Animation by Tomasz Czajka / For The Times; Los Angeles Times photo illustrations; photographs by Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times, Raul Roa, Getty Images, Associated Press and AFP

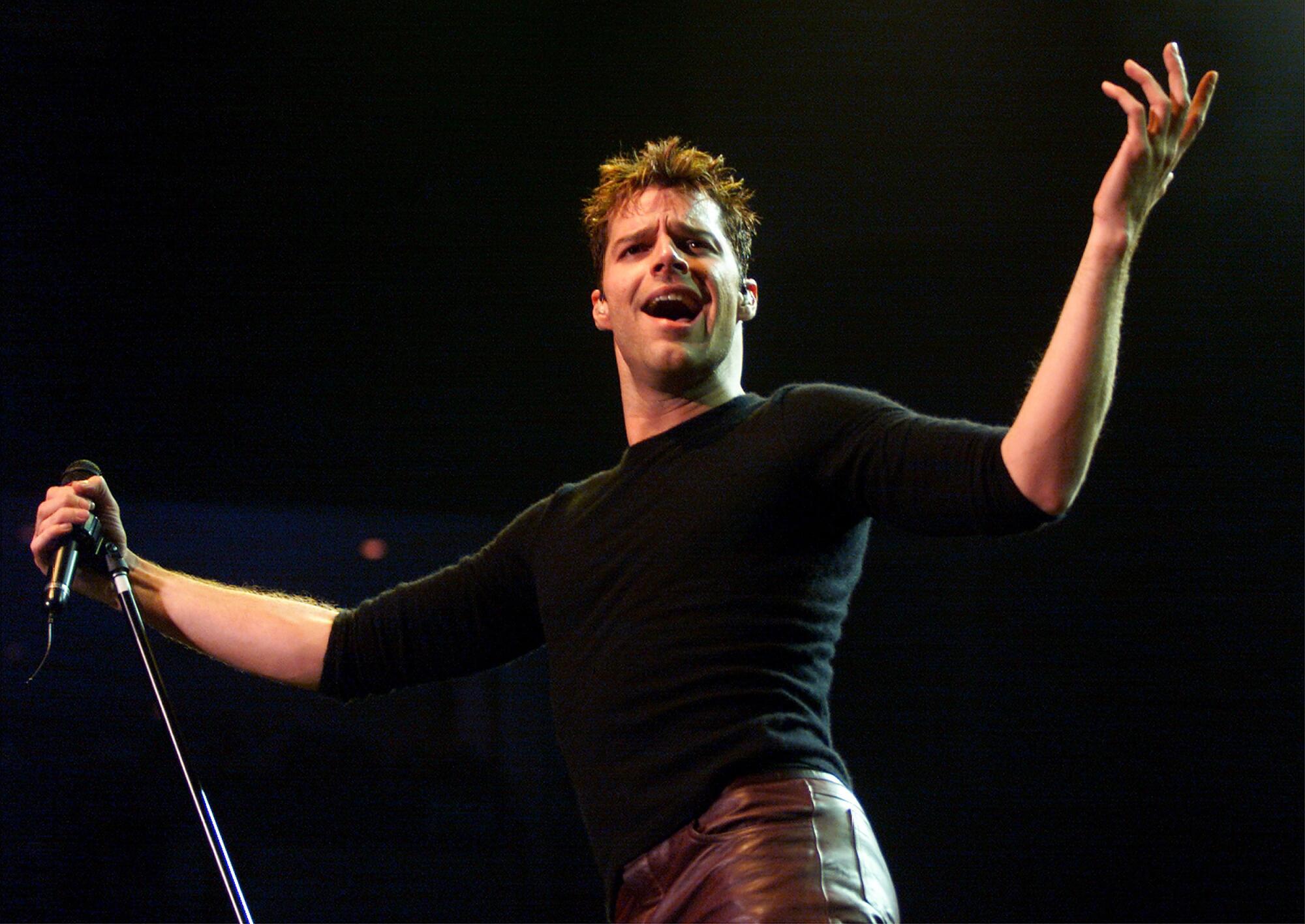

Ricky Martin knew “Livin’ La Vida Loca” would be an instant hit when producer Desmond Child and songwriter (and fellow Menudo alum) Robi “Draco” Rosa brought him a demo of the track.

