Why don’t Angelenos jaywalk? It isn’t because nobody walks in L.A.

- Share via

Wherever you travel, in the great cities the wide world over you can always recognize the Angelenos.

We are the ones standing on a deserted street corner at midnight, waiting for the “walk” signal to change to green.

For the record:

10:31 a.m. March 3, 2021A previous version of this article mischaracterized one aspect of jaywalking law, saying it was illegal to enter a crosswalk while the “don’t walk” countdown was in progress. A California law that took effect in 2018 made it legal to enter a crosswalk during the countdown if a pedestrian can finish crossing before the countdown ends.

Let reckless New Yorkers and heedless Romans rush into manic traffic like deranged sheep fleeing the shepherd.

Here, we wait.

Most of us, anyway.

In 1983 in Los Angeles, where mythology holds that nobody walks, police ticketed 40,747 jaywalkers. In the same year in New York, where everybody walks, the number was 517. In the preceding 20 years, Chicago police had handed out none.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Yet then and now, pedestrians keep dying in L.A., often in poor neighborhoods with wider streets, fewer crosswalks and scant safety amenities. Advocates for the homeless go round and round with police over jaywalking tickets to homeless people who then go round and round with the law over tickets they can’t pay.

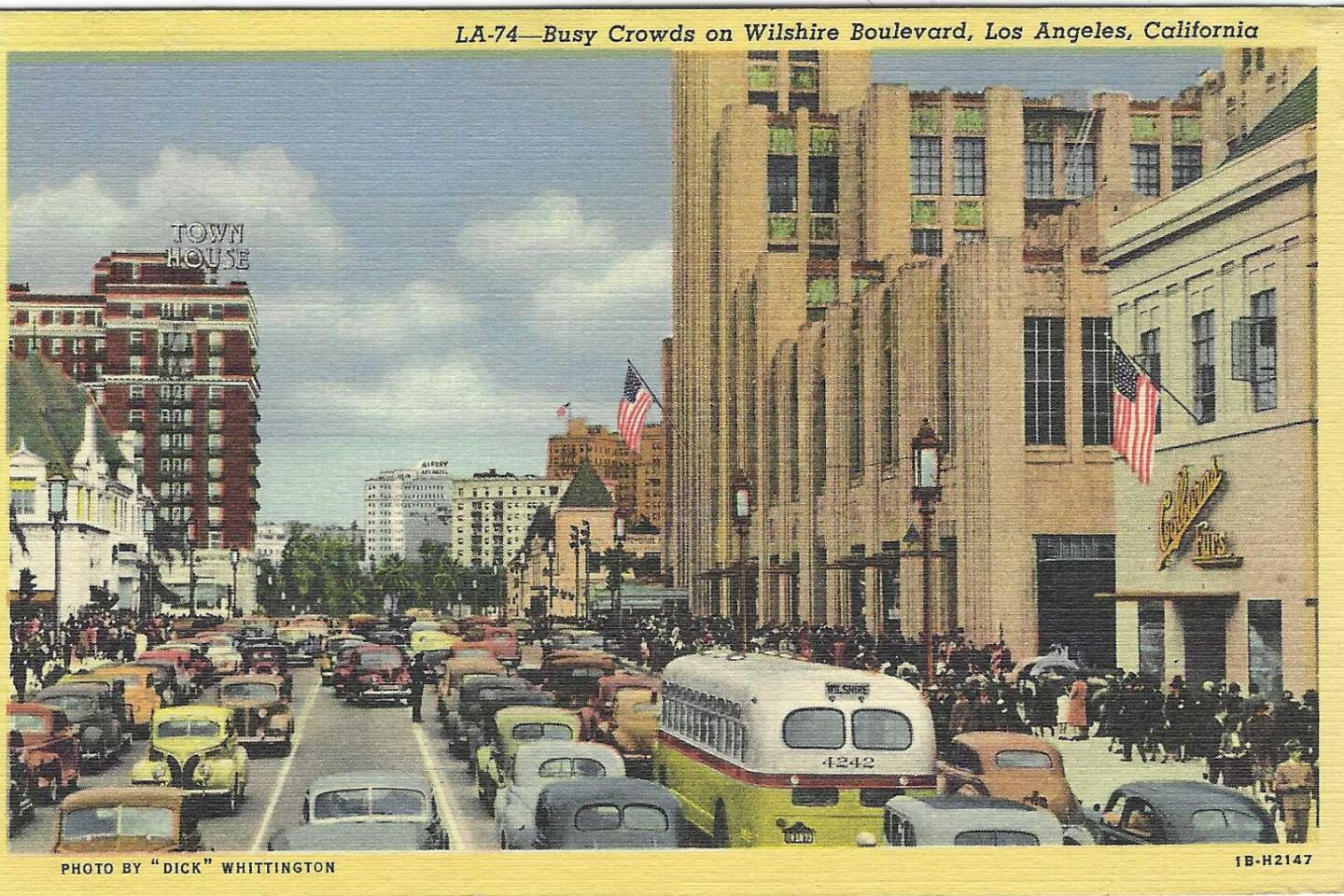

Beyond debate: 20th-century L.A. was designed for flivvers, not feet. Our wide, fast streets, iffy lighting and the human miscalculations of speed haven’t been reverse-engineered.

And for a mere infraction, jaywalking has the potential to get out of hand fast.

In July 1946, a Nazi death camp survivor who’d been here only six weeks was ticketed for jaywalking. The judge waived the $2 fine but lectured the poor man, with ghastly hyperbole, that jaywalking in L.A. is more dangerous than a concentration camp.

In 1954, two Santa Ana cops were suspended for using the chokehold on a man who’d refused to sign his jaywalking ticket. Almost 40 years later, an LAPD veteran was convicted of misdemeanor battery for twisting a Canoga Park jaywalker’s arm, kicking him, cuffing him and dragging him by his ponytail when the jaywalker — an immigrant from El Salvador — asked to have his citation read to him.

