Ryan Faughnder is a senior editor with the Los Angeles Times’ Company Town team, which covers the business of entertainment. He also hosts the entertainment industry newsletter The Wide Shot. A San Diego native, he earned a master’s degree in journalism from USC and a bachelor’s in English from UC Santa Barbara. Before joining The Times in 2013, he wrote for the Los Angeles Business Journal and Bloomberg News.

- Share via

1

Andrew Fried and his company Boardwalk Pictures are behind Netflix documentaries like “Cheer,” “Last Chance U” and Showtime’s “We Need to Talk About Cosby.”

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

In November 2018, comedian and television host W. Kamau Bell walked into the Santa Monica offices of Boardwalk Pictures, the production company known for “Chef’s Table” and “Last Chance U,” with an idea for a documentary about stand-up comedians.

Boardwalk President Andrew Fried had been pitched every “‘Chef’s Table’ of Fill in the Blank” imaginable since the show’s premiere in 2015. Auto mechanics. Surfers. You name it. But for Fried, a self-described failed comic, the idea of profiling funny people was appealing.

Eventually, the meeting among Bell, Fried and producer Jordan Wynn turned to the topic of famous comedy specials. Fried mentioned his favorite was 1983’s “Bill Cosby: Himself.” “What do I do with that now?” Fried asked.

Cosby, a Black cultural pioneer once lauded as “America’s dad,” had recently been convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to prison. (Cosby’s conviction was later thrown out by Pennsylvania’s highest court.) Reckoning with Cosby’s legacy could make for a powerful story, if done right.

W. Kamau Bell’s ‘We Need to Talk About Cosby’ is a compelling, complicated wrestling match with the legacy of the cultural icon and alleged rapist.

“I remember [Bell] stroking his beard, smiling and laughing, but also talking about the very, very real stuff,” Fried said of the meeting. “And then the next morning, I received a very, very long email from Kamau Bell, saying he couldn’t stop thinking about our conversation since he left our office.”

