The archive is the art at this Hammer Biennial ‘Made in L.A.’ exhibit

The Chinatown art space Human Resources was in the throes of a deep cleaning. But the space hadn’t been a mess. The cleaning was part of a durational performance piece, held over three days, put on by three women artists. It was 2013 and, as visitors popped into the gallery during business hours, artists Hailey Loman, Lucy Lord Campana and Gaea Woods vigorously scrubbed the floors and washed the walls. One day they even cleaned the ceiling. The piece, titled “Cleaning Human Resources,” explored the boundaries between what is for show and what is hidden as well as what is an artifact, what is ephemera and what is residue.

Loman was frustrated, at the time, with the video documentation of the performance, finding it limiting — it didn’t push boundaries or exist multidimensionally afterward and instead seemed to say, simply: “This is something you missed.” She and Human Resources co-founder Eric Kim began thinking more about the nature of archiving performance work in general, with an eye to how to give it life after the work was done, how to share and grow it. They archived props from “Cleaning Human Resources,” such as dirty rags and half-empty 409 bottles, as well as images of the piece in progress.

“The video footage or photograph stills, if shown in a white cube gallery or elsewhere [later], would be a new artwork,” Loman says. “We needed to create a room where we had certain signifiers and clues [indicating], ‘This is a place for in-process works to be looked at and explored and celebrated. These are things for research — I’m not positing that this is finished. And what happens next?’”

What happened next was Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA), a nonprofit, public archive and library of contemporary art-making primarily from artists and institutions in the Los Angeles area. LACA will participate in the Hammer Museum’s biennial, “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living,” which opens Oct. 1.

Loman and Kim co-founded the archive in 2013, though he is no longer involved; Loman serves as director. LACA is free and open to anyone wishing to visit or contribute materials — artist donors needn’t have shown with or have any previous relationship with LACA. The archive now has more than 20,000 objects from about 6,000 artists and others: props and costumes from performances, letters, studio leases, pay stubs, rental receipts, police reports, handwritten process notes and class syllabi.

Many of LACA’s holdings are from Chinatown-based entities. The first archive acquired was from Human Resources, and it included grant rejection letters, overdue bills and performance programs. The second archive was from the artist-run community radio station KCHUNG Radio, which contributed all of its audio recordings.

Individual artists, such as Spanish-born, L.A.-based Patricia Fernández and L.A.-based multimedia artist Scott Benzel, donated their entire archives. Workers from the Museum of Contemporary Art donated materials from the museum’s 2019 unionizing activities, including text messages, meeting minutes, pins and pamphlets. The former Main Museum in downtown L.A. donated its archive, which includes construction photographs and architectural renderings as well as materials from its “Office Hours” consultations with artists.

By collecting and framing contemporary art and ephemera — and making those materials accessible to artists studying other artists’ techniques, as well as students, journalists, scholars and others — LACA is lifting the veil on the art-making process, illuminating the complexities and granular decisions that go into creating an individual work. It’s also offering insight into the everyday lives of artists and institutions, including unique and universal struggles.

“And we’re showing that art is in the everyday,” Loman says. “That can lead, down the road, to imagining something better. Things aren’t how we want them to be — there are unhoused folks that we casually walk past. If we have a regular artistic questioning practice, we can start to notice things, which leads to demanding change.”

For “Made in L.A.,” LACA will present an immersive installation, in an employee break room setting, with selections from its holdings on view. That includes ephemera from the recent workers’ rights strike by dancers at Star Garden, a topless dive bar in North Hollywood, and rave maps by L. Coats, part of her project “desiredfx,” a free rave series at tucked-away locations around L.A. that’s still in existence.

The idea behind the installation is not only to show visitors what’s in the archive but also to question traditionally held ideas around rest, particularly for artists.