The Puerto Rican singer and his team were putting the finishing touches on “Ricky Martin,” his fifth studio album and first ever in English, when he heard what would become the LP’s first single.

“I said, ‘Hold on a second, wait a minute, this is the song,’” Martin recently said on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.”

“The album was already recorded. We were about to go into mastering and I said, ‘Everybody go back into the studio. We need to record this song.’”

Talk about a premonition.

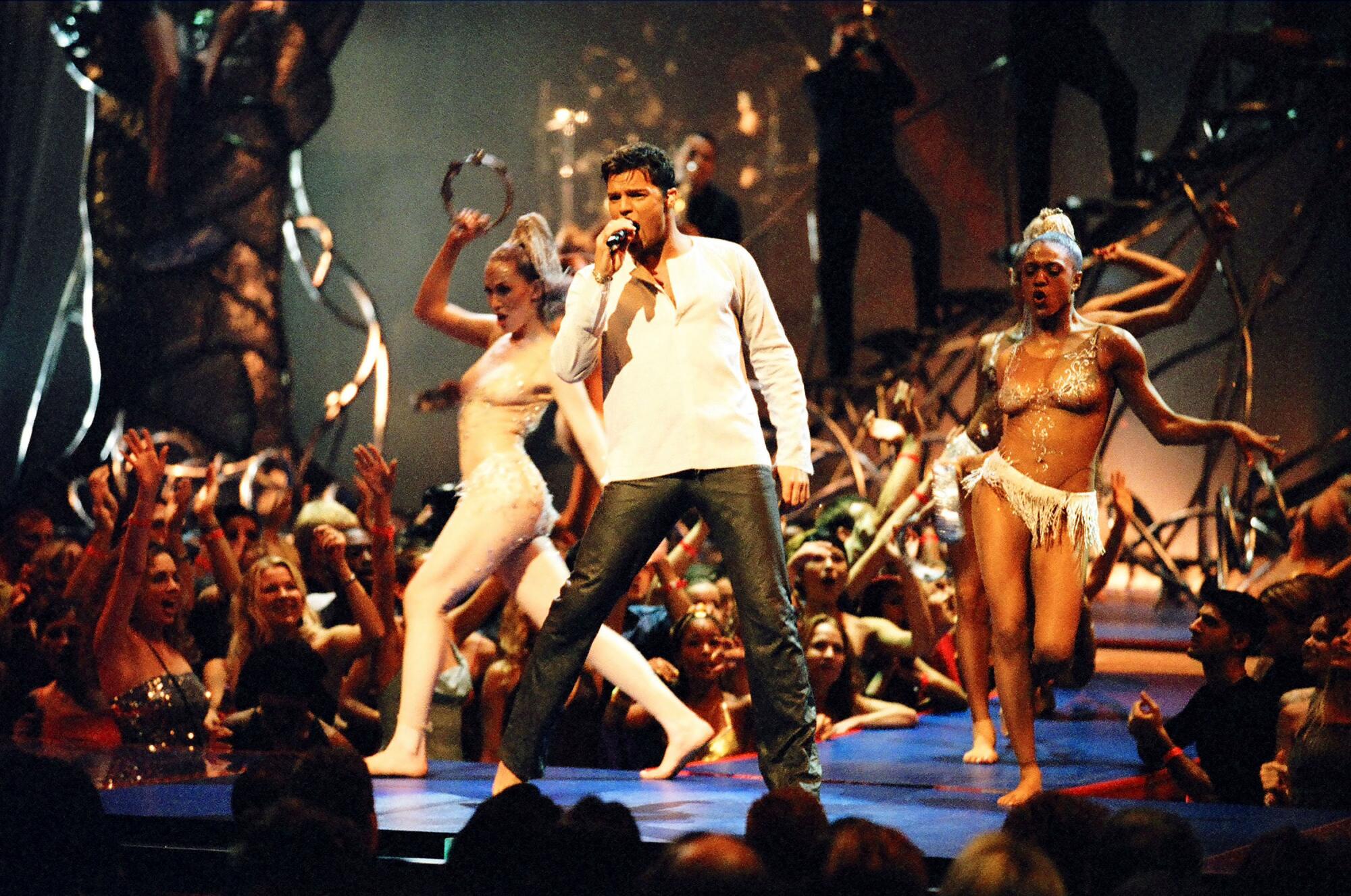

“Livin’ La Vida Loca,” a ska-infused, fast-paced earworm about a seductive, sinister woman living on the edge, was released on March 27, 1999. It immediately took over Top 40 radio and topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart weeks later. The music video, an expensive production full of sex appeal, was on constant rotation on MTV.

The 1999 Project

All year we’ll be marking the 25th anniversary of pop culture milestones that remade the world as we knew it then and created the world we live in now. Welcome to The 1999 Project, from the Los Angeles Times.

“Not for a very long time have we seen a new artist with the star power of Ricky Martin,” Tom Calderone, then-chief of programming at the cable network, told The Times in 1999. “We played his video, and the next day it was among the most requested… for a brand new artist to catapult to the top like that, we just don’t see that.”

Martin, who began his artistic trajectory by acting in commercials in Puerto Rico when he was 9, was now 27 and all over American network television, wowing audiences in studio and across the country with his energetic and polished performances on programs like “Today,” “The Tonight Show With Jay Leno” and even “Saturday Night Live.”

