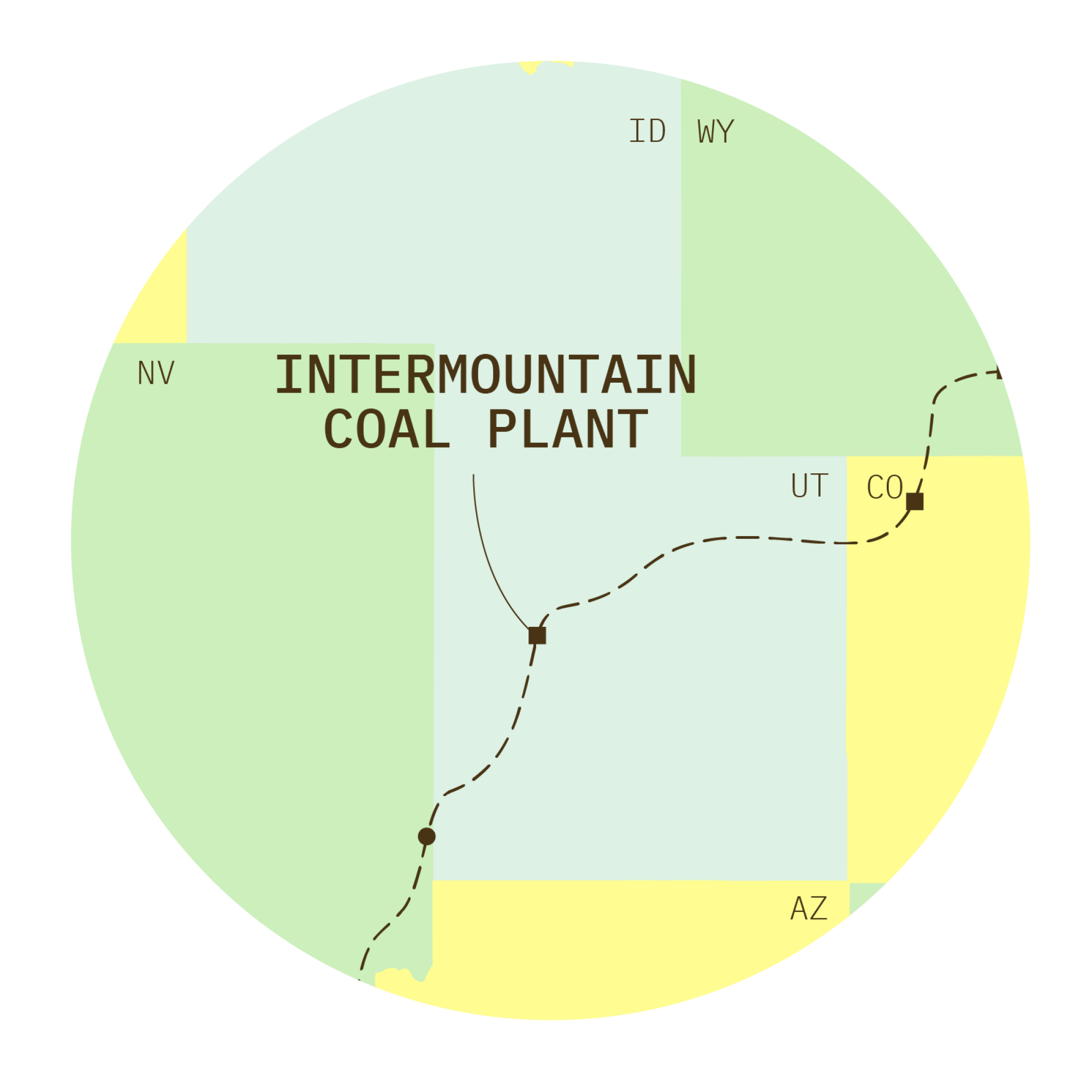

This Utah coal station is the largest power source for Los Angeles, 500 miles away. Anschutz’s electric line could help replace that power — with long-lasting consequences for the nearby town that’s helped fuel the West’s biggest city for decades.

L.A.’s decision to build Intermountain Power Plant in the 1980s reshaped Delta, Utah, reviving an economy that locals say never really recovered from the Great Depression. Intermountain employed more than 400 people at its peak, with many jobs paying six-figure salaries. The local school district has state-of-the-art classrooms, gyms and other facilities, thanks largely to coal.

