- Share via

- An L.A. Times investigation found that many dogs sold as California-bred come from mass breeders in the Midwest.

- Unsuspecting pet buyers can face heartache and thousands of dollars in vet bills when their puppies get sick or die.

- California is destroying veterinary records that provide details about a pet’s origin and health status.

Blaring music drowned out the barking, but there was no masking the neglect inside the sweltering Riverside County garage.

Jamie Abruzzo, a Missouri middle school teacher who picked up a summer job trucking puppies around the country, was overcome by anger as he took in the filth and feces that surrounded him.

Outside, the temperature neared triple digits. Inside, where the air conditioner wasn’t working, dozens of puppies and kittens were jammed into small cages and storage bins lined with soiled shredded paper. Water containers nearby were empty.

Abruzzo cradled his delivery, a 10-week-old Boston terrier that had made its way from an Indiana breeder to a broker, then to a crate inside his transport van. After two days on the road, this was the puppy’s next stop — the detached garage turned holding pen in an Inland Empire suburb.

The driver knew where this multi-state pipeline was supposed to lead for the animals left unattended that day: loving homes. But what Abruzzo stumbled into was the underbelly of California’s lucrative, unregulated puppy market.

And it haunted him.

A Times investigation found that truckloads of doodles, French bulldogs and other expensive dogs from profit-driven mass breeders pour into the state from the Midwest, feeding an underground market where they are resold by people claiming to be small, local home breeders.

The trail of imported dogs — some from operators cited by state and federal officials for neglect — persists, despite California’s efforts to stem the flow, The Times found.

Did your dog come from the puppy pipeline?

To see if your pet was listed in travel documents unearthed by The Times, enter its 15-digit microchip number into this database.

California passed a law in 2017 barring pet stores from selling dogs, hoping that would cut off bulk shipments from puppy mills into the state, and it later strengthened the ban to make it difficult to pass commercially bred dogs off as rescues. Gov. Gavin Newsom touted the laws as putting an end to the state’s role in the “cruel puppy mill industry for good.”

But the laws had a major unintended consequence — driving the puppy trade further underground.

Generally, it’s not illegal for an individual to import dogs and resell them. All dogs brought in to the state to be sold require a certificate issued by a federally accredited veterinarian listing the animal’s origin, intended destination and verification they are healthy to travel. But for puppies resold in California, consumers are often left in the dark about where their pet really came from.

And California is turning a blind eye to a black market by destroying the veterinary records provided to the state that contain key details about the puppy resale trade, The Times found.

Under state law, the records should be sent to county health departments. But that’s not how it’s working in California’s disorganized system, The Times found. Many counties seemed unfamiliar with the records and unaware they’re supposed to receive them. Instead, other states from which dogs are exported routinely send the certificates to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

The CDFA acknowledges that it receives the travel certificates — and then immediately deletes the records since it has no authority over them. Some states told The Times they stopped sending the records to the CDFA, at its request.

With no clear way to trace their pet’s origin, buyers are often fooled into thinking they’re supporting reputable, local breeders, but are instead fueling a trade in which some puppies are born and raised in horrific conditions. Pet owners have been left heartbroken or facing thousands of dollars in veterinary bills when their new puppies get sick or die. Meanwhile, shelters across the state are overflowing.

To understand the scope of the puppy trade, The Times requested travel documents — called certificates of veterinary inspection — from all 50 states and received responses accounting for nearly 88,000 dogs.

The paper then analyzed the movement of more than 71,000 of them into California since 2019, when the pet retail ban went into effect. These travel certificates show how a network of resellers — including ex-cons and schemers — replaced pet stores as middlemen. Dogs brought from out of state are often rebranded as California-bred, fetching hundreds to thousands of dollars each.

The Times identified dozens of people — some using fake names and addresses — each of whom is listed as having imported more than 80 dogs into the state in the years after the retail ban. Some were listed on travel certificates as the destination for more than 500 puppies.

An overwhelming number of the dogs coming into California — more than 70% — were from Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma and Iowa, according to a Times analysis of travel certificates.

Many dogs were supplied by breeders cited or charged with abuse and neglect, including one in Wisconsin who knowingly transported puppies that had been diagnosed with the deadly and highly contagious parvovirus and failed to get them veterinary care. Another in Iowa for months hid dogs from authorities in a horse barn during inspections. Inspectors eventually were allowed in, and found two dead puppies and a severely emaciated golden retriever among other suffering dogs, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture records and a federal criminal complaint.

Federal inspectors examine dogs’ living conditions.

Hundreds more came to California from the compound of Steve Kruse, an Iowa breeder who once threw a bag of dead puppies at a federal inspector while being cited for animal welfare violations, according to USDA records reviewed by The Times. Kruse later told a USDA investigator that he did so because he blamed inspectors for stressing a dog that was nursing the pups to the point that she accidentally killed them.

Photos and videos of Kruse’s dogs with bleeding open wounds, decaying teeth and crusty infected eyes are documented in federal inspection reports. They show oozing sores between the toes of dogs who live on grated flooring. In one case, inspectors found handwritten notes instructing staff to pour various hot sauces into a husky’s wound to prevent licking. In a 2021 case, Kruse’s veterinarian deemed 199 of his dogs “incurable” before euthanizing them all in a single day, according to a note scribbled by the vet that was in USDA records reviewed by The Times. Kruse declined to comment, and the vet has since died. The USDA did not respond to questions about whether Kruse disputed its findings.

Nearly all of the puppies coming into California from Kruse’s compound had one thing in common — The Times found no record of the people and companies listed as their destination. But phone numbers and dog microchip numbers on those records, as well as court documents and interviews with buyers, led The Times to a prolific California importer, Monique Matthews.

