Huntington Library acquires the papers of Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Pynchon, the famously reclusive postmodern novelist known for intricate, cacophonous “Great American” novels, has decided on the institution that will house his papers and make his life known to the world — and it’s in Southern California.

The Huntington Library has acquired the archives of Pynchon, 85 — a collection of typescripts and drafts of each of his novels, handwritten notes, correspondence with publishers and research — which were prepared by his son, Jackson Pynchon, the museum announced on Wednesday.

In all, 48 boxes packed with Pynchon’s writings will be archived and available to scholars at the library in San Marino by the end of 2023.

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

“This is a landmark collection for us, because he is a writer of great stature and literary importance,” said Karen Lawrence, president of the Huntington and herself a literary scholar focused on James Joyce. Pynchon, whose kaleidoscopic “Gravity’s Rainbow” is often compared to Joyce’s “Ulysses,” was a major influence on generations of authors, including Salman Rushdie, David Foster Wallace and Dave Eggers.

“The archive will generate enormous interest in the scholarly community, and we’re thrilled that this living writer has selected the Huntington,” Lawrence added.

Pynchon’s son, Jackson, was deeply involved in the acquisition and organization of his father’s papers.

“When The Huntington approached us, we were excited by their aerospace and mathematics archives, and particularly attracted to their extraordinary map collection,” Jackson Pynchon said in a statement released by the Huntington. “When we learned of the scale and rigor of their independent scholarly programs, which provide exceptional resources for academic research in the humanities, we were confident that the Pynchon archive had found its home.”

