- Share via

DELTA, Utah — The smokestack at Intermountain Power Plant looms mightily over rural Utah, belching steam and pollution across a landscape of alfalfa fields and desert shrub near the banks of the Sevier River.

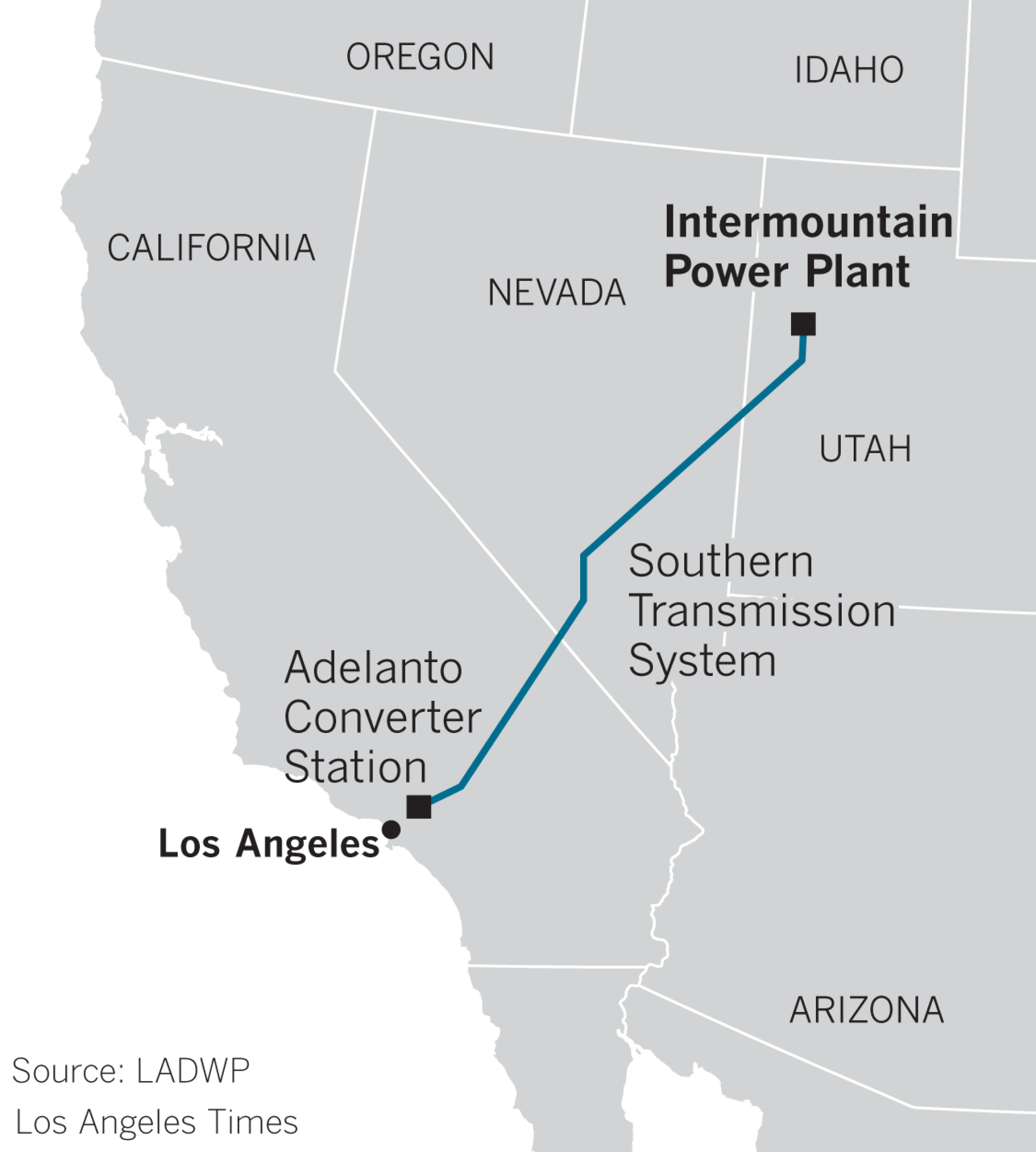

Five hundred miles away, Los Angeles is trying to lead the world in fighting climate change. But when Angelenos flip a light switch or charge an electric vehicle, some of the energy may come from Intermountain, where coal is burned in a raging furnace at the foot of the 710-foot smokestack.

