Last survivors of Hiroshima bombing watch as Biden pays tribute, but issues no apology

HIROSHIMA, Japan — The patter of rain had subsided on a gray Friday morning as President Biden and other Group of 7 leaders arrived at the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima, the first of two Japanese cities where American planes dropped atomic bombs in August 1945, laying waste to both and leading to the end of World War II.

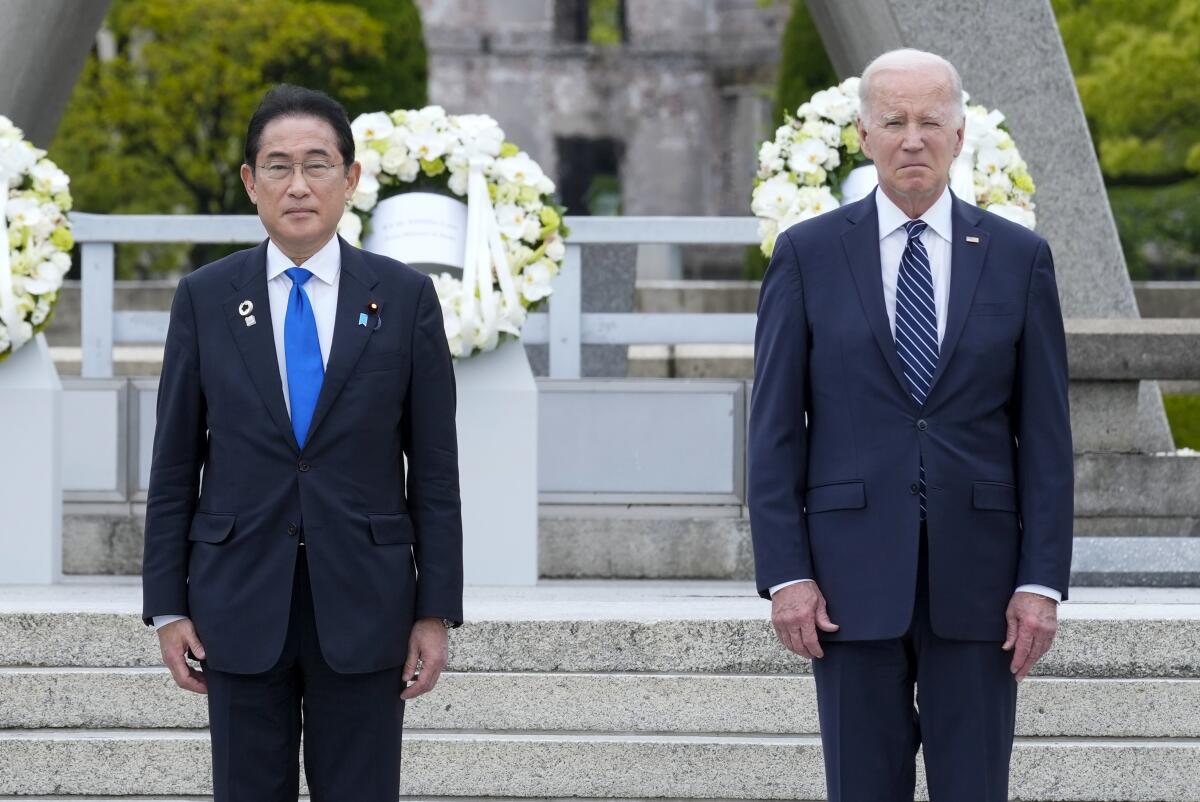

Tanaka Satoshi, a 79-year-old hibakusha, or survivor of the atomic bombings, watched closely on television. Biden, the leader of the country that carried out the world’s only nuclear attacks, stood in front of the Cenotaph, a memorial shaped to resemble a Japanese dwelling. The arched monument is designed to metaphorically shelter the estimated 140,000 people who perished in the Hiroshima blast or died from the resulting fires and radiation.

After Biden and his foreign counterparts placed wreaths of white flowers at the foot of the memorial, Hiroshima Mayor Matsui Kazumi explained the carefully worded inscription: “Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil.”

The leaders listened, staring into the distance at the skeletal ruins of the Atomic Bomb Dome, the only structure that was left standing inside the blast zone that day.

This world’s first atomic bomb attack hit Hiroshima 75 years ago this week. Time is running out for survivors to tell their stories.

Satoshi’s fervent hope was for world leaders to see the message inscribed on the concrete memorial.

“I think we can now say they have made the promise that they will never repeat the same wrongs,” Satoshi told The Times. “And I hope Biden takes this promise with him.”

The ceremony opened the G-7 summit, where leaders of some of the world’s most powerful economies planned to discuss pressing global issues, including the war in Ukraine, climate change and the global economy’s dependence on China. But their visit to Hiroshima was a reminder that the threat of nuclear destruction is closer now than perhaps any time since the Cold War.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has made overt threats to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, abandoning the last major nucleararms control treaty in February. North Korea’s barrage of missile tests recently prompted Biden to reaffirm Washington’s commitment to protect South Korea with nuclear weapons. Iran has continued to pursue nuclear weapons, while China is on track to increase its stock of nuclear warheads to around 1,500 by 2035, according to the Pentagon.