And in San Clemente last year, two Orange County sheriff’s deputies sat in their patrol car arguing over whether a Black man they spotted had jaywalked, and should they even stop him? They did, and within moments, the stop turned into a struggle, and the man was shot and killed.

The “jay” in “jaywalking” is from a quaint word for country folk — jays — who’d never seen the bright lights and big city and didn’t know any better than to plunge headlong into busy streets. But it’s the urbanized who dash confidently into the middle of the street and sometimes don’t make it to the other side.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

Yes, jaywalking in L.A. can be a very big deal, and “I didn’t see any traffic coming” is not a legit defense. You know you’re jaywalking if:

- You cross the street outside of a marked crosswalk or a controlled intersection, or at least 15 feet away from one.

- You don’t finish crossing the street before the countdown signal gets to zero. As of 2018, it’s legal to enter the crosswalk when the numbers are flashing in California so long as you can reasonably finish crossing before the timer runs out.

If you’ve ever been dinged for this, you are in exalted company.

On a fine June evening in 1980, a couple of fellows working for the Reagan presidential campaign got ticketed for jaywalking near LAX. The fine was $10. But they didn’t pay, and they didn’t pay, and Reagan won, and they got big jobs in the new administration, and in the fullness of time, arrest warrants went out for them.

One man was the new CIA director, William Casey, and the other was the new attorney general, Ed Meese. It took five years and some letters from the LAPD — one of them to Meese’s brother, who happened to run the DMV — before the tickets and fines were paid off and their records were clean.

Liberace was jaywalking across Ventura Boulevard in February 1954, and when he ignored his ticket, a warrant was issued for him too. His lawyer showed up in April with the $20 to settle the matter.

In March 1958, some LAPD cop with an abundance of chutzpah ticketed mobster Mickey Cohen for dashing out of the Pantages after a middleweight fight on a closed-circuit network, and right out into Hollywood Boulevard.

Out-of-towners get dinged a lot — perhaps disproportionately — because where they come from, jaywalking is just the shortest distance between two points.