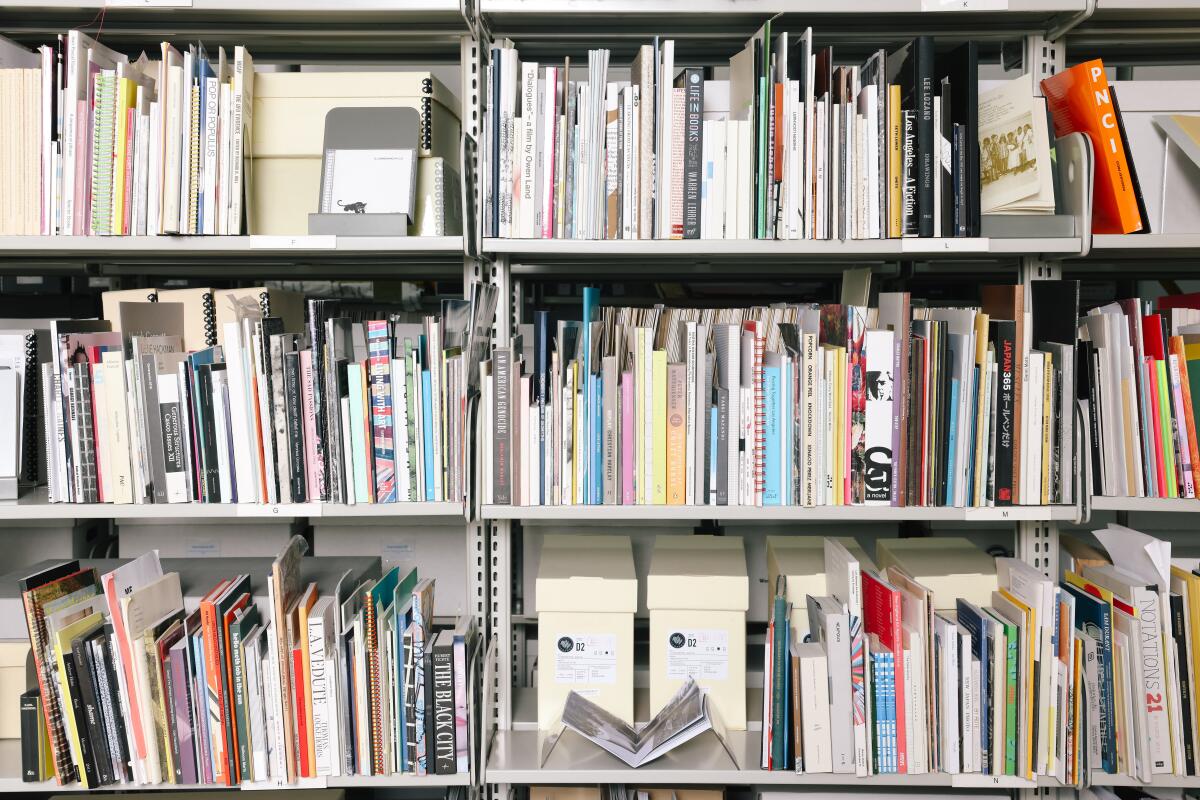

On a recent visit to LACA, in a Chinatown office suite, the space is sparse and counterintuitively bright, with steel shelving housing artists’ materials in acid-free boxes and flat files. One area holds irregular-sized materials, such as large limited-edition artist kits or a super-tiny, 1-inch-tall and 2-inch-wide handmade artist book. There’s a shelf for brochures and another for music sheets and an artist book library. Some of the archiving materials themselves have been documented: special acid-free folders, hand-me-downs from Getty Museum staffers, show their provenance on exterior labels.

LACA is very much a group effort, Loman explains. She’s the only paid employee, as of this year, and she’s somewhat sheepish about her director title, as decisions often are made collaboratively among about half a dozen artist-archivists, most part-time volunteers with some workers paid a stipend or receiving payment through fellowships.

Artists have played a key role in the evolution of LACA since day one. When it was being founded, Loman and Kim surveyed art-world communities, asking, “What’s missing for you in the arts?”

“We asked: What’s happening?” Loman says. “Are you really paying your bills? Are you OK? What would this feel like for you if we started collecting these materials? What’s needed?”

Now artists who donate materials “directly impact the collection,” Loman says. They write metadata into the database, framing their materials. They consult on the storage and presentation. “We work closely with them. It’s one of the benefits of being a living archive — the artists are alive still and collections are growing and changing.”

