Column: Progressives have ruined San Francisco. Just ask this heiress

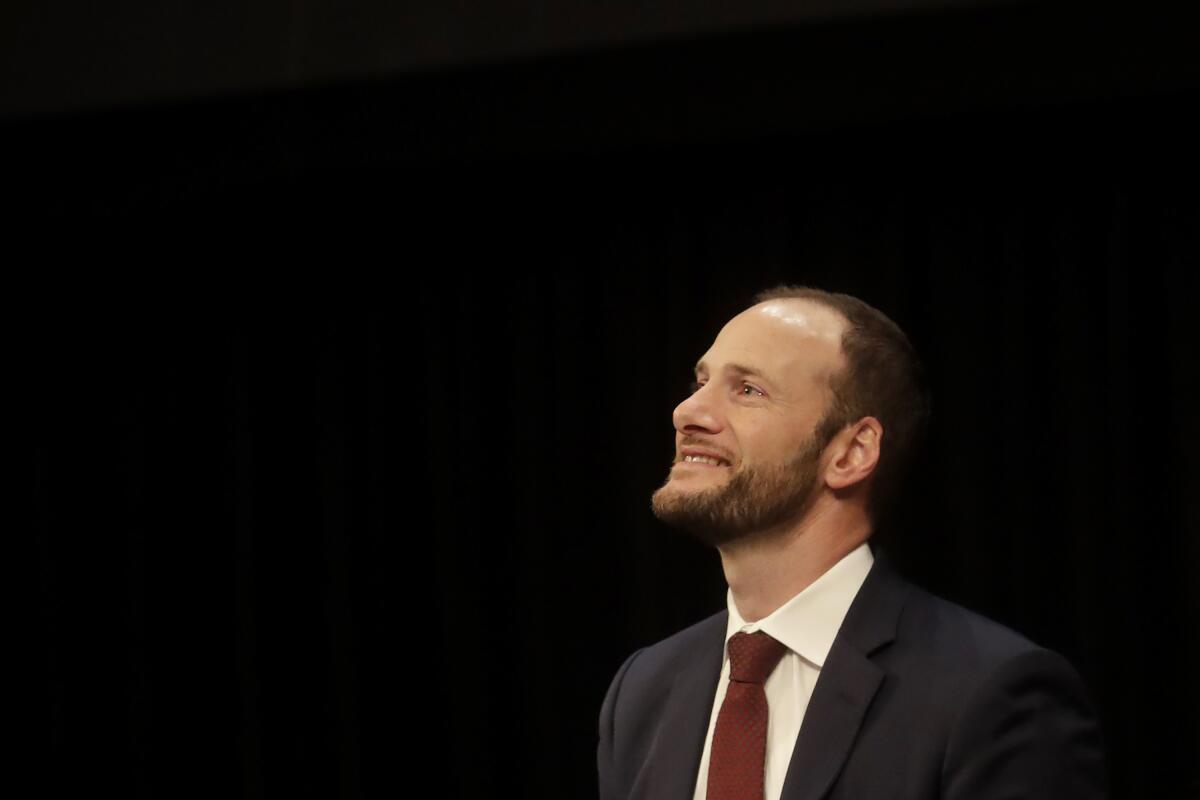

Say what you wish about the recall last week of Chesa Boudin, San Francisco’s liberal district attorney, it has been a gift for pundits searching for signs of a pushback against progressive criminal justice reforms.

“Most San Franciscans just realized that doctrinaire progressivism had become a suicide pact,” wrote Daniel Henninger of the Wall Street Journal, declaring an end to “a major city’s long transition to flowers-in-your-hair progressivism.” James Hohmann of the Washington Post labeled Boudin’s defeat as “the latest wake-up call for Democrats, who have lost the public’s trust on criminal justice.”

But the prize goes to Nellie Bowles, who weighed in with a nearly 8,000-word screed in the Atlantic, calling her former home town a “failed city” and ascribing its decline to “progressive leaders” and their “left-wing values.”

In San Francisco the word developer is basically a slur.

— Nellie Bowles, in the Atlantic

More on Bowles and the Atlantic in a moment. But first, some perspective on the election. There are few signs, if any, that voters are actually “fed up” with criminal justice reform, as Bowles would have it, whether in San Francisco specifically or the Bay Area generally.

In Alameda County across the bay, Yesenia Sanchez is poised to win her race for sheriff without facing a runoff, despite espousing progressive reforms not dissimilar from Boudin’s. Diana Becton, another progressive, appears to have won a second term as Contra Costa D.A., while civil rights attorney Pamela Price will head to a runoff for Alameda County D.A. with a sizable lead.

