More than 200,000 people wait in limbo as the Philippines fights Islamic State’s allies in Mindanao

- Share via

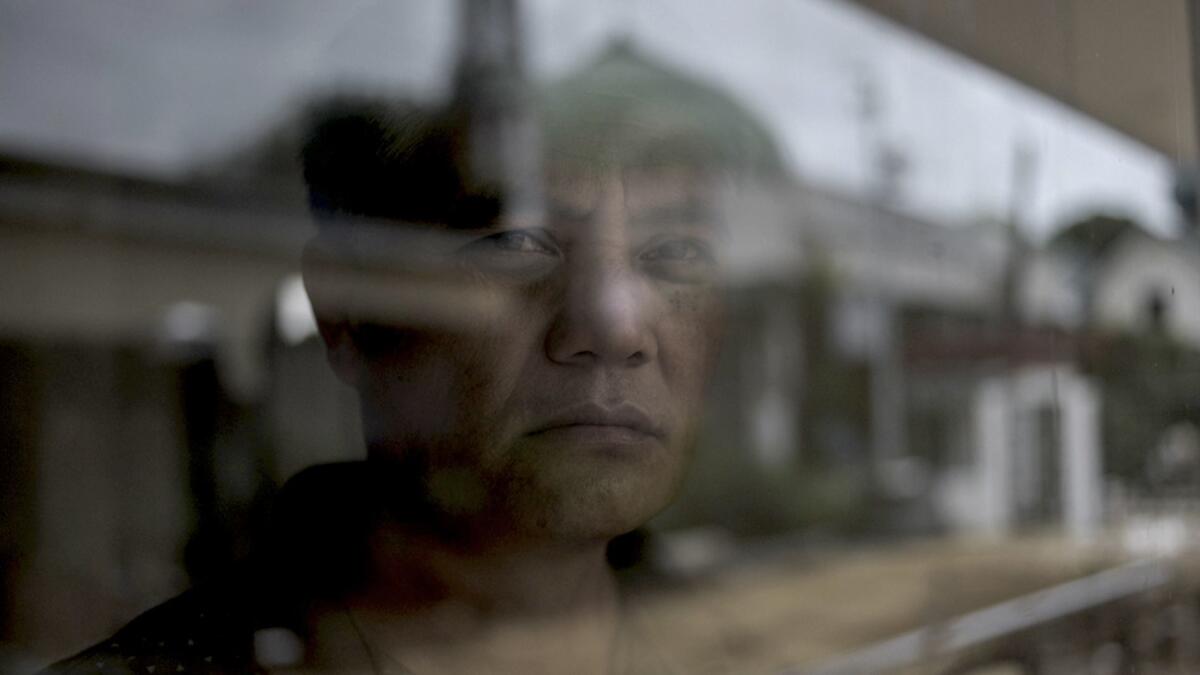

Reporting from Marawi City, Philippines — In an evacuation center filled with parents running after scampering children and adults huddled together on mats, Saipoding Mariga stood alone.

He spent his days wandering aimlessly, trying to pass time while waiting for word about his wife, Geraldine. She was trapped in their home in the city of Marawi, in the southern Philippines, which rebels affiliated with Islamic State had seized in late May.

They had torched buildings and raised their black flags, staking their claim to an overwhelmingly Muslim city where alcohol sales were already forbidden and pork, a staple of diets throughout the Philippines, was not openly sold.

Electricity was cut off and the entire city was plunged into darkness.

Geraldine, 36, had managed to move their seven children to safety, but she was wounded and unable to flee. Mariga, who had been away on business in Manila when the fighting broke out, could not reach her on her cellphone and did not know if she was dead or alive.

At one point, the 43-year-old brought bananas and water to the military barricade that separated him from his wife and begged the soldiers to let him through.

“I told them that she would have run out of food by now and must be hungry,” Mariga said, breaking into sobs.

He was among hundreds of anguished family members cut off from loved ones trapped in the conflict zone.

It has been a month since the Maute extremist group seized Marawi, in the province of Lanao del Sur on the Philippine island of Mindanao.

Terrorism experts say that the battle for Marawi could be setting the stage for the establishment of a jihadist state in Southeast Asia as Islamic State strongholds in Syria and Iraq begin to fall.

“It’s the first real battle of a war that will rage much longer …. It has demonstrated that Lanao del Sur is the epicenter of IS in the Philippines,” said Justin Richmond, executive director of Impl.project, a nongovernmental organization working to counter violent extremism in Mindanao.