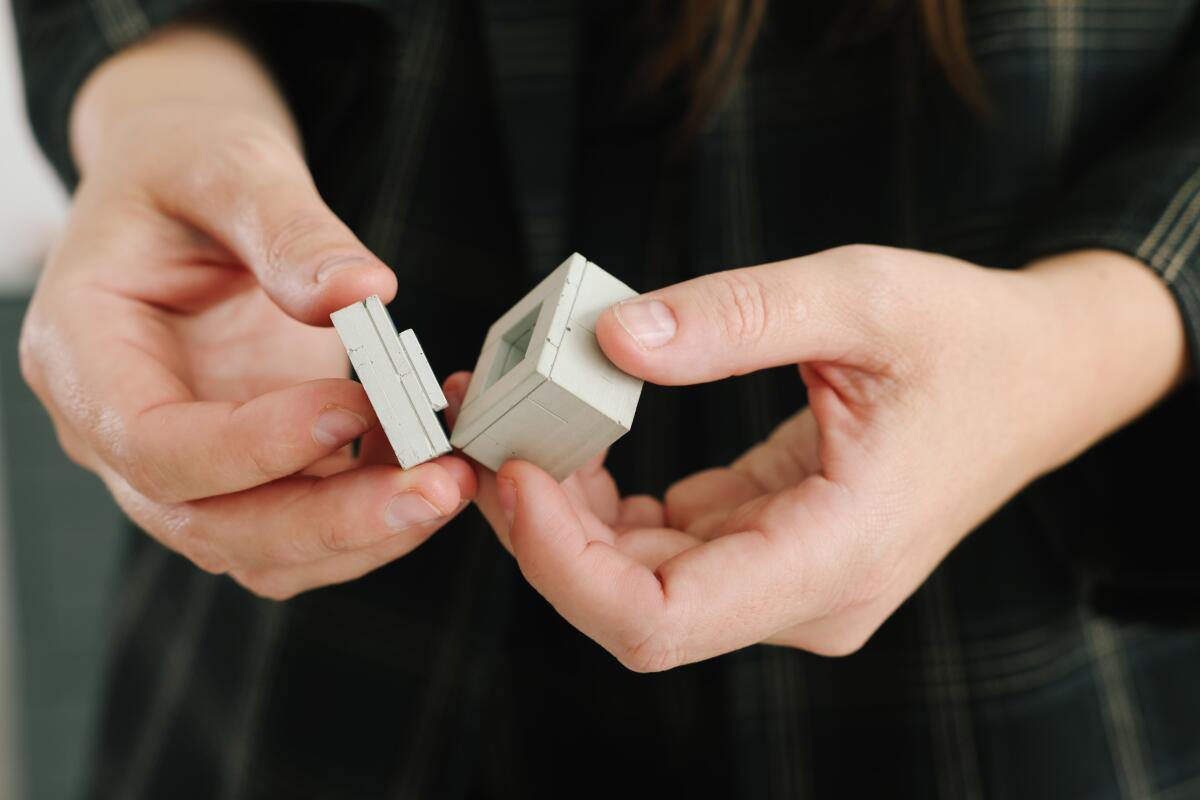

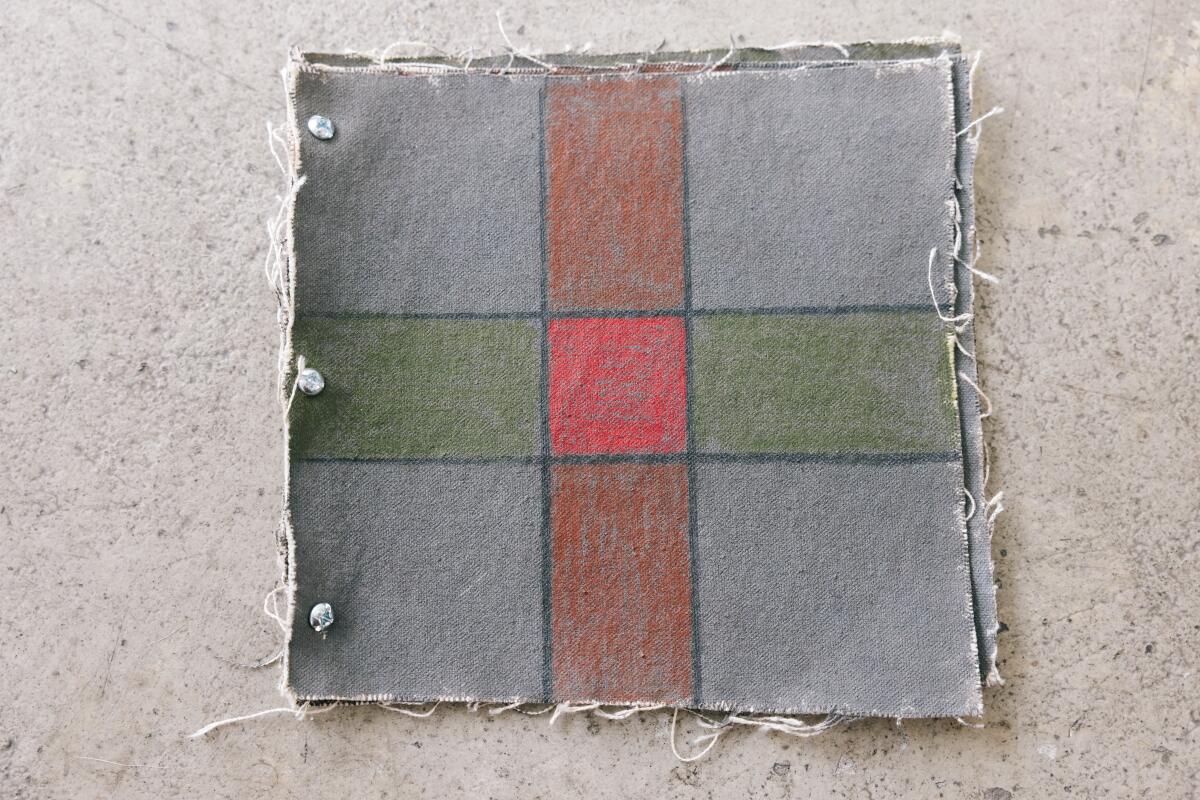

During our visit, objects from the archive were laid out on a small conference room table. That included selections from Fernández’s archive: hand-painted tiles, fabric swatches testing dyes and oil paints for a work, exhibition schedules and a handwritten breastfeeding schedule the artist wrote while developing work for an upcoming show. “Almost nothing is finished,” Loman says. “It’s all stuff around the process of art-making.”

Also on the table: a smattering of items centered around dance, joy and rave spaces. There’s a giant, hand-painted canvas that once served as the dance floor for Tantrum Cabarave, a former queer dance party that’s also donating to LACA food menus from its party nights, DJ set lists and photographs.

In 2016 the experimental music and art venue Pehrspace donated its archive to LACA in a medicine cabinet, removed from a bathroom wall, filled with random objects: an empty whiskey bottle, a paper party hat, a fire extinguisher, party decorations and what appears to be a crumpled, handwritten IOU note for “$70.” LACA consulted with a museum conservator, who said the best approach, for preservation, would be to remove the objects and bag everything separately.

“We thought: Well, it’s more information that it’s all crammed together — that the keys sit with the party hat — than it be properly archived and fumigated and bagged,” Loman says. “It tells a story.”

That approach is counterintuitive. Most art archives are housed in light- and temperature-controlled storage rooms to protect materials. But LACA’s “bare minimum” approach is important to its identity, which, in part, is about challenging established ideas about how archives operate. Materials at LACA are stored in acid-free containers, consultations are conducted away from windows and LACA is cognizant of temperature. But the experience of interacting with the objects — creating a more relaxed space for visitors that’s conducive to learning while the materials do still exist — is a priority over preserving them forever. In fact, the concept of anything lasting forever is “preposterous,” Loman says.

“I get ‘Why would I donate my objects here if the Getty can have this exist forever?’” Loman says. “And I say, ‘What is exist forever for you?’ Because who knows what forever really means. We’re in global warming. Also things get lost to floods and fires and whiteness.”

Artists donating materials are made well aware of this thinking in advance.