The Norco garage where Abruzzo delivered the Boston terrier in 2021 belonged to Matthews, according to property and court records. She repeatedly declined to comment to The Times. Her attorney told The Times that she wasn’t living at the Norco address at the time, and that the animals there — most of which he said were healthy — were not hers. He refused to say who owned the animals.

Inside the garage that summer day, untended animals swarmed Abruzzo. They seemed hungry and thirsty. He found some containers, filled them with water from a spigot outside and vowed to never again deliver dogs to California.

When he returned to Missouri, he reported the neglect to Norco authorities and shared photos of the conditions inside. As it turned out, they knew the location well.

Karen Cochran was immediately smitten by the tiny white Westie with dark eyes and pointy ears that she purchased from a woman in a Norco CVS parking lot in 2018. She named the puppy Lemon and fastened a bright yellow collar around her neck.

The Westie named Lemon died 11 days after going home with her new owner.

At home, Cochran soon noticed something was off. Lemon was coughing and had bloody diarrhea. A vet prescribed antibiotics while waiting on test results.

A week later, Lemon was still sick and refused to eat. She was quiet and lethargic. Tests came back positive for parasites and the flu. Lemon also developed pneumonia. The puppy took quick shallow breaths as Cochran cradled her in her arms.

After 11 days in her new home, the puppy died.

Outraged and heartbroken, Cochran — through an online search — identified the woman who had used a fake name when she sold Lemon. Along with her photo were a slew of urgent warnings about the woman she learned was Matthews.

Cochran reported her puppy’s death to authorities.

Shortly after, officers found more than 50 puppies in stacks of cages and containers in Matthews’ Norco garage. The temperature in the building was 95 degrees and smelled of urine, according to a Norco Animal Services report reviewed by The Times. The ceiling fan and mounted air conditioning unit were off.

An officer noticed two lethargic black poodles having trouble breathing, the report said. One couldn’t keep itself up and didn’t move when an officer squeezed drops of water into its mouth.

Dehydrated, the poodle died overnight in the hospital.

Matthews was cited for violations including lacking a proper business license and failing to give dogs adequate room to stand or lie down in cages. She was fined $725. Cochran sued Matthews in small-claims court and won $2,855. But she says Matthews never paid.

Matthews’ attorney Dana Cole did not respond to questions about the case. He said The Times’ reporting was “full of inaccuracies,” but refused to identify any specific errors.

“Nothing happened to her, nothing,” Cochran said. “How is that possible?”

Frank Scagnamiglio, former head of Norco Animal Services who investigated Matthews before retiring in 2019, questioned where she sourced dogs and whether she actually bred them herself because there were always so many puppies on her property, but few adult dogs.

“If there’s no mom or dad, you need to question where the dogs came from,” he said. “Might be a puppy mill.”

Several years before Lemon died, complaints from buyers with sick dogs led investigators with the L.A. County district attorney’s office to serve a search warrant at Matthews’ Norco home. They found two “very ill” dogs in the garage, though the rest “appeared healthy, albeit thirsty,” according to an internal report reviewed by The Times. They declined to file charges due to insufficient evidence that she knew the dogs were sick at the time of sale.

The D.A.’s office could not prove Matthews was sourcing dogs from puppy mills.

“Circumstantially, of course, we could infer that that was exactly what Matthews was doing,” the D.A. report said.

In America, puppies are a big business. And it’s easy to see why.

An estimated 62 million American households have dogs, and one study found the pet industry drove $300 billion into the global economy last year. More than half of U.S. dog owners say they consider their pets as much a part of the family as their human relatives, according to the Pew Research Center.

Nationally, the U.S. Department of Agriculture licenses some 2,550 breeders, brokers and transporters authorized to have dogs. There are no federally licensed dog breeders in California.

A USDA license is required for anyone with five or more breeding dogs who sells to pet stores or online without meeting the customer in person. In annual visits, USDA inspectors enforce the Animal Welfare Act, which sets a low bar for care. For example, dogs housed in groups can legally spend their entire lives in a cage and females can breed over and over, with no limit.

“If there’s no mom or dad, you need to question where the dogs came from. Might be a puppy mill.”

— Frank Scagnamiglio, former head of Norco Animal Services

The agency allows consumers to view breeder inspection reports on a public database, but it can be difficult to navigate. In one case, inspection reports for Missouri breeder Philip M. Hoover, who sells to California buyers, turn up inconsistently depending on how you search his name. Hoover, who had 525 breeding dogs and puppies during his most recent inspection, declined a visit from Times reporters and refused to answer questions about travel records showing some of his dogs were among those going to California addresses that don’t exist.

The USDA also allows breeders to change their name or list a P.O. box instead of a kennel address. In Indiana, 16 breeders are licensed using the same two suites at a shopping center in Indianapolis.

In addition to USDA licensing requirements, 31 states have their own laws regulating commercial breeders, according to a 2023 report by the Animal Legal & Historical Center at the Michigan State University College of Law. They vary widely but generally require a breeder to be licensed and inspected.

In California, breeders or resellers are required to obtain permits and pay taxes on the sales of dogs. Selling more than two dogs without a permit is tax evasion and a misdemeanor crime, according to the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

The agency said it could not provide a list of California dog sellers with permits because of taxpayer privacy laws. The Times could not determine whether Matthews has one. When asked by email, her attorney did not respond.

California does not have a statewide licensing program for breeders operating here, instead relying on local jurisdictions for oversight. Some cities and counties require breeders to be licensed and inspected, but little information is made available online to help consumers vet them. The city of L.A. temporarily stopped issuing breeding licenses recently because of overcrowding at its shelters.