Boudin was saddled with distinctive negatives. These included clumsy political skills that led him to make easily caricatured public statements. He won election in 2019 by a razor-thin margin, marking him from the first as a vulnerable officeholder.

(As he told followers Monday, thanks to the peculiarities of recall voting, he actually received more votes this time around — that is, “no” on the recall — than he did in his original win.)

Boudin was targeted by real estate developers and Realtors, who contributed to a war chest of some $6.4 million, more than double the sum raised to oppose the recall.

The general public, as it happens, approved of many of Boudin’s signature policies, with majorities queried in a mid-May poll supporting his efforts to protect worker rights and review past cases for possible wrongful convictions. Pluralities in the poll supported his commitment to not charge children as adults and end the practice of cash bail.

The election-night returns showed Boudin losing handily, leading to reports that city residents had “voted overwhelmingly” against Boudin by more than 60%. Yet the latest, near-final tally shows that about 55% of those casting votes chose to turn Boudin out, but fewer than 45% of registered voters cast any vote. In other words, the recall vote amounted to 24.6% of San Francisco voters, which is less than “overwhelming” any way you cut it.

These data points don’t fit the preconceived narrative that is the hallmark of cheap punditry, which brings us back to the Bowles analysis. A former New York Times reporter now contributing to the Substack blog run by her wife, the conservative commentator Bari Weiss, Bowles described the Boudin recall as a citizens’ reaction to crime, a surfeit of homeless people, lots of dirt and grime, and loopy left-wing city officials.

Bowles’ bill of particulars wasn’t too different from many other analyses striving to make sense of the recall vote. One line in her article did catch my eye, however. It was Bowles’ apparent attempt to portray herself as the offspring of a working-class San Francisco family dating back six generations by mentioning that at the time of the Gold Rush “my German great-great-great-grandfather worked at a butcher shop on Jackson Street.”

I happen to know something about Bowles’ ancestor, because I’ve learned about him in the course of researching my forthcoming book, a history of California.

The California dream has always been a bit of a myth, but so is the notion that it’s coming to an end.

He was Henry Miller, and he didn’t labor in a butcher shop for long. By the early 1870s he was one of the richest men in California, a land baron who was known for exploiting the labor of itinerant homeless men to build a fortune in farming and cattle ranching. (Another Miller descendant, via a different branch of the family tree, is Tucker Carlson.)

Miller’s name doesn’t appear in Bowles’ article, nor do his wealth-building practices. A witness before a congressional committee in 1914 labeled Miller’s practices, which included monopolizing water rights in the Central Valley by threatening their rightful owners with expensive lawsuits, “a cause of social unrest.”

Miller established what was known as the “dirty plate route,” through which he let it be known that a tramp could get a free meal at a Miller rancho, but only one meal and only from an already-used plate. In this way he kept a steady stream of cheap labor moving through an empire that grew to more than 1 million acres. The Miller empire lives on today as Bowles Farming Co., a direct descendant of his old firm, Miller & Lux.

The real issue with Bowles’ depiction of the decline of San Francisco isn’t her family history. It’s the use of cherry-picking to create a misleading picture of conditions in San Francisco, the causes of its ostensible “failure,” and how they’re linked to the recall of Boudin. I reached out to Bowles for comment via Weiss and the Atlantic, but she didn’t respond.

The Bowles piece is another installment in the Atlantic’s “death of the California dream” genre, which I reported on last year. The Atlantic risks getting addicted to these yarns because of their popularity among non-Californians, in the same sense that the first taste of human blood has been reputed to turn African lions into incorrigible man-eaters.

Like that earlier piece, Bowles employs exaggeration and special pleading to make her case. She calls petty crime “rampant” and offers anecdotal evidence to prove it: The antique store where she bought her wife her wedding ring was “ransacked at the end of December,” she reports. She cites car break-ins and shoplifting, and quotes representatives of CVS and Walgreens complaining about retail theft.

