Long before citrus reigned in Southern California, L.A. made wine. Lots of it

- Share via

Napa, Schmapa.

For the better part of a hundred years, as the wine historian Thomas Pinney has remarked, “California wine meant Los Angeles wine.”

Think I’m pulling your hollow leg? Not in the least.

The glory that now haloes the vineyard valleys of Sonoma and Santa Ynez, Alexander and Edna, the Russian River, and other dales and vales, once belonged to Los Angeles.

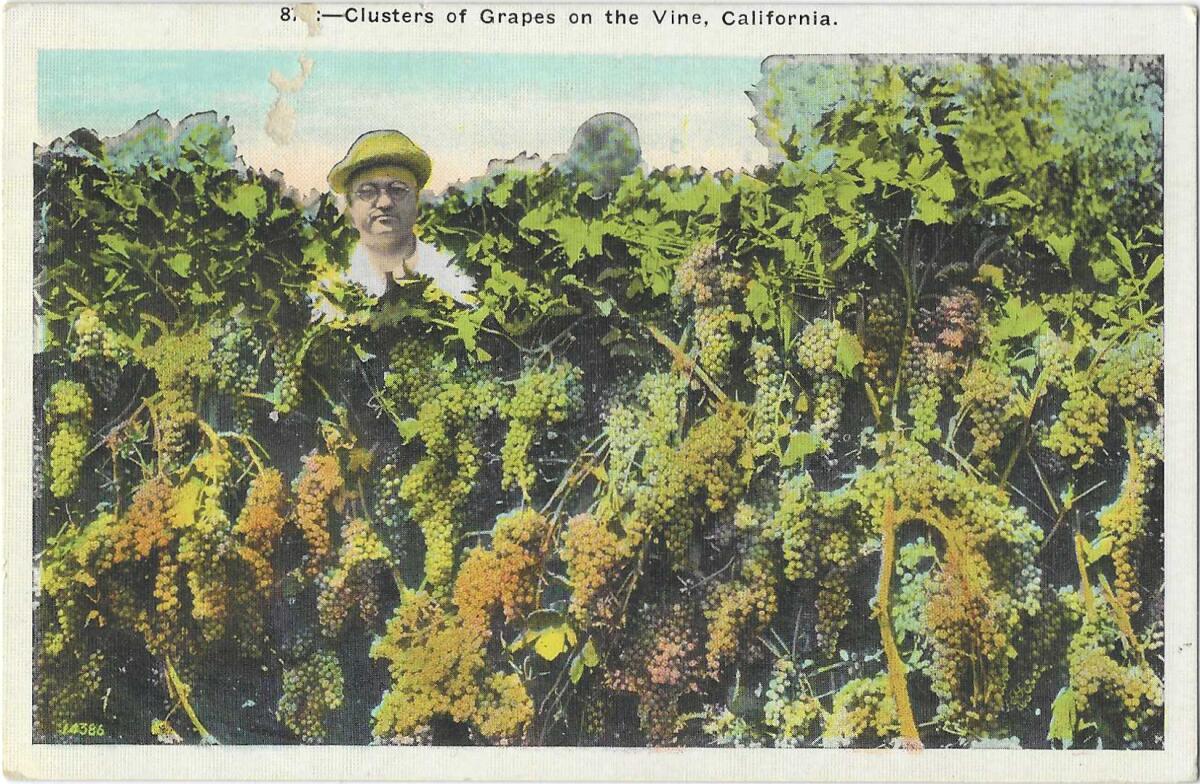

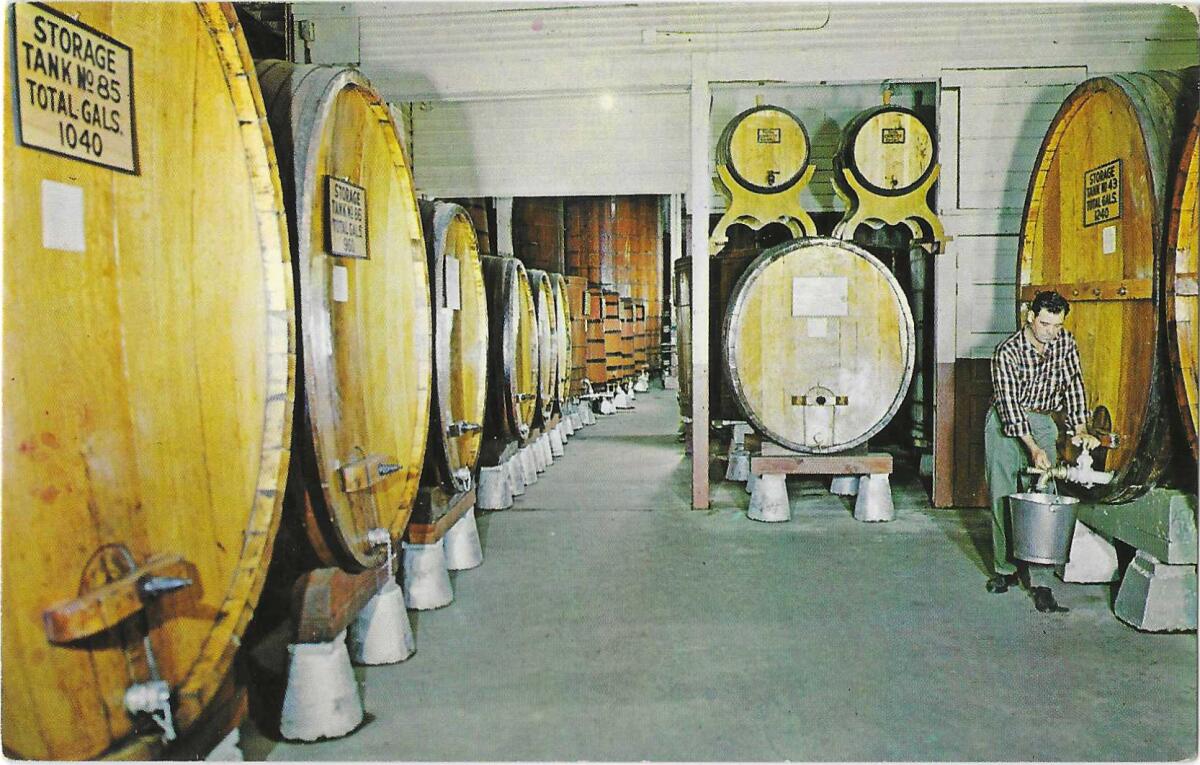

Years before the reign of King Citrus, dozens of wineries and more than a million grapevines made up an enormous L.A. cash crop. In 1869, when L.A.’s wineries were squeezing out as much as 5 million gallons, 3 out of every 4 Los Angeles manufacturing workers were earning their pay in some fashion from the wine business.

So supreme was the power of the vine that, according to Judith Gerber, co-author of “From Cows to Concrete: The Rise and Fall of Farming in Los Angeles,” that in 1854, the first Los Angeles city seal was just a cluster of grapes surrounded by leaves; it was used for more than half a century, until it was replaced with the current seal in 1905.

Now: Set the wayback machine to 100 years before then, when Spanish soldiers and priests were threading their way up here in Alta California, bringing with them, as The Times’ wine critic once wrote, “the cross, the sword, and the vine.”

For a while, the missions’ sacramental wine was shipped up from Mexico, but pretty soon vine cuttings were bundled and sent north too. St. Junipero Serra, the founder of the California missions, found the wine supply critical enough to write a letter from the San Gabriel Mission to his superiors on Oct. 27, 1783: “Many masses have not been said because of our lack of wine. We have plenty everywhere at present, except at this mission.”