“Let me tell you something, America is in love with you,” Rosie O’Donnell told the pop star when he appeared on her daytime talk show on May 11, the same day as the release of “Ricky Martin.” The album would debut at No. 1.

In the interview, O’Donnell said she learned about her guest the previous year during a conversation with Tommy Mottola in which Sony Music Entertainment’s then-chief executive (and her friend) predicted that Martin would be the biggest star in the world. In fact, he was betting on it — Martin was signed to Columbia Records, a subsidiary of Sony.

“I said, ‘Who’s Ricky Martin?’ No offense, but I didn’t know,” O’Donnell said.

By summer 1999, Mottola’s prediction had turned true. Martin would become a household name in the United States, sharing the top of the charts with the likes of the Backstreet Boys, TLC and Britney Spears. He would also be the face of the so-called Latin explosion in pop music, a phenomenon that ended up being more marketing ploy than demographic eventuality.

Although the instant ubiquity of “Livin’ La Vida Loca” might suggest otherwise, Martin’s success did not come overnight.

By the time the song hit the airwaves, Martin had spent his teenage years touring the world as a member of the boy band Menudo; earned heartthrob status after acting in a telenovela (“Alcanzar una Estrella II”), a U.S. soap opera (ABC’s “General Hospital”) and on Broadway (“Les Miserables”); and dominated the Latin American music charts with his four previous Spanish language albums, which sold millions of copies. Such was his popularity that FIFA, the International Assn. of World Football, asked Martin and his team to create the theme song for the 1998 World Cup. The end result was “La Copa de la Vida,” an infectious samba-inspired banger that became a global hit.

If anyone was primed to become a major pop star in the United States, it was Martin.

