The bricks, bombs and socialist utopias of Southern California’s labor history

Once upon a time... Los Angeles came this close to having a socialist mayor.

In 1911, Job Harriman, a labor lawyer and onetime minister who had run for vice president on the socialist ticket in 1900, won L.A.’s mayoral primary.

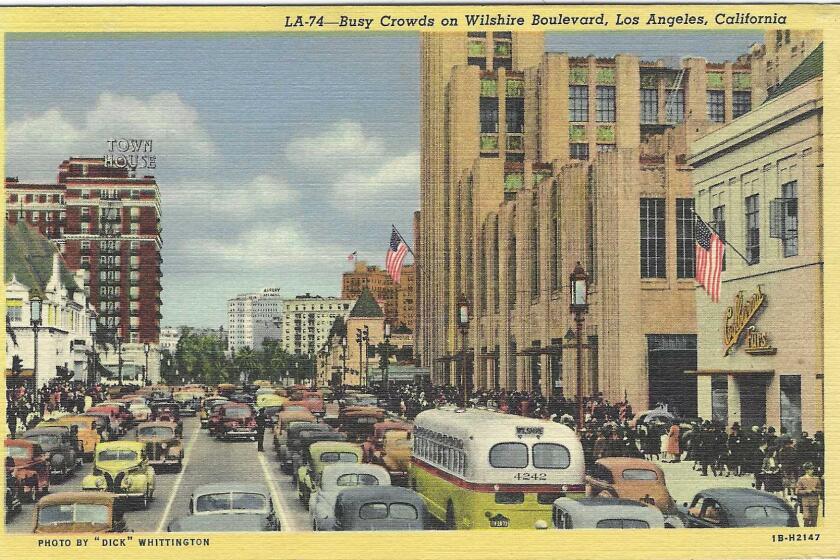

That was extraordinary in itself, but practically miraculous in a city that was a bloodied battleground between workers and labor organizers, and the anti-labor ferocity of L.A. businessmen in general and one in particular — Harrison Gray Otis, publisher of the L.A. Times, which was known to put “Labor Day” in quotes, and to headline an 1890 Labor Day account, “Immense parades … but no outbreaks or disturbance in any place.”

Otis fulminated and crusaded so venomously and brutally against labor unions that a fellow Republican — the good-government governor Hiram Johnson — said that in Southern California, anything that was “disgraceful, depraved, corrupt, crooked and putrescent: that is Harrison Gray Otis.” Otis returned fire. The governor, he said, was a “born mob leader,” and union leaders were “corpse defacers.”

Years of a constant churn of newcomers — Midwesterners along with Latinos, principally from Mexico — had given L.A. a lowest-bidder cheap labor pool that was hard to unionize. Carey McWilliams, the renowned liberal writer and publisher, pointed out that in the 20 years before Harriman ran for mayor, wages in Los Angeles averaged 20% or 30% below those in San Francisco, a famously pro-labor union city. And Otis and his fellow business leaders meant to keep it that way.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

So when unionized typesetters went on strike in 1890 after Otis cut their wages by 20% in an economic slide, Otis brought in strikebreakers. The hostility escalated, and remote L.A. was in the crosshairs of an unequal warfare between unions and workers, and a business oligarchy that demanded and got official help, like an anti-picketing ordinance that today would be tossed out as unconstitutional. Juries of the time refused to convict arrested picketers.

That was the crest that Job Harriman was riding to becoming L.A.’s mayor.

On the night of Sept. 30, 1910, out-of-town members of a militant union that had already inflicted property damage with bombs at non-union and anti-union sites around the country planted several bombs around L.A.

One, a suitcase full of dynamite, went off after midnight at the L.A. Times, where men were still working; 21 were killed. Otis’ enormous memorial to them still stands in the Hollywood Forever cemetery.

Three men, including a pair of brothers named McNamara, were arrested in April 1911. Harriman joined the defense team with the celebrated Clarence Darrow.

And in October 1911, Harriman won the mayoral primary.

But four days before the December general election, the McNamara brothers pleaded guilty, stunning an unsuspecting Harriman along with the labor leaders, supporters and voters who had believed the McNamaras’ claims of innocence and thought they were being railroaded.