Thus, a Spanish wine grape made a big splash in the New World, where it was known for a time as the Los Angeles grape, and enduringly as the Mission grape, one of the top crops at the San Gabriel and San Fernando missions.

Just about every culture has its own intoxicant, and native Californians had already long concocted pispibata, a wooze-inducing substance from native cherries. California had a native grape, but neither the Indigenous Californians nor the arriving padres found it palatable.

Like the “Mother Hass” avocado tree in La Habra Heights, the San Gabriel Mission’s vineyards provided the founding madre stock of much of L.A.’s emerging commercial wine industry.

The 1880 “History of Los Angeles County” declares, with a likely margin of error, that when the missions were secularized by the Mexican government in the 1830s, the padres told the missions’ Native American workers to destroy the grapevines, but they refused. In the same account, locals hacked up some vines for firewood.

Whatever happened, enough survived to beget L.A.’s secular wine grape trade. It became what the orange-tree-in-every-yard would soon be for gentleman farmers: a few grapevines grown for the family table, or eventually tens of thousands for profit.

One of these — more farmer than gentleman — was New Englander John Chapman. He was among the first Yankee Americans to show up in Southern California, a sailor-buccaneer whose industry and ingenuity impressed the Mexican officials. He was a dab hand at carpentering, doctoring, shipbuilding and grape growing. In 1826, he owned a house and several thousand grapevines in Los Angeles, shared with his Mexican wife, Guadalupe, and their 11 children.