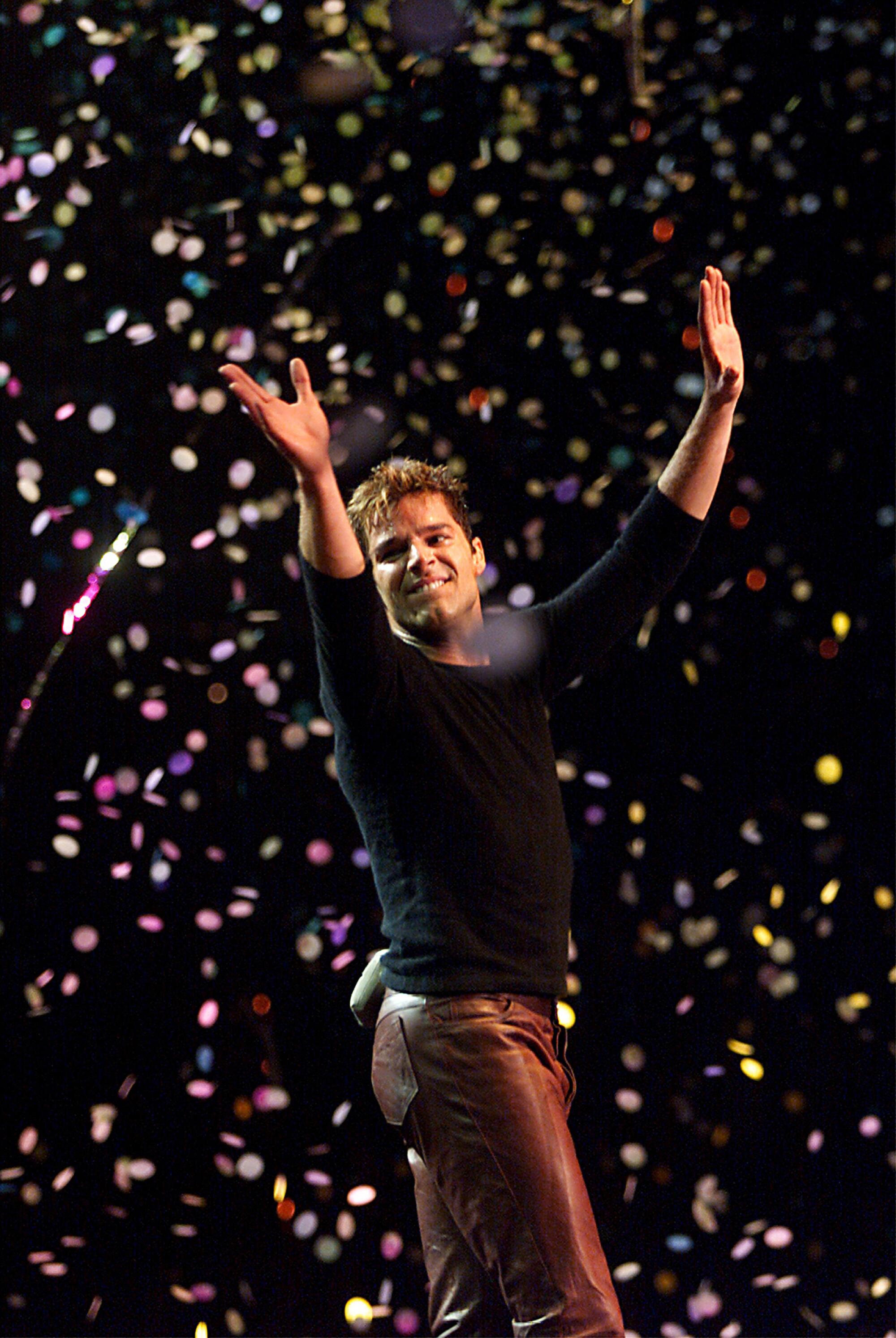

His chance to win over an English-speaking music audience would come on Feb. 19, 1999. After some arm-twisting by Mottola, the Recording Academy invited Martin to perform at the 41st Grammy Awards.

“We had enormous leverage at that time with almost every major superstar on our label,” Mottola told Billboard in 2019. “We heavily voiced our ‘opinion and influence and said, ‘Ricky must have a performance on the Grammys.’ No was not an option.”

Martin did not disappoint, receiving a standing ovation from the audience at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles after electrifying attendees with an English rendition of his World Cup hit that featured plenty of horns and drums. Madonna was so blown away by the Puerto Rican pop star that she was seen clinging to him backstage — by this time, the Material Girl had agreed to record a track with Martin for his upcoming English debut.

(As a side note, the 1999 awards show was also historically significant because it is where the Recording Academy announced creation of the Latin Grammys.)

