Paris strikes and their aftermath expose security lapses in Europe

Reporting from Paris — For centuries, the cathedral town of St.-Denis north of Paris has been known for its majestic Gothic basilica housing the tombs of French royalty, from Dagobert, King of the Franks, to Marie Antoinette, the guillotine’s most celebrated victim.

In recent days, however, the now-gritty Paris suburb, home to a large immigrant population, many of them Muslims, won new global renown because of a very contemporary figure: Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the suspected architect of the Nov. 13 string of attacks on Paris restaurants, bars, a concert hall and a soccer stadium, that left at least 130 dead.

French intelligence analysts had apparently believed that Abaaoud, previously linked to several plots in Europe, had helped orchestrate the Paris attacks from a secure perch back in Syria. But it turned out that he and several accomplices were holed up in a third-floor flat on the Rue du Corbillon, just off St.-Denis’ cobblestoned main drag, a 20-minute walk to one of the attack sites, the Stade de France national stadium.

Abaaoud, 28, a Belgian national of Moroccan origins, is among the most notorious of the thousands of radicalized Europeans who have ventured to Syria to wage jihad. But he was practically hiding in plain sight.

Abaaoud and two others died in a hail of gunfire Wednesday when police raided the St.-Denis flat after authorities belatedly discovered that the terrorist operative was probably closeted there, not on the battlefields of Syria. The ability of Abaaoud, a wanted terrorist with a lengthy rap sheet, to travel back into France without setting off alarms is just one of a number of security lapses that the Paris strikes have exposed.

“It’s not about the flaws of one country or another, but a collective collapse,” said Jean-Charles Brisard, head of the French Center for Analysis of Terrorism, a think tank. “France and Belgium both failed in identifying people. There is no one country guiltier than the other.”

The security shortcomings have triggered much soul-searching in Europe, which is proving especially vulnerable to the turmoil radiating from the mayhem in Syria.

On Friday, ministers of France, Belgium and nations across Europe met in Brussels and vowed to do more to seal the continent’s porous frontiers from terrorist infiltrators. Officials pledged tougher border controls, improved information exchange among nations and stiffer laws to stem the flow of arms.

It was a crisis-driven response to a threat not likely to end any time soon, as any of the more of the 3,000 European residents off to fight jihad in Syria could filter back into Europe intent on wreaking havoc. Their passports, language skills and ability to meld into European society make them especially valued terrorist operatives, experts say.

“Criminals and terrorists use frontiers against us,” said Nils Duquet, a researcher at the Flemish Peace Institute, a parliamentary body, who specializes in the arms trade. “When confronted with a transnational problem like terrorism, we need a European answer.”

Despite concern expressed about civil liberties, French lawmakers in the last week extended a state of emergency for three months, giving police sweeping new authority to arrest suspects, carry out searches, bar people’s movements and even shut down websites.

“This is the fast response of a democracy faced with barbarism,” Prime Minister Manuel Valls told the French Parliament last week.

In Washington, U.S. law enforcement officials have long been wary of France’s relatively open borders and security lapses, which could allow terrorist cells to move seamlessly between nations. Further aggravating the situation, they said, is that European countries, like most nations around the world, do not always readily share crucial intelligence information.

“Everyone has a lot of work to do in working together, and there’s always going to be blips,” one Homeland Security official said Saturday, speaking confidentially because of the delicacy of the situation.

The Paris assailants appeared to be mostly, if not all, French or Belgian nationals, with close links to extremists in Syria.

Abaaoud drew from a network of friends and associates on his home turf in the working-class Brussels borough of Molenbeek St. Jean.

Like Abaaoud, at least three of the suspected attackers had traveled to Syria to join militant groups and apparently managed to return to Europe without raising intelligence alerts. And, like Abaaoud, they probably used the cover of the massive migrant flow from Syria to reenter Europe, authorities said.

Several of the Paris attackers had been under previous police scrutiny but were not considered imminent threats or had dropped out of sight, according to reports here.

Similarly, in the Charlie Hebdo attacks here that left 17 dead in January, all three assailants were native-born Frenchmen who had fallen off the law enforcement radar screen despite past links to Islamic extremists.

Experts say the sheer number of potential extremist operatives and battle-hardened returnees from Syria means that resource-challenged European authorities must focus on those deemed most threatening.

Full-time surveillance of any one suspect — or even monitoring all of a person’s phone calls — requires a substantial law enforcement commitment. Inevitably, some individuals may fall through the cracks.

In the case of the Paris attacks, one suspect who remains a fugitive, Salah Abdeslam, seems to have literally slipped through police hands.