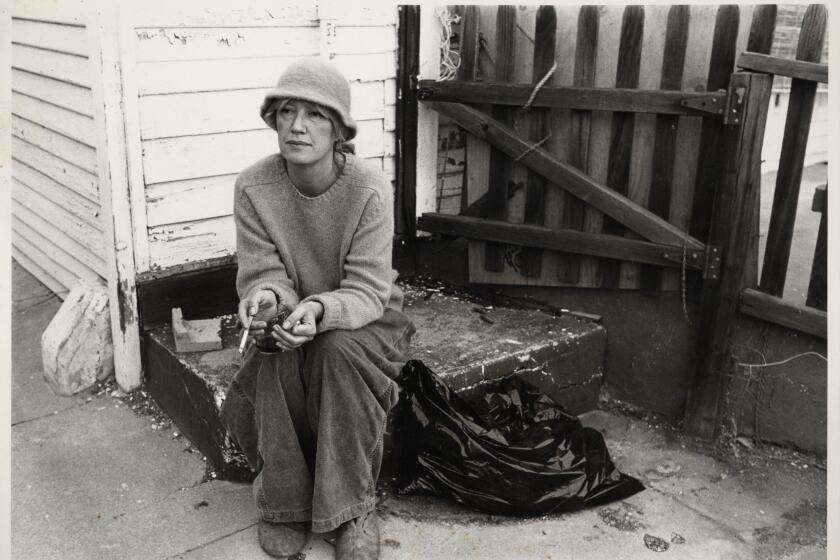

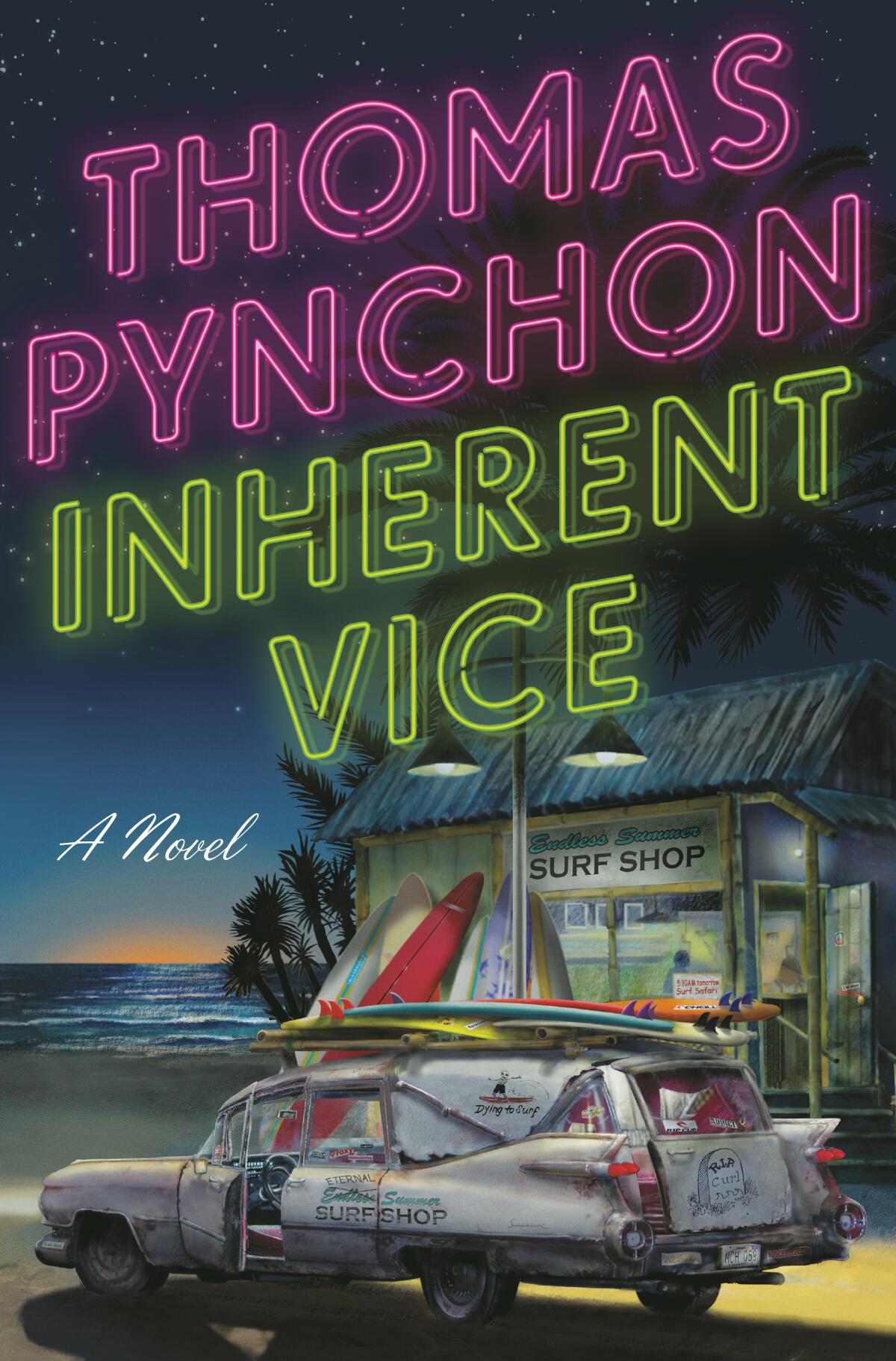

It is a homecoming of sorts. Following a stint in the U.S. Navy and after graduating from Cornell University, Pynchon found immediate literary success. His first novel, “V,” published in 1963, won a William Faulkner award for best first novel. He wrote much of “Gravity’s Rainbow,” his third and most celebrated novel, while living in a duplex in Manhattan Beach — which became the setting of his 2009 novel “Inherent Vice.”

Let’s make this a whole lot easier.