All of a sudden, everybody wanted a piece of Martin, and the fanfare that followed his Grammy performance all but ensured that “Livin’ La Vida Loca” would debut with a bang — the single would sell more than half a million copies in the U.S. alone within a matter of weeks.

That momentum propelled Martin’s eponymous album to the top of the Billboard 200 after its release, selling 661,000 copies in its first week (by the year’s end, “Ricky Martin” would sell 6 million copies, making it the third bestselling album of 1999, behind the Backstreet Boys’ “Millennium” and Britney Spears’ debut, “...Baby One More Time”). As The Times reported, fans waited hours in line at the Virgin Music Store in West Hollywood to be among the first people to buy the album at midnight.

The store was also giving away free tickets to the KIIS-FM Wango Tango concert later that summer at Dodger Stadium — a show that is engraved forever in radio host Rick Dees’ memory.

“I’ve never heard screams like that,” Dees said, recounting the moment he introduced Martin to the crowd. “I didn’t even get to the ‘Mar’ part of Martin.”

Dees, known for his internationally syndicated show “The Rick Dees Weekly Top 40 Countdown,” remembers Martin from his Menudo days.

“He [would] come in and had a glistening tooth smile. He just seemed so happy. It was infectious,” he said, adding that Martin “had the look of a superstar.” He remembers blasting “Livin’ La Vida Loca” on huge Altec Lansing speakers when Martin came to the L.A.-based studio.

“It was the first time he’d ever heard it go out over the speakers at a radio station, and he was giggling and he started dancing and jumping up and down,” Dees said. “It looked like he had swallowed a jackhammer.”

L.A. Times photo editor Raul Roa, who shot many of the up-and-coming Latin stars as a freelance photographer, remembers the Martin craze like it was yesterday.

“You could just feel the electricity in the air,” Roa said, “People were dying to get backstage [to see Martin]. They would offer to buy my photo pass from me.”

But what made Martin such a draw? Besides his work ethic, talent and “I can’t believe this is my life” approach to his success, the star also filled a void in the broader pop music landscape.

In an April 1999 Times story, Jody Gerson, then vice president of EMI publishing (and now chief executive of Universal Music Publishing Group), argued that the industry lacked a single male figurehead to contrast with the choreographed look and feel of boy bands like NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys, adding that consumers were tired of “depressing alternative bands” and wanted “happy music you can dance to.”

“These Latin artists look at you, and you feel like they could fall in love with you,” Gerson said.

In the media frenzy that followed the release of “Livin’ La Vida Loca” and Martin’s English language LP, the performer’s ethnicity became a central part of the coverage. His success was seen as a harbinger of a new wave of artists with roots in Latin America ready to take over the charts. America, it seemed, was ready to embrace Latinos — then about 11% of the U.S. population, or approximately 30 million people — and their culture.

“Latin-tinged pop is blowing up because it fits the musical times,” journalist Christopher John Farley wrote in a Time magazine cover story.

