‘Everything is already decided’: Thailand’s army is set to cement power with an election

- Share via

Reporting from Bangkok, Thailand — Wearing identical white nylon track jackets, seemingly impervious to the swampy afternoon heat, the half-dozen candidates breezed through a sprawling covered market on the outskirts of Bangkok and waved to a smattering of shoppers.

Days before Thailand’s first national elections in eight years, party workers raced ahead to distribute long-stemmed roses to shopkeepers. The merchants then politely handed the flowers to the candidates — members of Palang Pracharat, a brand-new party representing Thailand’s ruling military junta — with brief bows and smiles for the accompanying cameras.

Casting a sideways glance from behind bagfuls of onions and green chiles, shopkeeper Harit Wichachai was unimpressed.

“It seems they have the election in their pocket,” Harit, a 29-year-old from rural northern Thailand, said of the pro-military party. “Everything is already decided.”

Since seizing power in a 2014 coup, the army has repeatedly pledged to restore democracy. But many Thais see the vote, being held Sunday after numerous delays, as likely to extend military rule.

With curbs on free speech, legal moves against opposition groups and new election rules that weaken major parties — while reserving one-third of parliamentary seats for military appointees — experts say the army has virtually guaranteed that it will hold on to power despite minimal enthusiasm for its repressive policies and lackluster economic growth.

How the CIA’s legacy of torture lives on in Thailand, home of the agency’s original ‘black site’ »

Former Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha, the junta leader who has been serving as prime minister since being appointed by a handpicked legislature, is bidding to remain in office as the candidate of Palang Pracharat, formed four months ago to serve as the military’s political vehicle.

The party’s public events and rallies have drawn middling crowds. But even if anti-junta parties scrape together a majority in the 750-seat legislature, some analysts say that a judiciary and election commission loyal to the army could block the formation of a civilian-led government or appointment of a new prime minister.

“This election will be utterly unfair — and free only up to a point — in view of the junta’s likely manipulation and coercion to get outcomes it wants,” said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a political science professor at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University.

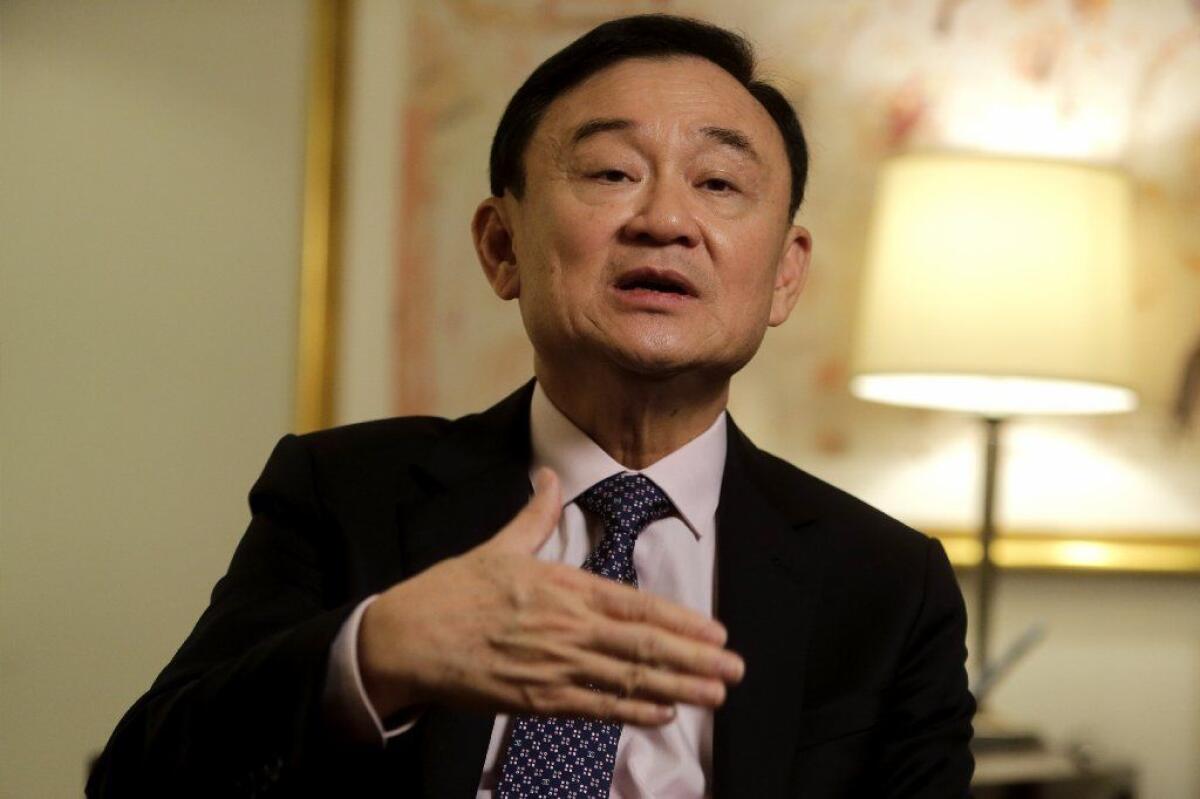

The balloting marks the culmination of a more than decade-long, military-backed project to prevent the return of one man: Thaksin Shinawatra, an exiled former prime minister and telecommunications tycoon who is Thailand’s most polarizing political figure.

