Column: A Faulkner classic and Popeye enter the public domain while copyright only gets more confusing

Last year, it was Mickey Mouse. This year, Popeye the Sailor joins Mickey as a new entrant to the public domain — that is, shedding his core copyright protections on Jan. 1.

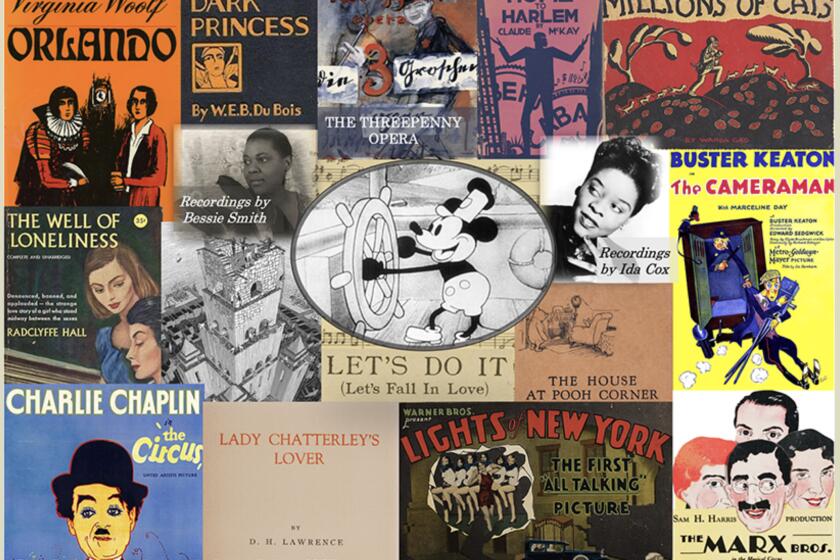

He’s merely the most familiar cultural artifact to enter the public domain on Wednesday. But as Jennifer Jenkins, co-director of Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain notes in her indispensable annual roster of newly public works (posted this year with co-director James Boyle), Popeye’s initial appearance in print is among thousands of culturally and artistically significant works to become copyright-free. That means they become available for anyone to copy, share and expand upon without paying their creators for rights.

This year’s treasure trove includes literary works originally published in 1929, meaning their 95-year copyrights expire on New Year’s Day. They include William Faulkner’s novel “The Sound and the Fury,” in which he began to perfect his literary style and his gloss on racial and social stratification in his native Mississippi; Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms”; and Virginia Woolf’s essay “A Room of One’s Own.”

Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories ... can make works fully available online. This helps enable both access to and preservation of cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history.

— Jennifer Jenkins, Duke University, on the value of the public domain

There are also Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon,” originally published as a serial in Black Mask magazine, and John Steinbeck’s first novel, “Cup of Gold.”

Among films, the haul includes the Marx Brothers’ first movie, “The Cocoanuts,” which was based on a George S. Kaufman Broadway musical and betrays its stagebound genesis in almost every scene; Alfred Hitchcock’s first sound film, “Blackmail,” and an early film adaptation of Edna Ferber’s “Show Boat” — a 1929 version of Ferber’s novel, not the musical version, which was filmed in 1936 and, more familiarly, in 1951.

Interpretations of copyright law haven’t been as divergent as they’ve become over the last year or two. The reason is AI, or at least the development of AI bots “trained” on copyrighted written, musical and artistic works. Numerous lawsuits brought by creators are making their way through the federal courts.

AI developers generally claim that their feeding copyrighted works into their bots’ databases falls within the “fair use” exception to copyright protection. The fair use doctrine, as the U.S. Copyright Office puts is, allows the use of “limited portions of a work including quotes, for purposes such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, and scholarly reports.”

Whether a particular use qualifies “is notoriously fact-specific,” Jenkins told me. “So it’s hard to shoot a straight arrow through all the cases,” in part because the judgment of whether a use is exempt from copyright depends on whether creators can show that the use caused harm to the market for their works.

“It’s a wild patchwork of cases,” Jenkins says, “but the central issue to all is the same, namely is it fair use to train your AI model on copyrighted content, but the specifics vary. Often I have something resembling a prediction of how fair use cases are going to come out, but really cannot predict which way these cases are going to go. It’s a moving target in copyright land.”

AI investors say their work is so important that they should be able to trample copyright law on their pathway to riches. Here’s why you shouldn’t believe them.

This isn’t the first time that technological change has roiled the copyright landscape. One precedent is the Google Books case, in which authors and publishers sued Google to block its effort to create a searchable database of written works by digitizing copyrighted works along with works in the public domain.

The ultimate settlement allows Google to digitize books for the database, but to display only limited “snippets” of copyright-protected works to users — enough to enable users to search for specific words or phrases, but not to access significant portions of the works.

Also entering the public domain this week, as Jenkins observes, are about a dozen Mickey Mouse films, including one in which he speaks his first words (“Hot dogs! Hot dogs!”) and wears his iconic white gloves. That depiction of Mickey is now copyright-free; the ur-Mickey depicted in the Walt Disney short “Steamboat Willie” entered the public domain on Jan. 1, 2024, but later depictions such as the white gloves were still subject to copyright restrictions based on when they first appeared on film.