Many dog breeders in California are small hobby breeders or unlicensed backyard breeders. Large-scale breeders are primarily concentrated in the Midwest, where the puppy industry took off in the 1970s and ’80s. That’s when agriculture officials encouraged small poultry and hog farmers unable to compete with large farming corporations to raise dogs, said Bob Baker, executive director of the Missouri Alliance for Animal Legislation, which advocates for laws to protect animals from abuse and neglect. It was not a hard sell — dogs take up little space and often have a higher price tag.

Puppy mills proliferated after that. Their numbers are hard to gauge, as there is no all-embracing definition of what constitutes one. One federal judge defined puppy mills in a civil case in 1984 as breeding operations that put profits over animal welfare. Some advocacy groups consider all commercial breeding operations puppy mills, but also criticize smaller irresponsible backyard breeders. Puppy mills are not illegal, but many consumers would balk at buying from such facilities.

Mass breeders and brokers often market themselves with idealistic portraits of large free-roam farms and home-raised puppies, or refer to sales as adoptions to mirror the language of rescue groups, said John Goodwin, senior director of the Stop Puppy Mills campaign at the Humane Society of the United States.

Also, many puppies pass through at least one broker on their way into a family’s home, a process that obscures where their dog was born.

“We oftentimes get calls about ghost breeders who ... have burner phones,” said Jace Huggins, chief of humane law enforcement for the San Diego Humane Society.

Huggins said his office hears from people who have purchased sick dogs. “They want us to track down the person, and most of the time we can’t find them,” he said.

A surge in demand for puppies during the pandemic led to more dogs coming into California than before the pet store ban, but those numbers have since dropped, according to The Times’ analysis of 20 states that provided at least six years of records. In those states, veterinarians approved more than 16,000 dogs to be sent to California in 2020, while roughly 9,600 were approved last year. The remaining states provided records for only some years, or none at all. Not every travel certificate reflects a sale — some record people visiting California with their pets or moving into the state.

Most of the states in The Times’ analysis now send far fewer dogs to California compared with 2018 — the year before the pet retail ban went into effect. However, Ohio exports have nearly tripled since then, from nearly 1,500 dogs to more than 4,000 last year. The number of breeders and brokers has ballooned there in recent years, which animal advocates attributed to Ohio’s lax oversight. State inspectors, for example, give two days’ notice before site visits. Lawmakers in the state introduced legislation this year to end the practice.

The website for Bay Area Corgis in San Francisco says its policy forbids shipping puppies to buyers because “it’s detrimental to the puppy’s health.” But its founder, Kobe Tran, is listed on travel certificates for more than 130 puppies coming into California in the last two years, almost exclusively from Ohio. In an interview, Tran said unequivocally that he’s a breeder, not a broker, before conceding that he and his family buy 80% of their puppies from out of state to resell. Tran then hung up on reporters when asked if his customers know many of his dogs are actually from the Midwest.

Trina Kenney, along with her husband and children, was permanently banned last year from selling dogs over what a Los Angeles County judge called a “heinous” scheme to sell sick puppies. The Kenneys were ordered to pay more than $177,000 to several people whose dogs became ill or died, as well as nearly $1.2 million in attorneys fees. Yet, the Kenneys’ last name and address are listed on travel certificates signed by a veterinarian and reviewed by The Times as the destination for at least 29 puppies from Michigan in the weeks before and following the ban.

“You’re not gonna take away my right to sell anything,” Kenney had said in a deposition before the judge’s ruling. Kenney’s attorney told The Times that the family has been complying with the order and questioned the authenticity of the travel certificates because the name listed does not exactly match.

