Under Netflix’s harsh spotlight, a ‘devastated’ cheerleading squad tries to regroup

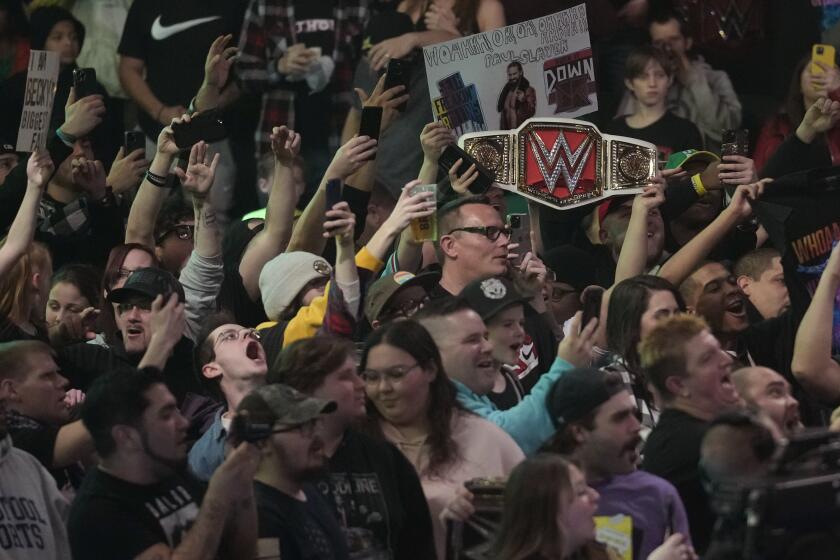

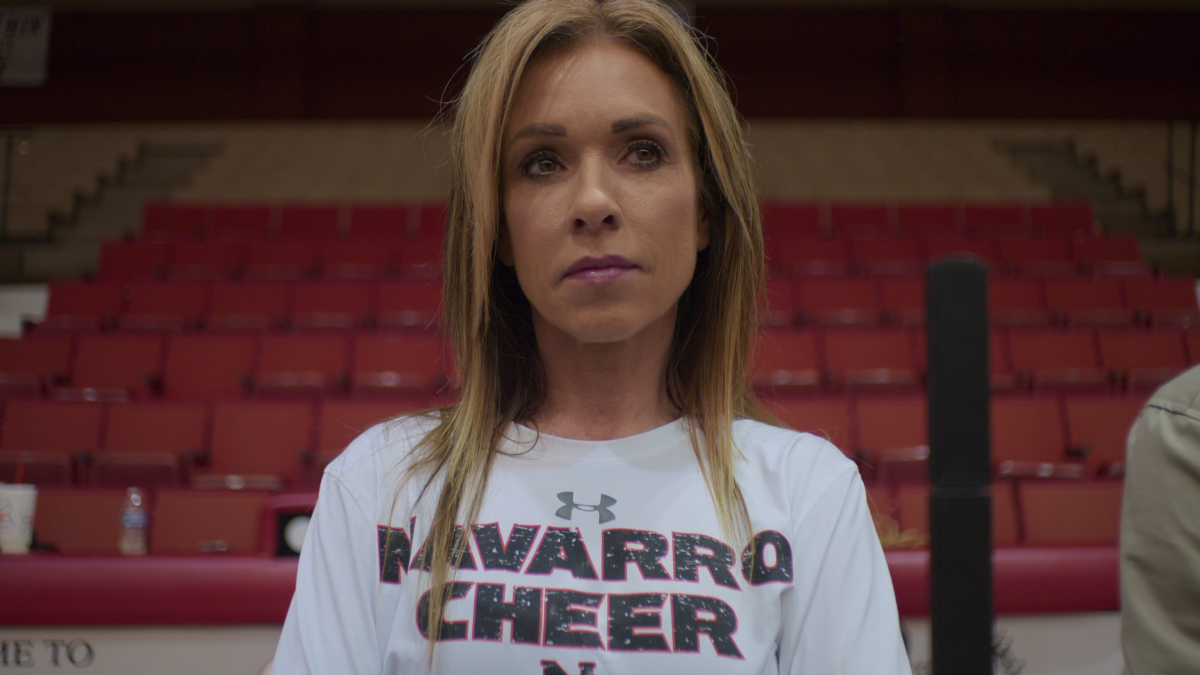

When “Cheer” was released in January 2020, the Netflix docuseries about elite cheerleaders at a Texas community college became an instant cultural sensation. Within weeks, it turned tough-as-nails coach Monica Aldama and her gritty athletes into overnight celebrities who got spoofed on “Saturday Night Live,” appeared on “Ellen” and interviewed Brad Pitt on the Oscars red carpet.

