It’s time to celebrate California Admission Day! Wait, what’s Admission Day?

Add this to your meager store of Millard Fillmore anecdotes: In 1850, his signature made California the 31st state, giving us a swell holiday that practically nobody remembers now.

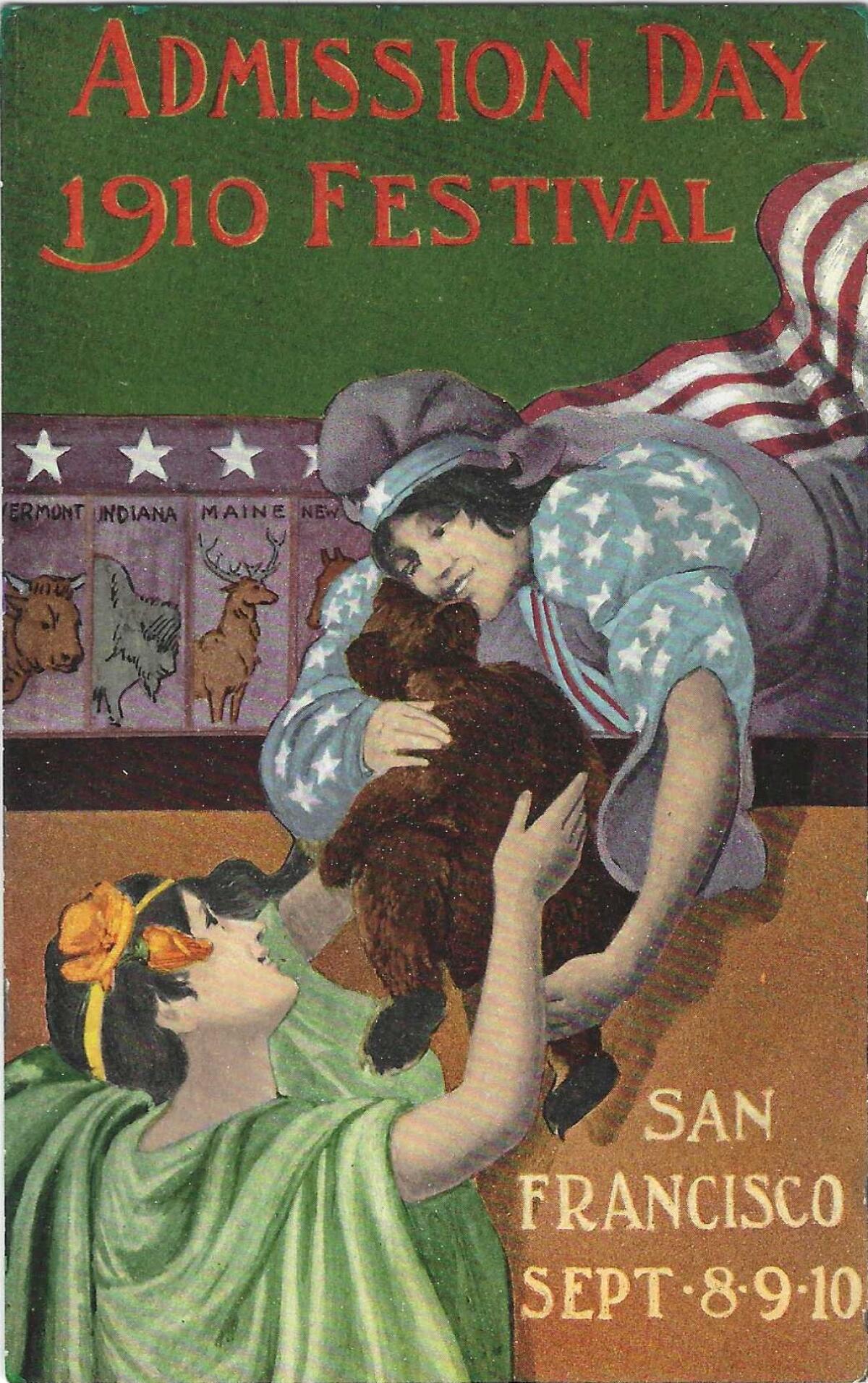

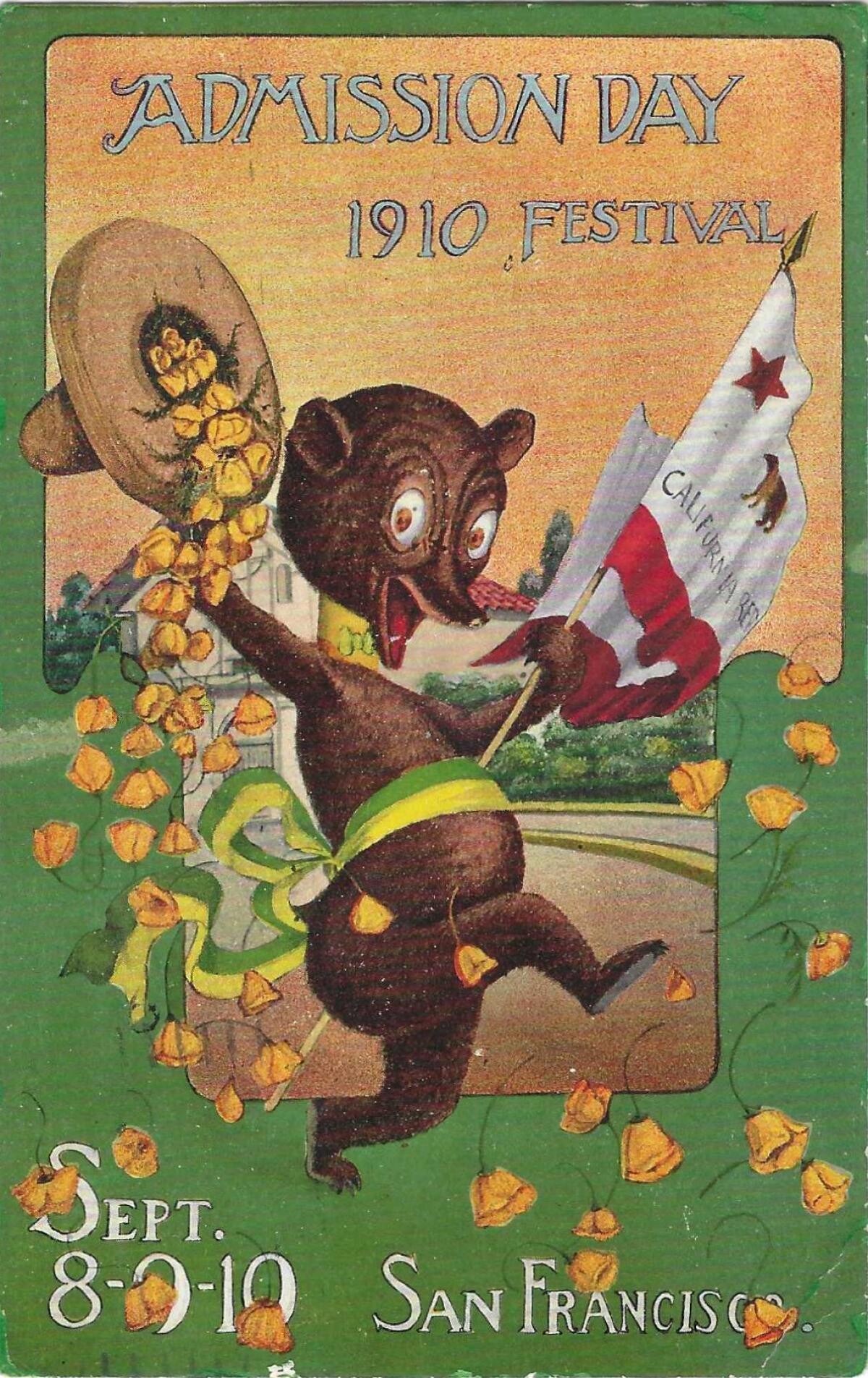

Admission Day, Sept. 9, used to be a gala-palooza in California. In some years, schools and state offices closed, and parades and pageants celebrated the state’s marriage with the United States. In 1937, in Santa Monica, bragged the L.A. Times, 200,000 people massed along the streets to watch “five miles of beauty and pageantry depicting periods of California history pass by.” For the 75th anniversary of statehood, in 1925, Orange County was “aflutter with Diamond Jubilee colors swaying gently in the California breeze.” On Sept. 9, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge hoisted the Bear Flag over the White House. Not personally, of course.