Biden, who vowed to make arms control and nonproliferation “a central pillar of U.S. global leadership” during the 2020 campaign, has moved away from that promise, instead staking his foreign policy on coordinating an international response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and constraining China’s sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

Before the leaders left Peace Memorial Park, news broke of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s plans to join the summit on Sunday as they prepare to announce a new round of sanctions against Russia.

Many of the hibakusha, around 119,000 of whom were still alive as of March 2022, according to a Japanese government estimate, had asked Japanese officials ahead of the summit to push for nuclear disarmament. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, whose family is from Hiroshima, had hoped to do so.

But Putin’s threat of nuclear retaliation has only bolstered U.S. and other G-7 countries’ policy of deterrence, which hinges on a “credible” threat of using nuclear weapons. Only India, a nuclear-armed country that is not a member of the G-7 but is attending this year’s summit, has adopted a “no first use” nuclear doctrine.

Kishida’s quest for a world without nuclear weapons stands in conflict with Japan’s dramatic shift from the pacifist foreign policy it forged in the aftermath of World War II, toward a more militarized national security strategy. The Japanese leader vowed to double Tokyo’s defense budget and acquire long-range missile systems to help confront Beijing’s military buildup in the region. Tokyo is also protected under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, despite Japan’s long-standing calls for other countries to abandon nuclear weapons.

At a White House meeting Friday, President Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida signaled a more confrontational approach to China.

Though Kishida is a “true believer in a world without nuclear weapons,” as prime minister he has had to come to terms with the inherent contradiction between nuclear disarmament and extended deterrence, said Daniel Russel, who served as the top U.S. diplomat for Asia under President Obama.

“He’s caught between the ideal of nuclear disarmament and the sad reality of growing proliferation,” Russel said. “But that’s not going to stop him from pursuing the ideal, and Hiroshima is a really powerful venue.

“You can’t be a human being and go to the Hiroshima Memorial Museum and sort of not be seized with the incredible destructive power of nuclear weapons and the human tragedy that it left in its wake,” he added.

Satoshi had hoped the visit would have a similar impact on Biden and other leaders. He was just 1½ years old when the atom bomb dropped, living in the Yamaguchi prefecture, where his father served in the military. After news of the attack, Satoshi’s mother rushed to Hiroshima to search for her family, who lived about half a mile from the spot beneath where the bomb exploded.

Carrying Satoshi on her back, she climbed over piles of charred debris, smoke still rising from the ashes, and occasionally stepped on corpses as she searched for the ruins of her family’s house. His mother eventually identified the home by a half-destroyed shrine gate and a small lantern. Six of her family members were trapped beneath the collapsed building. Four were dead when she found them and the other two died of their injuries later.

Though he was not in Hiroshima when the bomb dropped, Satoshi is considered one of the “entrant hibakusha,” those who entered the city shortly after the attack. He has survived five different types of cancer that he attributes to radiation exposure. The Japanese government has provided medical support for survivors of the bombings, many of whom endured lifelong injuries and illnesses from the radiation that pervaded the city.

“Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction, but at the same time, they continue to kill people forever,” Satoshi said. “When we allow nuclear weapons to proliferate and we continue like that, I would say that everyone on Earth will one day become a nuclear victim. Nuclear weapons and humans cannot coexist.”

Obama was the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima, in 2016. Kishida, then the Japanese foreign minister, escorted the president on a tour of the Peace Memorial. Obama delivered a rousing speech, but it did not include a U.S. apology for dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki — a decision Biden also made when he silently paid tribute at Friday’s opening event.

Though some in Japan had called for Biden to apologize for America’s use of nuclear weapons, his visit to the Peace Memorial was never intended to be featured as a pivotal moment for the U.S.-Japanese relationship, according to Zachary Cooper, a former National Security Council aide and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Still, Biden’s presence was freighted with symbolism.

“Part of the message that we’re hearing from the Japanese is: We’re not here to look back, but look forward,” Cooper said. “We need to get past history issues and start thinking about the challenges ahead.”

Obama, who addressed the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during his visit to Japan, drafted several versions of his speech, according to Russel, who helped plan the trip. Obama called for nations to “have the courage to escape the logic of fear, and pursue a world without [nuclear weapons.]”

Seven years later, the U.S. and its allies appear no closer to nonproliferation or disarmament.

After visiting the Peace Memorial Park, the G-7 members released a statement condemning Russia’s nuclear rhetoric and undermining of arms control as “dangerous and unacceptable.”

“We reiterate our position that threats by Russia of nuclear weapon use, let alone any use of nuclear weapons by Russia, in the context of its aggression against Ukraine are inadmissible,” the statement read.

The group, however, offered no new ideas or actions to reduce the threat of nuclear war.

Daniel Hogsta, interim executive director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, called the G-7 countries’ statement a “gross failure of global leadership.”

“Simply pointing fingers at Russia, China and North Korea is insufficient,” he added. “We need the G-7 countries, which all either possess, host or endorse the use of nuclear weapons, to step up and engage the other nuclear powers in disarmament talks if we are to reach their professed goal of a world without nuclear weapons.”