Diego Maradona, Argentine soccer legend, dies at 60

Diego Maradona, who led Argentina to victory in the 1986 World Cup but was tormented by drug abuse in his later years, has died. He was 60.

A mop-haired boy from a Buenos Aires slum, Diego Armando Maradona dribbled and dazzled his way to world fame, becoming one of the greatest soccer players of all time and achieving a godlike status in his homeland when he led Argentina to victory in the 1986 World Cup.

But he also was one of the most self-destructive, a volatile man of prodigious appetites whose excesses landed him in the hospital again and again.

Never far from the spotlight he chased with such fury, Maradona died Wednesday of a heart attack, the Associated Press confirmed. He was 60.

Maradona had been plagued by health issues in recent years, and was recently released from a Buenos Aires hospital after suffering a subdural hematoma, which required brain surgery.

As the news of Maradona’s death circulated around the world Wednesday, Argentine President Alberto Fernandez called for three days of national mourning, while UEFA, soccer’s governing body in Europe, announced there would be a minute of silence before its Champions League and Europa League games this week.

Soccer stars past and present took to social media to say goodbye.

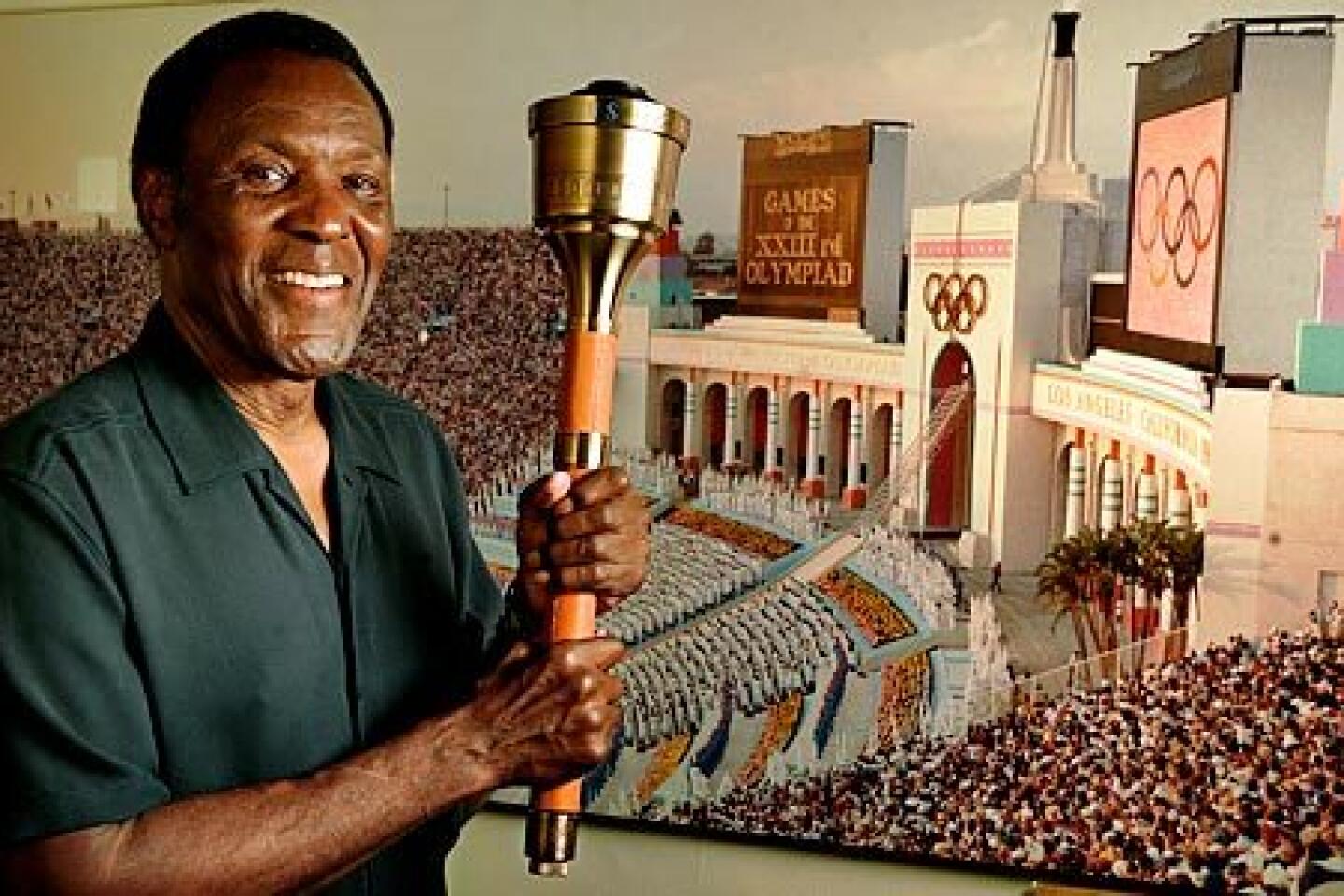

Pelé, the Brazilian legend and perhaps the greatest player of all time, wrote on Twitter that he has “lost a great friend and the world lost a legend. … One day, I hope we can play ball together in the sky.”

Cristiano Ronaldo, the five-time world player of the year from Portugal who currently stars for Italy’s Juventus, tweeted, “Today I say goodbye to a friend and the world says goodbye to an eternal genius.”.

Like that other famous Argentine export, the tango, Maradona brought flair, passion and an undeniable sense of darkness to his sport and his life. On the field, few could match his artistry, skill and creativity.

During a professional career that began on a Buenos Aires field when he was 15, Maradona scored hundreds of goals, many of them the stuff of legend, including two in a single match against England in the 1986 World Cup. The first is considered by many the most notorious goal in the history of the sport, and the second among the most celebrated.

He went on to lead Argentina’s national team to the World Cup title in that tournament, the summit of his career. But drug abuse and other acts of self-destruction tainted his final years as a player and he retired in 1997, just a whisper of his former self.

Maradona played 91 games for the Argentine national team and was a star for teams in Italy and Spain. He played his last World Cup game in Foxboro, Mass., in 1994, escorted off the field for a drug test he would fail.

One of eight children of a laborer who had migrated to the city from rural Corrientes province, Maradona was born Oct. 30, 1960, in a villa miseria, or slum, in the suburban Buenos Aires community of Villa Fiorito. The family lived in abject poverty.