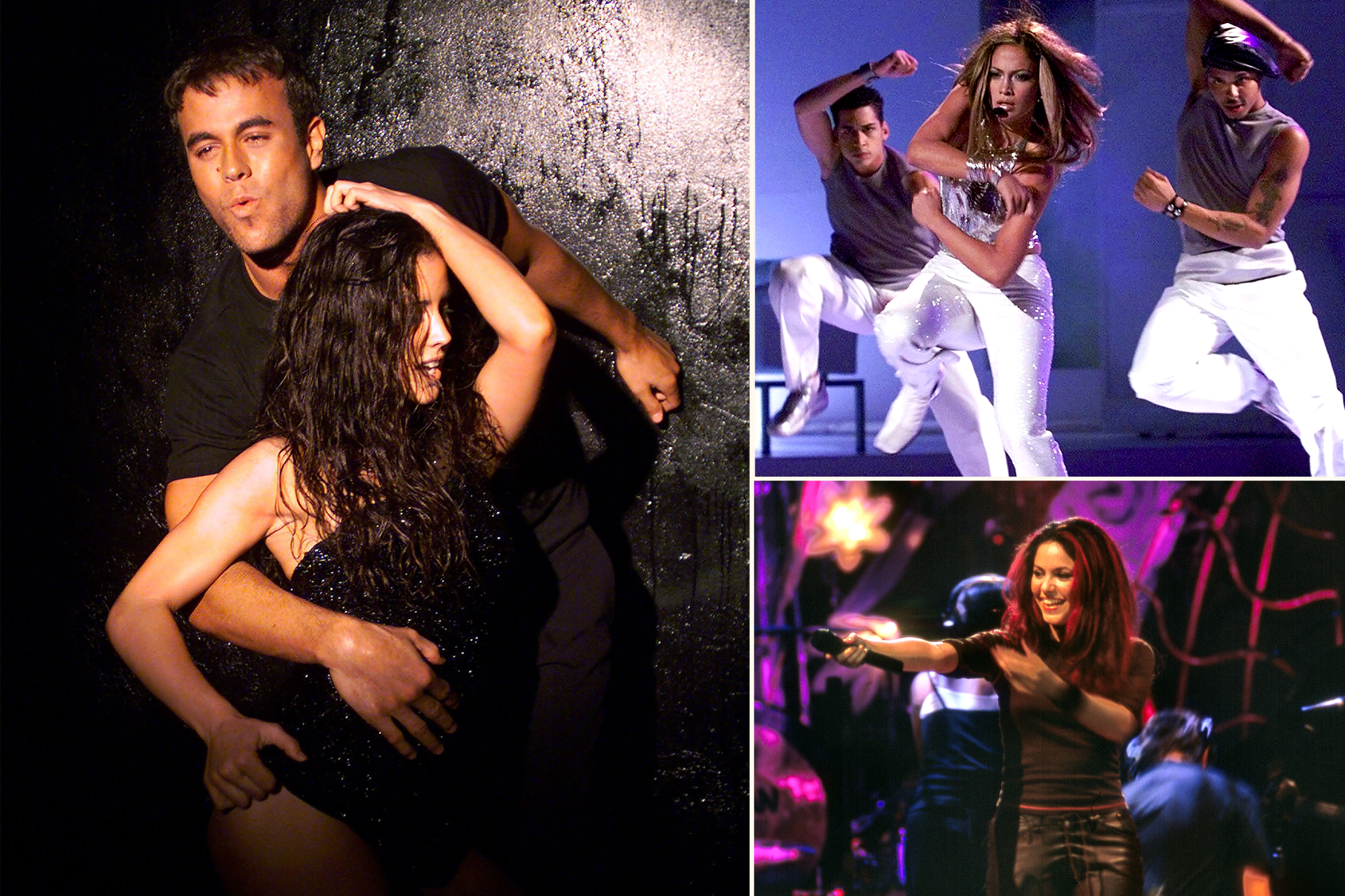

Indeed, 1999 was a big year for artists with Latin American roots. Following in Martin’s heels with English language albums were Ecuadorian American Christina Aguilera (“Christina Aguilera”), as well as Nuyorican artists Jennifer Lopez (“On the 6”) and Marc Anthony (“Marc Anthony”). Legendary rocker Carlos Santana was also lumped in with this group thanks to the release of “Supernatural.” As was Enrique Iglesias (“Enrique”) — never mind that the crooner was born in Spain.

Two years later, Shakira, then considered to be the Colombian version of Alanis Morissette, would follow with the release of “Laundry Service,” her first LP in English.

Further reading from our archives

The Los Angeles Times extensively covered the rise of Ricky Martin and “Livin’ La Vida Loca” in 1999. Here’s a selection of stories from our archives.

Not every journalist bought into the Latin explosion narrative. Times reporter Alisa Valdes-Rodriguez and music columnist Agustin Gurza actively challenged it, arguing that the storyline was reductive and lazy.

“While no one denies that focusing the mainstream media spotlight on Latino musicians and singers is overdue, the recent storm of coverage has exposed an abysmal ignorance about the complexity, diversity and reality of Latinos and Latin music,” Valdes-Rodriguez wrote in June 1999.