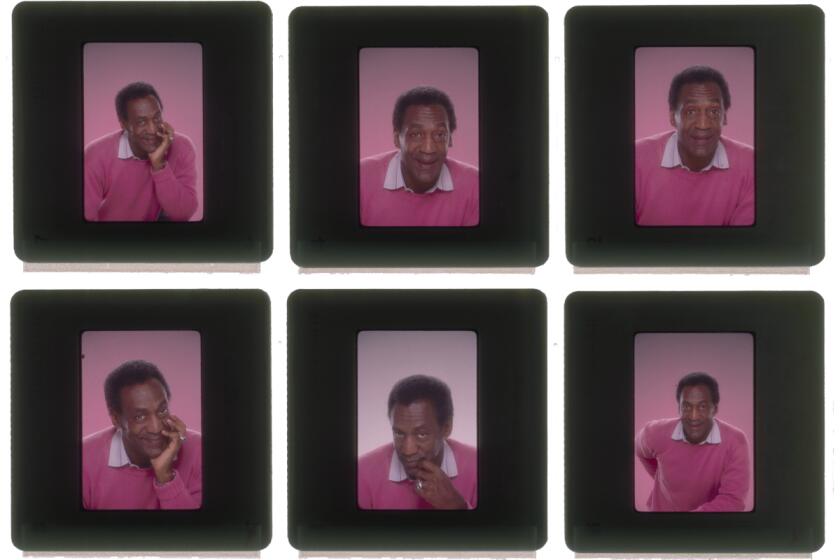

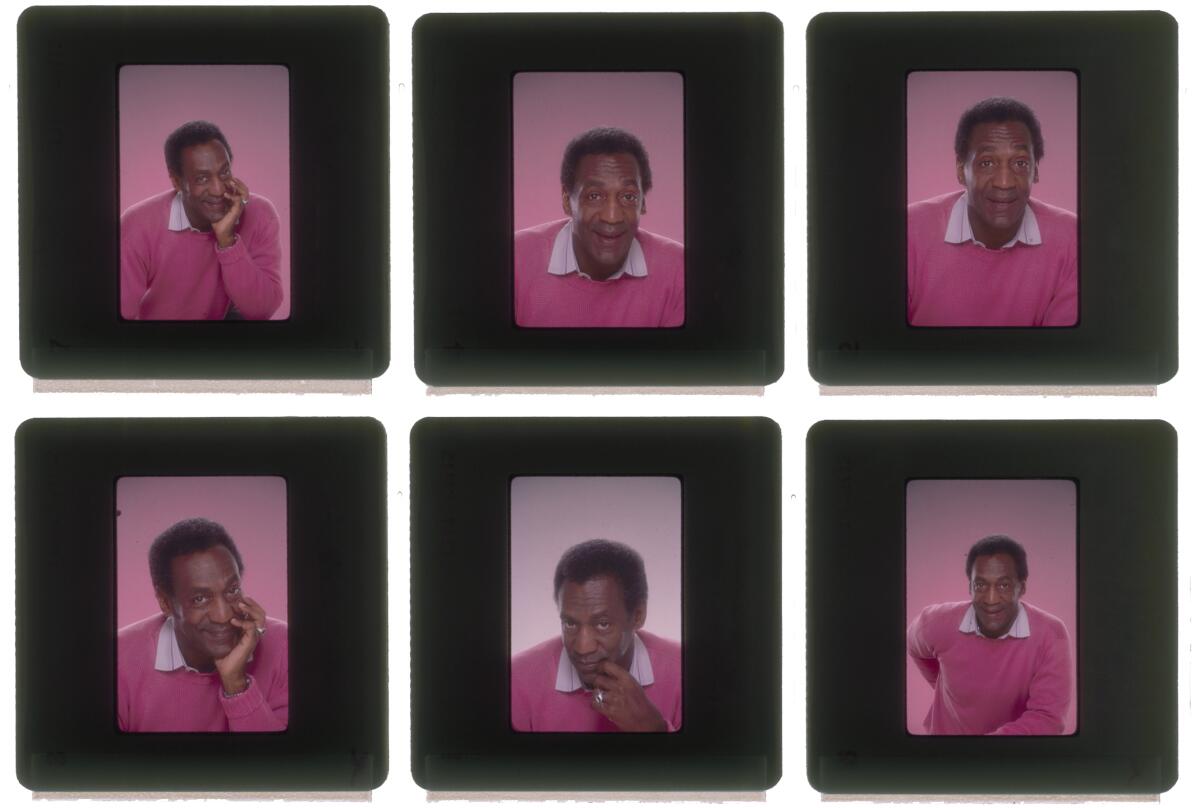

W. Kamau Bell’s docuseries “We Need to Talk About Cosby.”

(Mario Casilli / mptvimages / Showtime )

The project that evolved from those initial talks, the four-part series “We Need to Talk About Cosby,” debuted last month at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival and premiered Jan. 30 on Showtime. It’s one of the latest high-profile shows from Boardwalk Pictures, which has also made the critically acclaimed “Cheer.”

Since founding Boardwalk 12 years ago, Fried has been at the center of the transformation of documentaries from a genre with niche appeal to one of the fastest-growing draws for streaming and television audiences.

That appetite has grown rapidly in the last two years, according to research firm Parrot Analytics. From January 2020 to December 2021, U.S. demand for digital original documentaries grew 83%, while average interest in all other categories of original series increased 31%, according to Parrot data.

