When you think of a prison town, you probably think of a place like Huntsville, Texas. Or maybe Forrest City, Ark. Or Susanville, Calif. Even if you don’t know them by name, you know the type: places where the population is half-incarcerated and virtually everyone works for or knows someone who works for a prison. In short, you probably do not think of a place like Los Angeles.

But maybe you should.

Technically, it’s not a prison town. Though there are a few federal and state prisons for those convicted of serious crimes scattered across the county, the Southland’s claim to carceral fame lies more in its jails. On an average day, the county’s lockups hold close to 13,000 people. With roughly twice as many imprisoned people as are in New York’s far more notorious Rikers Island complex, Los Angeles is home to the largest jail system in the most heavily incarcerated country in the world.

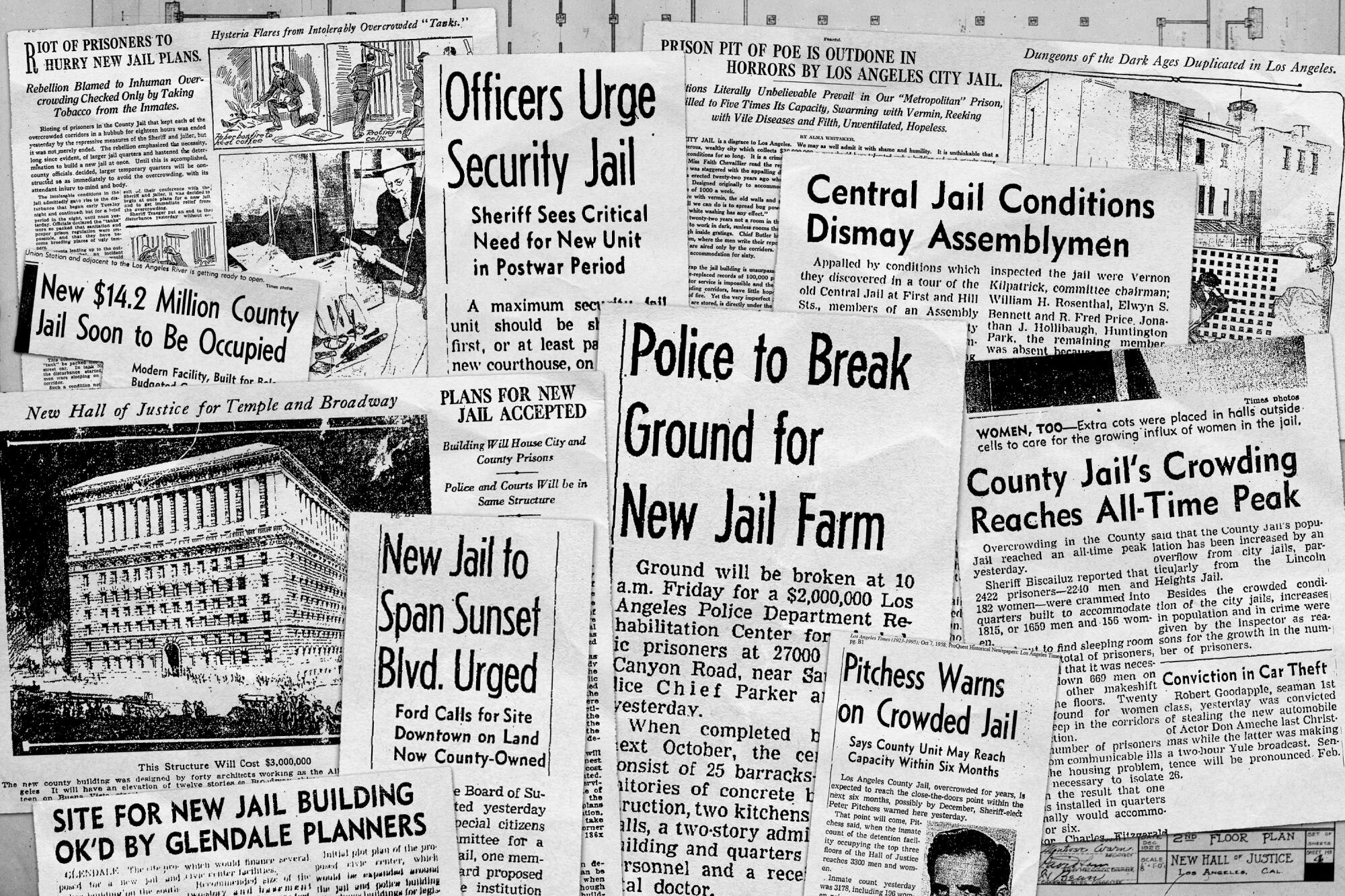

At nearly every moment in its history, Los Angeles has been either expanding an old jail, building a new one or debating whether to. The perpetual refrain of build, overcrowd, repeat hums in the background of the city’s history like an aging neon sign.