In 1958, Miss Australia was literally just off the boat, here to compete in the Miss Universe pageant. An hour later, touring Hollywood, she leaped out of her taxi to hustle across Hollywood Boulevard for a photo of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. (Several numbers appeared in the story: the $5 jaywalking fine, and, in the smarmy style of the day, her measurements.)

And my favorite, the man who was stopped for jaywalking across a Glendale street in 1990 by two cops — who then recognized him from a composite drawing in roll call that very morning as the man was wanted for killing a gardener.

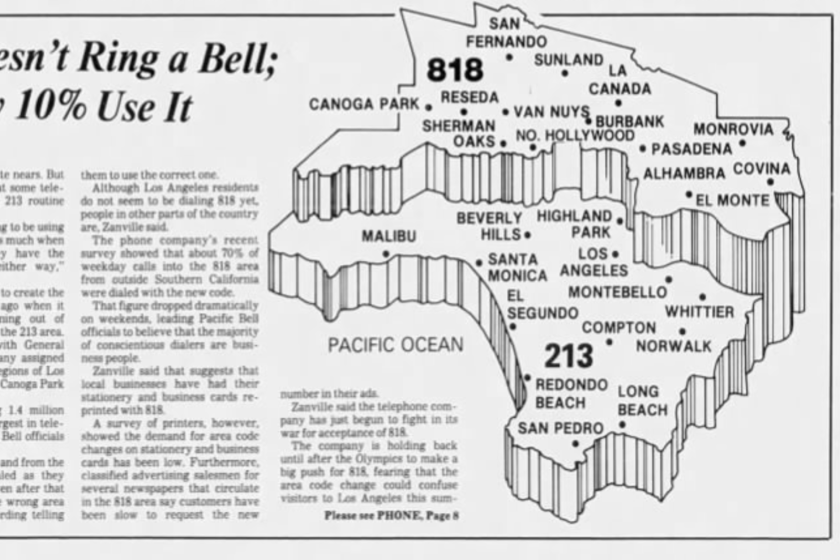

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

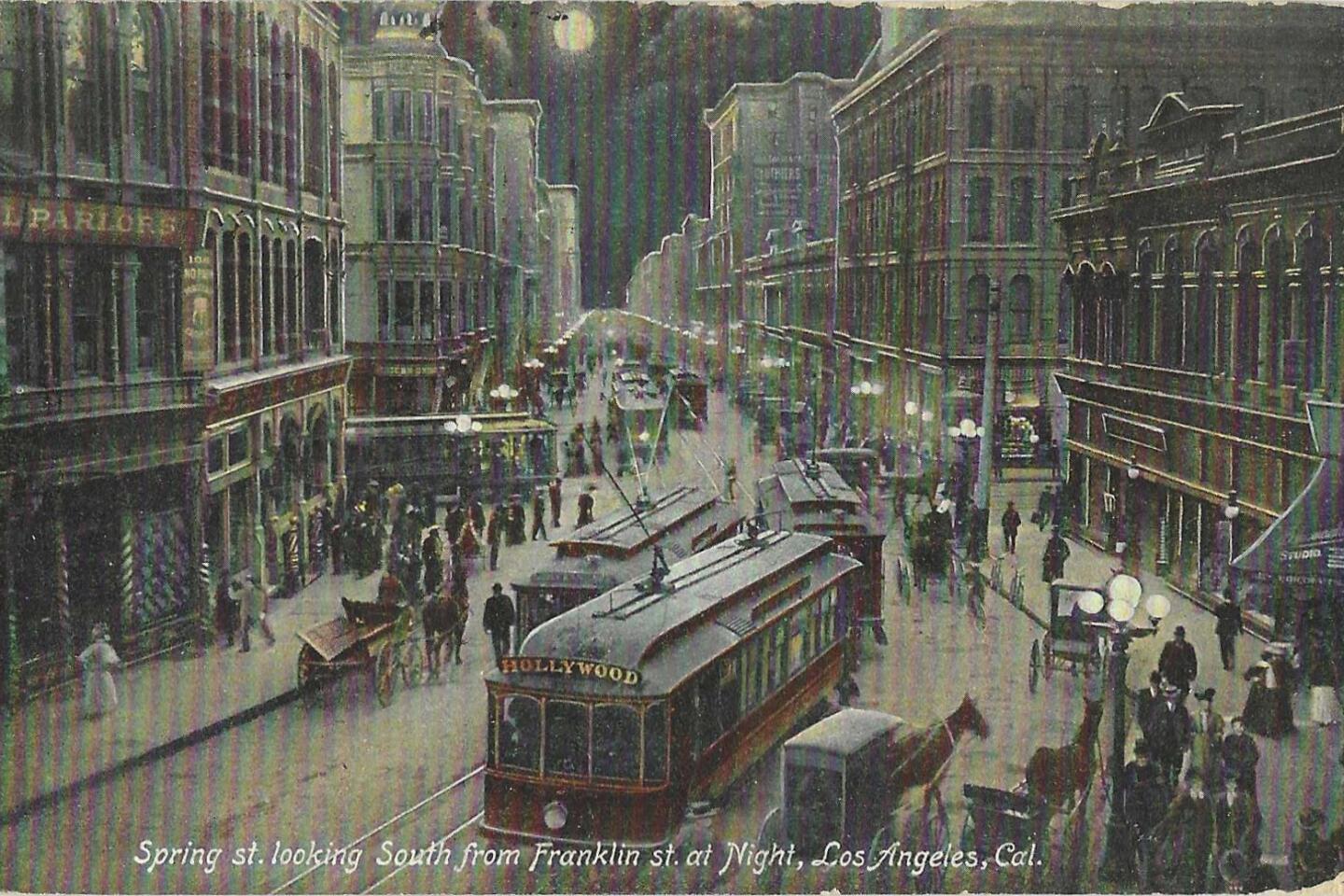

To read the news stories, L.A.’s first flowering of jaywalking, in the 1920s — a convergence of pedestrians and streetcars and new drivers in new Model Ts — was carnage central. On a single day in 1923, in different parts of town, two women were killed dashing into traffic.

During World War II, when service members and newcomers milled through downtown and Hollywood, their uniforms did not protect them from tickets. Neither did a judge’s robes. The presiding judge of the criminal courts was caught in a downtown jaywalking enforcement op.

In 1994, Jerry Rubin — one of the renowned Chicago 7 — was hit and fatally injured as he hurried across Wilshire Boulevard and into traffic in Westwood. His fellow Chicago 7 defendant, by then state Sen. Tom Hayden, remarked that “up to the end, he was defying authority.”