Now Los Angeles is changing course, targeting 100% clean electricity by 2035. And Delta has no choice but to change with it.

As we stand on an outdoor platform atop one of the coal generators — a 710-foot smokestack towering overhead — Ward points to the open dirt where the L.A. Department of Water and Power is preparing to build a new power plant. It’ll initially run on a mix of 70% fossil natural gas and 30% green hydrogen, before ramping up to 100% green hydrogen. Nothing like it has ever been attempted.

Ward also points across the street, where natural salt domes, thousands of feet below ground, provide a perfect venue for storing hydrogen. Magnum Development and Mitsubishi Power have secured more than $1 billion in financing to carve out underground caverns where Los Angeles and others can bank the fuel for months at a time. The companies plan to install “electrolyzers” for converting water to hydrogen, powered by wind and solar energy during times of day when it might otherwise go to waste.

We drive across the street to the salt cavern site, where the only activity is a truck applying water to keep down dust. That doesn’t diminish Ward’s enthusiasm. He believes Delta is on the ground floor of something big.

“This could become a hub for electrolyzer manufacturing and assembly,” he says.

Anschutz wants in on the action.

It’s long been his plan to route TransWest Express through Delta — in part to give him the option of shipping wind energy the rest of the way to Los Angeles via the Department of Water and Power’s existing transmission line, should the city choose to buy some of that energy.

Now L.A.’s green hydrogen plans offer another opportunity. Anschutz could supply some of the power that converts water to hydrogen. Or his company could produce hydrogen at Overland Trail Ranch and ship it by rail.

Hydrogen “really wasn’t even in our conversation until about a year ago,” Miller says.

But as solar and wind replace fossil fuels, electric companies will need more and more clean power sources that can keep the lights on when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. The Anschutz team is increasingly confident about the green hydrogen market.

“We’ve had a long-standing dialogue with LADWP,” Miller says.

A DWP spokesperson declined to comment, saying any hydrogen or wind energy negotiations with Anschutz are covered by a nondisclosure agreement. But there’s a natural fit. In a recent study laying out L.A.’s options for reaching 100% clean electricity, researchers from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory included Wyoming wind in every scenario they considered.

From a public health standpoint, the coal plant’s planned 2025 closure is good news for Delta too. Intermountain spews loads of lung-scarring nitrogen oxides, a component of smog. It also produced more than 6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2020, federal data show — making it the eighth-largest climate polluter among Western power plants.

By shutting down Intermountain, Los Angeles is righting a historical wrong — as are cities ditching coal across the West.

They’re also taking a blunt knife to rural economies. In Delta, property tax revenues may go up when the new plant opens — the coal generators have depreciated over the years — but staffing is expected to be well below today’s levels, at about 120 employees. Nearby wind and solar development could create thousands of construction jobs. But those are temporary.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

And yet: Even as Utah lawmakers lash out against L.A.’s hydrogen conversion, Ward says the local governments that share in the coal plant’s riches have figured out how to make the best of a less-than-ideal situation. They’ve realized that without Los Angeles, they’d have no customer, and all the jobs and taxes would go away. Like Carbon County, they’re listening to the market.

“The Utah partners could have said, ‘2025, we’re done, we’re walking away from here,’” Ward tells us. “But because they wanted to keep something going in this part of the world, they did the brain damage to put this project together.”

Asking rural communities to put themselves through “brain damage” to help solve a global crisis isn’t especially fair. But climate change isn’t fair. This late in the game, solutions that do no harm are exceedingly rare.

The end of the line

Brent Hafen spends most of his time on the ranch these days, living in the house his great-grandparents built in 1890, the house where his grandmother was born. It’s one of a handful of homes in Barclay, a tiny Nevada town 100 miles outside Las Vegas. Hafen and his wife fixed up the place themselves, not long after they restored the schoolhouse his great-great grandfather built.

It’s been six years since Hafen took over the ranch for his dad, now 95. He’s eager to show us around — and share his anxieties about Anschutz’s power line, which will skirt the edges of his land.

Wearing a cowboy hat and a gleaming belt buckle he won in a rodeo-like ranch sorting horseback competition in Texas, he loads us into his pickup and takes us out to some acreage he’s clearing for additional cattle grazing. He stops to pump diesel fuel from a large drum in the back of his truck into his John Deere motor grader.

He has 80 head of cattle, and he’s doing all the work himself — tearing out shrubs, planting dryland grasses and hauling fattened calves to market in Cedar City, Utah.