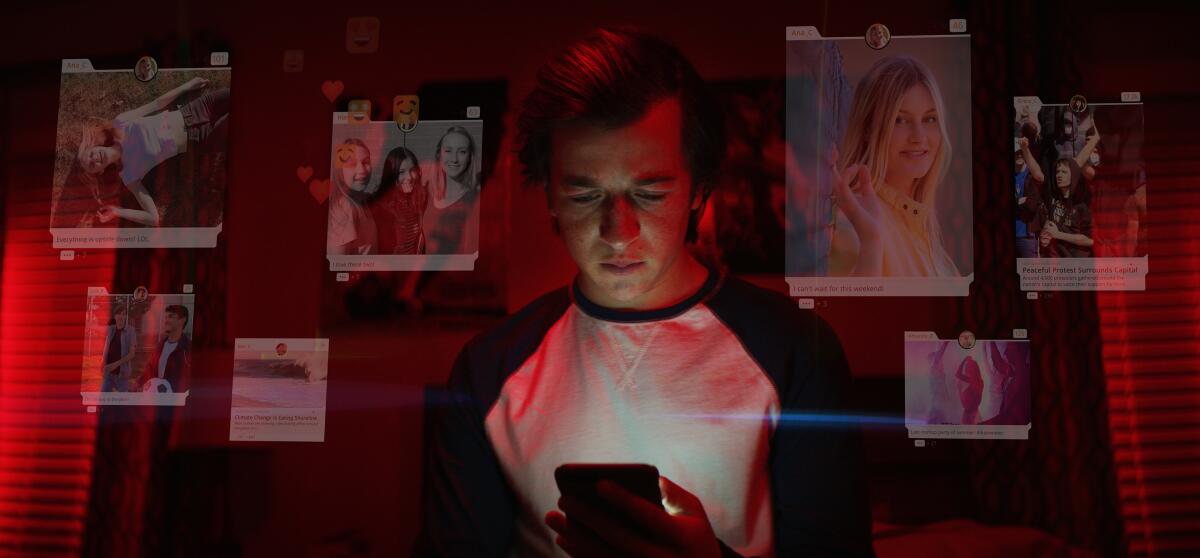

Streaming has made documentaries on obscure subjects easier for viewers to find and watch. Popular programs also appeal to viewers’ thirst for nostalgia (HBO Max’s “Beanie Mania”), as well as their interest in cults (HBO’s “The Vow”), internet culture (Netflix’s “The Social Dilemma”) and music (Lifetime’s “Janet Jackson”).

“What we’ve seen is that docs have shifted from being art-house fare to being discovered on these streaming platforms,” said Sarah Aubrey, head of original content for HBO Max. “It has left the niche territory and really exploded into just yet another form of storytelling for people, rather than being the purview of art-house cinemas and film festivals.”

HBO helped kick in the door with “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst,” which became an unlikely pop culture obsession in 2015. A true-crime explosion followed, with Netflix’s “Making a Murderer” and “Wild Wild Country,” and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic with “Tiger King.”