Right now, that hum is growing a little louder as county leaders once again take up the question of whether to replace Men’s Central. The crumbling downtown lockup mostly houses men awaiting trial or convicted of minor offenses; virtually everyone with any say agrees it is overdue for demolition.

“It’s so similar to the freeway issue,” said William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West and a professor of history at USC. “If we have a freeway that’s too crowded, we say, ‘Well, let’s build another one.’ How do we alleviate the problems in one prison? Well, we build another one.”

The region’s first jail was built on the edge of what is now downtown Los Angeles in 1786, when California was claimed by the Spanish Empire. At the time, it was used as a guard house for Spanish soldiers and known as the Cuartel Viejo.

But not long after it began to house inmates, the place became overcrowded — or rather it had a “bounteous patronage,” as The Times described it. Once it became too dilapidated to use, local leaders turned a cleric’s house into a make-do jail.

So in 1841 — still nearly a decade before California became a state — Los Angeles built what was technically at least its third jail, though probably the first one constructed for that purpose. But the simple structure at the corner of New High and Temple streets wasn’t intended for everyone. The white inmates stayed indoors. Their Native and Mexican counterparts were chained to logs outside.

The next jail was a one-story adobe structure on the corner of Spring and Franklin streets. It opened in 1853, during a period when Los Angeles — according to The Times — was said to be the “toughest town of the entire nation.” The growing city saw so many murders that the newspapers covered them like weather reports. One cheekily described the evening as a “brisk night for killing” after four men were shot to death in a town of just 3,500.

With the tougher town came a fuller jail, and in 1881 the city opened a lockup on West 2nd Street, with room for about 40 prisoners. The county followed suit and five years later opened the “modern” New High Street Jail, a three-story brick and stone Gothic structure. By the spring of 1887, the place was already overcrowded.

The city jail didn’t fare any better, and by the 1890s even the police chief had begun complaining about the cramped quarters in the West 2nd Street building, which now held several hundred men, women and children in a space designed for a few dozen. “The atmosphere in there becomes so foul that it is cruelty to keep any human being in it,” The Times wrote in 1894. “The authorities cannot escape the fact that the jail is much too small for the size of the city.”

So two years later, the city yet again opened a new jail, this time in a massive Richardson Romanesque building on 1st Street with room for twice as many prisoners as the old one. Within a year, it too was overcrowded. The police chief reported in 1903 that some prisoners had begun sleeping in hammocks and temporary cots, while others were forced to sleep standing up.

That same year, county supervisors green-lighted a 228-bed jail at the corner of Temple and Buena Vista. It was full by Christmas.

There wasn’t enough money to keep building jails by that point, so local leaders enlisted inmates on the city’s chain gang to build a stockade near Elysian Park to supplement the existing lockups.

“By 1910, Los Angeles already operated one of the largest jail systems in the country,” UCLA professor Kelly Lytle Hernández wrote in “City of Inmates,” her definitive history of Los Angeles jails.

Within a few short years, the local lockups were again beyond capacity. When Times reporters paid a visit to the city clink in 1916, they were horrified, describing the place as a “lice-ridden” and “hopelessly unsanitary” building with “unthinkably deplorable conditions” to which the “wealthy and prosperous city” could no longer be ignorant.

“How can we expect to make honest, healthy, reformed men by such unthinkable methods?” the paper asked. “If they come to jail sick they leave it worse. If they come in healthy and whole they leave it sick and dejected. There can be no excuse for such a state of affairs in modern times.”

The solution, according to the paper, was to build a new jail. The plan was for a “first-class, modern, airy, hygienic, merciful City Jail.” It would have sunlight and windows and would allow its prisoners access to towels, toothbrushes and the like. But those seemingly achievable goals turned out to be mostly aspirational for several years.

In the meantime, the city put up barracks for a prison farm in Griffith Park, which offered a little more freedom and sunlight for a couple of hundred arrestees. But inmates housed in the main jail continued to rot away in increasingly inhumane conditions.

And the county inmates weren’t any better off.