The guilty plea cost Harriman the election, and gutted the labor movement in Southern California for decades.

Remember Harriman’s name; you’ll see it here again presently.

Now here we do a movie dissolve and change time and tempo, to a tale of three almost-cities.

Amid all of Los Angeles’ renowned utopian colonies, devoted as they were to nudes and foods, to fakes and fakirs, there were three labor-driven utopias of sorts; one of them was really a benevolent industrial dictatorship, one was a well-meaning plan for a factory community, and a third, founded as an idyll, vanished like a mirage in the desiccated desert where it was founded.

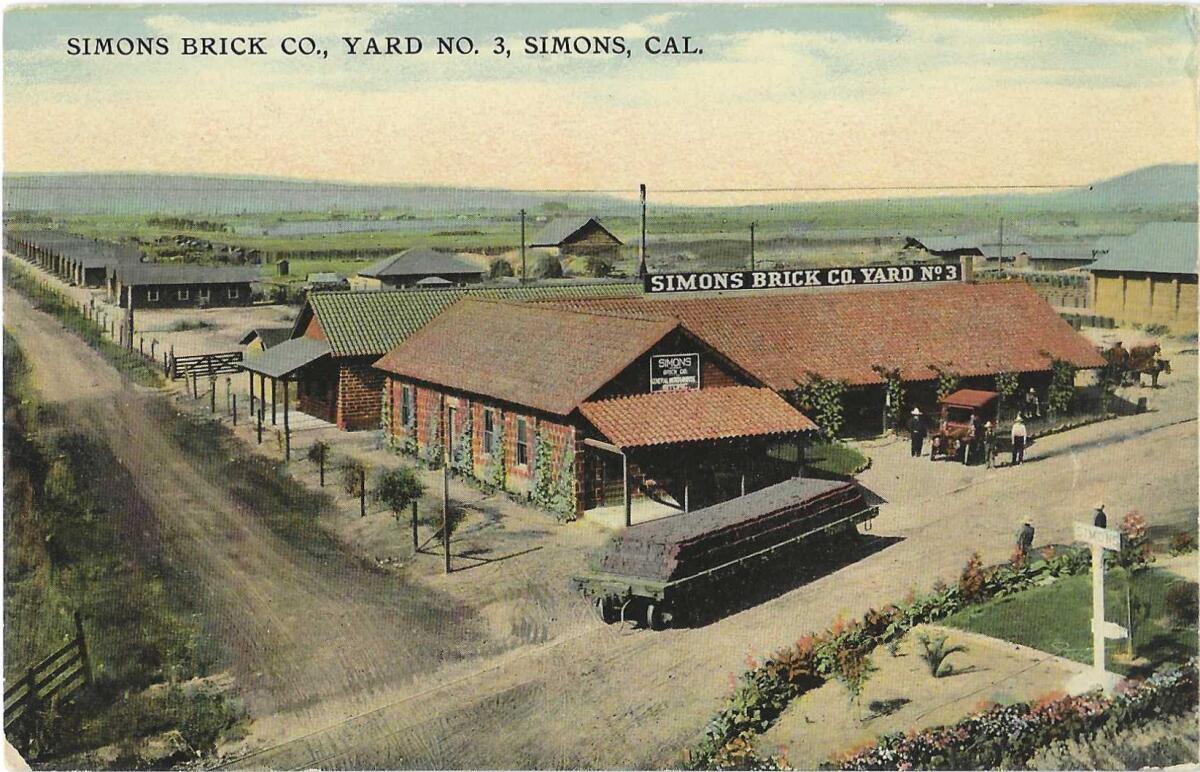

