Putin extends rule in preordained Russian election after harshest crackdown since Soviet era

President Vladimir Putin extended his reign over Russia in a landslide election whose outcome was never in doubt, declaring Monday his determination to advance deeper into Ukraine and dangling new threats against the West.

After the harshest crackdown on dissent since Soviet times, it was clear from the earliest returns that Putin’s nearly quarter-century rule would continue with a fifth term that grants him six more years. Still, Russians heeded a call to protest Putin’s repression and his war in Ukraine by showing up at polling stations at noon Sunday.

With all the precincts counted Monday, election officials said Putin had secured a record number of votes, underlining the Russian leader’s total control of the country’s political system. Western leaders denounced the election as a sham.

Putin has led Russia as president or prime minister since December 1999, a tenure marked by international military aggression and an increasing intolerance for dissent. At the end of his fifth term, Putin would be the longest-serving Russian leader since Catherine the Great, who ruled during the 18th century.

Voters head to the polls in Russia for a three-day presidential election that is all but certain to extend Vladimir Putin’s rule by six more years.

Emboldened by his sweeping victory, Putin said he planned to carve out a buffer zone in Ukraine to protect Russia from cross-border shelling and attacks. Asked if an open clash could erupt between Russia and NATO, Putin responded curtly by saying: “Everything is possible in today’s world,” adding: “it’s clear to everyone that it will put us a step away from full-scale World War III.”

Russian officials said they recruited more than 500,000 volunteers for the army last year, but many expect Putin to mobilize more forces to attempt to push deeper into Ukraine.

Putin hailed early results showing him with a firm lead as an indication of “trust” and “hope” in him — while critics saw them as another reflection of the preordained nature of the election.

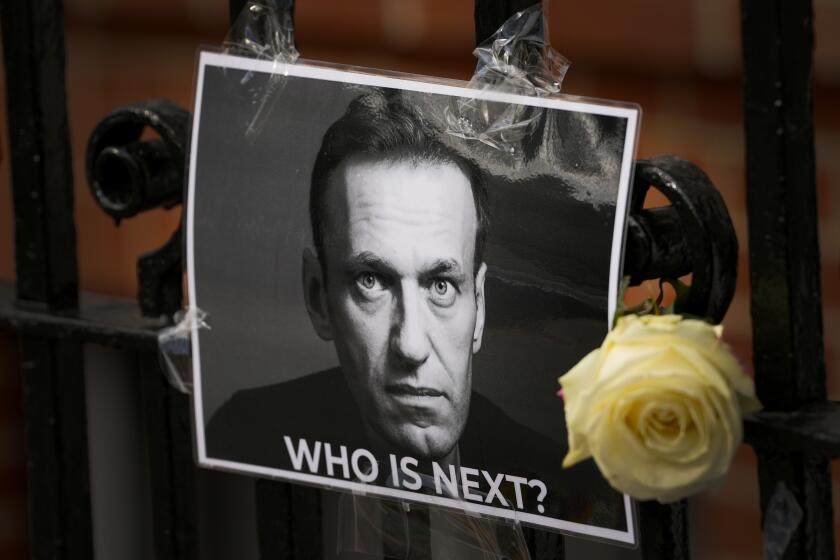

Any public criticism of Putin or his war in Ukraine has been stifled. Independent media have been crippled. His fiercest political foe, Alexei Navalny, died in an Arctic prison last month, and other critics are either in jail or in exile.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has gone from tolerating dissent to suppressing any challenger. Most Russian opposition politicians are in prison or exile.

Voters had no real alternatives to Putin, and independent monitoring of the election was extremely limited.

Russia’s Central Election Commission said Monday that with all the precincts counted, Putin got 87% of the vote. Central Election Commission chief Ella Pamfilova said that nearly 76 million voters cast their ballots for Putin.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was particularly critical of the election and voting in regions of his country that Russia has illegally annexed, saying “everything Russia does on the occupied territory of Ukraine is a crime.”

Germany sharply criticized the vote with Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s spokeswoman, Christina Hoffmann, saying that “in our opinion, it was not a democratic election.”

“Russia, as the chancellor has already said, is now a dictatorship and is ruled by Vladimir Putin in an authoritarian manner,” she told reporters in Berlin.

Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis also derided the voting in Russia: “some might call it reappointment, lacking any legitimacy.”

The Russian opposition lost its brightest star when politician Alexei Navalny died in an Arctic penal colony.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi congratulated Putin, as did North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and the presidents of nations that have historic and current ties to Russia, such as Azerbaijan and Belarus.

Navalny’s associates urged those unhappy with Putin or the war to go to the polls at noon on Sunday — and lines outside a number of polling stations both inside Russia and at its embassies around the world appeared to swell at that time.

Navalny’s widow, Yulia Navalnaya, who spent more than five hours in the line at the Russian Embassy in Berlin, told reporters that she wrote her late husband’s name on her ballot.

Asked whether she had a message for Putin, Navalnaya replied: “Please stop asking for messages from me or from somebody for Mr. Putin. There could be no negotiations and nothing with Mr. Putin, because he’s a killer, he’s a gangster.”

Putin referenced Navalny by name for the first time in years at the news conference, declaring that he had been ready to release him in a swap for unidentified inmates in Western custody just days before the opposition leader’s death.

Supporters of Navalny streamed to his grave in Moscow, some bringing ballots with his name written on them.

When Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny died suddenly last month in an Arctic prison, his team was left with a monumental challenge: sustaining an opposition movement against President Vladimir Putin without the living example of their defiant and charismatic leader

The Russian leader brushed off the effectiveness of the apparent protest and rejected Western criticism of the vote. Instead, he tried to turn the tables on the West, charging that the four criminal cases against former President Trump were a use of the judiciary for political aims.

“The whole world is laughing at it,” he said.

Some people told the AP that they were happy to vote for Putin — unsurprising in a country where state TV airs a drumbeat of praise for the Russian leader and voicing any other opinion is risky.

Dmitry Sergienko, who cast his ballot in Moscow, said, “I am happy with everything and want everything to continue as it is now.”

Voting took place over three days at polling stations across the vast country, in illegally annexed regions of Ukraine and online.

Ukrainian strikes inside Russia have damaged Vladimir Putin’s reassurances to his countrymen that their lives have been largely untouched by the war.

Several people were arrested, including in Moscow and St. Petersburg, after they tried to start fires or set off explosives at polling stations while a few others were detained for throwing green antiseptic or ink into ballot boxes. Many more were rounded up by police for attempting to protest.

The OVD-Info group that monitors political arrests said that about 90 people were arrested in 22 cities across Russia on Sunday.

Stanislav Andreychuk, co-chair of the Golos independent election watchdog, said Russians were searched when entering polling stations, there were attempts to check filled-out ballots before they were cast, and one report said police demanded a ballot box be opened to remove a ballot.

Huge lines formed around noon outside diplomatic missions in London, Berlin, Paris and other cities with large Russian communities, many of whom left home after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

“If we have some option to protest I think it’s important to utilize any opportunity,” said 23-year-old Tatiana, who was voting in the Estonian capital of Tallinn and said she came to take part in the protest.

Burrows, Litvinova and Heintz write for the Associated Press.