Column: With $276 million down the drain, it’s time to revamp the California recall

- Share via

Well, that was a complete and utter waste.

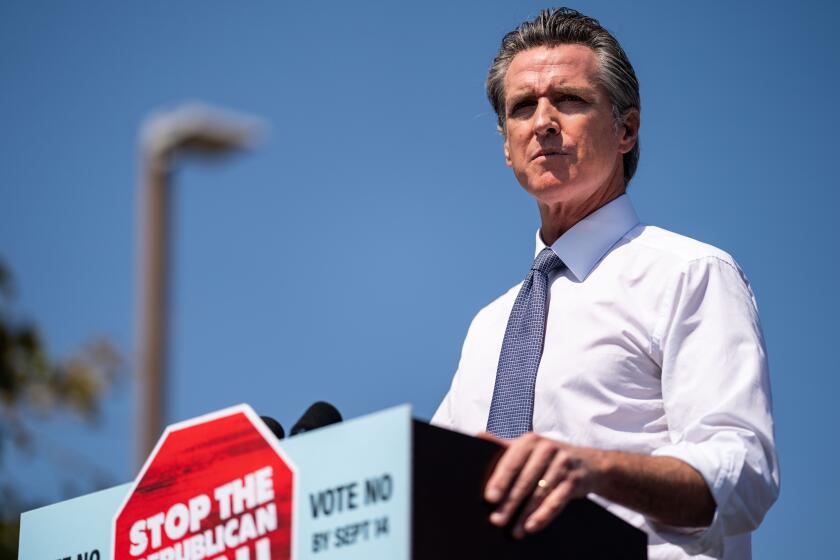

Now that the recall election is over and voters have soundly rejected the effort to give Gov. Gavin Newsom the boot, the exercise should be recognized for what it was: an act of partisan petulance that took California taxpayers for a ride.

Or, put another way, a hugely expensive effort by outnumbered Republicans and their allies to commandeer an office they couldn’t win under normal circumstances.

That’s not a defense of Newsom, who is hardly beyond reproach. You may object to his herky-jerky handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, lay blame for the state’s fraud-riddled unemployment system at his feet, deplore his moratorium on the death penalty, or hate his gelled hair and perfect teeth.

Not to worry. In less than nine months, California voters will have a chance — once again — to render their verdict on the Democratic incumbent and his policies, along with his toothpaste smile. There is an election in June 2022, right on schedule, when Newsom is expected to seek a second term.

After Tuesday’s blowout, he’s a prohibitive favorite to win both the top-two primary and the November runoff.

The election provided California voters an opportunity to judge Gov. Gavin Newsom’s ability to lead the state through the COVID-19 pandemic, a worldwide health crisis that has shattered families and livelihoods.

Critics of the governor insisted his malpractice turned the state into such a cesspit that only his immediate removal would do, hence the need to short-circuit the regular election process. Each passing day, they suggested, only compounded the disaster.

And yet some of those same Newsom critics objected when the governor’s Democratic allies — seeking an advantage — cleared the way for the election to take place Sept. 14, rather than waiting several more weeks to vote.

So much for urgency.

The cost of the special election was in the neighborhood of $276 million.

Here are several ways the money could have been better spent:

• Paying the state’s share to educate 28,000 kindergarten through 12th-grade students.

Or ...

• Funding 58,000 middle-class scholarships for UC and Cal State students, as well as educating nearly 12,000 K-12 students.

Or ...

• Providing just under half of the money budgeted this year to fight California’s abundant wildfires.

So much for the wise use of taxpayer dollars.

Every California governor since 1960 has faced multiple recall attempts; the threat of early eviction comes with the office, along with a security detail and the chance to show up at natural disasters in spiffy outerwear. In the case of Newsom — who walloped one of his recall opponents, Republican John Cox, in a November 2018 landslide — talk of a recall began even before he was sworn into office.

So much for waiting and seeing.

Some argue that gubernatorial recall elections are a rarity, given the fact there have been just four in all of U.S. history. But two of those have occurred in California, less than two decades apart.

Clearly, something has changed as the state’s 1911 recall provision is harnessed to 21st century technology.

Richly funded petition drives and the growth of the political-industrial outrage complex, stoked by social media and the pyromaniacs flinging matches on talk radio, have greatly enhanced the odds that partisan discontents — I don’t like the governor’s personality, I don’t like his policies, I don’t like the fact he belongs to a different party — will lead to elections like the one Tuesday.

Add to that an increasing refusal to accept election outcomes — a recklessness fed by the cavalier former President Trump and others parroting his phony claims of voter fraud — and it’s easy to see how recalls could go from being a rarity to a regular feature of California politics.

That’s why it’s time for a reset.

There are 19 states that allow their governor to be recalled. California is by far the most permissive.

It takes signatures reflecting just 12% of the ballots cast in the prior gubernatorial contest to force an election. In Newsom’s case, that meant proponents needed to collect just under 1.5 million signatures in a state with more than 22 million voters and nearly 40 million residents. That may sound like a lot. But it’s not in this age of pugilistic partisanship and unceasing political warfare.

The threshold needs to be higher, and the reason for a recall needs to be more serious, such as proof of corruption or malfeasance, or conviction for a serious crime.

Once a recall makes the ballot, the rules are even more perverse and less democratic.

A targeted governor can receive 49.9% of the vote in favor of serving out his term, and be replaced by a candidate receiving just a small fraction of that support. As it stands, the top vote-getter automatically becomes governor, which in a multi-candidate field could mean taking office with 20% support or even much less.

A better system would be a runoff between the two top finishers; that way at least one of them would have the backing of a majority of California voters.

The campaign is over. And what Gov. Gavin Newsom takes from what happened — what he does or doesn’t learn from it — will affect millions of Californians.

The petition that led to Tuesday’s election presented a litany of complaints: about immigration, capital punishment, homelessness, taxes, water use. There was conspicuously no mention of COVID-19, which helped drive the recall effort and, in the end, gave Newsom a powerful weapon to fight back. (Does California, he asked, want to become a pandemic death trap like Florida and Texas?)

The hodgepodge of grievances brings to mind a scene from the 1953 movie “The Wild One,” about a gang of motorcycle toughs who invade a small California town. “What are you rebelling against?” the leader, played by Marlon Brando, is asked. “Whaddaya got?” he famously replies.

That’s just the sort of heedless, reflexive hostility that helped bring about Tuesday’s election: It was anger in search of an outlet, frustration seeking release, the losing side pursuing vengeance after years of political futility.

The state shouldn’t ever again have to squander money on an extraneous election like the one California just experienced. A quarter of a billion dollars is too much to spend on another backdoor attempt to seize the governor’s office.