Column: Is recall fever waning? Failure to take down Newsom reflects a broader pattern

- Share via

California had a recall election and it bummed people out.

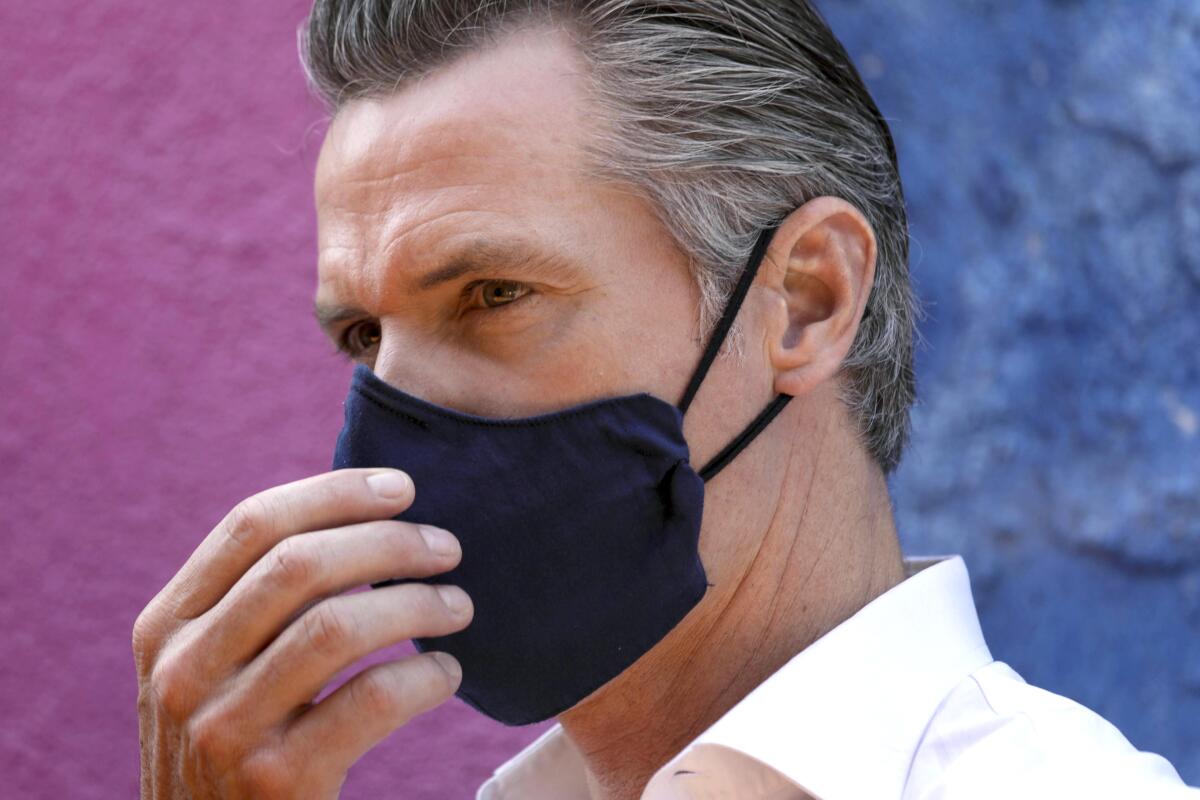

While COVID-19 raged and the forests burned, critics of Gov. Gavin Newsom waged a fruitless campaign to drive the Democrat from office less than a year before he was going to face voters anyway.

Up in smoke went more than $200 million in election costs. So too did any hope of Republicans seizing the governor’s office anytime soon. Newsom beat the recall in a landslide and emerged stronger than ever, making him a virtual shoo-in for a second term.

But at least Californians felt good about having that extracurricular opportunity to exercise their franchise, to shake up Sacramento and show the politicians who’s boss, did they not?

No, they did not.

The 1980 promise was about closing the gender gap, says top campaign strategist.

A new survey from the Public Policy Institute of California found nearly 4 in 10 likely voters said the recall effort made them feel worse about politics and elections, while just 18% said the campaign made them feel better. Those were probably the political strategists who made bank on millions of dollars in off-year advertising and consulting fees.

Not surprisingly, more Republicans (54%) expressed unhappiness with the state of political affairs than independents (41%) or Democrats (30%.) Fans of the San Francisco 49ers, who lost their shot at the Super Bowl to the Rams, can attest to that glum feeling when your side goes down to defeat.

But the not-insignificant number of dispirited Democrats suggests the reaction was more than just partisan grievance.

“There’s a sense that not everything is right with our recall system,” Mark Baldassare, president of the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute and director of its statewide poll, said after testifying this week at a legislative hearing on ways to overhaul the process.

Voters have concerns over how signatures are gathered to force a special election, the standards for removing an officeholder and the rules surrounding replacement candidates, which allow someone with marginal support to take office should a recall succeed. And, Baldassare said, there was concern “going forward. ... Are we going to live in a world in which this is our future?”

It’s not hard to imagine one costly and distracting recall campaign after another, especially with the nation’s whiner in chief — that would be ex-President Trump — setting a daily example of how to lose badly and undermine election integrity.

But there are positive signs that recall fever may be waning somewhat.

A militia-backed effort to oust a Republican Shasta County supervisor appears headed for success after Tuesday’s election, and San Franciscans may soon remove three flaming lefties from the city’s school board.

Those instances, however, may be the exception to a recent nationwide pattern in which more recall attempts failed than succeeded. That’s the first time that has happened since Joshua Spivak, a blogger and one-man clearinghouse on recall politics, began tracking such elections a decade ago.

Typically, about a quarter to a third of recall attempts reach the ballot. Of those, 60% result in removal of a targeted officeholder, according to Spivak’s research. Another 6% of those beleaguered lawmakers resign.

But in 2021, in what Spivak called “the big flop,” only 66 of 609 attempts reached the ballot. And just 26 lawmakers were removed from office.

Most of the efforts were rooted in opposition to coronavirus-related restrictions, such as lockdowns and mask mandates.

“The results, as can be seen by both the failure to get signatures and the failure to actually win elections, [may be] viewed as effectively an endorsement of the restrictions,” Spivak wrote on his blog.

Ranked-choice voting is an effort to reduce political polarization. Let’s see if it works.

In California, voters have long had an ambivalent relationship with the notion of direct democracy and, for that matter, their elected officials.

The initiative, referendum and recall were all birthed about a century ago as part of the Progressive movement, which sought to rein in the special interests running roughshod over Sacramento by handing voters the tools to pass laws, override lawmakers and oust them between regular elections if they choose.

Many appreciate the do-it-yourself approach to government, at least some of the time. But there is also an undercurrent of annoyance if voters are summoned too often to the polls, as in why am I being asked to do the work lawmakers are supposed to do?

“Californians are happy to take matters in their own hands. That’s the state’s libertarian streak,” said Darry Sragow, a veteran California campaign strategist. But at the same time, “People want to be left alone to just live their lives.”

There was a time, starting in 2002, when — between a recall, a special election and the regular campaign calendar — California held elections for several years running. Voter fatigue became a thing.

Recalls should be reserved for instances of corruption or malfeasance in which prosecutors fail to act, or law-breaking officeholders refuse to step aside. They shouldn’t become a way to short-circuit the political process simply because the losing side doesn’t like the outcome of an election, or someone from the other party holds office.

If last year’s failed effort has given California voters second thoughts about the recall and makes it less likely we go through another costly and time-wasting campaign exercise, that’s a positive development.

One election every two years is plenty.