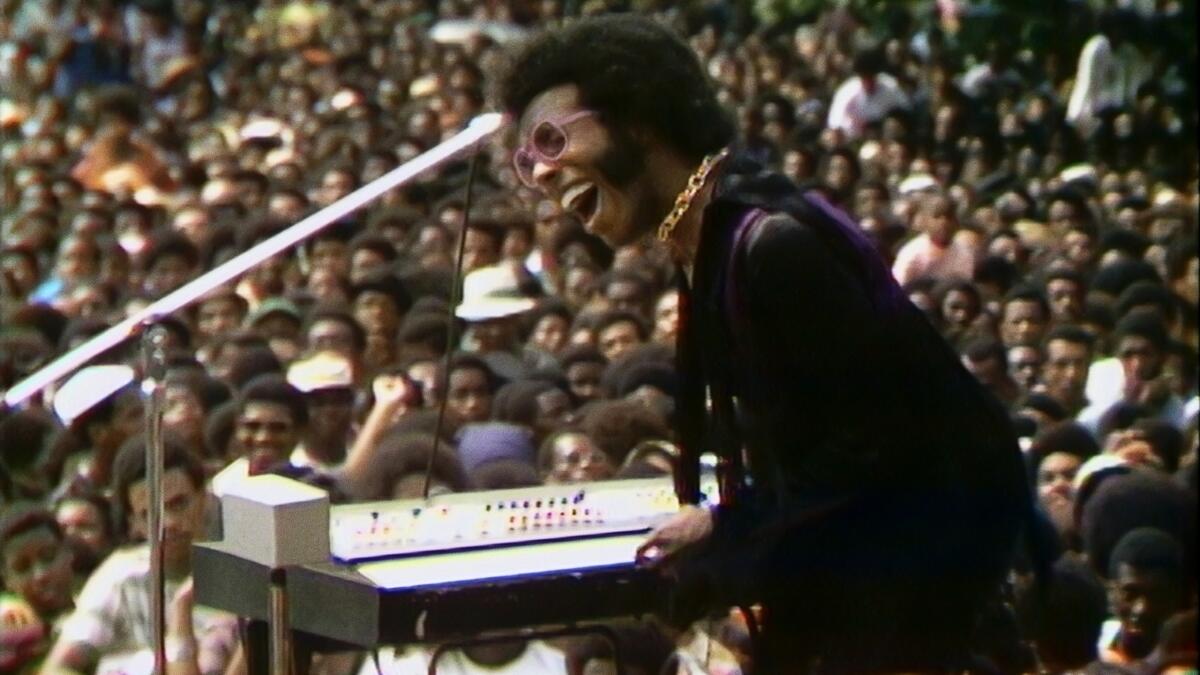

Film productions such as National Geographic’s “Free Solo” and Magnolia Pictures’ “RBG” haven’t just won awards; they’ve also been box office hits. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s “Summer of Soul” sold for $12 million at last year’s Sundance Film Festival to Walt Disney Co.’s Searchlight Pictures and Hulu.

(Jimmy Chin / National Geographic)

Sly Stone performing at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, featured in the documentary “Summer of Soul.”

(Searchlight Pictures)

As the audience has grown for documentary programming, so have budgets, largely thanks to companies like Netflix. Docs are no longer just about passion and modest budgets. Docuseries typically cost $750,000 to $1 million per episode to produce, industry insiders say.

“That genre is an integral part of Netflix and an integral part of the TV ecosystem in general, compared to maybe even 20 years ago,” said Brandon Riegg, vice president of nonfiction series and comedy specials at Netflix. “The proof is there in terms of the volume that we’ve had for those particular pieces of IP and those franchises.”

Boardwalk has capitalized on the demand. Its take on the food-competition format — “The Big Brunch,” hosted by “Schitt’s Creek’s” Dan Levy — will premiere on HBO Max later this year. “Race: Bubba Wallace,” a limited series about the only Black driver in the NASCAR Cup Series, hits Netflix this month.

Its films include last year’s “Val” (Amazon), made from footage that actor Val Kilmer shot himself over decades; and 2019’s “The Black Godfather” (Netflix), about influential music executive Clarence Avant.

Boardwalk’s staff has doubled to 40 people in two years. The company has gone from two to three shows in production simultaneously five years ago to about 20 projects in active development or production at a time today. Executives declined to disclose financial details, but they said revenue has roughly doubled every two years. For Netflix alone, Boardwalk has produced more than 25 series.

A Long Island native, Fried tried his hand at stand-up comedy at clubs in New York after he left Emory University in Atlanta. After two years at his grandfather’s real estate business, he embarked on his entertainment career.

While working at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2004, Fried was hired by Jon Kamen to join RadicalMedia, where he got his first producing role on the Jay-Z documentary “Fade to Black.” He cut his teeth on the Sundance Channel series “Iconoclasts” and on films like the 2008 Britney Spears documentary “Britney: For the Record,” which took him to Los Angeles.

At the time, nonfiction storytelling existed at two extremes in television. On one end was the 2000s explosion in reality TV shows such as “Jon & Kate Plus 8” and competition series such as “American Idol.” On the other were arty and educational documentaries. There wasn’t much in the middle, where Fried saw an opportunity.

“I remember, when we would talk about shows, we would say, ‘Is this for commercial success, or do you want to get nominated for awards?’” Fried said. “And I think what we started to say, in the early days of Boardwalk, is, ‘Both.’ You can do things that are meaningful and elevated. You don’t have to choose.”

(Exposure Labs / Netflix)

(Netflix / Everett Collection)

In 2015, its show “Chef’s Table,” created by “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” director David Gelb, became Netflix’s first original documentary series.

Its success was a key moment for the company and the visual style of docuseries. They tried to make “Planet Earth” for food. Shots were carefully planned out, with closeups of culinary masters plating intricate dishes set to classical music.

Boardwalk was careful not to flood the market with similar shows, said Lee White, a WME agent who has worked with Fried for years.

“It was a very deliberate thing that we didn’t go out with a bunch of projects that were the ‘“Chef’s Table” of X,’ because A, you cannibalize this show, and B, you pigeonhole yourself,” White said.