In his autobiography, “I Am El Diego,” he recalled walking to school kicking a ball along streets, up stairs and along railroad tracks. He spent hours playing pickup games in a nearby horse pasture.

When he was 9, a friend invited him to a tryout at the Argentinos Juniors, an adult professional soccer team. He impressed enough to earn a spot on the Cebollitas, or Little Onions, a feeder club for the team.

The Little Onions would go on to win 136 games without defeat, with young Maradona often scoring three or more goals a game.

By the time he was 12, he was working at professional games as a ball boy, becoming a favorite of the crowds for his halftime juggling skills. A television variety show invited him to show off his talents, and in soccer-mad Argentina he became a minor celebrity.

Just a few days before his 16th birthday, the coach of Argentinos Juniors brought him onto the first team. He first stepped onto the field as a substitute, with the coach telling him, “Go, Diego, and play like you know how to play. And if you can, dribble through someone’s legs.” Minutes later, the young Maradona did just that.

“That day,” he said later in his autobiography, “I felt like I touched heaven with my hands.”

Leading Argentine teams began a bidding war for his services. He moved his family out of Villa Fiorito to an apartment. Eventually, he joined the famed Boca Juniors team.

He was first named to Argentina’s national team in 1977, when he was 16. But coach Cesar Luis Menotti failed to name him to the squad that won the 1978 World Cup, which Argentina hosted. Maradona was crushed.

“I knew he was a great player, who was going to have the chance to play in many more World Cups,” Menotti would say years afterward.

In 1982, after leading Boca Juniors to a league championship, Maradona signed with the Spanish club Barcelona. It was there, friends say, that he got his first taste of cocaine.

“I was, I am now, and I have always been a drug addict,” he would acknowledge years later.

But on the field, his powers only seemed to grow. After fighting repeatedly with Barcelona management, he moved to the Italian club Napoli, scoring a series of remarkable goals that quickly endeared him to the notoriously fickle Italian fans.

In the 1986 World Cup, played in Mexico, the full range of his skills was on display. During the tournament he scored five goals in leading Argentina to its second World Cup victory, but he will always be remembered for the two he scored in a quarterfinal match against England. Passions were high for the game, played just four years after Britain defeated Argentina in the Falklands War.

With the game scoreless, Maradona rose up and challenged the English goalkeeper Peter Shilton for a high pass. Maradona punched the ball with his fist into the goal, a blatant violation of the rules seen by nearly everyone on the field but the referee.

Asked afterward if he had used his hand, Maradona said the goal had been scored “by the hand of God.”