You can determine L.A.’s seasons by our plant life. For example, right now, it’s jacaranda-blooms-stuck-to-your-windshield season. And to understand the Southern California landscape you see, you have to realize that, like you, it is probably not from around here.

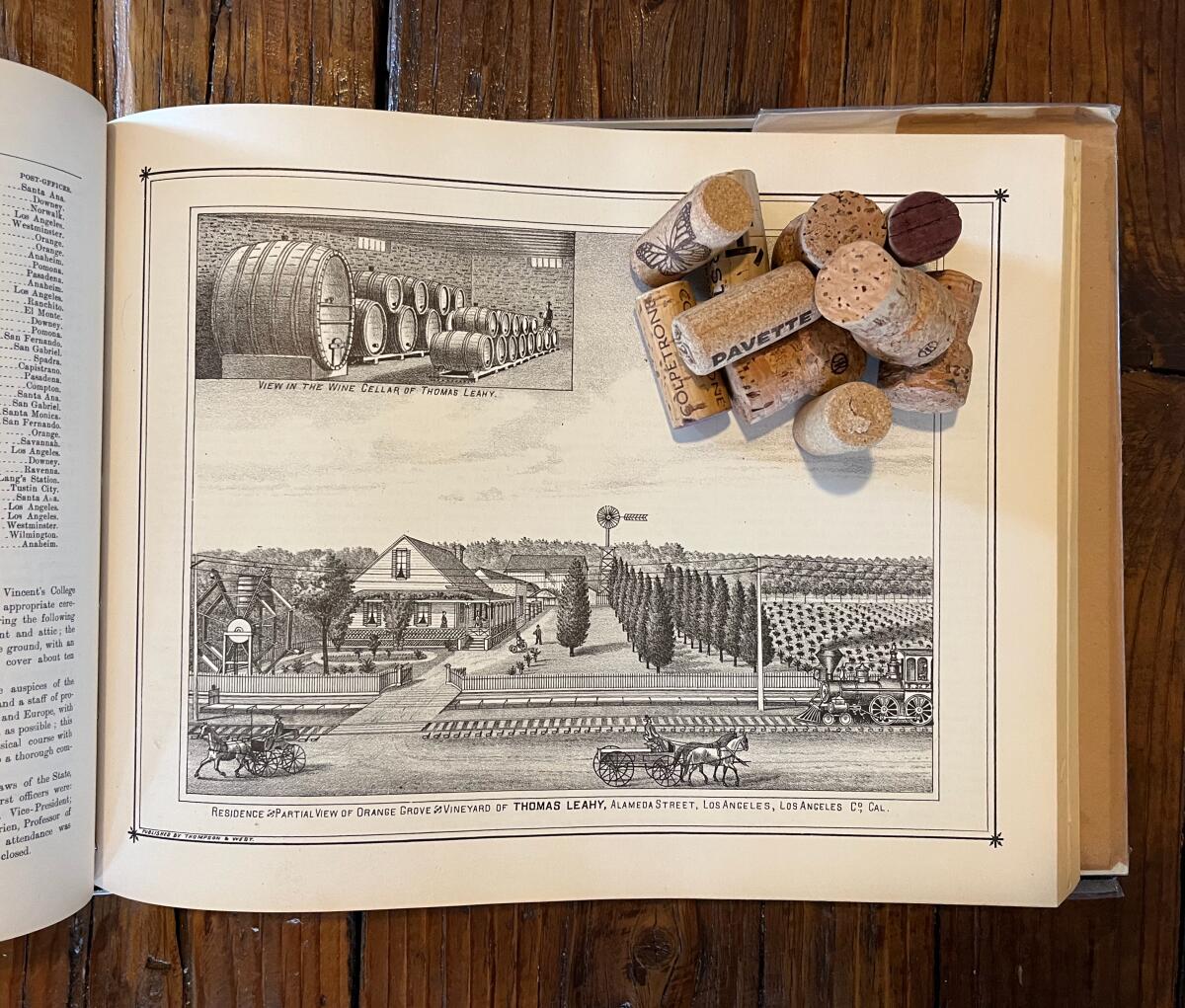

L.A. had a couple of dozen wineries by the 1830s, most of them along the west side of the L.A. River. In the 1860s, a man named Andrew Boyle began growing grapes on the unfashionable “flats” east of the river, and sold the wine under the “Paredon Blanc” name — the White Wall. We know the neighborhood as Boyle Heights.