Accessibility is also a top concern. Some museum archives are accessible only to visitors who have already paid admission; others have difficult-to-navigate websites or are located in settings that require a car or multiple buses to get to; some are open only to individuals affiliated with other institutions. Removing these barriers to entry is a priority for LACA. As is permissibility.

“Lots of archives, you show up and are told to leave immediately and go wash your hands and put your bag in a locker,” Loman says. “It’s meaningful to us that we’re welcoming over hand-washing. I trust that you will be careful rather than being punitive. Would you rather your materials get looked at and used by 100 people or by two people wearing gloves?!”

The Hammer Museum installation — in a converted storage room — aims to be especially inviting. Like many break rooms, it will feature a coffee pot, with hot coffee for visitors, and microwave leftovers as well as a seating area for guests.

Works will be divided into three groupings — “Work,” “Break” and “Pleasure” — presented in classic glass vitrines as well as in boxes on shelves that visitors can open and look through. Books will be on view and small TV screens will display video documentation from performances.

“We’re going to remix, reshuffle, the archival collections,” Loman says. “We’re looking at how, in the workplace, our rest, our breaks are often not for us. They’re to work better, faster, harder.”

The “Work” section will feature archived materials around sex work and caregiving related to death and sickness as well as child care. The “Break” section will display materials around spirituality, rituals and mental health. “Artworks that speak to, ‘We’re refusing the conditions that we didn’t even choose, that we live under,’” Loman says.

The “Pleasure” section will feature cookout material, dance material and ways that we congregate, as well as work around the erotic.

Employee break rooms are generally dismal spaces, fluorescent-lit, frozen pizza-scented rooms oozing a sense of lack.

“By the time you show up, your 10-minute break is already over, so you’re stealing more time on the clock,” Loman says. “We steal the best doughnuts in the morning, maybe a mug, and then it’s dismal and haphazard. But also, we’re together and there are still moments of joy that we can carve out.”

The Hammer installation, she adds, is a metaphor for the modern artist’s life in America.

“The majority of us artists are not OK — paying bills, survival, making art — we have to take multiple jobs. So I hope this installation is an imagining space toward building something better for the future.”