The Prefecto Derbes, an Argentine coast guard vessel, shot at the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 when it attempted to evade arrest for illegal fishing. (Argentine coast guard)

Beijing has been securing access to restricted national fishing grounds by using business partnerships to register its ships under foreign flags — a process known as “flagging in.”

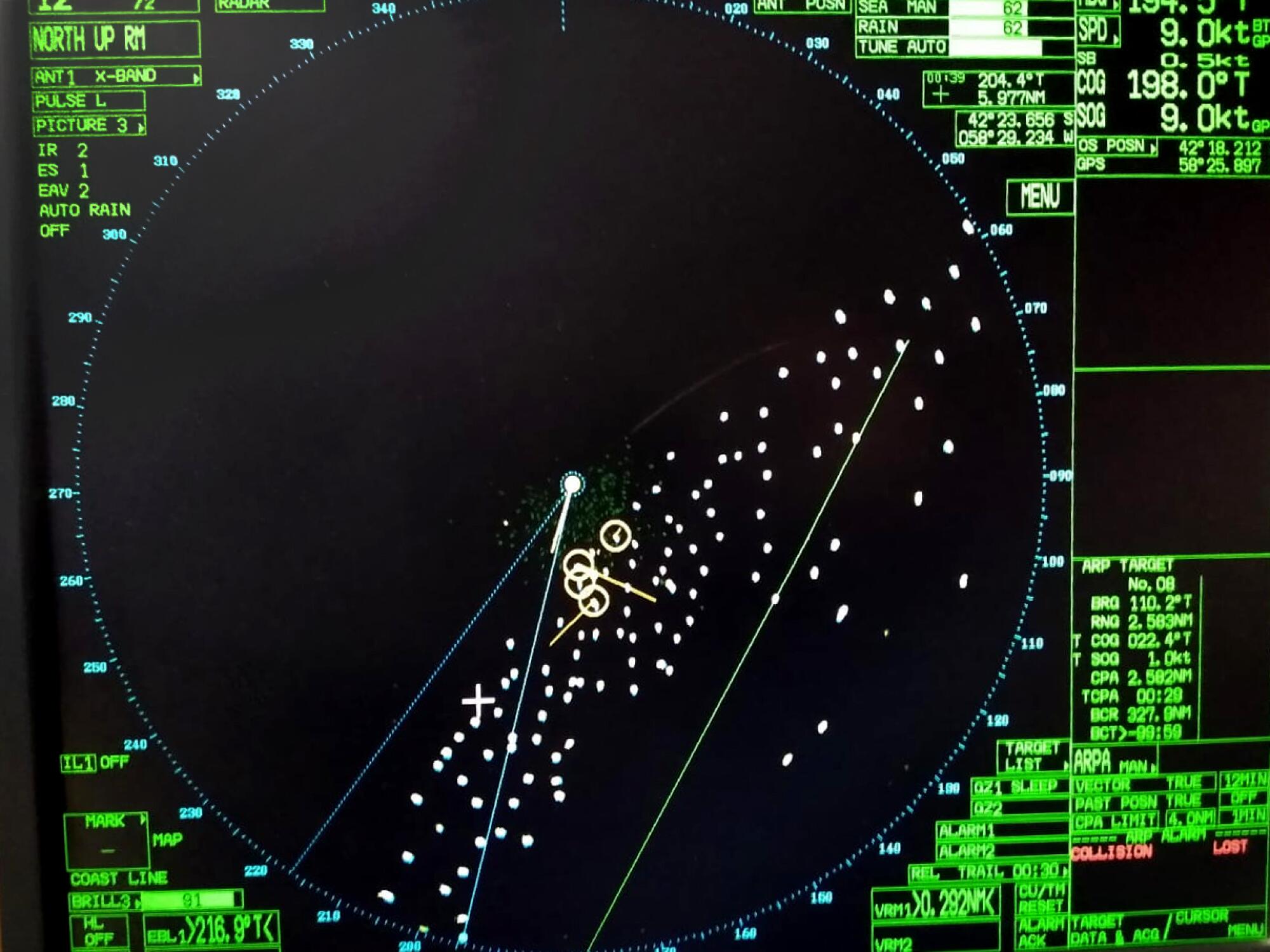

On March 14, 2016, in the squid grounds off the coast of Patagonia, a rusty Chinese vessel called the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 was fishing illegally, several miles inside Argentine waters. Spotted by an Argentine coast guard patrol and ordered over the radio to halt, the ship fled the scene. The Argentines gave chase and fired warning shots. Then the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 tried to ram the coast guard cutter, prompting it to open fire and sink the Chinese ship.