Let’s take a moment here to define what that early “wine” was. The principal grape drink was aguardiente, a portmanteau meaning “burning water,” a brandy of considerable ferocity. Actual wine was a pretty basic plonk at first, unornamented by comments about bouquet or terroir, so cheap and so plentiful that it was often poured free with restaurant meals. The locals also favored a white fortified wine called Angelica.

Around 1857, vintner Manuel Requeña and future citrus tycoon William Wolfskill sent gifts of vino to President James Buchanan, packing red and white wine, brandy and Angelica; the winemaking Sainsevains brothers sent their own rudimentary sparkling wine to the White House. In a thank-you letter from “Washington City,” Buchanan thanked the freres Sainsevain and predicted a great future for California wine.

The San Fernando Mission had its own laudable vineyards, and in 1846, Spanish native Eulogio de Celis bought much of the mission land, lock, stock and grapevines, from Mexican officials. He and the Californio statesman and land baron Andres Pico made a wine that one visitor found to be “of good quality.”

Jean-Louis Vignes — his last name by happy chance means “vines” — arrived from France’s Bordeaux wine region in about 1831, and his riverside vineyards, where Union Station now stands, produced some hundreds of barrels a year. His history is muzzy: Either he hightailed it out of France on the sly, and his nephews, the Sainsevain brothers, scoured the world to find him, or he settled here and then invited his relatives to join him and prosper.

His name — Vignes — is still on a downtown L.A. street, as is “Aliso,” the name he gave his vineyard. So is “Mateo,” for Matthew Keller, an Irishman who grew grapes near Vignes’ and Wolfskill’s property. He called his the Rising Sun Vineyard, and in her book “Towers of Gold,” Frances Dinkenspiel writes that Keller was always taking up new viticulture technology to make his wine better.

Bauchet Street — address of the Men’s Central Jail — recalls Louis Bauchet, once a stalwart in Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, who began growing wine grapes in 1831.

Kohler Street was named for Charles Kohler, a German violinist who partnered with flutist John Frohling to make a California wine that made a splash on the East Coast. (Five years ago, the Daily Beast reported, Kohler’s great-great-grandson was reviving the label that Prohibition had killed off.)

San Pedro Street was once Vineyard Street. Sainsevain Street was eventually renamed Commercial Street, and Wine Street you know by the name Olvera Street, for the county’s first elected judge, Agustin Olvera. Azusa still has a Dalton Avenue, named for an energetic Englishman who, in the 1840s, bought up wide swaths of rancho land in the San Gabriel foothills and started up a winery and a distillery, among his many enterprises.

The hundreds of acres of the San Gabriel Winery — south of South Pasadena, west of Alhambra — supposedly had cellars that could hold a million and a half gallons, but according to books by Pomona College emeritus professor and wine historian Pinney, the company fell afoul of untrustworthy agents and critical consumers. One Philadelphia merchant disdained the port wine as “nothing but trash. I would not give it away, much less sell it to my customers.”

Even though, by the 1960s, the average Californian was quaffing two gallons of wine a year to his countrymen’s one, it took time for many Californians to cultivate what is called a sophisticated palate. In 1967, The Times related what happened to Robert Mondavi, a founding father of modern California wine. He was served a glass of boiling-hot wine in a restaurant — hot! When he complained, the waiter said, It’s supposed to be hot, and pointed indignantly to the label. See? “Haut Sauterne.”

The Gold Rush populated Northern California with drinking men, and L.A. wine was close by, plentiful, and at least relatively cheap. The year gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, a thriving vineyard in L.A. could bring as much as $1,000 an acre.

And then, some men who didn’t strike it rich with gold stayed on in Northern California to cultivate grapes, and others joined them. The prospering wine business — and threats like tariffs, temperance movements and disease — nudged the state to create a viticultural commission board, which still exists.

By 1859, L.A. County already had a cooperative founded by a vineyard society to manage the cornucopia of wine grapes cultivated and grown by French, Italian, German, Swiss and Spanish growers.

Some years ago, I ran across a song, published in the centennial year 1876, extolling “The Wines of Los Angeles County” in five rumtey-tum verses whose refrain goes, “For of all to be proud for which we’re endowed / And for which we’re to thank nature’s bounty / There are none anywhere to be found to compare / To the wines of Los Angeles County.”