Popeye first appeared as a peripheral character in January 1929 in E.C. Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” comic strip. He garnered such instant popularity that Segar eventually refashioned the strip around him. Some story elements, such as the role of spinach as a source of his superhuman strength, became part of his persona over subsequent years.

Popeye also gives us a window into how a character’s entry into the public domain doesn’t require subsequent exploitations to adhere to his or her original conception.

Los Angeles copyright attorney Aaron Moss observes in his own curtain-raising post about public domain day 2025 that several Popeye-inspired horror films, “including ‘Popeye the Slayer Man,’ set in an abandoned spinach cannery, and ‘Shiver Me Timbers,’ featuring a meteor that ‘transforms Popeye into an unstoppable killing machine,’” have already been announced.

Works by D.H. Lawrence, Evelyn Waugh and Walt Disney are finally losing their copyright protection after nearly a century, underscoring why our copyright rules are absurd

Similarly, er, disrespectful treatments of Mickey Mouse and Winnie-the-Pooh (a member of the public domain class of 2022) have been produced or announced.

The copyright rules for music are particularly convoluted. “Fats” Waller songs including “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue” are entering the public domain, which should help to augment Waller’s reputation as a jazz and Broadway innovator. So too are George Gershwin’s “An American in Paris” and the popular standards “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” (lyrics by Alfred Dubin, music by Joseph Burke), “Happy Days Are Here Again” (lyrics by Jack Yellen, music by Milton Ager) and “What Is This Thing Called Love?” by Cole Porter.

But as Jenkins notes, only the compositions — what appears on the sheet music — and not any particular recordings are entering the public domain. So the version of “Tiptoe” recorded by Tiny Tim, which made that artist a popular star in 1968, is still under copyright.

“Singin’ in the Rain,” which most people associate with the 1952 film musical of that name, is entering the public domain.

Fans of the Gene Kelly/Debbie Reynolds film may be unaware that it was conceived by Arthur Freed, then the head of MGM’s musical feature unit, as a vehicle to exploit the back catalog of songs he and composer Nacio Herb Brown had written in the 1920s and 1930s; of the 16 full-length and excerpted songs in the movie, all but two were original products of their collaboration or had words by Freed or music by Brown. “Moses Supposes” was written by others for the movie and “Make ‘Em Laugh,” by Freed and Brown, was acknowledged by Stanley Donen, who co-directed the firm with Kelly, to be a transparent rip-off of Cole Porter’s “Be a Clown.”

(My favorite backstage nugget about the movie’s production involves the physical torment that Reynolds, not a trained dancer, suffered at the hands of the perfectionist Kelly, which left her with bloodied feet after filming the “Good Morning” number. A close scrutiny of the scene reveals Reynolds continually glancing at the ground to make sure she was hitting her marks as she tried to keep in step with Kelly and co-star Donald O’Connor; anyway, no one can claim it doesn’t work perfectly.)

The cherished works from 1927 losing their copyright protection include the film ‘Metropolis,’ a classic Laurel and Hardy short and the first Hardy Boys book.

Sound recordings from 1924 are entering the public domain thanks to the 2018 Music Modernization Act. They include Gershwin’s recording of “Rhapsody in Blue” and Al Jolson’s recording of “California Here I Come.” But regular sound recordings made in 1929 are granted 100-year copyrights, so they won’t be available until 2030.

Another exception covers music made to accompany movies, which receive the same copyright terms as the films. Accordingly, Jenkins notes, the recorded version of “Singin’ in the Rain” heard in the film “The Hollywood Revue of 1929” goes royalty-free on Jan.1, but not the version sung by Kelly in the 1952 movie.

The annual flow of copyrighted works into the public domain underscores how the progressive lengthening of copyright protection is counter to the public interest—indeed, to the interests of creative artists. The initial U.S. copyright act, passed in 1790, provided for a term of 28 years including a 14-year renewal. In 1909, that was extended to 56 years including a 28-year renewal.

In 1976, the term was changed to the creator’s life plus 50 years. In 1998, Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, which is known as the Sonny Bono Act after its chief promoter on Capitol Hill. That law extended the basic term to life plus 70 years; works for hire (in which a third party owns the rights to a creative work), pseudonymous and anonymous works were protected for 95 years from first publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter.

Along the way, Congress extended copyright protection from written works to movies, recordings, performances and ultimately to almost all works, both published and unpublished.

Once a work enters the public domain, Jenkins observes, “community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories such as the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, Google Books and the New York Public Library can make works fully available online. This helps enable both access to and preservation of cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history.”

Indeed, as Jenkins and others have documented, overly long copyright terms often keep older works out of the mainstream. “Films have disintegrated because preservationists can’t digitize them,” Jenkins has written. “The works of historians and journalists are incomplete. Artists find their cultural heritage off-limits.”

The countervailing benefits are minimal. The artistic lobby — specifically corporate owners of copyrighted content — maintain that longer terms protect the income streams of content creators, producing an incentive to create. But the truth is that after the first few years of publication the commercial value of the vast majority of copyrighted works declines precipitously to almost nothing. The value that might arise from follow-on creations of public domain works remains locked away and the copyrighted works become forgotten.