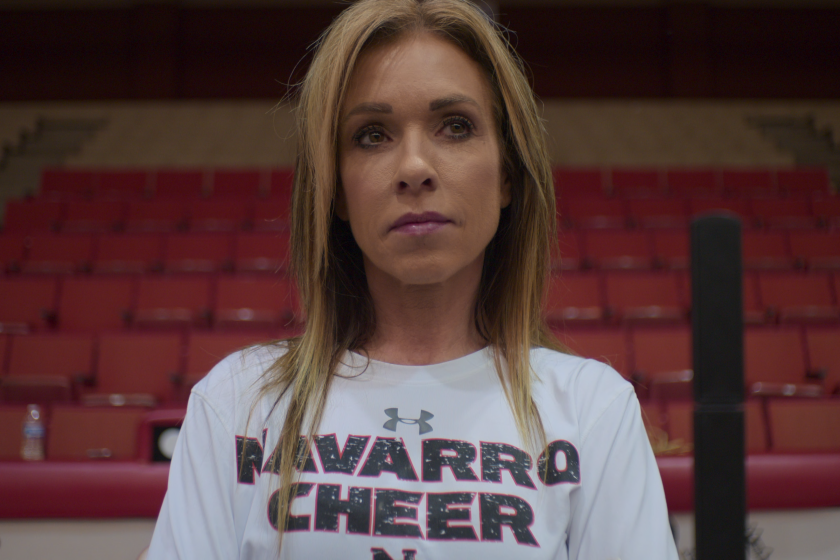

Boardwalk’s 2020 show “Cheer,” created by “Last Chance U” director Greg Whiteley, showed how documentaries could break into the mainstream, turning its young Navarro College athletes and their hard-driving coach, Monica Aldama, into national celebrities. The series was spoofed by “Saturday Night Live,” and the cast appeared on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show.”

Jeron Hazelwood of Trinity Valley Community College Cheer in Season 2 of “Cheer.”

(Netflix)

But with that popularity came a dark side.

Newfound fame, a pandemic and disturbing allegations against a teammate sideswiped the stars of ‘Cheer.’ And filmmakers captured it all on camera.

In September, the FBI arrested fan-favorite cheerleader Jerry Harris — who had interviewed Brad Pitt on the Oscars red carpet and delivered one of his effusive “mat talks” with Oprah Winfrey — on a child pornography charge. Harris was later indicted on charges of sexual abuse of minors. He pleaded not guilty in December.

“Jerry was supposed to be presenting at the Emmys that week,” Fried said. “But instead, he was in a jail cell. There was a very real human component of, ‘What do we do now?’”

The filmmakers tried to tackle the subject directly. In the fifth episode of Season 2 of “Cheer,” which debuted last month, Whiteley features interviews with the twin brothers who allege that Harris solicited them for sex and explicit photos; their mother; and their lawyer, Sarah Klein, who criticizes Aldama’s handling of the allegations.

“We Need to Talk About Cosby” also presented unique challenges as real-world events changed the story during filming.

Bell and his crew were on what was supposed to be one of their last days of filming in Philadelphia when he started getting text messages and news alerts that Cosby had been released from prison. In a scene that appears in the documentary, the cameras turn to a shocked Bell. The crew held a Zoom meeting after the ruling to process their emotions.

Bell credited Boardwalk executives for supporting him through the unexpected twists. Bell had parlayed his career as a political stand-up into a role hosting CNN’s “United Shades of America” and was influenced by the likes of Michael Moore’s “Bowling for Columbine” and PBS’ “Eyes on the Prize.” But he’d never taken on a project like this.

“If there was ever a time where I could understand going, ‘All right, man, shut it down, we’re done here,’ this was it,” Bell said. “They were just like, ‘Let’s take a breath. We don’t have to make a decision right now. We will figure this out.’”

Looking at growth opportunities, Boardwalk has started developing scripted shows in tandem with its documentaries, similar to what other companies do when adapting podcasts and docs into shows and movies. It’s also looking to self-finance more projects.

While companies like Reese Witherspoon’s Hello Sunshine are selling at sky-high valuations right now, Fried — Boardwalk’s sole owner — said he is not interested in merging with a larger studio.

“We’ve won a few awards now, but it feels to me, truthfully, like we’re just getting to the good part,” Fried said. “We’ve never had a huge infusion of capital to just explode the thing. We’ve just grown through the work.”