In early years, and for some time, there was a sanitized depiction of California’s “founders” mostly as white colonizers who came over on the Mayflower — not the immigrants of equally long standing here, nor the Native Americans, whose thousands of years in California were obliterated like native people themselves by the state’s cruel early laws and practices.

In his first go-round as governor, in 1976, Jerry Brown, a fourth-generation Californian, put a veto stop to a bill killing off the holiday. But the holiday was gutted in 1984 by Gov. George Deukmejian and turned into a flabby, floating day off work for state employees. In his second at-bat, Brown couldn’t restore the actual holiday, but he did proclaim that his predecessor’s erasure of the holiday was “convenient to some but in no way respectful of our storied founding. California’s early history is too often neglected in schools and among our citizens.”

California became a state in record time, and in an exceptional way. True then, true now: Gold has astounding uses, like buying a spot at the front of the line for statehood.

In the spring of 1846, after the U.S. couldn’t persuade Mexico to sell the land from Texas to the Pacific coast, it went to war with Mexico. A couple of months later, a few aggrieved Yankees in California — some of them loutish men who were in Mexican territory illegally, and isn’t that rich? — took over the town of Sonoma, patched together a flag of sorts and declared the “Bear Flag Republic,” which lasted for all of 25 days. (That flag is still today as offensive to some Indigenous and Latino Californians as the Confederate battle flag is to millions of Black Americans.)

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

During this whole tragicomic mishmash, with military and civilians strutting and chest-puffing, the U.S. used the war as one reason for imposing a military governorship over California.

And then, on Feb. 2, 1848, the war ended with the treaty of “peace, friendship, limits and settlement” signed by both nations in Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico, and half a million or so square miles of the West and Southwest, including California, came officially into U.S. hands. By happenstance — who says history has no sense of humor? — a scant nine days earlier, far to the north, a man building a sawmill southeast of Sacramento had discovered gold in the newly dug earth.

You know the Gold Rush story by now, the cataclysm and consequences.

What you may not know is this upshot: The United States had already desperately wanted California. It wanted to keep California from becoming an independent nation, a powerhouse on the Pacific. It wanted to keep it out of foreign hands; it was just in 1841, a year in very warm memory, that Russia had abandoned its outpost in Sonoma County. And now, of course, the U.S. wanted to keep all that gold.

So it was eager to rush California to the altar of statehood. Yankee California wanted a quickie wedding, too. Its “hack” was presumptuously convening a constitutional convention in September 1849, and even adopting a state seal.

In Los Angeles, founded for Spain and a part of Mexico for generations, we pronounce our Spanish-language place names in a unique way.

It’s the same familiar seal we use today, 172 years later: the 31 stars for the 31st state California wanted to become; the enthroned Minerva, Roman goddess of wisdom; the motto “Eureka” (“I have found it,” from the Greek); the gold miner; the mountains; the California grizzly bear — which we efficiently slaughtered to extinction about a hundred years ago.

Who designed this seal? A man named Robert S. Garnett, and although he’s been dead for 160 years, he made the news last year. He was a U.S. Army major in Monterey during the constitutional convention, and in 1957, a plaque to his memory was installed there by a local United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Yes, the Confederacy. The Virginia-born Garnett switched sides and became a Southern brigadier general and was killed early in the Civil War.

In 2017, after the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Va., the Monterey County Weekly reported that local civil rights activists got the plaque removed. A much less fulsome marker was put in its place, but in June 2020, someone carried off that marker, too, and left a message on cardboard: “Celebrate real heroes. No place of honor for racists.”