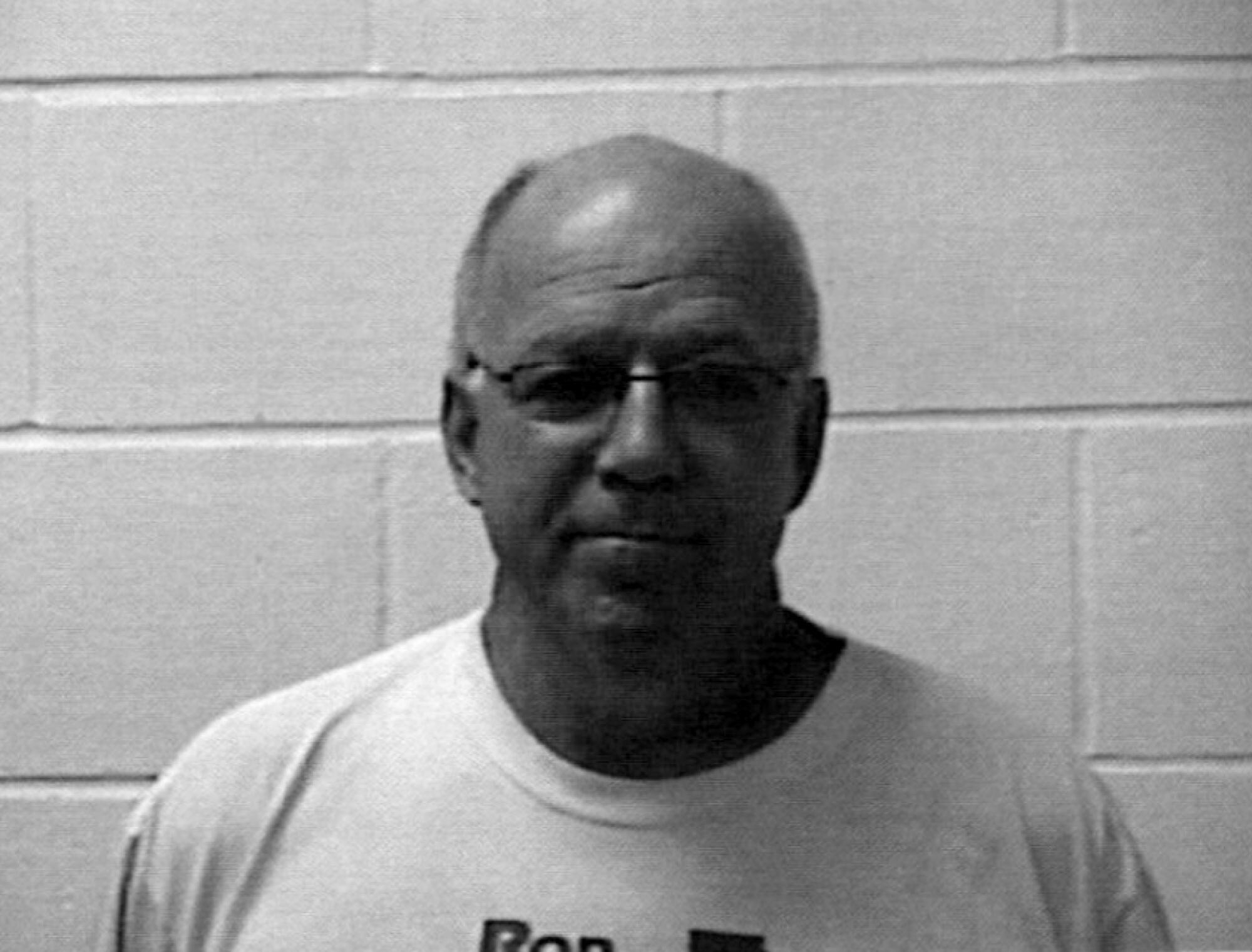

Trina Kenney during a 2021 video deposition.

The Times could not verify where the dogs ended up.

Some puppy resellers advertise matchmaking services that pair families with the right pet.

For the record:

12:05 a.m. Oct. 6, 2024This article has been updated to add comment from a representative of Doodles Los Angeles, claiming that it does veterinarian checks on dogs that it imports to make sure they are healthy.

Doodles Los Angeles, for example, had a steady flow of furry-faced puppies available online. Miriam Alperson and Daniel Zaraya of Doodles Los Angeles ordered roughly 500 puppies from Ohio since 2021, according to travel certificates. An attorney for the company declined to answer questions about whether customers are given breeder information, but said the company has a local, state-licensed veterinarian do health checks on dogs it imports. The attorney also said that it has temporarily suspended operations after receiving a “notice of violation” in Ventura County for not having a kennel license, which the company did not know was required.

Travis Sneed, a Silicon Valley groomer, said he breeds, trains and sells dogs to the public as well as to law enforcement agencies for therapy programs. He has prior convictions for defrauding a property owner and scamming people buying tech products online. Sneed operates Silicon Valley Goldendoodles at a sprawling estate he rents in Los Gatos, where his website touts “a strong emphasis on natural rearing.”

“Our Breeding Program exists to raise puppies to be trained as Service Dogs to assist the disabled,” the website says.

Travel certificates, obtained from the state of Wisconsin, show veterinarians approved more than 180 dogs to be shipped to Sneed’s operation from mass breeders since 2021. Roughly 40%, according to the documents, were from the kennel of Amos Allgyer, who was cited by state and federal inspectors for failing to treat dogs with parvo and ear conditions, among other violations. In an interview in May, Sneed said that he once co-owned two breeding dogs there but that he no longer works with Allgyer because the care provided to the dogs didn’t meet his standards.

“We look at it from a quality-of-life perspective for the dog, and then we also look at it from a liability perspective,” Sneed said. “Our relationship with Amos was maybe only, like, 10 months or a year.”

In a recent interview, he said he had never worked with Allgyer and had mistaken him for a different person with the same last name, but refused to provide more information. Sneed then said he did not order or receive any of the puppies from the handful of breeders listed on travel records provided by Wisconsin’s Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. Allgyer could not be reached for comment.

Veterinarian Raymond Leonard attested on the forms that Allgyer’s puppies were going to Silicon Valley Goldendoodes.

“Anything on the certificate it is my responsibility that it’s correct,” he said. “The destination is not supposed to be anywhere other than that destination.”

Sneed told reporters he sells anywhere from 80 to 350 dogs a year, with four breeding dogs at his Los Gatos facility and 29 at so-called guardian homes where the dogs live with a family as a pet. He said about a dozen of those are out of state. After The Times began reporting on Sneed, he said he received a threatening phone call complaining about reporters’ inquiries.

An attorney for Sneed said his client “assures me that he has never imported out-of-state dogs for resale.”

For Matthews, puppies have long been a family business.

As a teenager, she worked at her dad’s Pets Delight store in Covina that sold dogs and supplies, according to three people who know her. Her mom had a store by the same name in South Pasadena; her stepdad had one in Monrovia. Eventually, she opened her own pet shop in Glendora, state business registration records show. Matthews was convicted of misdemeanor animal neglect at her store about two decades ago, according to the L.A. district attorney’s report.

Her attorney said that “the allegations involved technical sanitary violations at the family pet store that were quickly remedied.” Cole added that he visited the store and found it “exceptionally clean.”

All the Pets Delight stores eventually closed and Matthews at some point started selling dogs online. Ads linked to her phone numbers were written to appeal to consumers concerned with ethical breeding practices. “Raised in our home just like family,” said one for a Shiba Inu.

An ex-boyfriend once told a Riverside County sheriff’s sergeant that during the Christmas season, Matthews made $100,000 a month selling puppies, according to a 2018 search warrant affidavit and an interview with the sergeant. The ex added that she forged paperwork to claim puppies were purebred and registered with the American Kennel Club, allowing her to hike up the price, the affidavit said. Matthews’ attorney did not respond to the forgery claim.

