- Share via

Rock concerts and auto races. Community festivals. Motocross championships that require an army of dump trucks hauling dirt.

Every time something other than football or soccer comes to the Coliseum, every time the carefully tended grass gets trampled or smothered or torn up, Scott Lupold feels uneasy.

“Plenty of sleepless nights,” Lupold says. “I’m a worrier by nature.”

As grounds manager at the stadium, Lupold is responsible for maintaining a pristine field. His venue isn’t the only one that must adapt to various configurations; consider how often Crypto.com Arena switches from basketball hardwood to hockey ice to floor seating for shows.

But, in the 100 years since it opened, the Coliseum has needed to learn a few tricks when it comes to morphing from standard turf to such unexpected surfaces as dirt, asphalt, ice and even snow.

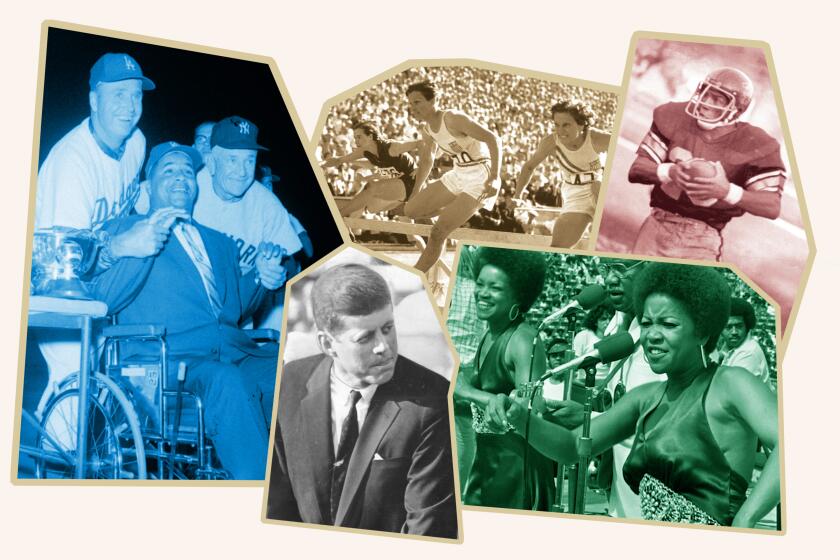

Highlights of some of the major events held during 100 years of the Los Angeles Coliseum, from sporting to political, cultural and specialty events.

“The Coliseum wasn’t built for just one purpose,” says Frank Guridy, a Columbia University professor who studies the civic impact of stadiums and arenas. “It’s a good, old-fashioned, single-tiered facility big enough to accommodate a bunch of different things.”

The stadium’s history of extreme makeovers dates back to its opening in 1923, the start of a long, trial-and-error process.

In the summer of 1936, a few years after the 1932 Summer Olympics, the Coliseum booked figure-skating champion Sonja Henie for a performance. Engineers laid coils across the field and used ice-making machines to create an 80-foot-long rink.

The refrigeration system proved no match for a blazing June sun and the show had to be canceled.

Another meteorological issue — torrential rains — delayed a planned ski jumping competition in the winter of 1938. The promoter built a 300-foot wooden ramp starting above the highest row of seats and swooping down toward the field. Snow-making machines laid a thin top-coating, then storm clouds blew in.

This time, however, the machines kept going and the weather cleared in time for the event to be held two nights later. Navigating a dangerously slick track, the famed Ruud brothers of Norway placed first and second in the Southern California Open Ski Jump.

When looking back at a myriad of events at the stadium, “there is a seduction of seeing it all through the lens of kitsch,” says William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. “The array is mind-boggling.”

Hollywood set designers helped the military create a South Pacific island on the stadium’s floor for a World War II rally. Roy Rogers held annual rodeos with film stars such as Hoot Gibson and Wild Bill Elliott.

In the late 1950s, the Dodgers made the Coliseum their temporary home with a fence erected across the grass and a laughably short, 250-foot left field.

The Superbowl of Motocross came along in the ‘70s as dump trucks rumbled down the tunnel where football players normally walk. More than 6,000 cubic yards of clay and decomposed granite were needed to form jumps, whoop-de-doos and banked turns.

The ¾-mile course snaked around the field, looped uphill through the peristyle arches and returned to the floor with a 150-foot, free-fall jump.

Given the hefty security deposit required, promoters tried protecting the turf with a variety of base layers — wood shavings, plywood, carpeting — none of which worked so well.

Over the past century, the Coliseum has been a cultural centerpiece for sprawling L.A., a place for sports, rock concerts, papal visits and even ski jumping.

“We laid plastic down over the grass but it ripped in several places and the Coliseum drains were plugged with dirt,” a promoter told The Los Angeles Times in 1974. “You know what plumbers cost.”

Years of trying to protect the playing surface eventually gave way to an entirely different approach.

Management was booking the venue more aggressively, leaving fewer open dates on the schedule. At the same time, the art of groundskeeping was growing more sophisticated.

Coliseum officials stopped attempting to heal the grass after races and concerts. Instead, they started ripping it out and starting from scratch, unrolling a new layer of sod that could be ready for play within days.

“The technology of re-sodding has changed so much,” Lupold says.

This new strategy allowed NASCAR engineers to cover the stadium’s floor with nearly 14,000 cubic yards of asphalt for a quarter-mile oval track last winter. It also put Lupold on the spot.

“Anything that’s going to be out there for any length of time, when coupled with a lot of weight … the turf is pretty much toast underneath,” he says.

At least the stock car race took place after football season. Seven months later, back-to-back shows by the industrial metal band Rammstein left only a few days to prepare for a USC game against Arizona State.

Concerts involve more than just a throng of fans standing around on the grass. Trucks drive on and off the field as workers build, then disassemble, the massive stage. Lupold plans ahead, visiting sod farms in Palm Springs and Coachella Valley every couple of months to be sure they will be ready when he needs them.

“We’ve got multiple fields being grown out there for different events,” he says. “We know what we’re getting and we know how to get it to a point where it’s ready to roll.”

Swapping the old stuff for new sod costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, an expense that is passed along to promoters. Short turnarounds require rolls of thicker, heavier sod at a higher price.

NASCAR teams have done what once seemed impossible, building a track inside L.A.’s Coliseum. This is how they did it and how drivers feel about it.

“We’ve done a lot of these things with concerts and replaced the field on really short windows,” Lupold says. “Knock on wood, we’ve been pretty good at pulling it off.”

Still, he doesn’t like using the word “routine” to describe the work. After the Rammstein concerts, his nerves didn’t settle until the Trojans and Sun Devils had played a few minutes.

No players slipped. Not great hunks of turf got yanked up.

“If you go back and look at those highlights … you wouldn’t be able to tell,” he says. But, he adds, “you’re going to worry about it as a groundskeeper.”