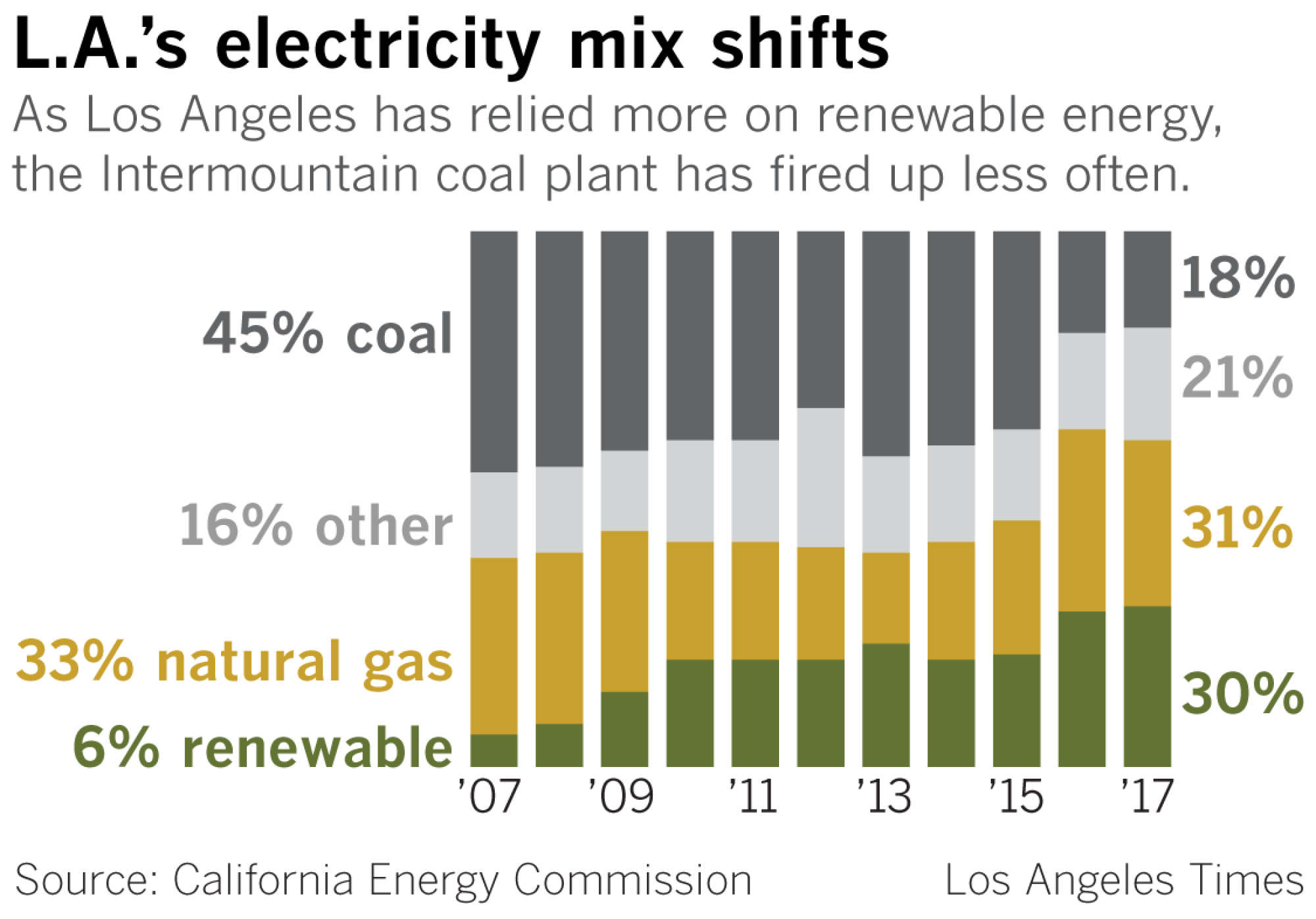

The coal plant has been L.A.’s single-largest power source for three decades, supplying between one-fifth and one-third of the city’s electricity in recent years.