Matthews’ customers told The Times she was charming and knew what to say to put them at ease. Some said she claimed she was in veterinary school or worked as a veterinary technician.

In one meeting, a couple told The Times, Matthews fawned over an 8-week-old Boston terrier. “If you guys don’t take her, we’re keeping her,” Matthews told Nicole and Andrew Taylor, closing the sale for $1,400. Another buyer vying for a shih tzu was probed about whether her young children were kind to animals, suggesting a robust vetting process. The puppy sold for $1,100.

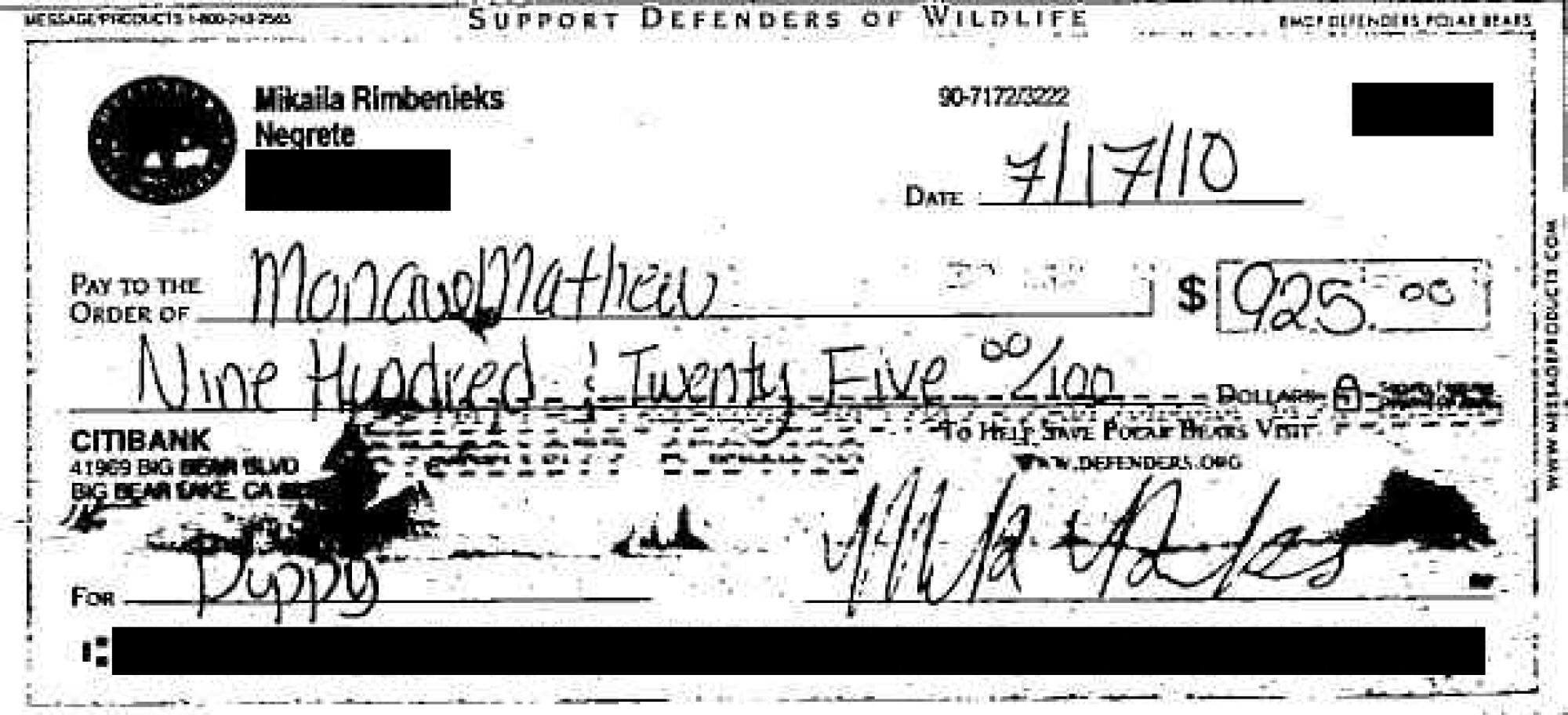

Over the years, she used various aliases — Anna, Jessica, Vickie — in her dealings, according to civil lawsuits, a district attorney report, animal control records and interviews with buyers. One buyer said Matthews had her make a $925 check out to “Mona Mathew,” and later discovered someone had scribbled over her handwriting changing the name to “Monque.”

For a while, Matthews invited buyers to meet dogs at a house in Arcadia she owned. Holly Pinedo met Matthews there in 2009, following up on a Puppyfind.com ad for Maltipoos.

“I’ve got the perfect dog for you,” Pinedo recalled Matthews saying, before carrying out a tiny white puppy priced at $1,600. Pinedo asked to see the parents, which the woman had agreed to do on the phone earlier. “She goes, ‘Well, you know, the dogs are kind of resting right now. I’d prefer not to bring them out.’”

Her daughter had a bad feeling, but Pinedo was distraught over losing her Australian shepherd a few days earlier and was eager for a new dog. At home, the pup soon fell ill.

Medicine that Pinedo said Matthews gave her after she purchased the puppy caused it to violently vomit. A vet advised Pinedo to return the dog, which she had named Lacey.

“If I gave her back, Lacey didn’t stand a chance,” Pinedo said. Pinedo nursed the dog back to health and won $1,350 in a small-claims lawsuit she filed that year against Matthews stemming from the purchase. But over her 15 years, Lacey has had a slew of health issues that Pinedo said have cost $30,000. “She’s never been 100% right.”