Helen Bernstein, a former teachers’ union president and an education reformer, was late for a speaking gig in 1997 when she dashed mid-block across Olympic Boulevard, a veritable whitewater rapids of traffic. She, too, died. In neither case were the drivers legally in the wrong.

And yes, someone did take jaywalking all the way to the Supreme Court. Edward Primbs went full-on 1776 to argue that obeying traffic signals reduced American citizens to “blind automatons who cannot be trusted to act save in response to stimuli.” Nerts, said the court.

You know who despised jaywalkers? Daryl Gates. The Los Angeles police chief took on all comers against insinuations that jaywalking tickets were just a yummy cash cow for the LAPD, or that jaywalking tickets were flat-out harassment — were anything, in fact, but protecting and serving the citizenry.

He glowered in a letter to the City Council about “an aggressive, undisciplined group of drivers and pedestrians.” He glowered in a letter to The Times in answer to a mocking essay by an unrepentant jaywalker. And in New York City, in 1992, he glowered as he legally crossed New York streets with my friend and colleague Geraldine Baum, headed to Rockefeller Center to talk about his autobiography on the “Today” show. All around him, every which way, jaywalkers — flagrant, brazen jaywalkers. The horror. The horror.

In Los Angeles, founded for Spain and a part of Mexico for generations, we pronounce our Spanish-language place names in a unique way.