It’s scheduled to shut down in 2025, ending California’s reliance on the dirtiest fossil fuel.

But Los Angeles is preparing to build a natural gas-fired power plant at the Intermountain site, even as it works to shut down three gas plants in its own backyard. Although gas burns more cleanly than coal, it still traps heat in the atmosphere. It also leaks from pipelines as methane, a planet-warming pollutant more powerful than carbon dioxide.

Critics say Los Angeles and other Southern California cities have no business making an $865-million investment in gas, especially when the state has committed to getting 100% of its electricity from climate-friendly sources such as solar and wind. L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti has touted his decision to close the three local gas plants as part of his own “Green New Deal” to fight climate change.

“Having taken our pitch and killed the new gas plants in the city, he’s got a big new one that’s still going to get built up there in Utah,” said S. David Freeman, a former general manager of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. “I don’t know how he reconciles his new position with going ahead with that.”

Los Angeles also hopes to import solar and wind power from the region, and to build a compressed air energy storage facility — basically a giant battery for renewable energy. Those projects, along with the gas plant, could provide an economic boost to Utah’s Millard County, where hundreds of jobs will disappear when the coal plant closes.

An economic lifeline

Before Intermountain Power Plant was built in the 1980s, Dean Draper said, Millard County “was still in the middle of the Great Depression.”

Draper was raised on a farm 10 miles west of Delta, a one-stoplight town with a population of about 3,500. Over lunch at Ashton’s Burger Barn — a family-run restaurant and butcher shop at the edge of town, where mounted deer and buffalo heads watch over patrons — he described a mid-20th century farming economy plagued by difficult soil conditions and challenging weather.

“There were a few people who did very well. But most people were kind of a hand-to-mouth existence,” said Draper, who serves on the Millard County Commission.

The coal plant changed everything.

In contrast to L.A.’s infamous Owens Valley water grab — which decimated that region’s agricultural economy — the megacity’s far-flung tentacles have been an economic boon for rural Utah. The 1,800-megawatt coal plant employs about 400 people, down from a high of 485. The average salary is $94,000, well above Millard County’s median household income of $59,000. There’s an on-site gym staffed by a wellness expert.

Intermountain Power Agency has paid more than $650 million in state and local taxes and tax equivalents over the years. The plant once accounted for 85% of the county’s tax base, down to a still-massive 35% today, Draper said.

One of the biggest beneficiaries is Millard School District, where kids have been able to study and play in state-of-the-art facilities unusual for a rural county.

On a gray and snowy morning this year, Keith Griffiths drove around Delta, showing off what the school district offers its nearly 3,000 students. Griffiths, the district’s business administrator, stopped at Delta High School, whose 3,200-seat gymnasium has hosted basketball tournaments, concerts and civic events. At the district’s technical center, teenagers and adults can learn skills such as welding, robotics and nursing.

Before the coal plant, Griffiths said, “most kids had to move away unless they could stay with their family farm.” After Intermountain was built, many of those kids were able to stay.

The coal plant has been a “darn good neighbor,” Griffiths said.

Soon the generators will be dismantled. And locals have realized that whatever Los Angeles gives, Los Angeles can also take away.

“Once in a while you’ll hear someone say, ‘I wish they never built the damn thing.’ But that’s rare,” said Scott Barney, Millard County’s economic development director. “It’s been our greatest blessing, and in some ways now our greatest curse.”

‘It’s hard to have their hands around our throats’