Pro-Thaksin parties have won every national election in this Southeast Asian kingdom since 2001. But his populist policies, self-aggrandizing style and efforts to exert authority over the security services made him a bogeyman for Thailand’s conservative establishment, which saw his rise as a threat to the monarchy.

After massive street protests, Thaksin was ousted in a 2006 coup and his party dissolved by the courts. His sister Yingluck Shinawatra won election at the helm of a new party, only to be driven from office in 2014.

For many Thais, a way out of the cycle of military takeovers and popular unrest appeared, as if from above, in February. A widely admired former princess, Ubolratana Mahidol, the eldest child of Thailand’s late king and sister to its current monarch, announced one morning that she was running for prime minister as a member of Thai Raksa Chart, one of several parties formed as proxies of Thaksin.

The possibility was tantalizing. In Thailand, where the monarchy is revered as nearly godlike, a rapprochement between the royal family and the country’s most popular politician could have united 70 million Thais ahead of the king’s coronation in May.

Officially, the royal family floats above politics, but in practice the monarchy has often pulled strings behind the scenes. With army supporters livid that a royal would join forces with the hated Thaksin, Ubolratana’s brother, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, issued an extraordinary late-night decree that deemed her candidacy “extremely inappropriate.”

This month, a court banned the party and disqualified its candidates, dealing a significant blow to the pro-Thaksin grouping’s already slim chances of assembling a parliamentary majority.

“For about 24 hours, it was one of the single most politically significant moves in modern Thai history,” said Benjamin Zawacki, a Bangkok-based analyst and author. “It looked like a brilliant move by Thaksin — an X-factor that would have shifted the landscape. I saw her as unbeatable.

“And then it was over, and what had been inevitable became even more inevitable.”

The military government has banned foreign election observers, but few expect Thailand to pay a price diplomatically.

The generals have courted investment and arms deals from China, potentially threatening the long security partnership between the U.S. and Thailand.

In Washington, criticism of the junta has been muted: The U.S. cut some military funding after the coup and scaled back an annual joint military exercise known as Cobra Gold — but only temporarily.

The junta’s supporters say it has ended the paralyzing, sometimes deadly street protests that drew pro- and anti-Thaksin camps, and sometimes army tanks, into the streets, scarring the country’s image as a tourist-friendly “Land of Smiles.”

At a party office in Sai Mai, a working-class Bangkok suburb, Wilaiwan Ponsawat, the 38-year-old owner of a dress shop, said she was participating in politics for the first time to volunteer for Palang Pracharat.

“The country is peaceful,” she said. “When we had protests in the middle of Bangkok in 2010, I had to close my shop for one month. Now my business is booming.”

Addressing supporters, party leader Uttama Savanayana, a former minister in the military government, said that only Prayuth could ensure Thailand’s stability.

“How many people can you think of who can lead the country to peace?” he said. “If he doesn’t win, I can assure you, there will be a lot of conflicts.”

Panitan Wattanayagorn, a political scientist and advisor to the deputy prime minister in the military government, said the new electoral rules — which allow greater representation for smaller parties in the 500-seat House of Representatives — were designed to move Thailand out of a long crisis between two dueling political factions.

“It’s not a Western, liberal democracy, but it represents a halfway approach,” he said. “A simple majority electoral system failed Thailand in the last two decades.”

Still, enthusiasm for the election remains high, and some forecasters project that more than 80% of Thailand’s 51 million eligible voters will cast ballots.

About 7 million Thais will be able to vote for the first time. The young demographic has fueled the rise of an upstart anti-junta party called Future Forward, led by a 40-year-old businessman-turned-politician, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, who has captivated fans with his down-to-earth style, fervent opposition to military rule and made-for-TV looks.

The judiciary has gone after Thanathorn: He faces criminal charges related to a Facebook Live post last year in which he criticized the junta’s use of the Palang Pracharat party to retain power. Other opposition politicians have been hit with sedition and computer crimes charges for speaking or writing online posts against military rule.

The legal cases and the dissolution of the former princess’ party might actually have galvanized anti-military voters, said Tyrell Haberkorn, a Thailand expert at the University of Wisconsin.

“My sense is this has made even people who were uninterested in politics before become interested,” she said. “I think that the growth and the excitement about Future Forward that has happened in the last few months is remarkable.”

Narumol Phoket, a 37-year-old co-owner of a street-side Bangkok cafe who supports Thaksin, said she lost hope and briefly considered not voting after the former princess was barred from running.

“But then I thought more about it,” she said. “We have waited a long time for this election. At the end of the day, I have to exercise my rights.”