Lisa Boone is a features writer for the Los Angeles Times. Since 2003, she has covered home design, gardening, parenting, houseplants, even youth sports. She is a native of Los Angeles.

- Share via

1

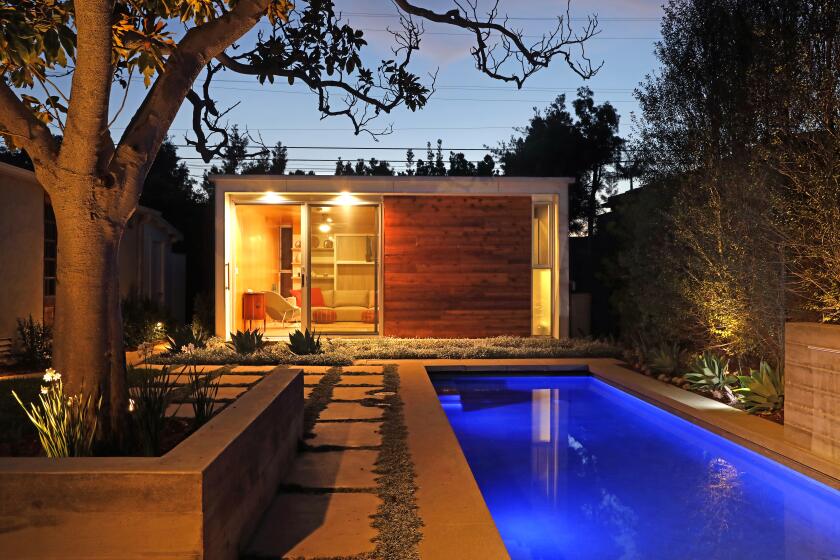

Rarely do detached garages evoke a sense of sleek sophistication. The exception? A garage-turned accessory dwelling unit, or ADU, in West L.A. that thoughtfully disguises the structure’s original purpose.

Inspired by a series of California laws that were designed to promote the development of accessory dwelling units, or “granny flats” (the laws were modified again last year in an attempt to address California’s housing needs), Justin Nasatir and Mara Grobins Nasatir purchased a 1,200-square-foot house in West Los Angeles in 2017 with the goal of transforming the detached, two-car garage into an income-generating property.

The black and white kitchen, a collaboration between designers Mary Casper and Tamar Barnoon, features custom-painted, face-framed cabinets.

(Kay Mashiach)

“When we saw the large garage and its proximity to the Expo Line, we thought it was a good candidate for an ADU,” Justin said. “We were thinking about it as a rental unit because it had its own entrance in the alley, didn’t have parking requirements and it was transit-adjacent. We thought it would be a good thing to improve housing supply as well as add to the value of our house and help us financially.”

This eco-friendly ADU is a simple solution to limited space: It’s just 320 square feet. The result? A WFH retreat that also houses guests when needed.

To help them make the garage livable, the Nasatirs tapped designers Mary Casper of Social Studies Projects and Tamar Barnoon. The goal, completed in 2021: Transform the garage into a bright, private rental property that feels like home.

From the beginning, the ordinary 600-square-foot stucco garage was a design challenge. “In terms of the layout, there weren’t a lot of options,” said Justin, who wanted a separate bedroom and a three-quarter bathroom so that the unit could accommodate more than one person.

A bifold door, framed in Douglas fir, opens to a courtyard patio.

(Kay Mashiach)

After living in the house for several years, the couple had developed a good sense of what they needed to do to make the alley-facing garage, which backs an automotive detail shop and rental-car facility, inhabitable.

“We wanted it to have light and be comfortable, but at the same time, we didn’t want people looking in the windows,” Mara said. “Because it’s on a commercial alley with large trucks driving through, we also didn’t want people to feel like the alley was right there.”

In an effort to address noise and privacy concerns, Casper relocated the entrance from the former garage-door position on the alley to a private courtyard patio. She then divided the interior into three living areas — a bedroom, a bathroom and an open kitchen and living room, creating a living area that connects to the courtyard through a new set of bi-fold doors. Although there are no windows on the east wall, the unit receives a surplus of southern light thanks to the folding door.

For further light, the designers added a series of clerestory windows that are arranged on a grid, with reeded glass for privacy. Paper Akari Noguchi pendant lamps in the living room and bedroom brighten those spaces and add drama. Skylights illuminate the bathroom and kitchen.