Caught in the crossfire

More than 200,000 residents fled when Marawi became a war zone, leaving just an estimated 300-500 civilians trapped or held hostage in the city center. Most who fled stayed with relatives, but an estimated 40,000 are squeezed into gyms, Islamic schools and government offices converted to evacuation centers.

Health officials have recorded at least 24 deaths from dehydration, pneumonia and other illnesses in the centers and many more are getting sick.

Overall, more than 300 deaths have been confirmed in the conflict and many more are feared. Rescuers and survivors reported running past corpses in the conflict zone being fed upon by dogs and pecked at by chickens.

The Philippine armed forces, who have been fighting a long-standing insurgency in the hinterlands and jungles, are struggling with the unfamiliar terrain of urban warfare and the strategic positions taken by the rebels.

Despite deep strains with Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, the U.S. military — with vast recent experience in urban warfare — has been quietly providing assistance. On June 14, Philippine military spokesman Brig. Gen. Restituto Padilla said that American troops were in Marawi, although not engaged in combat.

Military spokesman Jo-Ar Herrera said rebels had burrowed themselves into foxholes and stationed sniper nests in tall buildings, and were using mosques and schools to store their weapons.

“They are also using hostages as human shields,” said Herrera. He added that, based on information from those who managed to escape, the Maute were forcing them to cook food, carry their weapons and retrieve their dead.

The Philippine military has taken to the sky, conducting aerial strikes at least twice a day and raising concerns about civilian casualties.

Last week, Duterte said he would order “carpet bombing” of Marawi if needed to end the rebellion.

“You don’t invade it with men. You really crush it with bombs,” he said. “If I have to flatten the place, I will do it.”

“Our hands are tied,” said Zia Alonto Adiong, spokesman for the Joint Task Force Marawi Provincial Crisis Committee.

With rescue efforts becoming more dangerous, many trapped civilians have dared to cross an exposed bridge to get to a checkpoint manned by government troops. Some have made it past the sniper fire that rained on them from rebels; others have not.

Underestimating the enemy

The fighting began May 23, when the military raided a Marawi village where Insilon Hapilon, leader of the Abu Sayyaf kidnap-for-ransom group, was reported to be hiding. The military planned for a swift and precise “surgical operation” to extract the militant leader, but was caught off guard when armed men took to the streets, putting up fierce resistance.

This is not the first time that southern Mindanao has been beset by militancy and insurgency, but the Marawi siege is the first indication of an alliance between the Maute group and the notoriously brutal Abu Sayyaf.

The Maute claimed responsibility for a September 2016 bombing in Davao City (also in the southern Philippines) and, later, attempted to take over Butig, a town 32 miles south of Marawi.

The group was started by two brothers, Omarkhayam and Abdullah Maute, members of a prominent family in Butig. They are believed to have been radicalized when they were studying in Egypt and Jordan.

The government dismissed the Maute as mere bandits — annoying but not especially dangerous. Residents, accustomed to clan wars, were sure everything would be over in a few days. Duterte quickly proclaimed martial law on all of Mindanao.

But the military would later concede that it had underestimated the size and capability of the Maute group.

“The military had intelligence on the group,” said Herrera, the military spokesman. “What we didn’t expect was their [fighters] might be backed by criminal and armed group elements, including the presence of foreign fighters,”

Stories of survival

Mariga’s wait ended June 13, when the military rescued Geraldine. Her wounds were becoming infected and she was slipping into septic shock, but she was alive. Doctors operated and later reported that she was stable.

Others caught in the crossfire have not been as lucky.

The Bureau of Fire Protection, working together with local rescue teams, said that those who survived told stories of folding themselves into corners, away from windows and sniper bullets.

“They would hide in one room where they slept, urinated, defecated and ate — when they still had food,” said Fire Protection Officer Queng Lara.

One group shredded a cardboard box and chewed on it as food. Others drank rainwater to keep hydrated.

“But all of them were in a state of shock and trauma,” said Lara.

Fire officials anticipate that, as the conflict enters its second month, it is mostly the elderly, the disabled or the wounded who are still trapped.

“We can only hope for the best,” Lara said.

Santos is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Naval commander stresses no change in U.S. policy on South China Sea

UPDATES:

5:25 p.m.: The story was updated with a comment from the Philippine president.

This story was originally published at 1:25 p.m.