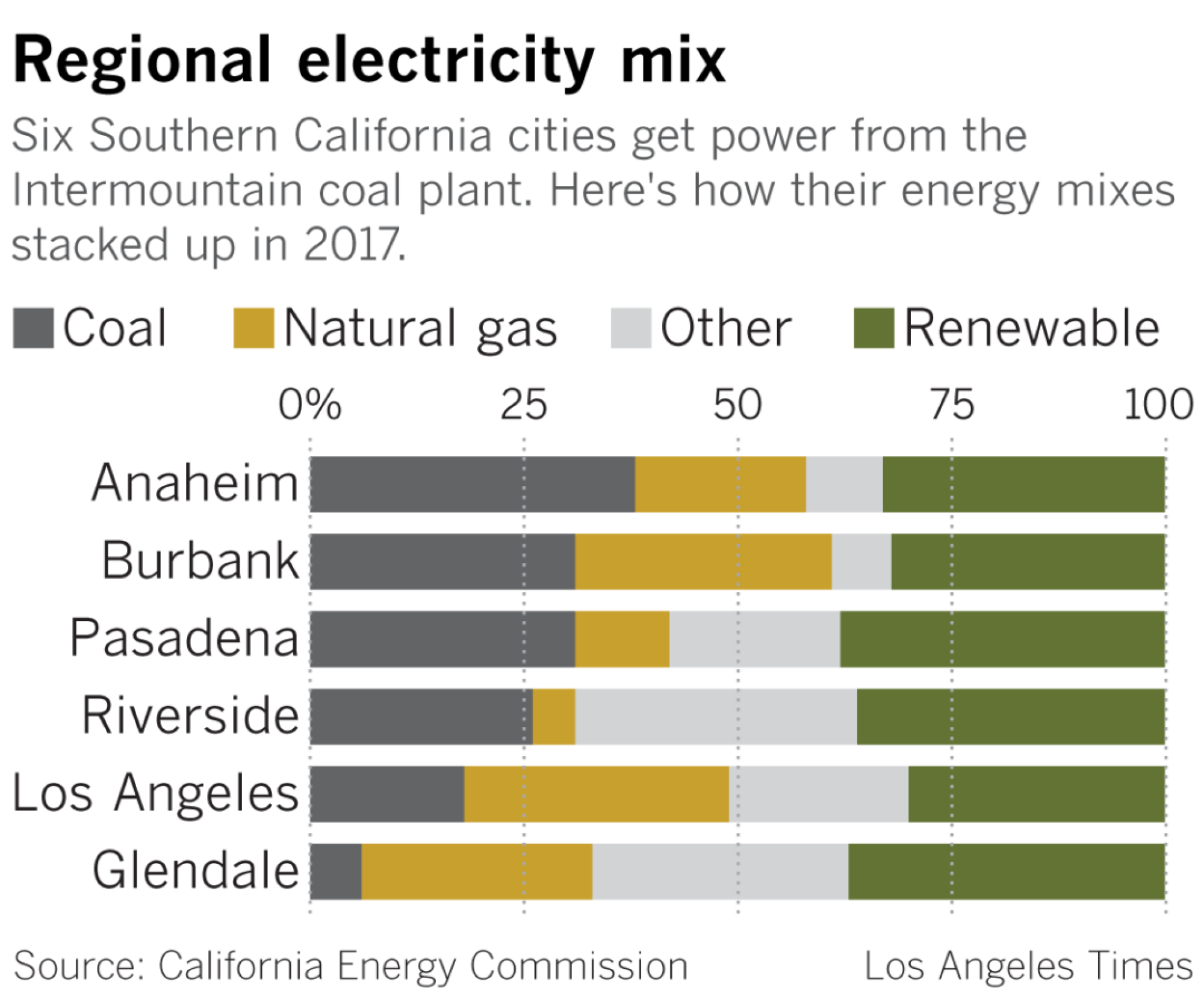

Los Angeles partnered with five other cities — Anaheim, Burbank, Glendale, Pasadena and Riverside — to build the coal-fired generating station in rural Utah. L.A. would have the rights to nearly half the power.

The $5.4-billion project fully opened in 1987, just before global warming began to enter the national consciousness.

Intermountain officials say they operate one of the country’s cleanest coal plants, thanks to pollution-control equipment paid for by California ratepayers. Residents of Delta, 10 miles south of the plant, say they don’t notice or don’t mind the air pollution.

Plant manager Jon Finlinson, who has worked at Intermountain since 1983, is proud of the facility’s track record. Asked during a recent tour about the plant’s impending closure, he responded flatly that he finds it “really depressing.”

“It’s by far the best industrial facility in the Intermountain West,” Finlinson said.