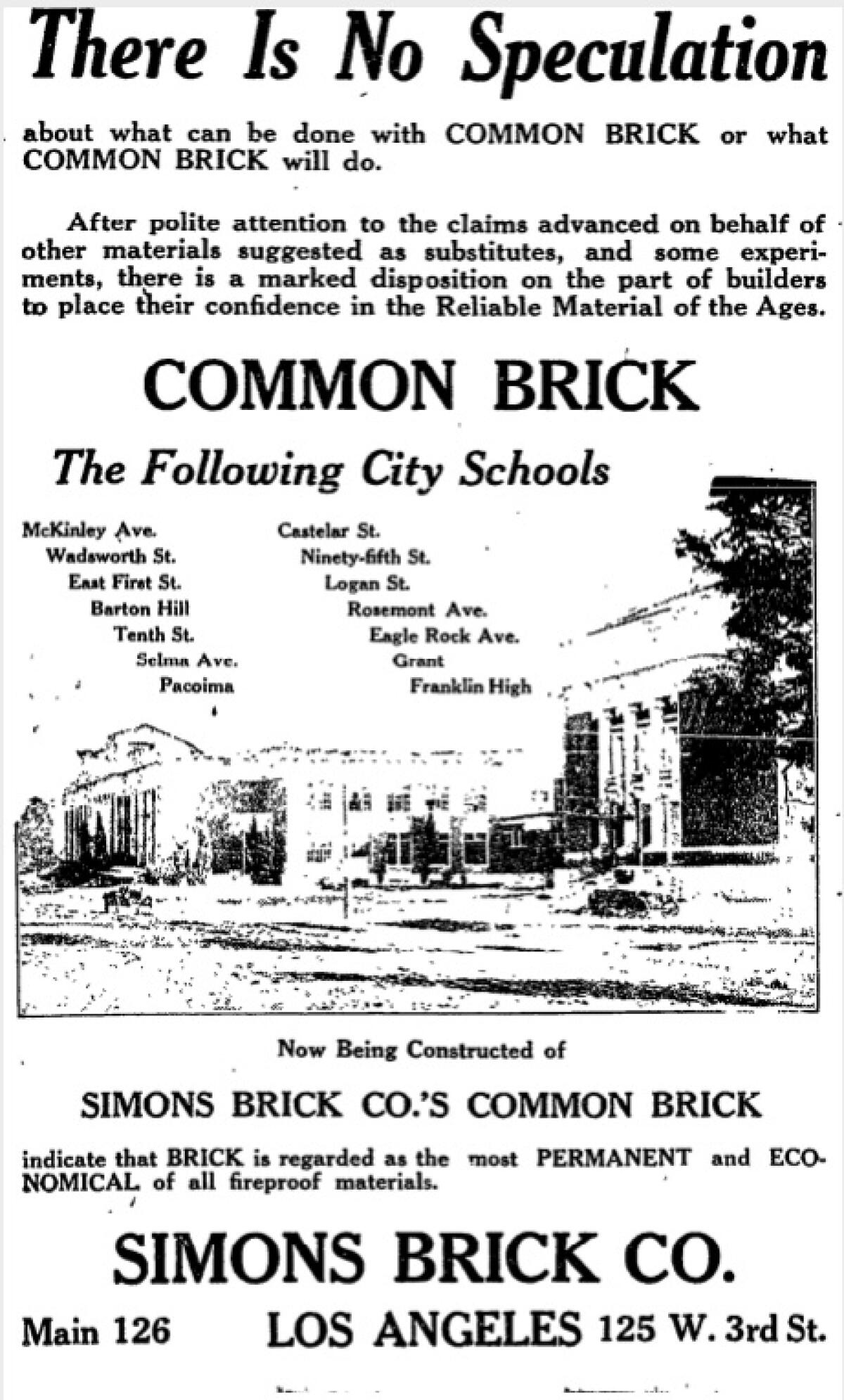

The first of them you can still find in evidence right underfoot. You see it sometimes in the patios and walls of older buildings — a brick stamped with the name “SIMONS.”

In the 1880s, the brick-making Simons family left Iowa for Los Angeles. It found the right kind of clay in Pasadena, and set up its brickmaking plant there (where the ardent Pasadena Humane Society had reason to have “arrested and arrested and yet again arrested” the Simons brothers, for the cruel treatment of company mules.)

Within a couple of decades, the large Simons family was running a large empire of eight brickyards, from Boyle Heights to Santa Monica.