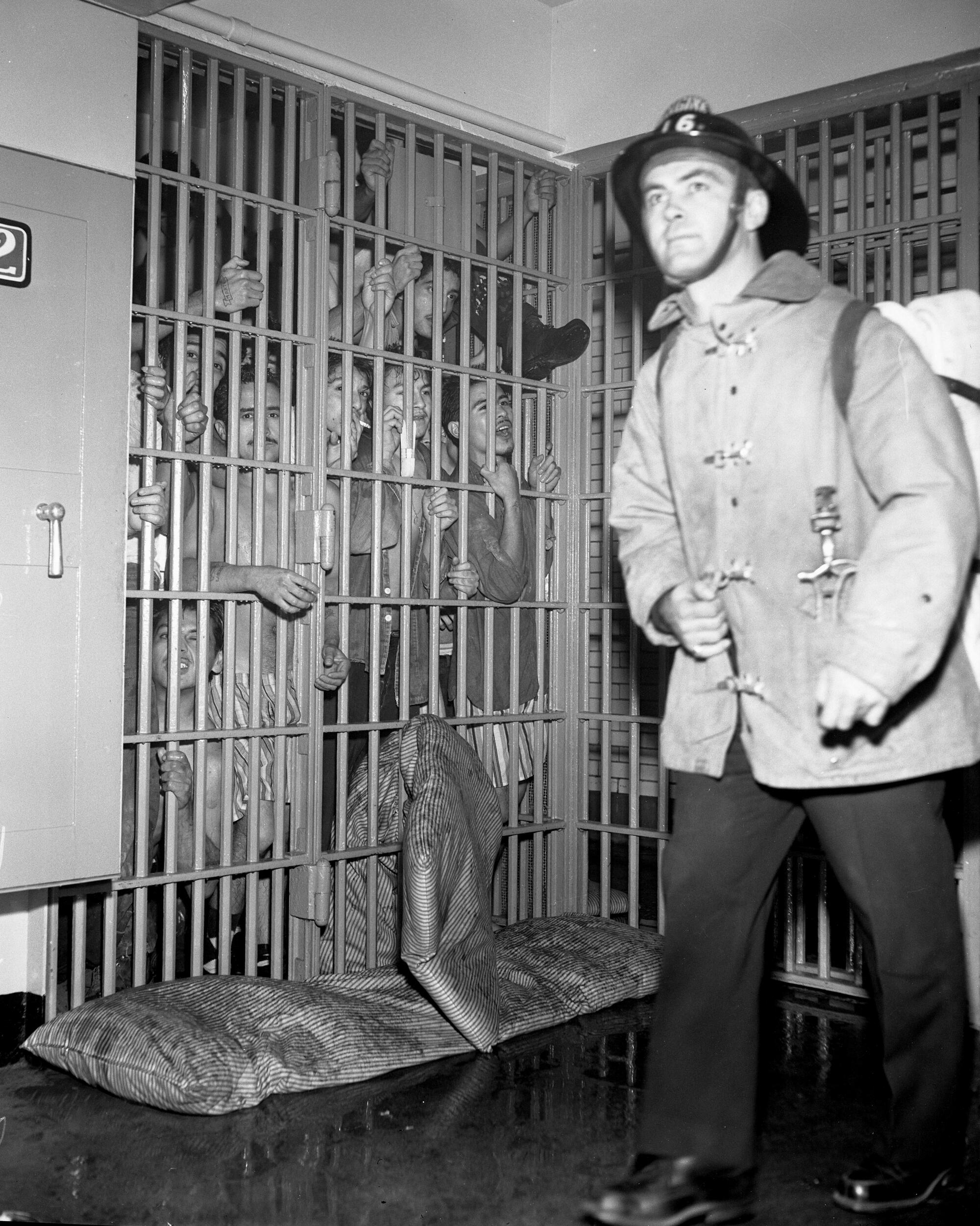

In March 1921, men locked up at the Buena Vista County Jail rioted. By that point the place was so overcrowded — nearly 450 people lived in quarters intended for 200 — that The Times took the side of the rioting inmates.

The spark for the unrest that spring was a literal flame: One man had been tossed in solitary confinement because he kept burning newspapers to heat his coffee. While in the jail “dungeon,” he allegedly conspired with some of the other men incarcerated there.

Fed up with sleeping in vermin-infested hallways, men pounded on cell doors, broke everything breakable and then threw pieces of the debris at anyone who passed by the cell bars. The result was, as usual, redoubled calls for a new jail.

“Again and again The Times has cried aloud against these wretched, crime-hatching, disease-breeding jail abominations,” the paper wrote. “For years it has urged the immediate construction of new jails and sanitary quarters for prisoners.”

A few months later, local officials heeded that urge and ordered designs for a County Hall of Justice, a 12-story Renaissance building to house all city, county and federal prisoners in its top five stories. By the time the first stone was laid in 1925, the cost had ballooned to $6 million.

Even that massive investment did not dampen the refrain of build, overcrowd, repeat. For the next few decades, it played out again and again in the all-caps headlines of The Times.

By 1958, the persistent crowding and poor conditions prompted one county supervisor to suggest building a 5-acre aerial jail-bridge, prompting the headline: “New Jail to Span Sunset Blvd.”