The new Constitution disenfranchised the bulk of California’s non-white, non-male population, so no surprise that it was approved in November 1849, by a soon-to-be-typical low voter turnout — something under 20% — and California’s new “senators” went east to lobby for statehood.

Other states would have to go through apprenticeships, a purgatory of being territories before states, like Arizona, Oregon, Utah. California went to the head of the line — but not without a fight.

Making California a state would mess up the fragile federal formula balancing slave and free states. Most Southerners in Congress, of course, wanted their “peculiar institution” exported to the West. The abolitionists wouldn’t hear of it.

Loads of books have been written on the monster battle waged in Congress, of which California statehood was the key that could pull down the whole wobbly edifice. A Mississippi senator pulled a pistol on a Missouri senator. Such Senate giants as Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, and Abe Lincoln’s future debate adversary Stephen A. Douglas, nudged and cajoled.

With exquisite timing, a president who didn’t much like the Compromise of 1850 died of some ugly digestive complaint, and your friend and mine VP Millard Fillmore became president and pretty promptly, on Sept. 9, 1850, signed the compromise — a temporary and flimsy thing that also created the noxious Fugitive Slave Act even as it made California a state.

It also allowed California to make up its own mind about slavery. The state already had: Partly because gold miners didn’t want the competition of free slave labor, California was from the get-go a free state, although with vile exceptions like its own fugitive slave law.

The statehood news didn’t reach California until Oct. 18. It had to travel by ship from Washington, D.C., overland through Panama, to a ship sailing up the Pacific coast.

The official documents of statehood were carried by 19-year-old Mary Helen Crosby, whose father had been a member of that first Legislature. Aboard ship, she kept them under her pillow at night. Riding mule-back across the Isthmus of Panama, she wrapped them securely inside her blue silk umbrella.

The mail steamer reached San Francisco on Oct. 18, 1850, flying flags and bright colors, and an enormous banner announcing, “California Admitted!” Mary Helen Crosby was the first off the ship, with her umbrella stashed with documents.

The next morning, California’s first civilian American governor, Peter H. Burnett — elected the year before, in cocky anticipation of statehood — set out from San Francisco by racing stagecoach for San Jose. “As we flew past on our rapid course, the people flocked to the road to see what caused our fast driving and loud shouting, and, without slackening our speed in the slightest degree, we took off our hats, waved them around our heads, and shouted at the tops of our voices, ‘California is admitted into the Union!’ ”

And so began that chapter of what Walt Whitman called “the flashing and golden pageant of California.” Come Sept. 9, go ahead and party like it’s 1850, and you’re a white man with a big, juicy placer mining claim!

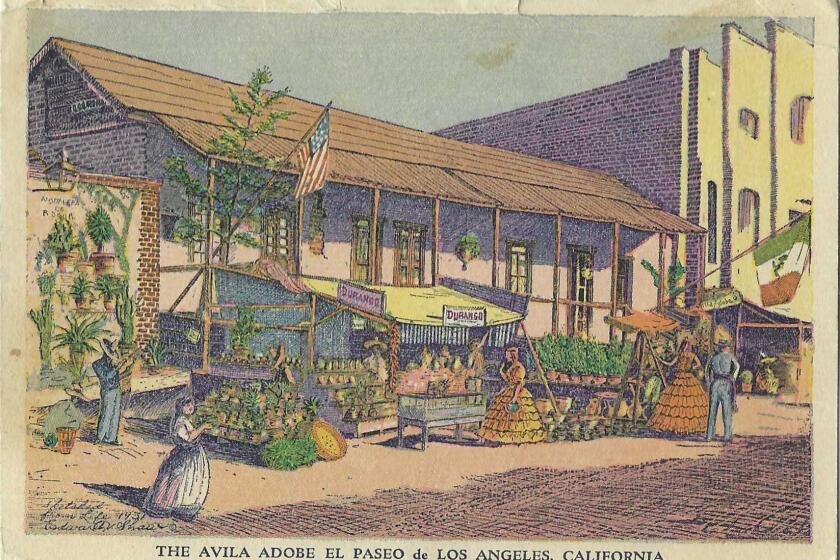

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.