None of this will make him rich. But he loves working the land — and even more, he loves having a place where his grandkids can camp and cook smores and ride horses and four-wheelers. His voice swells with pride when he tells us how one of his grandsons, who lives in the Phoenix area, tried to re-create his cattle brand for a school crafts project.

“This property is not mine. It’s our family’s, and it’s my generation’s stewardship right now to take care of it,” Hafen says.

Over the hum of the fuel pump, he points to a nearby ridge, where someday he’ll see the towers of TransWest Express.

We get back into his truck and slowly ascend Mud Springs Road, surrounded by ponderosa pines. Hafen’s biggest problem with Anschutz’s project isn’t the power line itself, but rather the service roads that will run alongside it near his land — mostly upgrades to existing roads, which the company says it will restore to their current condition after construction, but also a few miles of new road that may be needed.

Hafen worries those changes will bring an influx of outsiders to this remote backcountry. Already, he says, tourists in off-road vehicles veer off dirt paths, trampling grasses and leaving tire tracks that can last for years.

“It’s not that we’re anti-people. But there’s too many people that don’t have respect for anybody’s anything,” he says. “Everything in our old schoolhouse disappeared the same way — all the old books, all the old desks. People just grab it and take it.”

Separate from the power line, Hafen worries about a local spring that irrigates his ranch. Over the 15 years he’s measured the flow, he’s seen it as high as 600 gallons a minute. Lately, it’s been as low as 350. His dad has never seen such low flow.

I ask Hafen if he thinks there will be enough water to sustain ranching here long term, or if he’s concerned that ever-worsening droughts could put an end to his family’s tradition. If he could answer that question, he says, “I’d have an inside to God.”

“I don’t have a real strong belief in global warming,” he says. “I think things change, yes. But it tends to go up and down.”

We stop along Mud Springs Road to see something I’ve been looking for all week — a survey marker for the transmission-line route. It’s got a 2017 date stamp — a reminder of just how long it’s taking Anschutz to send wind power to California, and reduce the fossil fuel pollution that’s heating the planet and drying out Western springs like the ones Hafen depends on.

There’s another survey marker up the road, at the base of a hill where Hafen likes to take his binoculars and look for elk. He leads us up the hill on foot, past pines and sweet-smelling sagebrush and delicate wildflowers. At the top, we’re rewarded with a glorious view of a sweeping green valley. It’s one of the most beautiful places we’ve seen all week.

Hafen clambers up on a rock and points to where the power line will run — marring the landscape.

“It’s hard to express the love and the emotional feeling that country like this [evokes] in people that have been here their whole lives working on it, running cows on it, and what it means to us,” he says.

I mention all the studies showing a need for more electric lines through rural areas, to connect big cities with distant wind and solar farms. Hafen’s response surprises me. He doesn’t describe Anschutz’s project as evil or misguided. Instead, he says that a “small minority” of people live along these power-line routes, and that in America, “the majority always wins out.”

It would be easy for the West’s leading cities to ignore Hafen, and anyone else standing between them and the electricity they so badly need. They’ve done it before. They wield the political and economic power.

But that power also means it’s their responsibility to make sure the clean energy transition does the least harm possible — and where harm is unavoidable, to try to make up for it.

“We all understand it needs to happen,” Hafen says. “We just want to do it with the least impact that we can.”

Only when we get back into the truck does he tell me about his son, Skyler. Twenty-one years ago, the boy was riding a motorcycle to check on Hafen’s father out on the ranch, when he was hit by a vehicle coming around a blind turn. He was 10 years old.

Skyler’s death is the kind of tragic accident Hafen fears will happen again if a power line brings more traffic to the area.

“The more people, the less you can allow your kids to do,” he says, his voice quiet.

The point of this story isn’t that TransWest Express will kill children. It’s that for Hafen, a transmission line running within half a mile of his family’s land is intensely personal, in a way it never will be for Angelenos on the receiving end of the line.

TransWest will plug into the California power grid at Eldorado Substation south of Las Vegas — a mess of wires and transformers and other hulking electrical equipment, looking wildly out of place against the Mojave Desert creosote. When we arrive later that afternoon, the weather is hot and windy. A dust storm obscures the nearby mountains. We don’t stay long.

The changes needed to shield the West from the ravages of global warming won’t make everyone happy. They’ll require trade-offs, and compromises, and probably some sacrifices we’ll come to regret.

But what other choice do we have?