As inspiring as it was unflinching, “Cheer” resonated well beyond the cheerleading community because it told a story about young people overcoming unthinkable adversity — including poverty, sexual abuse and parental neglect — to compete in a physically and emotionally punishing sport often dismissed as a sideline spectacle.

But the hardships of Season 1 are nothing compared to Season 2. In the nine episodes that premiered Wednesday on Netflix, the series documents a turbulent two years interrupted by a deadly pandemic, upended by disturbing allegations against a beloved teammate and tainted by the pressures of newfound fame.

“There are some pretty complicated issues that we raised in Season 1,” says director Greg Whiteley, “but not quite like what we had to tackle in Season 2.”

The Navarro College athletes and their rivals at Trinity Valley Community College, who are newly featured in Season 2, were weeks away from vying for the National Cheerleaders Assn. championship in Daytona Beach, Fla., when the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the world in March 2020. Daytona was canceled, leaving the athletes without a competition, and “Cheer” without a finale or a clear narrative path forward.

Then, things got worse.

In September 2020, Jerry Harris, the ebullient underdog whose giddy mat talk, heartbreaking backstory and infectious passion for cheerleading made him Season 1’s breakout star, was arrested and charged with production of child pornography for allegedly soliciting and receiving explicit material from a minor over social media. In December he was indicted on additional child pornography charges. (He has denied the allegations.)

Whiteley and his crew returned to Texas in early 2021 — nearly a full year after COVID hit — to follow the cheerleaders as they regrouped after a lost season and grappled with the allegations against Harris.

Netflix docuseries ‘Cheer’ has turned the Navarro College cheerleaders and their no-nonsense coach into reality stars.

“Cheer” addresses the charges head on, examining the case and its impact on Harris’ teammates in a gut-wrenching episode called “Jerry.” Whiteley interviews Sam and Charlie (their last names are not disclosed), the twin brothers who allege that Harris solicited them for sex and explicit photos; their mother; and their lawyer, Sarah Klein, who criticizes Aldama for what she sees as an insufficient statement in response to the allegations. (“I have no sympathy for her,” Klein says.)

Whiteley says he never considered not moving forward with the series in light of the allegations against Harris. Nor did he feel that he had somehow misrepresented his subject in Season 1.

“Human beings are complicated people. As a filmmaking team, we’re as good as anyone at creating a portrait and filming somebody authentically. But in the three months that we’re allowed to film someone, we’re not going to get to the bottom of someone,” he says. “I think as long as we’re humble about that, and that when we do learn something new, we have the integrity to also cover it, not ignore it, then I can sleep at night knowing I’m doing my job.”

The news breaks during an already difficult time for the Navarro athletes, many of whom are struggling with the isolation of COVID-19 or floundering without the leadership of Aldama, who is away competing on “Dancing With the Stars.” Harris’ friends struggle to square the allegations with the person they know — and reach varying conclusions. “I don’t care how famous you are,” La’Darius Marshall, a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, says in the episode. “That don’t give you the right to do stuff like this, especially when you know one of your best friends went through something like that.” A tearful Gabi Butler concludes, “I can’t turn my back on him because he was there for me when I needed it.”

“This was an event that was so impactful on the lives of the team. Even if Jerry was no longer physically present while we were filming, his presence still was very large,” Whiteley says. “You could feel a team that was completely devastated. It was as though a close friend they thought they knew had died. And that isn’t something that goes away in a week, or a month, or even a year.”

Season 2 finds Aldama and her team dealing with the roller-coaster ride of celebrity. They marvel at the opportunities they’ve received because of the show — like trying avocado toast for the first time — and use downtime between practice to record lucrative Cameo messages. But the spotlight also creates tension, particularly when Aldama agrees to go on “Dancing With the Stars” and appoints a replacement coach, the improbably named Kailee Peppers, during a vulnerable time.