“Lost in the recent frenzy to cover ‘crossover’ artists have been two simple facts: Latino artists do not necessarily perform in Latin music genres; and Latin music is not always performed by Latinos.”

Similarly, Gurza countered the notion that the rise of Martin signaled America’s willingness to accept Latin music.

“The American pop mainstream finds it hard to accept other cultures on their own terms,” he argued. “The outside artist must almost always conform to American tastes or be marginalized. Music must pass through a mass-market blender, filtering out ethnic character and foreign meanings.”

It’s a valid point — save for the three words in its title, the lyrics of “Livin’ La Vida Loca” are entirely in English, and although the song sounds like it’s Latin-infused, it contains no elements that are staples in Latin music.

“But it’s a one-way deal,” added Gurza. “Latin American audiences have always embraced U.S. artists, culturally intact and in English.”

It wouldn’t take long for Valdes-Rodriguez and Gurza to be proved right. By 2004, the steady stream of artists with Latin American heritage breaking into mainstream pop had all but disappeared, prompting Gurza to dub the “Latin explosion” as nothing more than a “marketing mirage” orchestrated by Mottola. With the exception of Iglesias, who was signed to Interscope, every Latino artist that saw their careers take off in 1999 was signed to a label owned by Sony.

Mottola himself would admit the charge.

“There never really was a Latin explosion,” he said in a Billboard interview, “But we used it to take gigantic advantage of it, and lots of our stars benefited from that.”

Twenty-five years later, Valdes-Rodriguez looks back at the “Livin’ La Vida Loca” craze as a “bittersweet moment” for Latin music.

“On the one hand, I was glad that people in the mainstream were kind of waking up to the fact that there was this whole other U.S.-based music industry that was huge,” she said. “But on the other, it was a little bit frustrating because every 10 years, the mainstream corporate media will be like ‘Latinos are exploding’.”

Valdes-Rodriguez, who left journalism to pursue a literary career, says that just about every decade in the 20th century presented its own Latino “crossover” figure.

In the 1950s, it was Ritchie Valens with “La Bamba.” The 1980s had Gloria Estefan and the Miami Sound Machine. Less than five years before “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” Tejana superstar Selena Quintanilla was poised to take over the mainstream before she was killed in 1995.

“What’s frustrating is that every time someone like [Ricky Martin] comes along, there’s this collective erasure in the mainstream press of those who came before,” Valdes-Rodriguez said.

And though the so-called Latin explosion was a marketing ploy, to Mottola’s credit, it proved to be a successful one. Aguilera, Lopez and Shakira are now considered pop divas— the latter two even shared the stage during the 2020 Super Bowl halftime show.

As for Martin, he would eventually return to recording music in Spanish and has been a mainstay in Latin pop for decades. The Puerto Rican star just wrapped up a trilogy tour this year with Iglesias and Pitbull — most of the songs on Martin’s setlist were in Spanish — and can be seen on Apple TV’s drama “Palm Royale.”

In the 25 years since the release of “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” the U.S. Latino population has doubled — more than 63 million as of 2022, or approximately 19% of the U.S. population — which has fueled the exponential growth of the Latin music industry. The Recording Industry Assn. of America recently reported that revenue for the all-encompassing genre (which includes musica Mexicana and reggaeton) hit an all-time high of $1.4 billion in 2023, a 14% growth from its previous peak in 2005.

A new crop of artists has been able to reach the heights of Martin’s success without the need to attune its Latino identity to appease a white majority.

