Column: Uber, Lyft and DoorDash will spend $90 million to avoid paying their drivers better

Uber, Lyft and DoorDash believe in putting their money where their mouth is.

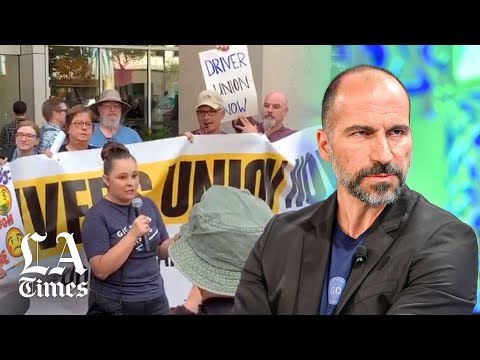

For months, they and other gig economy companies have been trying to talk the California Legislature out of passing a bill that would strengthen employment protections for their drivers. Now, with the bill on the verge of final passage and a solid endorsement from Gov. Gavin Newsom on Labor Day, the time for talk seems to have passed.

Accordingly, the three companies have contributed a combined $90 million — or $30 million each — to back a ballot initiative that would protect them from having to classify their drivers as employees.

We are not arguing for the status quo, nor are we denying that independent work needs to be improved.

— Uber

Let’s put that in perspective. A $90-million war chest would make the firms’ initiative campaign one of the most expensive in California history, just behind the $105 million spent last year, almost all of it by dialysis companies, to beat a ballot measure — Proposition 8 —that would have placed limits on how much the companies could charge for their services. Supporters of the measure mustered only about $20 million.

That reflects a rule of thumb about ballot-box spending: The big money is virtually never aligned with the interests of ordinary voters.

It was clear almost from the first that the California Supreme Court, in a ruling in April 2018, threw the business models of Uber and Lyft companies for a loop.

A corollary is that spending of this magnitude is always a bargain for the donors, who stand to gain a lot more from defeating a ballot measure against their interests (or passing one that enriches them) than they have to spend. Uber, for example, collected $15.7 billion in revenue and Lyft $867.3 million in the quarter that ended June 30.

Both companies are losing money — $5.2 billion and $644 million, respectively, in the latest quarter — but their losses certainly would have been higher if they had had to cover their drivers’ fuel, maintenance and other expenses as well as workers’ compensation and other taxes for them. So their commitment of $30 million each to a ballot initiative campaign would come to a minuscule portion of their annual revenues and might yield narrower losses in the future. (DoorDash, a private company, hasn’t publicly disclosed its financial results.)

The companies haven’t released a draft of their possible ballot initiative. But Uber last week released a “framework” for its proposal, which it’s also pushing via talks in Sacramento over a follow-on bill to AB 5, the measure that Newsom endorsed. The framework echoes principles set forth by the top executives of Uber and Lyft in an op-ed in June.

Uber says its goal is to place “drivers’ unique needs first and foremost, and provide leadership with a new model for workers.” Is this plausible?

Just consider that the top named officer of the campaign entity to which Uber and Lyft have given their $60 million in funding, Californians for Innovation and Opportunity, is Thomas W. Hiltachk. He’s the go-to lawyer for Republican and conservative initiative campaigns, including Proposition 32 of 2012, which was a thinly disguised attack on unions and their members. Here’s a rule of thumb: If Hiltachk is on your team, you may not have workers’ best interests at heart.

Let’s examine the background to this high-stakes and high-priced battle.