Abdeslam, a friend of Abaaoud from their days together in Molenbeek St. Jean, was in a car stopped by French police on the morning after the attacks near the Belgian border, but he was allowed to proceed. At the time, Abdeslam had not yet surfaced as a possible participant.

Later, authorities learned that his brother, Brahim, had blown himself up as part of the Paris operation, authorities said. Five other attackers also set off suicide bombs and one was shot dead by police, authorities said.

Salah Abdeslam remains the subject of a massive manhunt.

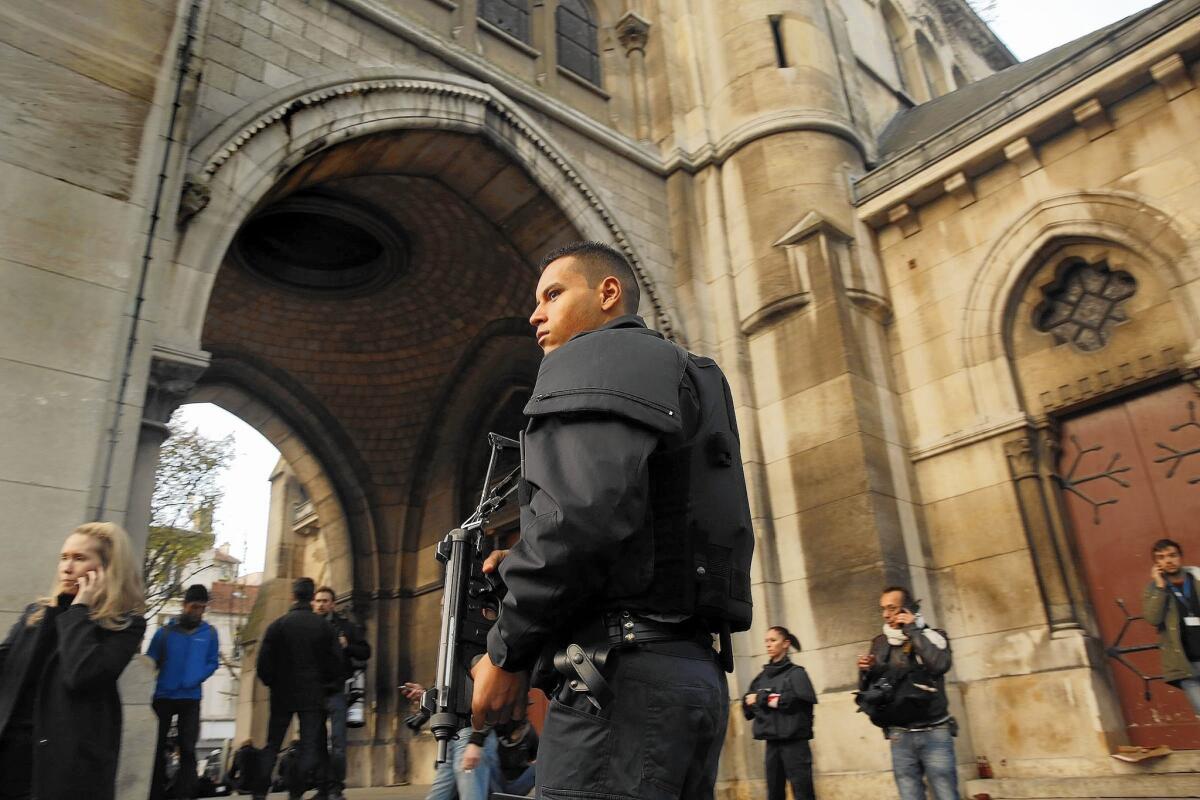

In St.-Denis on Saturday, forensic investigators wearing white protective gear and masks were still sifting through the charred ruins of Abaaoud’s former safe house, which was destroyed in a predawn police onslaught in which officers fired more than 5,000 rounds.

A few blocks away, the medieval cathedral and its extraordinary royal necropolis opened for visitors after shutting down for two days. But staffers seemed jittery.

At City Hall, facing the Place Victor Hugo, a huge banner urged solidarity as a shaken capital struggles with a calamity that has left anxiety and wariness.

“The best response to barbarism,” the banner advises, “is to confront it directly [and] together.”

Special correspondent Clara Wright in Paris and Times staff writer Richard Serrano in Washington contributed to this report

ALSO

Five Syrian asylum seekers surrender at Texas border crossing

Belgium raises threat alert to highest level after Paris attacks

At refugee center in Malaysia, Obama calls on U.S. to welcome the ‘forgotten’