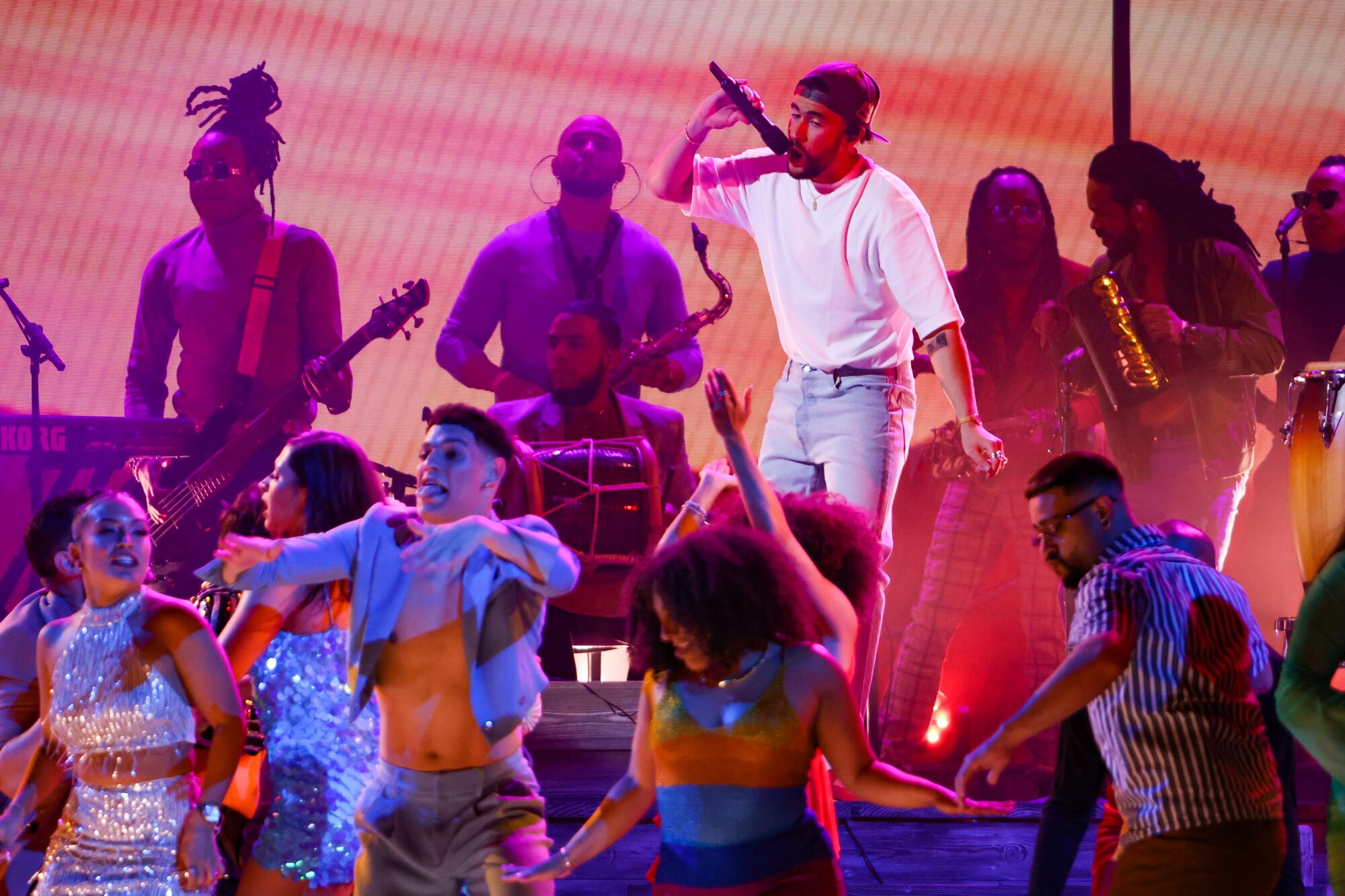

Mexico’s corrido tumbado star Peso Pluma was YouTube’s most streamed artist in 2023. Colombian singer Karol G was named Billboard’s woman of the year in 2024. Puerto Rican reggaeton trap star Bad Bunny recently co-chaired the Met Gala, a year after his performance at the 65th Grammys — a standout set that prompted backlash against CBS after the network used “singing in non-English” in lieu of transcribing his Spanish lyrics in the broadcast’s closed captioning. CBS President and Chief Executive George Cheeks apologized a week later for the snafu.

And yet, none of the top charting Latino stars has released an English album.

“[Latin Music] is American music too,” Valdes-Rodriguez said. “We’re not crossing over to anything.”