Fortunately, that proposed monstrosity did not materialize.

But why is that solution — the hum of carceral construction — such a constant in the City of Angels? There may not be a singular answer. In a recent interview, Hernández mused: “Is it that Los Angeles has a fantasy of itself being some kind of sunny utopia and therefore it needs to eliminate populations that infringe on that fantasy?”

The area has long been home to some of the nation’s largest Native, Black, Mexican and houseless populations, she said — all groups disproportionately targeted by incarceration. “So it follows that L.A. is one of the epicenters of incarceration,” she said. “It doesn’t mean we’re apart from everyone else. We’re in line with trends across the country.”

Often, however, the Southland has been at the vanguard of carceral trends. By early 1963, the county was nearing completion on two new jails that the paper alleged would finally “End Overcrowding at Hall of Justice.”

Together the buildings were expected to cost well over $20 million. The smaller of the new lockups — named after philanthropist Sybil Brand — featured pink walls and was designed to hold 915 women at a site in East L.A.

The larger one was Men’s Central Jail. Sitting on a 17-acre site downtown, it would hold 3,323 men. The Times described it then as “looking like a modernistic manufacturing plant.”

Starting in the mid-1970s, the jails’ deteriorating conditions ended up in the crosshairs of a series of federal lawsuits. When one of those cases — a class action filed on behalf of Men’s Central Jail inmate Dennis Rutherford — went to trial in 1978, the inmates won.

Judge William P. Gray declared the jail conditions unconstitutional and ordered a series of changes: The county jails needed to start giving everyone a bunk instead of making people sleep on the floor. They needed to let prisoners outside for an hour a day instead of 2½ hours a week. They needed to stop waking inmates before 6 a.m. for 16-hour trips to local courts and give them clean clothes at least twice a week.

In the decades since, the county has failed to do many of those things. Within a few years of Gray’s ruling, the jails were so packed that hundreds of still bunk-less inmates were given blankets and left to sleep on the roof.

Eventually the county built another massive downtown bastille known as the Twin Towers, a complex on the site of the city’s 1924 plague outbreak. The $373-million facility sat empty for several years because there was no money available to cover operating expenses. By the time the county’s inmate population peaked in 1993, there were more than 23,000 people living in its jails.

But even as the number of people in custody began a halting downward slide, the debates about when and how to expand L.A.’s jail facilities continued.

With needs of its own, the city in 2006 began erecting a $74-million lockup. And the county’s facilities were still so far beyond capacity — and some, notably Men’s Central Jail, in such disrepair — that conditions behind bars remained persistently abysmal, earning repeated rebukes from increasingly fed-up federal judges.

“In Men’s Central Jail, cells designed for three inmates are filled with six,” The Times wrote in 2010. “Last week, U.S. District Judge Dean D. Pregerson described the practice as ‘simply not consistent with basic values,’ noting that inmates did not even have the space to stand up and take a step or two.”

By that point Gray was no longer on the bench, so it was Pregerson who’d taken over the Rutherford case and decided that the situation behind bars “should not be permitted to exist in the future.’”

More than a decade later, it remains. Pregerson is still overseeing that case, as well as a second one focused on violence meted out by deputies and a third centered on problems with care for mentally ill prisoners.

“Everyone is on edge because it is crowded,” one inmate wrote in an affidavit filed in the Rutherford case two years ago. “The place smells of urine and excrement because some toilets don’t work, and people who are chained to chairs sometimes pee on the floor because the deputies won’t unchain them.”

In recent months, jail inspectors have raised concerns about rats, roaches and feces-smeared cells. Some men have begun complaining they don’t get enough food. This spring inspectors found that some inmates in cells with no cold water had rigged up a system to pass plastic bottles of it from cell to cell using strings. Just as in 1921, some men light fires to heat drinks or turn metal bunks into makeshift griddles to get a warm meal.

Although inmates are no longer chained to logs outside or sleeping on roofs, the glitchy HVAC systems mean the indoor temperatures sometimes drop into the 50s. Over the last two years, at least two inmates died after showing signs of hypothermia.

The jails still struggle to provide adequate sleeping quarters, and in recent years they’ve been caught leaving people to sleep on urine-soaked floors, using trash bags for blankets.

In 2019, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors scrapped its $1.7-billion plan to replace the decaying Central Jail with a jail-like mental health facility and, for five years, tried to pursue a no-new-jails strategy, focusing instead on lowering the jail population.

For the first time in years, the number of people in local lockups dipped below 13,000. But this year, with crime rates and political pressure rising, Los Angeles leaders changed course, raising questions about how many people they can really divert from the jails and whether looming legal changes once again could cause the county’s carceral population to balloon.

And so — after a pause — it resumes: Build, overcrowd, repeat.