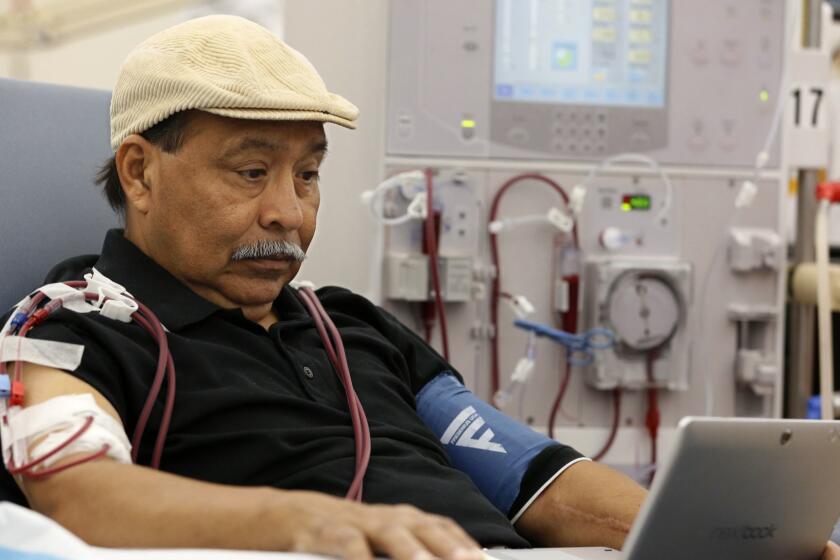

As we reported in July, the foundation of all the political discussion in Sacramento is the so-called Dynamex decision, handed down last year by the state Supreme Court. The case is named after Dynamex International, a package and document delivery company that in 2004 abruptly reclassified all its drivers as independent contractors, not employees. From then on, the drivers were required to provide their own vehicles and pay for all their own expenses, such as fuel, tolls, wear and tear on their vehicles and insurance, including workers’ compensation insurance. They no longer received overtime pay.

The court decision provided employers with a guide to the difference between employees and independent contractors. It established the “ABC test” designating workers as employees unless they’re (A) independent of the hiring entity’s control and direction about how they perform their work; (B) engaged in work different from the hiring entity’s business; and (C) conducting an independent business in the same field as the work they’re doing for the hiring entity.

In other words, a plumber hired by a clothing store to fix a leaky bathroom faucet is an independent contractor. A driver picking up passengers for Uber is an employee.

AB 5 would apply the ABC test to a wide range of workplaces and to unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation coverage, in addition to wage and hour rules. It wouldn’t guarantee drivers the right of collective bargaining, which falls under federal law.

As my colleagues Margot Roosevelt, Liam Dillon and Johana Bhuiyan have reported, the gig economy companies argue that their ostensibly novel employment model should be exempted from AB 5 because they offer workers the ability to set their own schedules and work for multiple companies. AB 5 could cost the firms millions of dollars.

Big companies don’t normally invest tens of millions of dollars with the expectation of losing.

Uber’s framework encompasses what it says would be pay for drivers above the minimum wage “for every hour they have a rider in the car, or are driving to pick one up,” and “compensation for average expenses.” The companies also propose what they call “access to benefits” such as sick leave and some form of coverage for an injury stemming from an accident while driving. They propose “sectoral bargaining,” which they describe as “a legally protected right to negotiate over earnings, benefits and other decisions that impact their livelihood.”

“We are not arguing for the status quo, nor are we denying that independent work needs to be improved,” Uber said in releasing its framework.

Much of this framework is a chimera, however.

Lyft and Uber drivers say they spend as much as 60% of their time waiting for a driving gig, which is excluded from the framework’s calculation of time spent picking up or driving with a passenger. The distinction might even encourage the companies to add more drivers to their independent fleets, competing with one another for passengers. “It costs them nothing to have thousands of drivers on the street,” observes Nicole Moore, a Lyft and Uber driver and an organizer of Rideshare Drivers United, an independent drivers group.

“Sectoral bargaining,” which Uber describes as “a type of collective bargaining,” is anything but. It functions only in situations in which no union exists, thus depriving workers of a truly consistent voice and organized power. True collective bargaining via union representation, under federal law, is available only to employees, not independent contractors. And the promise of “access to benefits” is vague as long as it lacks standards for employer contributions to the cost or descriptions of the benefits.

In short, Uber, Lyft and DoorDash — and any other gig companies that choose to sign on to their campaign — are merely trying to circumvent the employment rights embodied in the Dynamex ruling and AB 5. The best way to improve independent work, which Uber says is its goal, is to guarantee all the rights and benefits that come with employment.

The companies acknowledged in their op-ed that “a change to the employment classification of ride-share drivers would pose a risk to our businesses.” The commitment of $90 million to averting that change is only a hint of how much it really would cost them.