Diego Maradona’s “Hand of God’ goal against England in the 1986 World Cup championship game.

Five minutes later, Maradona scored another, the decisive goal in what would be a 2-1 victory over England. Taking the ball in his own half of the field, he dribbled and weaved past most of the English team, then tumbled to the ground as he fired a shot that beat Shilton. In a poll conducted two decades later by soccer’s international governing body, FIFA, it was selected the greatest goal in the history of the World Cup.

“Today he scored one of the most brilliant goals you will ever see,” English coach Bobby Robson said after the game. “The first goal was dubious. The second goal was a miracle.”

Maradona recalled in his autobiography: “It was as if we had beaten a country, more than just a soccer team.”

A week later, when Argentina defeated West Germany 3-2 in the championship game, he stormed off the field and into the locker room shouting obscenities; for Maradona, victory was always tinged with the lingering anger he felt for his rivals and detractors.

Still at the peak of his powers, he inspired Napoli to its first Italian league titles in 1987 and 1990. He married childhood sweetheart Claudia Villafañe in 1989, but would admit later to being unfaithful to her. In 1991 he was suspended for 15 months after testing positive for cocaine.

Noticeably overweight, he went on a crash diet before the 1994 World Cup, hosted by the United States. But after scoring two goals in three games, he failed a drug test for ephedrine, a performance-enhancing drug. He was kicked out of the World Cup and banned from the sport for 15 months.

“My soul is broken,” Maradona said. But he blamed FIFA officials more than himself. “They cut my legs out from me just as I was trying to come back.”

Maradona eventually returned to play for his old Argentine club team, Boca Juniors, where he retired in 1997.

Away from the pitch, Maradona seemed a sad, rotund figure. He traveled to Cuba to seek treatment for drug abuse in 2002 and eventually struck up a friendship with Fidel Castro. When he returned to Argentina, he sported a prominent tattoo on his arm of the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara, one of Castro’s top lieutenants during the Cuban revolution.

Shortly after his 2004 divorce, Maradona began another downward spiral and was hospitalized after a drug overdose and then again for alcohol poisoning. His family had him hospitalized in a psychiatric facility after he threatened to leave the intensive care unit where he had been receiving treatment. He was released but returned a few days later after a bout of overeating. His death seemed so imminent that daily newspapers in Buenos Aires prepared special sections to run with his obituary.

But after a few weeks he was released and went on to host a popular variety show on Argentine television, “Night With No. 10.” And throughout his career, he never seemed to forget where he came from, lending his name and profile to dozens of charitable endeavors that raised millions, mostly for children’s causes.

He coached briefly, and erratically, for two teams in the Argentine league and then, in a move that both stunned and delighted the nation, in 2008 was handed the reins of the country’s national team, which was struggling to right itself before the World Cup. The team advanced to the quarterfinals, hoping that new superstar Lionel Messi’s sublime soccer skills would overcome the confounding coaching decisions made by Maradona. He was dismissed in 2010.

In 2018, Maradona — whose gait had turned to a shuffle and once crisp voice to a mumble — was hired to coach the Dorados, a professional team based in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, in the heart of drug country. The only person more famous than Maradona in Sinaloa was Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the legendary drug kingpin.

“Taking Maradona to Sinaloa is like taking a kid to Disneyland,” sportswriter Rafael Martinez wrote on Twitter.

But Maradona, silencing critics again, made it work. Hobbled by knee injuries and using a cane as he shuffled about, Maradona managed to take a young team buried deep in Mexico’s second division to the playoff final, where it lost by a goal in overtime.

“He is very happy, very satisfied with his work,” said Fox Deportes analyst Daniel Brailovsky, a former teammate. “It’s his passion, it’s his life. It’s everything for him.

“Maradona can’t live without football, and football can’t live without Maradona.”

Six months later he left Mexico, quickly resurfacing in Argentina as manager for the Gimnasia de la Plata club.

His cinematic life was captured in the 2019 HBO documentary “Diego Maradona,” with filmmaker Asif Kapadia combing through 500 hours of never-before-seen footage. The result portrays Maradona as he was: a man both tortured and talented, a superhero, antihero and villain who was brilliantly gifted on the field and maddeningly troubled away from it.

“Maradona is the synthesis of Argentina,” suggested Guillermo Oliveta, president of the Argentina Marketing Assn. “He came from dire poverty and went up so quickly in social status. And then he crashed, just like the country.”

Tobar is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writers Kevin Baxter and Steve Marble contributed to this report.