Jason Palmer quickly learned the French bulldog he bought in 2012 from “Jessica” in a CVS parking lot in Corona had parasites and a piece of plastic obstructing his intestine. The puppy, whom he named Franklin, aspirated on his vomit and developed pneumonia. Franklin survived, but Palmer said the dog was in and out of the vet for nearly a year. In 2015, Palmer settled a civil lawsuit against Matthews for $10,000.

“She’s putting people and animals through hell,” said Heather Madla, who bought a sick shih tzu from Matthews in 2011.

Matthews’ attorney did not answer specific questions about the allegations, but said customers rarely bought sick puppies.

“Over the decades, I’m sure there were some sick puppies, but very few and far between. Obviously, people/customers get very upset — and rightfully so — if a puppy becomes sick,” Cole said. “It is unavoidable, but I’m certain for every one sick puppy, there were many, many more that were not.”

Hundreds of dogs bound for California in recent years were from one of Iowa’s most infamous dog farms. It sits at the end of a long driveway behind a thick row of trees in the small rural town of West Point, where breeding dogs and puppies outnumber residents nearly 2 to 1.

USDA inspectors drove up one Tuesday in March last year for a routine visit, as they’d done dozens of times over the decades, ready to take notes and photos as they walked the kennels housing 718 dogs.

They found a Bernese mountain dog licking a bloody incision on her abdomen where she’d recently been artificially inseminated, according to their USDA inspection report. Most of her teeth were encased with a thick brown buildup, her gums swollen and red. Nearby, a poodle mix limped to avoid putting pressure on a leg wound stained with dried and fresh blood. A Boston terrier squinted, her left eye cloudy and eyelids red. An oval abrasion on a French bulldog’s ear was rimmed by crusty discharge. Several more dogs had matted coats. The USDA said it doesn’t keep “acquisition and disposition” records, which could show whether puppies from those dogs went to California.

None of them were getting medical attention, inspectors noted.

It was the latest in a steady stream of federal violations against the owner, who started breeding dogs in 1986.

“Steve Kruse basically is the kingpin of Iowa puppy mills, and probably well beyond that,” said Joe Stafford, a director at the Animal Rescue League of Iowa, referencing the scale of Kruse’s business operations. USDA inspectors brought a state trooper to site visits out of concern for their safety, according to written declarations of USDA officials reviewed by The Times.

After the March visit last year, Kruse’s USDA license was suspended for 21 days.

It didn’t stop the churn of puppies. The day Kruse, 72, was served with the punishment, a veterinarian for Kruse and his partner examined 30 puppies bound for California, and determined they were good to go, travel certificates from the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship show. More puppies got the green light to travel after the suspension was lifted. The puppies were whelped by Kruse’s business partner and former employee who sells the litters from Kruse’s breeding dogs under his own license, which had not been suspended.

On paper, they were bound for Companions To You in Covina. In the past, other puppies from Kruse’s compound were sent to Andy P of Pups R Us in Mira Loma and Michelle Simpson of Forever Pets in Norco, according to the travel certificates. But The Times could not find companies or people with those names.

Mindi Callison, head of the Iowa-based anti-puppy-mill nonprofit Bailing Out Benji, regularly pores through travel certificates. She said she began noticing dogs were “disappearing” to California, at least on paper, in June 2020. She complained to the Iowa and U.S. departments of agriculture about one of the mystery buyers — Andy P.

1

2

1. Mindi Callison, founder of the nonprofit Bailing Out Benji, with her dog Eleanor. 2. Eleanor, who came from an Iowa puppy mill, recently died. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

“Hundreds of Iowa puppies have traveled to this unlicensed broker who, in turn, flips the puppies on websites,” she wrote to Iowa officials. She implored them to contact the breeders and the vets who signed the certificates to “make sure the puppies are safe.”

The Times linked the three aliases listed on travel certificates to Matthews.

Phone numbers for Matthews provided by her associates, as well as one on court records and a business license application filed by Matthews, were listed on certificates of veterinary inspection for two of the aliases — Andy P and Michelle Simpson. Using microchip numbers printed on the forms for Michelle Simpson and the third alias, Stephany Weatherall of Companions To You, reporters found three buyers who reviewed photographs of Matthews and identified her as the seller. The travel certificate for the Boston terrier delivered to her garage listed Pups R Us and the phone number Matthews provided in court records.

All together, the three aliases were listed as the destination for more than 900 dogs since 2019 from at least six states, The Times found. Many came from Kruse’s dog farm, according to travel certificates.

Less than two weeks after Kruse’s suspension was lifted last year, USDA inspectors visited again and noted that the paws of more than a dozen dogs, including Yorkies and poodles, were slipping through gaps more than an inch wide in the raised flooring of their enclosure. Three bulldogs had mucousy, reddened or cloudy eyes. He was cited, but allowed to continue operating.

The Times attempted to interview Kruse at his flagship site in West Point, where a sign warned of guard dogs and instructed visitors to call before entering. A man who answered at a phone number listed on the sign hung up when reporters introduced themselves. Shortly after, a sheriff’s deputy called reporters in response to a trespassing report.

“I d rather talked to the devil because he is. More honest,” Kruse said in a text message to The Times about a week later. “By the way you or your people are not to go near or set foot on any of properties or you will be arrested.”

Kruse’s name isn’t on the travel certificates for puppies coming into California. USDA records show he has an arrangement with the former employee, Brian Lichirie.

Kruse gave a piece of his sprawling farm, including whelping sheds, to Lichirie, with Lichirie later using the annexed property to obtain his own USDA license, according to USDA and county property records. Kruse now transfers his pregnant dogs to Lichirie, who whelps the puppies and raises them until they’re weaned. Lichirie sells the puppies and returns the adult dogs to Kruse, according to USDA records reviewed by The Times that described the arrangement.