Although the violent encounter at sea that day was unusual, the incursion into Argentine waters by a Chinese fishing vessel was not. Owned by a state-run behemoth called the China National Fisheries Corp., the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 was one of several hundred Chinese jiggers — as squid ships are known — that routinely visit the fishing grounds that lie beyond Argentina’s territorial waters. Many of these ships turn off their locational transponders and cross secretly into Argentine waters. Since 2010, according to the Argentine government, the navy has chased at least 11 Chinese jiggers out of its waters.

A year after the sinking of the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10, Argentina’s Federal Fisheries Council issued a little-noticed announcement: It was granting fishing licenses to two foreign vessels that would allow them to operate within Argentine waters. Both would sail under the Argentine flag through a local front company, but their true owner was the China National Fisheries Corp.

The move by local authorities has become an increasingly common one in Argentina and around the world in recent years. From South America to Africa to the far Pacific, China has been securing access to restricted national fishing grounds by using business partnerships to register its ships under foreign flags — a process known as “flagging in.”

Of the 80 industrial squid-fishing vessels that fly the Argentine flag, 62 are controlled by Chinese companies. In all, China operates at least 249 flagged-in vessels, including ones that fish off the coasts of Micronesia, Kenya, Ghana, Senegal, Morocco and Iran.

Even before China began putting the flags of other countries on its boats, it reigned supreme in global fishing. It achieved its dominance on the high seas — beyond any country’s jurisdiction — with more than 6,000 distant-water ships, more than triple the size of the next largest national fleet.

The Chinese fleet has a well-documented reputation for violating international laws and standards against overfishing and abusing its crews in the drive to satisfy a growing and unsustainable global appetite for seafood. Amid continuing depletion of the world’s fish stocks, workers on Chinese boats on the high seas have been kept against their will and allowed to die of malnutrition.

The practice of flagging in threatens to make these problems local. In many of the countries China has targeted, governments lack the finances, the coast guard vessels or the political will to board and spot-check fishing ships and enforce the law.

And because seafood is an essential source of protein and fishing provides an important source of employment, experts say the encroachment into national waters by Chinese ships is compromising local food security and jeopardizing local livelihoods.

The Argentine Coast Guard found the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 fishing illegally in national waters in March 2016. (Argentine Coast Guard)

Trade records show that much of what is caught by these vessels is sent back to China, but some of the seafood is also exported to countries including the United States, Canada, Italy and Spain. “It’s a net transfer from poorer states who don’t have the capacity to protect their fisheries, to richer states who just want cheaper food products,” said Isaac B. Kardon, senior fellow for China studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Drawing on satellite information, business and maritime records, court filings and local news reports, the Outlaw Ocean Project created a database of Chinese-owned fishing ships that are flagged to other countries and fishing in their waters. It shows that in the last six years, more than 50 of these ships flagged to a dozen nations, including Argentina, have been implicated in illegal fishing, unauthorized transshipments or forced labor.

A total of 115 are approved to export their catches to the European Union, and since 2018 more than 70 ships have sent 17,000 tons of seafood to the United States.

The Chinese fleet has long targeted other countries’ fisheries. Typically that meant anchoring in international waters along sea borders, then running incursions into domestic waters. But the softer approach of “flagging in” has several advantages: It is less likely to result in political clashes, bad press or sunken vessels.

Although many nations have laws that require vessels fishing in their waters to be locally owned — with the aim of keeping profits in the country and making it easier to enforce fishing regulations — China has found ways around them. Chinese companies partner with locals, or even sell or lease their ships to them, but retain control over decisions and profits. Or they buy their way into local waters with “access agreements.”