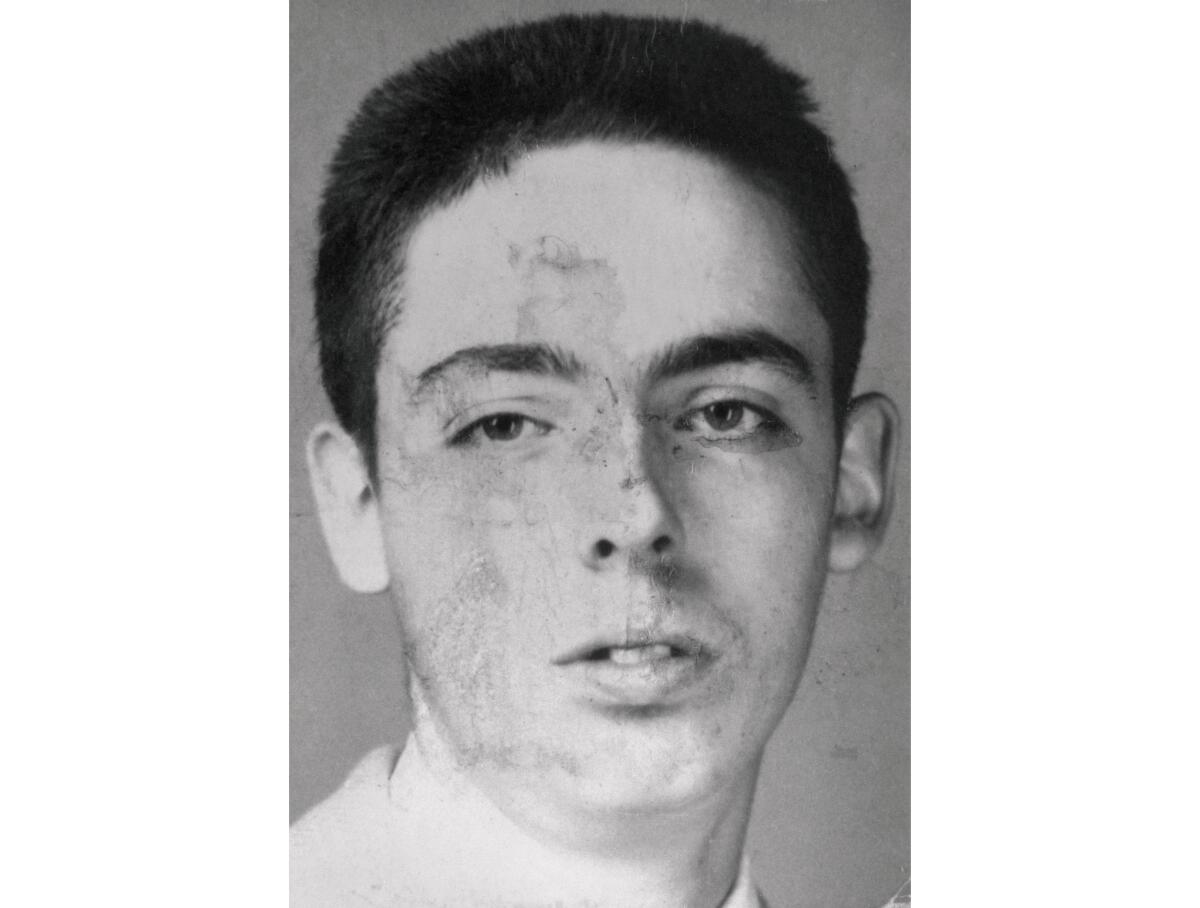

Yet throughout his life and career, Pynchon has preferred privacy, shying from the fame his novels brought him. He has sent others in his place to receive his literary awards; he avoids photographs and dodges reporters. Pynchon scholars and biographers have had to piece together tidbits of his life. The Huntington’s acquisition will surely transform their work.

When a CNN reporter tracked him down for a 1997 story, Pynchon said over the phone, “My belief is that ‘recluse’ is a code word generated by journalists, meaning, ‘Doesn’t like to talk to reporters.’”

Lawrence said both Thomas and Jackson Pynchon were in close communication throughout the acquisition process. Pynchon’s wife, Melanie Jackson, is a prominent literary agent who counts him among her clients. (The family declined to comment beyond Jackson Pynchon’s statement.)

“We found them very good to deal with,” Lawrence said, adding that Jackson Pynchon had already put a lot of legwork into organizing his father’s writings. And those writings, she believes, say more about him than his public persona or lack thereof: “He has been a very private person who’s concentrated on his writing and getting the writing done, and an enormous prodigious amount of reading clearly is behind his work.”

For the record:

11:10 a.m. Dec. 15, 2022An earlier version of this article referenced the 1969 Watts Rebellion. The uprising took place in 1965. Also, Stephen M. Tomaske was a librarian at Cal State L.A., not UCLA, and the Huntington is home to his collection of Pynchoniana, not his papers.

While living in Manhattan Beach, Pynchon wrote an account of the 1965 Watts Rebellion for the New York Times Magazine. And much like the characters of his books, he wandered throughout the U.S., including stints in Seattle, New Mexico, Houston and Northern California (as channeled into his loopy novel about pot growers, “Vineland”) before settling in his native New York.

His work, however, will be making the opposite journey.

What drew Pynchon to the Huntington was, in part, the impressive range of its collections, Lawrence said. In addition to rare works by Shakespeare, Chaucer and Joyce as well as a Gutenberg Bible, the library also houses the collections of authors including Octavia E. Butler, Eve Babitz, Christopher Isherwood, Paul Theroux and Hilary Mantel.

Southern California’s 1960s past reemerges from the haze in this Chandler-like tale, set in the age of cannabis.

The Huntington is also home to a collection of Pynchoniana from Stephen M. Tomaske, a Cal State L.A. librarian whose side gig was collecting as much work by and about Pynchon as possible, from yearbook clippings to recorded interviews with Pynchon’s Navy shipmates.

And then there were the collections cited by Jackson Pynchon, focused on topics that recur throughout his father’s work.

“There are many echoes of things which are in the background of Pynchon’s writing,” said Sandra Brooke, director of the library. Aerospace engineering and mathematics were key to “Gravity’s Rainbow,” whose title describes the parabolic arc of the V2 rocket — “A screaming comes across the sky,” as the book famously opens. The Huntington’s array of early American maps includes those marking the Mason-Dixon line, the geographical star of his 1997 historical novel, “Mason & Dixon.” The museum also centers the culture of California — setting and subject of “Vineland,” “Inherent Vice” and “The Crying of Lot 49.”

Yet Pynchon’s writings don’t merely fit in with the Huntington’s existing collections, Brooke said; they put them in a new context, pulling them into Pynchon’s solar system.

“It just kind of reshapes how so many things in our collections will be viewed and seen,” Brooke said.

Karla Nielsen, curator of literary collections at the Huntington, was the first from the museum to contact the Pynchons about acquiring the archive. Over the ensuing conversations they were not only willing to share the work of this private man publicly; they were eager to do it.

The Huntington Library has acquired letters, photos, drafts, artwork and more by L.A. writers Eve Babitz, Eloise Klein Healy and Gloria Stuart.

One selling point was the Huntington’s scholars-in-residence programs, Nielsen said, which invite international researchers to spend months in the archives. This felt true to a writer who, as his papers make clear, underwent a “very intensive research process” before he ever sat down to write.

Researching Pynchon, whose work teems with period-specific vocabularies, expansive worlds, scientific and historical rabbit holes and buried allusions, is no small feat of its own. As Pynchon himself once said, he’d like to “keep scholars busy for several generations.”