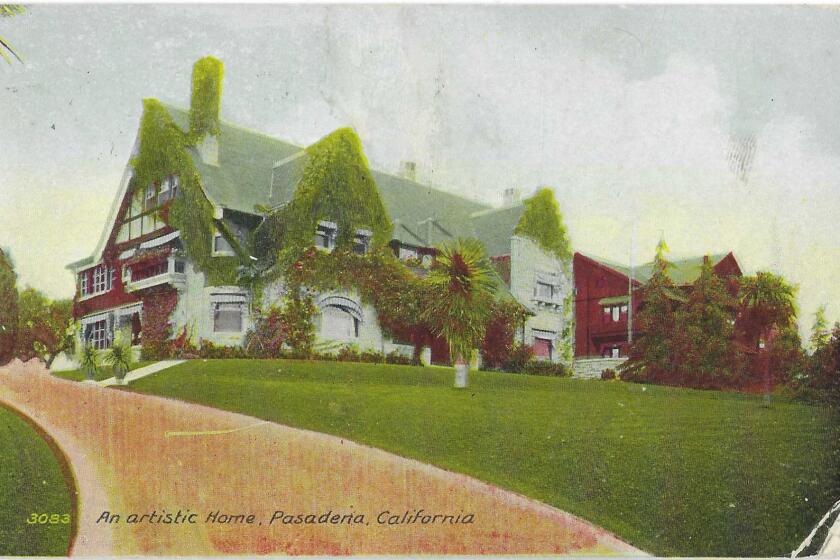

L.A.’s public beauty spots deserve a visit, by all means. But it’s the houses that surprise visitors and gratify us, even if they can only be glimpsed from a sidewalk.

By the 1880s, Northern California vineyards were far along their march to international renown with sophisticated varietal wines, and Los Angeles County was far along in making fortunes in citrus.

But first, they had to survive phylloxera — a kind of black plague for wine grapes, probably carried west from resistant East Coast vines. It walloped California’s wine grapes, and managed to make it from here to French vineyards, where it just about killed French winemaking, before vines were grafted onto bug-resistant American rootstock — a plan that just about killed French winemakers’ pride.

No such solution presented itself to save winemaking from Prohibition. All across Southern California, vineyards were torn up and plowed under.

Beginning in 1919, Charles Stern’s winery in Wineville, in Riverside County, was planting fruits and nuts instead, turning the winery into a cannery, and changing “Wineville” to “Windsor.” It’s now in an area called Mira Loma. The region east of Los Angeles had flourished in viticulture, and now its renowned wineries such as Italian Vineyard Co., east of Ontario, at one time the nation’s largest, were turning over vineyards to walnuts. By 1930, according to The Times, the vineyard founded by Secondo Guasti was still producing grape seed — and using it as hog feed. The Mission Vineyard Co. of Cucamonga sold off 1,600 acres to a fruit producer.

Some growers turned to table grapes and raisins, but federal agents were always on alert for anything that smelled of wine-in-the-bud. In 1931, The Times headlined a story, “Eight Face Grape Juice Trial Today.” The men were charged with conspiring “to distribute and well unfermented grape juice with the intention that it might later turn into wine.” Sure, it may be grape juice now, the feds argued — but heat it up and it could become wine! The men ended up with misdemeanor fines but got off on the conspiracy charges.

A very few wineries still made sacramental and medicinal wine, under very strict scrutiny. One of them was San Antonio Winery, which opened in 1917 on the banks of the river and survived Prohibition and the Depression and today is L.A.’s oldest producing winery.

As much as Prohibition or an impoverished economy, prosperity doomed the vineyards. Every month in 1967, Californians lost more than 11,000 acres of farmland and open space to subdivisions and shopping centers, and Los Angeles was pedal-to-the-metal on giving up farmland for housing.

Wineries still hang on here. New, young winemakers operate in the Antelope Valley. The Angeleno Wine Co. produces natural vegan wine not far from the San Antonio Winery, and Centralas does the same farther south, bottling its Crenshaw Cru. Byron Blatty Wines uses L.A. County grapes.

And then of course there’s Moraga Bel Air vineyards and winery in the city limits of L.A., about 14 acres of some of the richest and ritziest real estate around, half of which grows grapes.

It’s owned by Rupert Murdoch. He bought it in 2013 for a reported $28.8 million.

He learned that it was for sale when he read it in a story — in his own Wall Street Journal. Fifteen years before the boss bought the winery, the paper dropped into a review of California sauvignon blancs a tidbit about Moraga’s 1993 “meritage.” The “almost-impossible-to-find” wine was then an almost-impossible-to-afford $95. The Journal-ists adjudged it “remarkable.”

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.