In Argentina, which relies heavily on China as a source of investment, experts said the government’s decision to flag in Chinese-owned vessels appeared to violate restrictions on foreign ownership. Eduardo Pucci, a former Argentine fisheries minister, called it “a total contradiction.” The country’s fisheries council did not respond to a request for comment.

China has been upfront about how this approach factors into larger ambitions. In an academic paper published in 2023, Chinese fishery officials explained how they have relied extensively on Chinese companies to access Argentina’s territorial waters through “leasing and transfer methods,” and how this is part of a global policy.

The trend is especially pronounced in Africa, where Chinese companies operate flagged-in ships in the national waters of at least nine countries. “Fishing vessel owners and operators exploit African flags to escape effective oversight and to fish unsustainably and illegally both in sovereign African waters,” TMT, a nonprofit research organization in Norway that specializes in maritime crime, concluded in a 2022 report, adding that the companies were creating “a situation where they can harness the resources of a State without any meaningful restrictions or management oversight.”

At least 70 Chinese ships are flying the flag of Ghana and fishing in its national waters, even though foreign investment in fishing is technically illegal. The Environmental Justice Foundation, an advocacy group, reported in 2018 that the vast majority of industrial trawlers in Ghana have some element of Chinese control and that the fleet catches more than 110,000 tons of fish each year, contributing to a crisis in which the country’s fishing stocks have been depleted and the incomes of local fishermen have dropped by up to 40% over the last two decades.

In South America, the increasingly foreign presence in territorial waters is stoking nationalist worry.

“China is becoming the only player, by displacing local companies or purchasing them,” said Alfonso Miranda Eyzaguirre, a former ranking official in Peru’s Ministry of Production, which oversees the country’s fisheries.

China has also displaced fishing vessels from the European Union in the waters of Morocco. In the recent past, dozens of vessels, most of them from Spain, fished with the permission of the Moroccan government. The agreement lapsed in 2023, however, and China now operates at least six flagged-in vessels in Moroccan waters.

And in the Pacific Ocean, Chinese ships comb the waters of Fiji, the Solomon Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia, having flagged in or signed access agreements with those countries, according to a 2022 report by the U.S. Congressional Research Service. “Chinese fleets are active in waters far from China’s shores,” the report warned, “and the growth in their harvests threatens to worsen the already dire depletion in global fisheries.”

China’s methods are not historically unique. In decades past, American and Icelandic fishing companies have also used the tactic of flagging in. When criticized in the media for its fishing practices, China typically accuses its detractors of hypocrisy. At a news conference last year, a reporter asked Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin about allegations that his country engaged in illegal fishing.

He responded: “We call on the U.S. side to do its own part on the issue of distant-water fisheries first, rather than act as a judge or police to criticize other countries’ normal fishing activities.”

When Chinese fishing companies buy their way into the national waters of other countries, they are not doing it simply to increase their catch.

China has been expanding its influence in Latin America, Africa and the Pacific — and filling a void left by shrinking U.S. and European investment — through a global development program known as the Belt and Road Initiative. In exchange for well over $100 billion in loans to Latin American governments over the last two decades, China has at times received exclusive access to a wide range of resources including oil fields and lithium mines.

The oceans have been an important part of China’s campaign, which includes consolidating control over shipping, ports and fishing in foreign coastal waters. According to research by Kardon at the Carnegie Endowment, Chinese companies now operate dozens of overseas processing plants and cold-storage facilities as well as terminals in more than 90 fishing or shipping ports abroad.

Though most of these business ventures receive little public attention, some have sparked controversy. Starting in 2007, China extended more than $1 billion in loans to Sri Lanka as part of a plan for a Chinese state-owned company to build a port and an airport. The deal was based on the promise that the project would generate more than enough revenue for Sri Lanka to pay back these loans. By 2017, however, the port and airport had not recouped the project costs, and Sri Lanka had no way to pay back the loan. China struck a new deal extending credit further — and giving it majority control over the port and the surrounding area for 99 years.