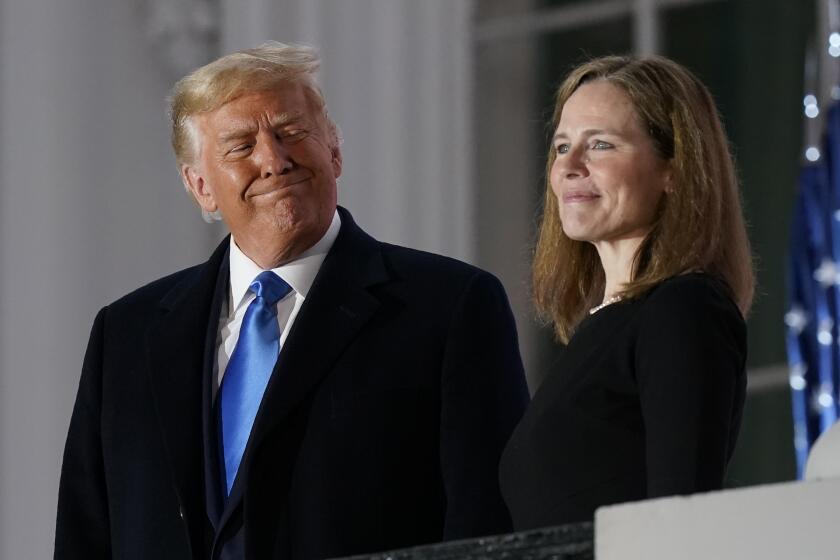

Trump’s legacy rests not on his policies but on the right-wing judges he placed on the federal courts.

Yet San Francisco Police Department statistics don’t indicate that the city is beleaguered by a crime wave. So far this year, burglaries and robberies are down from the same period a year ago, and both were lower in 2021 than in 2020.

Motor vehicle thefts are at about the same level now that they have been since the beginning of 2020; that’s bad, obviously, if it’s your car that’s been stolen or subjected to a smash-and-grab, but not exactly a new phenomenon in a city where on-street parking is the norm in many residential neighborhoods.

As for larceny theft, the category that includes shoplifting, it surged in 2021, but looks to be running at a slightly lower rate this year. In any event, it’s about 25% below the pre-pandemic levels of 2019 and 2018.

In any case, as my colleague Sam Dean documented, shoplifting statistics are notoriously unreliable. They appear to be wildly exaggerated by the industry and retail chains, and often wielded as an excuse by chains to close stores that are unprofitable for other reasons.

Bowles dismisses the narrative told by the real numbers by remarking that “you can spend days debating San Francisco crime statistics and their meaning, and many people do.” She acknowledges, too, that the city “has relatively low rates of violent crime, and when compared with similarly sized cities, one of the lowest rates of homicide.”

None of this is to say that perception is entirely divorced from reality. Let’s accept for the purposes of argument that the residents of San Francisco believe the place is going to hell. If that’s so, why? One answer may be the atrocious performance of the San Francisco police.

The department’s clearance rate, which already was one of the lowest in the country, fell last year to the lowest in a decade, with only 8.1% of reported crimes leading to an arrest. Some of the SFPD’s defenders, including Bowles, argue that the cops simply assume that, as a liberal, Boudin wouldn’t prosecute the culprits they arrest, so they don’t bother. But since they’re arresting fewer than one in 10 perpetrators, how would those supporters know?

Many ills Bowles and other critics ascribe to left-wing politicians and progressivism running wild in San Francisco aren’t even due to city initiatives.

Now Florida Gov. DeSantis wants to strip medical care from transgender children and adults.

Boudin was blamed for treating drug possession as a misdemeanor rather than a felony, but that was the mandate of Proposition 47, which passed overwhelmingly statewide in 2014, as Bowles acknowledges. Voters handily rejected an attempt to roll back some of Proposition 47 in 2020.

Drug deaths are up in San Francisco, but as Bowles acknowledges, that’s an artifact of the nationwide opioid crisis, not of local politics.

What does Bowles see as an answer to the city’s maladies? Less neighborhood opposition to new real estate construction. (“In San Francisco the word developer is basically a slur,” she writes.)

An oft-cited manifestation of the city’s paralysis is the constant battling between residents and real estate developers.

Among her examples of foolish NIMBYism is neighborhood resistance to a plan for 63 housing units on a tract that was a flower farm, which locals wished to see repurposed as a community garden and market. Bowles sneers at this as “a kind of banjo-and-beehives utopian fantasy,” whatever that means.

Anyway, the developer is proceeding with plans to put 63 housing units on the site. Bowles quotes a local lawyer observing “you could house 50 kids and their families on that site.” That may be true, but since the construction cost will be almost $1 million per unit, one can imagine that those families won’t resemble those that would be homeless if the development didn’t exist.

Like other critics of the municipal liberalism in San Francisco, Bowles is heartened by what she sees as the public recapturing its voice and rising up to turn the far-lefties out. Does that square with her contempt for those standing in the developer’s way?

No, but it gives the game away. Conservative pundits love to promote “free speech” and public activism, unless it’s directed at people of their class, like developers and those who think the right way to deal with drug addicts is to throw them in jail. If the Boudin recall really reflected the forces they praise, San Francisco might well turn into a different city. It might be better, but the question would be: Better for whom?