A dramatic blue-black exterior distinguishes the ADU from the main house.

(Kay Mashiach)

Influenced by the couple’s fondness for cabins, the designers installed Douglas fir-framed windows and doors throughout. “These bring textures of the outdoors — blue skies, green foliage — into the space without sacrificing privacy,” Casper said. They also painted the exterior of the ADU a dramatic blue-black tone to distinguish it from the main house.

In an innovative take on backyard “granny flats,” architects Melissa and Amanda Shin design an ADU that faces the street, while a two-story main house is installed in the back.

Polished concrete floors, which stand out against the home’s simple black and white palette in the kitchen and bathroom, were key to elevating the “garage” sensibility.

“We didn’t have the option of changing the footprint or roof height, but we added a new concrete floor because the original flooring was dirty and sloped,” Mara said. “We wanted the space to be sleek, stylish and contemporary.”

Reeded glass windows provide privacy and light.

(Kay Mashiach)

In a dramatic move, Casper and Barnoon installed custom cabinets painted black and white and topped them with a black eco-friendly, paper-based material by Richlite — usually used for countertops — that will naturally patina over time.

“Our choice of custom cabinets was able to make use of every inch of the limited space and manage alignments with clerestory windows in a way that prefabricated systems can’t,” Casper said. “Similarly, our choice to use mass-produced biscuit tile and black floor tiles blocked specially to use a different tile size on the shower floor, bath floor, shower wall and wainscotting affords the space greater detail than you’d typically see with those materials.”

With elderly parents and tenants in mind, the couple considered mobility issues when it came to some of their design choices. “When I chose the door handles, I chose a lever handle because my mom said it was hard to grasp the round knobs in our house,” Mara said. “We were concerned about tripping hazards and accessibility. We wanted to make sure that people can get in and move around easily.”

Transom windows above the doors of the ADU add light to the interiors.

(Kay Mashiach)

The architecture is both modest and grand, Mara said. And in the middle of the city, just three blocks from mass transit, the ADU feels like a luxurious getaway, “even though its location on the alley never changed,” Casper said.

And although the couple admit it was hard to lose the garage in terms of storage space (the couple have two parking spaces in front), they are happy with Casper’s compromise: A storage unit was added to the front wall of the ADU facing the yard and main house.

“I don’t think we could live without the storage,” Justin said. “It’s perfect for things like Christmas decorations, sports equipment and luggage.”

While single-family homes are typically required to provide two covered parking spaces and one space for ADUs, the Nasatirs were able to give up their garage because the new addition is within one-half mile walking distance of the Expo Line (now known as the E Line).

A skylight and a bifold door illuminate the main living area of the ADU.

(Kay Mashiach)

“Replacement covered parking for the main house is not required when covered parking is removed in conjunction with the construction of the ADU — both of which were the case with our project,” Casper explained. “We provided two uncovered spaces to replace the two covered spaces lost through the conversion, which is allowable.”

Over the past year, the couple, who have a 5-year-old and are both lawyers, said they feel lucky to be able to use the ADU to work from home during the coronavirus pandemic.

The alley-facing garage before it was transformed into an ADU.

(Tamar Barnoon)

“Right now, the ADU is being used as a workspace and guesthouse, but in the long term we hope to rent it out,” Justin said. “When we started, we had a vision for a one-bedroom house, which isn’t something you often see in Los Angeles. If I were single, or we were a younger couple, I think it would be a really great place to live. I’m surprised by how comfortable it is. There are not a lot of one-bedroom houses in L.A. like this. It has its own yard and entry point, and because of the new insulation [per California’s Title 24 energy requirements], it is relatively quiet.”

Mara, who didn’t want to overdo the simple structure, said: “We didn’t want to be pretentious and pretend it wasn’t a garage.”

Still, she added with a laugh, “It’s nicer than our main house.”

More stories about ADUs

They turned a one-car garage into a stunning ADU to house their parents. You can too

He challenged himself to build an ADU for under $100,000. What’s his secret?

She turned an unpermitted backyard studio into the ultimate WFH hideaway

She built a granny flat in Echo Park: How it saved her during the pandemic

How Los Angeles is bringing high design to the granny flat — while saving time and money

The L.A. ‘granny flat’ built for climate change: Take a look at the eco-chic inside

SoCal small-space living: 24 homes that inspire