The partnership allows Kruse to breed dogs that end up in states such as Connecticut that prohibit pet stores from buying from breeders or brokers cited for certain animal welfare violations, according to Callison, who in March complained about the practice to the Connecticut Department of Agriculture. Lichirie, who’s had a license for four years, has a clean USDA record. Lichirie did not respond to calls, texts and a visit to his Iowa home requesting comment.

Connecticut officials reviewed records of at least two pet shops that listed Lichirie as the seller of puppies and found “no proof” they originated with Kruse, according to state investigative reports. However, the report cited USDA paperwork that Kruse frequently passes pregnant dogs to Lichirie, and advised the pet shops to “use caution” if purchasing from Lichirie.

Jerry Couchman, who said he is Kruse’s veterinarian and runs his own breeding facility, told The Times in a brief interview that he visits Kruse’s compound every other week to check the puppies being sold and walk the kennel to document health issues before inspectors visit.

After a few minutes, Couchman said he didn’t realize he was talking to reporters, who had identified themselves in the voicemail he returned, and left a business card on his front door.

“They’re the owners, they’re the ones who do the shipping,” Couchman said of Kruse and Lichirie. “I just take care of the health papers. I’m responsible to the USDA, and the state government … and not to you.”

Across the Midwest in any given week, unmarked white vans dart between breeder kennels, broker facilities and veterinarian offices, where health certificates are signed by the dozen.

Tiffanie Kurz, a broker in Frankford, Mo., whose name appears on dozens of travel certificates with nonexistent destination addresses in California, told The Times she was concerned about where those puppies were going. She said she sources puppies from about five breeders who each have fewer than 100 breeding dogs.

“It does bother me that somebody’s out there with intentions that aren’t right,” she said, toting two white puppies outside a building where she keeps them, a few feet from her home. She said she would compare records provided by The Times against her own, but then did not respond to follow-up queries.

Companions To You in Covina ordered four dogs from Iowa breeder Heather Anderson in June of last year. In a phone interview, Anderson said that when someone buys a puppy from her online, the buyer information populates a travel certificate, and she arranges the health check and transportation. Once the puppy is on the transport truck, she said she doesn’t know where it goes.

Anderson didn’t recognize Matthews’ name or the alias listed on travel documents, and declined to check her records.

“This literally is what kills me and what makes it not fun anymore. Because everybody is looking for a wolf in a sheep shack,” she said. “And there’s a lot scarier demons out there than somebody who uses an alias name to buy some puppies.”

Anderson said she is leaving the breeding business due to what she described as over-regulation and an increasingly “entitled” public.

“They all think we should have all our dogs in our houses,” she said. “That’s what hoarders do. We have very clean, very tidy facilities that we keep these dogs in. … Shelters are a hell of a lot nastier.”

Kurt Moeller — a breeder who said he sells exclusively to Select Puppies, a large broker in West Point listed on travel certificates with California destinations that don’t exist — said he doesn’t deal directly with pet buyers.

Moeller stepped outside a long metal structure with rows of caged, barking dogs, his ears buried under noise-reducing headphones. He closed the door behind him, muffling the sound and smell.

“I don’t know nothing about that,” said Moeller, whose 145-dog kennel sits on land he co-owns with Kruse. “I don’t want to know about that.”

Retired Missouri pet transporter Debbie Earnest said one of her drivers was perplexed when she followed her GPS to the Bay Area address listed on a health certificate and found an empty lot.

It wasn’t just the address that didn’t exist. The names listed on forms for the buyer — Ran Xu and Jonabelle Semana — also were “fictitious,” she said. The transporter was directed to another address, this time a home in a residential neighborhood a town over, in Union City.

The Times linked Earnest’s deliveries to a Bay Area real estate agent, Jessica Yang. Her name and the Union City delivery address had appeared on travel certificates until 2019. At times, the same phone number was used on travel certificates for Yang and the two aliases.

Tiffany Tuazon said she paid $1,500 for the Maltipoo she found Yang and her mom selling on Craigslist before Christmas 2018.

The puppy, Harley, soon fell ill.

“I thought she was actually going to die,” Tuazon said. Harley eventually recovered, and Yang and Grace Chang were ordered by a court commissioner to pay Tuazon more than $500 in vet bills. Yang and Chang did not respond to requests for comment.

Suzanne Bauley and the name of her former Malibu pet store, Millionaire Mutts, are listed as the destination for 380 dogs from at least six states since 2020. Some came from Daniel Gingerich, the Iowa breeder who hid dead dogs in horse stalls, according to USDA records.

Phone numbers The Times used to reach Bauley are listed on various websites and social media advertising puppies for sale. “We are a small family breeder,” a website for Cali Cavapoos says. “The parents are our pets and live in our home.”

When reached by phone on a number listed on some of the travel certificates, Bauley denied ordering those dogs, saying she no longer breeds and only imports dogs “from Korea.” She said someone must have used her name and phone number without her knowledge. She would not provide contact information for the person she suspected.

“Why don’t you call the owner of the dogs? Track the microchips. I don’t f— know,” Bauley said.

The Times tracked down the owner of one puppy whose microchip appeared on a travel document for Millionaire Mutts.

A Los Angeles nurse who asked not to be identified said she bought a puppy two years ago and provided screenshots of text messages in which Bauley provided her name and number to send a Zelle payment.

The nurse recalled Bauley saying that she bred the Yorkiechon, a four-pound, toy-sized Yorkshire terrier and bichon frise mix.

The dog came from an Ohio broker, according to a travel certificate filed with the state of Ohio that included 18 other puppies bound for Millionaire Mutts.

“She ended up having Crohn’s disease,” the nurse said. “She’s on medication for life. She’s on a special diet. She has all this anxiety. We love her to death and we wouldn’t trade her for the world, but we’ve spent so much money.”