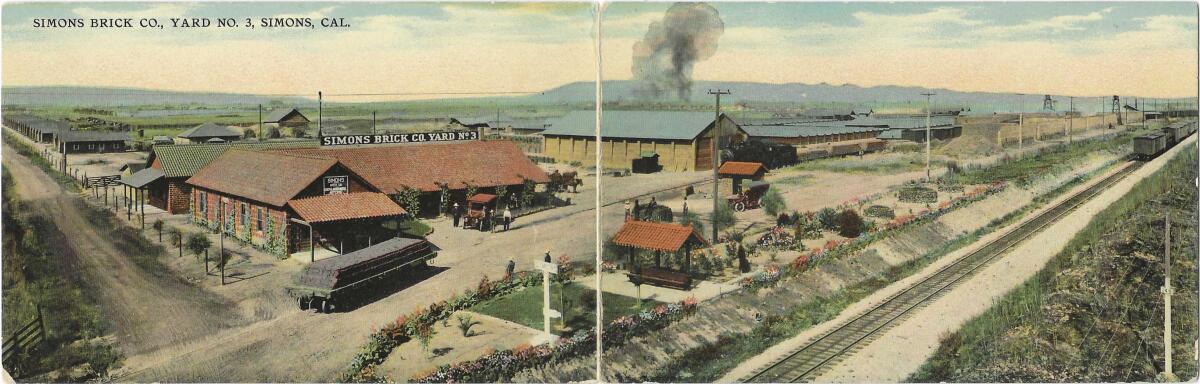

The best-known of them was brickyard No. 3, near Montebello, opened around 1905 on more than 250 acres, a mammoth enterprise turning out about 600,000 bricks a day, and a settlement called “Simons,” or “Simons Town,” the settlement the Simons family built for its workers.

To the good, it had houses, school, stores, a church built with Simons red brick and Simons red roof tile, post office, free healthcare, halls for billiards, dances and meetings. The daily wage was $2.25, and it rose to $3.50 a day in 1929. In the 1930s, when even U.S. citizens who were Mexican-American were being deported in order to clear out jobs for unemployed white Americans, the Simonses were said to have protected their workers. The men had a baseball team that played other cities’ and companies’ teams. The women had a softball team. The company band played in the Rose Parade once or twice. Every new baby born in Simons earned the family a $5 gold piece.

To the bad, Simons was there to guarantee a source of uninterrupted and amenable labor, many of them extended families from Guanajuato, Mexico. There were some Black workers and some “Americans,” a distinction The Times made in 1907. Workers paid rent for the insubstantial company houses, school classes were evidently in English only, and families were expected to spend their company paychecks at company stores. The work was perilous and exhausting, running 12 hours a day, seven days a week. The town gates were locked at night. One woman appearing in the 2012 short documentary “The Brick People” compared it to living on an army base.

Liquor was banned, which The Times claimed was “especially appreciated by the wives of the Mexicans.” (Bad as this sounds now, remember that one reason the temperance movement was able to make Prohibition the law of the land is that on paydays, far too many American working men spent all their wages in saloons and reached home with virtually empty pockets. But policing workers’ at-home behavior was in keeping with what Henry Ford’s busybody “sociology department” was pioneering in Michigan.) Simons had its own sheriff to keep the peace and be on alert for any talk of unionizing, which could get a man fired on the spot and evicted from this supposed industrial Eden.

Simons’ bricks helped to build Royce Hall and Walt Disney studios, and rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. Ambitious L.A. had a gobbling appetite for building materials. “BRICK FAMINE,” The Times headlined in 1912.

Several L.A. brick companies competed savagely for work, and Simons lost a huge contract for 20 million bricks for the city’s new sewer outfall project. Joe Simons himself set up a competing company after some arcane family quarrel in 1916, and ran it until he died 20 years later.

His brother, Walter, operated brickyard No. 3 until it closed, in 1952. Before Simons died, in 1954, his wife carried out the bequests which earned him a reputation for benevolence. Around 40 longtime employees, almost all of them Mexican American, were given between $3,000 and $6,000. “We’re Rich ... Estamos ricos!” ran The Times interviews with several of the men.

The protracted death of the Simons brick empire — of L.A. brickmakers in general — began after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, the force of which sent bricks shooting across streets “like cannonballs.” Unreinforced brick buildings still survive in California, but in places like L.A., you can see evidence of earthquake reinforcement: those little metal squares scattered over the facades of brick buildings, like the one in Koreatown that was the exterior of Jerry Seinfeld’s “New York” apartment building.

Angelenos can be spotted a mile away in other locales, waiting for the walk sign while locals jaywalk with abandon. What’s that about? And what happens when people do jaywalk here?