Although it’s cleaner than many other coal plants, Intermountain emits huge amounts of nitrogen oxides, a component of smog. Groundwater near the facility’s on-site landfill is badly contaminated with several dangerous chemicals, according to a recent report from the Environmental Integrity Project. And over the five-year period that ended in 2017, Intermountain generated more than 49 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, making it the sixth-largest climate polluter in the American West.

California has known for years it would eventually have to stop buying power from Intermountain. But the breakup has been long and painful.

Officials in Burbank, Glendale, Pasadena and Riverside briefly talked up the idea of extending their coal contracts past 2027, before a state law barring them from doing so took effect. They quickly abandoned the idea. Los Angeles and its neighbors later agreed to build a 1,200-megawatt gas plant at the Intermountain site, before LADWP decided the facility should be downsized to 840 megawatts.

The whiplash has left Millard County officials feeling powerless.

“It’s hard to have their hands around our throats,” said Wayne Jackson, who serves on the county commission.

Physics and politics

LADWP officials say they have several reasons to build a gas plant in place of the coal facility.

For one thing, natural gas will help them keep the lights on. Solar and wind can’t be relied on 24 hours a day, seven days a week, at least not without big amounts of energy storage. As the city works toward eliminating fossil fuels — its electricity was 30% renewable in 2017 — LADWP wants to keep operating some plants that can generate energy around the clock.

Reiko Kerr, LADWP’s senior assistant general manager for power system engineering, said the utility is working toward a 100% clean energy future.

“That’s coming. We recognize it,” Kerr said. “But we also recognize, if you go totally off gas immediately, you’re not going to be able to meet federal reliability standards, and that’s not acceptable either. So trying to balance those two is the real challenge.”

The new gas plant, slated to begin construction by Jan. 1, will also help Los Angeles increase its use of solar and wind power, LADWP officials said, because it will give them the physical ability to move clean energy through the 488-mile transmission line from Utah to California that currently moves coal power.

Luis Jansen, an LADWP electrical engineer, listed several technical considerations he said would make it difficult to import renewables over the power line without fossil fueled generators at the other end. He said a minimum amount of “firm generation” is needed to operate the converter station outside Delta that transfers power to the high-voltage, direct-current transmission line. The gas units will also stabilize and strengthen the utility’s electrical system, Jansen said.

Politics played a role in LADWP’s decision-making too.

Utah’s Intermountain Power Agency owns the coal plant and the power line, known as the Southern Transmission System. If Los Angeles had simply allowed its contract to expire, LADWP officials said, the Utah agency could have blocked L.A.’s efforts to import renewable energy.

The agency agreed to let L.A. keep using the power line. But in the absence of coal, Utah wanted a gas plant, for the jobs and tax revenues it would create. LADWP estimates the new facility will employ about 125 people — a fraction of current employment at Intermountain but better than nothing.

LADWP sees the Southern Transmission System as crucial to its renewable energy strategy. There’s limited space to build solar and wind farms in the Los Angeles Basin, but Utah and its neighboring states have plenty of land.

There’s also value in sourcing renewable energy from across the West, because the sun shines and the wind blows at different times of day in different places.

“We try to maximize the benefit of the assets that the ratepayers have already paid for,” LADWP’s Kerr said. “So let’s look for renewables where we already have transmission.”

‘They don’t need to burn gas’

Those arguments haven’t convinced clean energy advocates.

Power companies across the state are shutting down existing gas plants and canceling new ones. That trend has been driven by the improving economics of solar and wind power, a growing understanding that non-fossil energy technologies can stabilize the power grid, and the increasing urgency of the climate crisis.

“Business-as-usual decision-making will not cut it right now,” said Evan Gillespie, an activist with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

Gillespie questioned whether Utah’s Intermountain Power Agency would ever block L.A.’s access to the Southern Transmission System. The wires have no economic value except to transmit electricity to California.

“It’s not like IPA can pick up that line and move it to Oregon,” Gillespie said.

What’s more, half a dozen power grid experts interviewed by the Los Angeles Times disputed LADWP’s claim that it needs a gas plant to move renewable energy over the transmission line.

Several non-emitting technologies can provide the power grid services LADWP needs, the experts said. Those technologies include “synchronous condensers,” basically big motors that can mimic some of the functions of traditional generators.

