- Share via

Long before Chloe Kim became an Olympic champion and the face of women’s snowboarding, she was a star-struck little girl waiting for the chairlift at Mammoth Mountain.

The Southern California native recalls a day in 2009 when she found herself standing in line behind Kelly Clark, a pioneer in the sport. Clark remembers the moment too.

“She tugged on my sleeve and asked to go up the lift with me,” Clark says. “It was pretty cute.”

Ten years later, Clark has retired from halfpipe competition with a slew of medals from the Olympics, the X Games and World Cup competition. The 36-year-old now serves as an elder stateswoman for a new generation of riders.

Chief among her disciples is the 19-year-old Kim, the reigning champion from the 2018 Winter Games.

“She’s nothing but a huge inspiration to me,” Kim said before those Olympics. “I will always look up to her.”

To which Clark responded: “Hopefully my ceiling will be her floor.”

This link between snowboarding’s past and future is crucial if only because there weren’t as many female competitors to idolize when Clark began riding in the early 1990s. Growing up in Vermont, she recalls videotaping the 1998 Winter Games — “On VHS … remember that?” — and watching Ross Powers win bronze in the halfpipe.

Lilly King has been called brash, feisty and outspoken. But the reigning Olympic gold medalist in the 100-meter breaststroke sees it differently.

“Ross came from a town an hour from me,” she says. “I thought, ‘I could do that.’”

Her career would ultimately span nearly two decades, including three medals — a gold and two bronze — in five trips to the Olympics. In all, she accumulated victories in more than 70 career events.

“Kelly is a true legend,” U.S. Ski & Snowboard official Jeremy Forster says. “It’s as simple as that.”

But competitive results are not the full measure of her success, not in a sport that values lifestyle and a sense of camaraderie on the mountain, even among rivals. Around the midpoint of Clark’s career, after a bronze-medal performance at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, she paused to reflect.

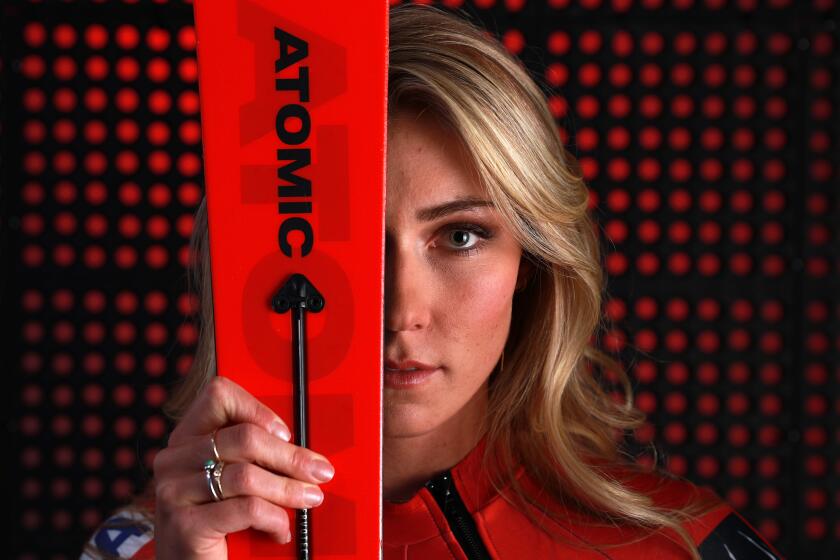

Mikaela Shiffrin used to feel uneasy about athletes speaking out on social issues, but her view has evolved as she secures her place as a skiing great.

Many of her peers were retiring, replaced by new faces in the rankings. She wondered whether this next wave might need — and be open to — guidance from someone who had been around for a while.

“If your dream only includes you, it’s too small a dream,” she says. “So I really embraced the idea of becoming a mentor.”

Kim was still young then — too young to compete at the 2014 Olympics where Clark captured yet another bronze — but the women became friends. Tricks and strategy were only part of what they discussed.

“Being a teenager, I’m always breaking down, like, I don’t know what to do with my life or this boy doesn’t like me,” Kim says. “It’s nice having someone like Kelly always giving me advice.”

Ogwumike began her involvement with the union as a player representative for her team

When Kim began to excel at the international level, when she nervously faced her first news conference, Clark sat beside her, saying: “You’ll be fine.”

It would not be long before Kim established herself as a unique talent, not unusually large or powerful but able to carry speed down the halfpipe, fueling unprecedented tricks.

In 2016, five years after Clark became the first woman to land a 1080 in competition, Kim set a new standard with back-to-back 1080s. In 2018, she became the first rider — male or female — to win four gold medals at the X Games before turning 18.

Her prowess is matched by an ebullient personality and social media know-how that has attracted legions of fans. It doesn’t hurt that, as a Korean American, she has brought more diversity to the halfpipe.

“I’m excited to see where she pushes herself,” Clark says. “And where she takes the sport.”

Snowboarding will have to wait patiently for what comes next because Kim has decided to put her career on hold for a season while attending Princeton University as a freshman. Getting accepted to the Ivy League school, and, perhaps, a broken ankle last spring, persuaded her to be “a normal kid for once.”

“It was a really tough decision to make because I love snowboarding so much and I love competing,” she says in a video message on YouTube. “But I’ve been doing it for my whole life pretty much.”

One of the few non-Californians on the U.S. women’s water polo team, she was a goalkeeper on the squad that won the 2015 world championship and the gold medal at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics.

The sabbatical won’t last long — Kim expects to resume training in May or June with an eye toward competing at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Clark can relate, if only because she remembers what it felt like to win gold as an 18-year-old at the 2002 Salt Lake City Games, that sense of reaching the pinnacle and wondering what to do next.

“I think it’s good for Chloe to figure out what she wants, what motivates her,” Clark says.

And if the young star needs advice, or maybe just wants to talk it out, there is always a veteran rider willing to listen.