Los Angeles’ second “industrial utopia” lay just west of Alhambra.

Its name did not roll trippingly off the tongue: “Dolgeville,” for its founder, Alfred Dolge, a German-born piano maker and an authentic idealist who endorsed a kind of socialist utopianism that extended to the then-radical notion of worker pensions, insurance, and disability pay.

His original Dolgeville survives in New York state, where, true to his credo, Dolge built schools, parks, railroads, a theatre and library and other civic institutions for his employees.

When his businesses there failed, he came to Los Angeles, in 1901, for the same reason multiple thousands did and still do: to start again, and to get it right this time.

In 1903, the railroad magnate Henry Huntington staked Dolge to the money to start up a felt-making company on about 20 acres of the defunct San Gabriel Wine Company vineyards and winery abutting Alhambra. Right about now, you’re wondering … felt? Felt for piano keys, felt for pool tables, felt for slippers to export to China, felt for hats — felt was huge. “Dolge and Huntington are winners,” The Times wrote warmly of the partnership. “Idealist plans to build a town,” applauded the Los Angeles Herald.

That plan was for an industrial town, the felt factory joined by other manufacturers. And some did, notably a heating company and a metal pipe maker. The short-lived Dolgeville Land Company — whose directors included the father of World War II general George S. Patton — built affordable bungalows to sell to factory workers.

Like the town of Simons, Dolgeville also fielded an amateur baseball team, and had an official post office, a bank, and a firehouse, where locals met in 1906 to fulminate about the brothels and saloons thriving outside of the town limits.

What didn’t thrive was Dolgeville itself. The heater company burned in an arson fire, investors in the felt company weren’t happy with its progress, and by 1910, Dolgeville had been annexed to Alhambra. The felt factory was renamed Standard Felt, and kept going for at least another 50 years.

You can determine L.A.’s seasons by our plant life. For example, right now, it’s jacaranda-blooms-stuck-to-your-windshield season. And to understand the Southern California landscape you see, you have to realize that, like you, it is probably not from around here.

And now, the last of the three.

Remember Job Harriman, who lost the chance to be L.A.’s socialist mayor?

Two or three years after that election, he headed north, to the Antelope Valley, west of Palmdale, and founded the socialist utopian colony of Llano del Rio. It opened on May Day in 1914 — International Workers’ Day — and it would, Harriman believed, become a template and model for the sustainable pleasure and purpose of socialist, communal living.

Alas, like the biblical figure whose name he bore, this Job was plagued by tribulations there too — some of his own making, some of Mother Nature’s and some of human nature’s.

But in its brief time, Llano was “the most important non-religious utopian colony in western American history,” as Knox Mellon, the former head of the state’s office of historic preservation and an expert on the place and its people, told The Times in 1989.

Even then, preservationists were hurrying to save the fieldstone remnants of the scores of original homes and the kitchen, dining hall, school and hotel buildings abandoned by most of the thousand or so colonists a few years later.

As Llano struggled, The Times, in splashy headlines, missed no opportunity, and made a few of them too, to crow over every crisis that beset Llano: “Oligarchy of Misrule”; “Perquisites of Czar.”

Many townspeople who had bought investment shares in the place grew fed up with Harriman’s leadership and dicey finances.

Shades of today: At the heart of its doom, Llano was fatally short of water, especially for growing cash crops, and ranchers kept suing Llano over water rights. There was not much in the way of “rio” in the so-hopefully-named place, after all.

And human nature dealt its underhanded hand too. It was said that residents of the cooperative would not cooperate among themselves, that 14 people would be assigned to accomplish a task, but only four would actually do the work.

Beginning in 1918, Harriman began moving his philosophy and his colonists to Louisiana, to “New Llano,” which lasted until the mid-1930s. Harriman’s tuberculosis — a common ailment that sent thousands to California for a climate cure — got worse in damp Louisiana, and he came back to California, where he died in 1925.

There are volumes written about the epic labor strife of Southern California, about Llano del Rio, and about Simons, notably “The Brick People” by Alejandro Morales.

And even now, Angelenos are writing for themselves, and by themselves, the next chapter in how work is changing us, and — even better — how we are changing the nature of work.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.