LADWP has used synchronous condensers since the 1930s to help transmit electricity from Hoover Dam, said David Olsen, a member of the governing board of the California Independent System Operator, a nonprofit corporation that runs the power grid for most of the state. Olsen characterized the technical limitations described by LADWP as “the arguments that the gas generators and traditional utility folks always produce when they’re trying to push for the approval of new gas generation.”

“They don’t need to burn gas to get the electrical capabilities that they’re talking about, which they know very, very well from their own experience,” Olsen said. “The electrical issues are real, but they can be solved by non-fossil technologies.”

Los Angeles could also upgrade its converter station at Intermountain — which transforms electricity from alternating to direct current — with “voltage source” technology better suited for transmitting renewable energy.

LADWP studied voltage source converters and determined they were “not mature enough” for overhead lines as powerful as the Southern Transmission System, said Paul Schultz, the utility’s director of external energy resources.

But several experts told The Times that the technology is ready or nearly ready to handle the kind of system LADWP operates. Representatives of two global engineering companies — Siemens of Germany, and ABB of Switzerland — said they offer voltage source converters that can reliably operate an overhead line with the technical specifications of the Southern Transmission System.

“This is definitely within the capabilities of the technology today,” Siemens engineer Frank Schettler said.

LADWP is planning an $840-million project to replace the converter stations at each end of the power line, using the same type of technology installed in the 1980s, rather than voltage source converters.

Between the converter stations and the gas plant, the Intermountain overhaul is projected to cost $1.7 billion overall. Los Angeles will pay the vast majority of those costs.

‘Cautious, conservative thinking’

Figuring out how to run power lines without fossil fuels isn’t just a problem for Los Angeles. Researchers studying the U.S. power grid have found that a national build-out of long-distance transmission is one of the cheapest strategies for dramatically reducing planet-warming emissions, because those wires allow cities to import cheap solar and wind power from rural areas.

Ric O’Connell, executive director of the Berkeley nonprofit consulting group GridLab, said LADWP was once on the cutting edge of changes in the power grid. Now he wonders if the utility is falling behind, at a time when climate change demands bold action.

“This cautious, conservative thinking isn’t going to work,” he said.

Of the other California cities that built the coal plant alongside Los Angeles, only Glendale has committed to the gas plant, with Burbank expected to confirm its participation soon. Anaheim, Pasadena and Riverside opted out of the gas contract or never signed up to begin with. Officials in those cities have cited the importance of complying with Senate Bill 100, the state law mandating 100% clean energy by 2045.

Gillespie, of the Sierra Club, said Los Angeles plays an outsize role in setting the global climate agenda. He pointed to former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s decision to end L.A.’s use of coal for electricity, back in 2009.

“Things started happening around the country. Other utilities noticed, and all of a sudden, what seemed impossible was possible,” Gillespie said. “So when L.A. says, ‘We have to build a gas plant,’ the opposite happens. It gives other utilities that are on the fence room to do the politically easy thing.”

The ‘death cough’ of gas

LADWP officials say they haven’t committed to burning gas past California’s 2045 target date for 100% clean energy, despite signing a 50-year contract that runs through 2077.

One possible solution, they say, is to retrofit the gas plant to run on renewable hydrogen. It’s not feasible using current technology and could be prohibitively expensive, but several companies are working on the technology, including General Electric, Mitsubishi and Siemens. Another option is to outfit the gas plant with equipment that captures its planet-warming emissions before they enter the atmosphere, should that technology ever become commercially viable.

Los Angeles could also try to shut down the facility ahead of schedule, which would require a new round of potentially contentious negotiations between the California and Utah parties.

“If the power purchasers don’t want to run the plant, they don’t have to. They just have to pay off the debt,” Intermountain Power Agency spokesman John Ward said.

Asked recently about the Utah gas plant, Garcetti suggested he’s open to being convinced the city can do without it. If Los Angeles does build the facility, the mayor said, he hopes it will be “the death cough of gas-based electricity generation.”

“We are only doing that literally to get through the time in which we will make it obsolete,” Garcetti said.

Production by Jessica Martinez