Aldama, the stoic heroine of Season 1, emerges as a more fallible figure this time around, bristling at the criticism she gets on social media and having a painful falling out with one of her star athletes. “There is a certain emotional vulnerability that she shared with us under some very, very difficult circumstances. I left that interaction admiring her more than I did in Season 1,” Whiteley says.

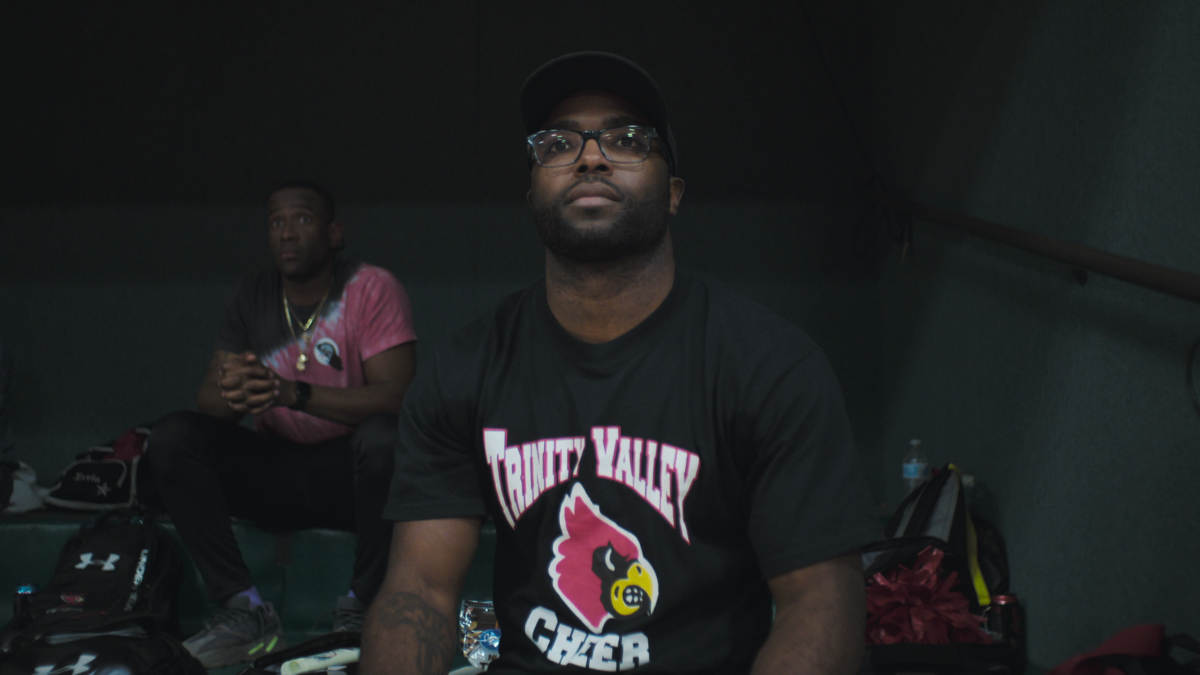

Whiteley also introduces us to a new cast of compelling characters, including Navarro’s arch-rivals at Trinity Valley Community College, who finished in second place in 2019 and are hungry for a comeback.

The team is led by coach Vontae Johnson, a soft-spoken former football player who was eager to be a part of “Cheer.” “We liked how it portrayed the athletes and athleticism. There’s no way that we would turn it down this season,” he says.

Johnson encourages his cheerleaders to go out of their comfort zone and put on a showier performance in order to close the gap with the Navarro squad, which is known for its high-energy style.

“You’ve got the best cheerleading programs in the history of cheerleading separated by 30 miles. It didn’t take a genius to go, ‘We should spend more time with this other school,’” Whiteley says.

The decision to follow TVCC may have been a no-brainer, but it also made it even more excruciating for the filmmaker to document the teams when they finally faced off in Daytona Beach last April. Whiteley recalls the disorienting experience of being with the losing team as they wept over the results, then following the winners as they took a joyful ceremonial plunge into the ocean. He knew that “if we could somehow get an audience to feel even a semblance of what I’m feeling right now,” they’d have a special season, he says.

“There aren’t good guys in this and bad guys in this. There are two teams, and we want the audience to love them both.”