In May 2021, Sierra Leone signed an agreement with China to build a new fishing harbor and fishmeal processing factory on a beach near a national park. Local organizations pushed for more transparency on the deal, which they said would harm the area’s biodiversity, according to a report by the Stimson Center, a foreign affairs think tank. In April 2022, Sierra Leone began purchasing land to build the harbor, despite opposition from locals who said their calls for the project to be relocated had been ignored.

In Argentina, China has provided billions of dollars in currency swaps over the last decade, providing a crucial lifeline amid skyrocketing domestic inflation and growing hesitancy from other international investors or lenders. China has also made or promised billion-dollar investments in Argentina’s railway system, hydroelectric dams, lithium mines and solar and wind power plants.

With this investment came political influence — which was in evidence back in 2016 after Argentine authorities sank the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10.

All 29 of the men on the Chinese jigger were rescued from the water that day. Most were scooped up by another Chinese fishing ship, Zhong Yuan Yu 11, and taken directly back to China. The captain and three other crew members, however, were rescued by the Argentine coast guard, brought to shore and charged with crimes including violating fishing laws, resisting arrest and endangering a coast guard vessel. They were placed under house arrest.

Roberto Wyn Hughes, a lawyer who frequently defends Chinese fishing companies, said that Argentine authorities typically have not prosecuted companies involved in illegal fishing and instead made them pay a fine before releasing the crew. The sinking of the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 could not be handled as discreetly, however, because it sparked a media storm in Argentina. Local news outlets described the attempted ramming by the Chinese and showed video of the sinking.

Hugo Sastre, the judge handling the case, initially justified the charges, saying that the Chinese officers had placed “both the life and property of the Chinese vessel itself and the personnel and ship of the Argentine Prefecture at risk.” But China’s Foreign Ministry pushed back. A spokesman told reporters that he had “serious concerns” about the sinking and that the Chinese government was engaged on behalf of the crew.

Three days later, the posture from the Argentine government began to shift. Susana Malcorra, Argentina’s foreign minister, told reporters that the charges had “provoked a reaction of great concern from the Chinese government,” adding, “We hope it will not impact bilateral relations.”

The Argentine judiciary also fell in line. “Given the doubt that weighs on the facts and criminal responsibility” of the captain, he and the three other sailors would be released without penalty, the court announced. Less than a month after the incident, the four crew members were flown back to China.

Typically about a quarter of the workers on fishing ships owned by the Chinese operating in Argentine waters are Chinese nationals, according to a review of about a dozen crew manifests published by local media. Jorge Frias, secretary general of the Argentine fishing captains’ union, explained that on Argentine-flagged ships, the Chinese call the shots. The captains are Argentines, but “fishing masters,” who are Chinese, decide where to go and when.

That was clear in April 2021, when Manuel Quiquinte, an Argentine crew member on a squid jigger called the Xin Shi Ji 89, contracted COVID at sea.

Owned by a Chinese company, the ship was flagged to Argentina and operating in Argentine waters. Its crew was a mix of Argentine and Chinese workers. Several days after Quiquinte fell ill, the Argentine captain called the Chinese owners to ask whether the ship could go to shore in Argentina to get medical care. Company officials said no and to keep fishing. Quiquinte died on the ship that May.

The captain was later charged with criminal neglect. In court filings, several of the ship’s Argentine crew members explained that despite Argentine law forbidding non-Argentines from being the captains or senior officers on these fishing ships, the reality is that the Chinese crew on board make the decisions. Even when they are designated on paper as lowly deckhands, the Chinese decide whether the ship will enter port to drop off a sick worker, such as Quiquinte. The Argentines might be designated as the engineers on board but they are not supposed to touch the machines when the vessel leaves port.

In his testimony, Fernando Daniel Marquez, the engineer on the Xin Shi Ji 89, summed up the power imbalance: “The only thing we do is to assume responsibility for any accident.”

This article was produced by the Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism organization in Washington. Maya Martin, Jake Conley, Joe Galvin, Susan Ryan, Austin Brush, Teresa Tomassoni and the Netherlands-based investigative collective Bellingcat contributed additional reporting.