“We love her to death and we wouldn’t trade her for the world, but we’ve spent so much money.”

— Los Angeles nurse, on a puppy she bought from former Malibu pet store owner Suzanne Bauley

In the Central Valley, Alissa Peña’s family did extensive research before surprising her last Mother’s Day with a Bernedoodle.

They settled on a puppy advertised online by Bay Area Bernedoodles. Peña said they were willing to pay more for the dog, Jax, because they believed he was from a small, local breeder in San José. Plus, she said, the seller told them their new puppy was an emotional support animal.

But The Times traced Jax’s microchip and found he came from a high-volume breeding facility in Ohio.

“That’s appalling,” Peña said.

A week before they picked Jax up, travel records indicated the dog had been prepped to be flown across the country to the seller Kadee Vo.

The ranch-style home on a leafy street where Peña’s husband picked up Jax was the destination for more than 240 dogs since last year, travel certificates show.

Vo’s name is listed on travel documents in 2022 and 2023 for 670 other puppies destined for an address on a gritty industrial street lined with warehouses in San Francisco’s Hunters Point. That same address is used on business records Vo filed for SF Golden Retrievers. In all, Vo’s name and various addresses were listed on travel records for more than 1,900 dogs since 2019.

“We wouldn’t have purchased Jax or any dog if it wasn’t through a breeder,” Peña said. “We … didn’t want a sick dog.”

Even the birth date listed on the travel certificate, she said, is different from what Peña’s family said the seller, who identified himself to them as Randy, provided.

At Vo’s San José home, a man who said he was Vo’s brother refused to talk to reporters before driving off.

Reached by phone, Vo, whose full name is Randy Kadee Vo, disputed that he had taken delivery of that many dogs, but refused to say how many dogs he was importing from other states.

“It’s none of your business,” Vo said in May.

Shortly after, the SF Golden Retrievers website disappeared. In a follow-up call, Vo said he no longer sells dogs.

In the dark Norco garage, Abruzzo agonized over leaving behind dozens of animals, including the tiny Boston terrier he delivered.

As he left, he knew he would report what he had seen once he returned to Missouri and was out of earshot of his driving partner.

“If they remained in those conditions, there’s a good chance they were going to die,” he said.

Two days later, within hours of Abruzzo’s animal cruelty report, a Norco Animal Services investigator obtained a warrant to search the property and seize the animals inside.

Authorities took 42 dogs, including the Boston terrier, and 21 cats from the humid garage, which they noted was between 94 and 99.8 degrees that August 2021 day. It was at least the third time animals had been seized from the Norco garage. The dogs were taken to the city-run shelter in Norco, where most were adopted. One was stolen from the shelter. Matthews was charged with two felony counts of animal cruelty.

Some of the animals had “broken bones, broken teeth. There was feces everywhere. Some of these animals were sick,” a prosecutor said during one court hearing.

In a recent statement, Cole, Matthews’ attorney, said, “There was only one or two that were sick. While it was very hot because I’m told the AC broke, virtually all of the puppies survived, did well and any alleged illness was a very minor aspect to the criminal case.”

A judge ordered Matthews not to possess any animals while her case was being decided.

But aliases The Times linked to her continued to show up on travel certificates issued in Iowa, Missouri and Kansas.

Last summer, the niece of one of Matthews’ customers arranged a meeting to buy a dog in a Chino parking lot and instead alerted Times reporters. The niece said she was angered to learn that Matthews had duped her aunt into buying a puppy that, according to its microchip, had come from Kruse’s compound.

At the time, according to the niece, Matthews said her name was Jenny.

With the criminal charges pending and the order not to possess animals in effect, Matthews showed up with her hair fully tucked into a black headwrap, a COVID-style mask pulled down under her chin. She drove a PT Cruiser registered to a woman who said she had sold the car years earlier to a man The Times identified as Matthews’ boyfriend.

Matthews pulled a ratty puppy from the backseat, its tangled white fur stained brown around its face. “I was trying to brush her ‘cause she stepped in something,” she said, more yelping coming from inside the car.

A reporter asked the woman if she was Monique Matthews.

“No, I am not,” she said, before pulling the mask over her nose and mouth. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Monique Matthews tries to sell a dog in a parking lot despite a judge’s order not to possess animals.

She denied selling sick puppies as she quickly walked to her car, placed the puppy in the front passenger seat and drove off. Matthews declined to comment several times at court hearings after that and, through Cole, denied that she was the woman in the parking lot. When later provided a video of the encounter, Cole acknowledged that the woman sounded like Matthews. Six people who know Matthews reviewed a photo from the interaction and confirmed it was her.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said outside the courtroom less than two weeks after the parking lot meeting. She left and returned about 15 minutes later, wearing a cardigan draped over her head and hair.

Matthews arrived for another court appearance a few weeks later, in October, wearing a dark blue sheet over her head and a surgical mask. When a reporter approached her attorney in the hallway, Matthews stood a couple of feet away, the blue sheet fully draped over her face.

Eventually Matthews pleaded guilty to two counts of animal cruelty.

In July at the Riverside Hall of Justice, Judge Thomas Kelly sentenced her to 90 days of custody through a work release program, 200 hours of community service and two years of probation.

“This was an egregious situation,” Kelly said, noting that the animals were in a crowded, hot environment with no water. He said they were fortunate that a citizen, Abruzzo, reported the neglect.

“Thank goodness,” the judge said.

He added that as part of her probation, Matthews could not shelter animals “professionally.” The prosecutor piped in, saying he thought the order would apply to owning or possessing any animal.

Matthews stood facing the judge, her legs fidgeting throughout the hearing. The attorney representing her, Graham Donath, started to argue that she be allowed to keep her personal pets.

Before he could finish, the judge agreed.