California will remake San Quentin prison, emphasizing rehab

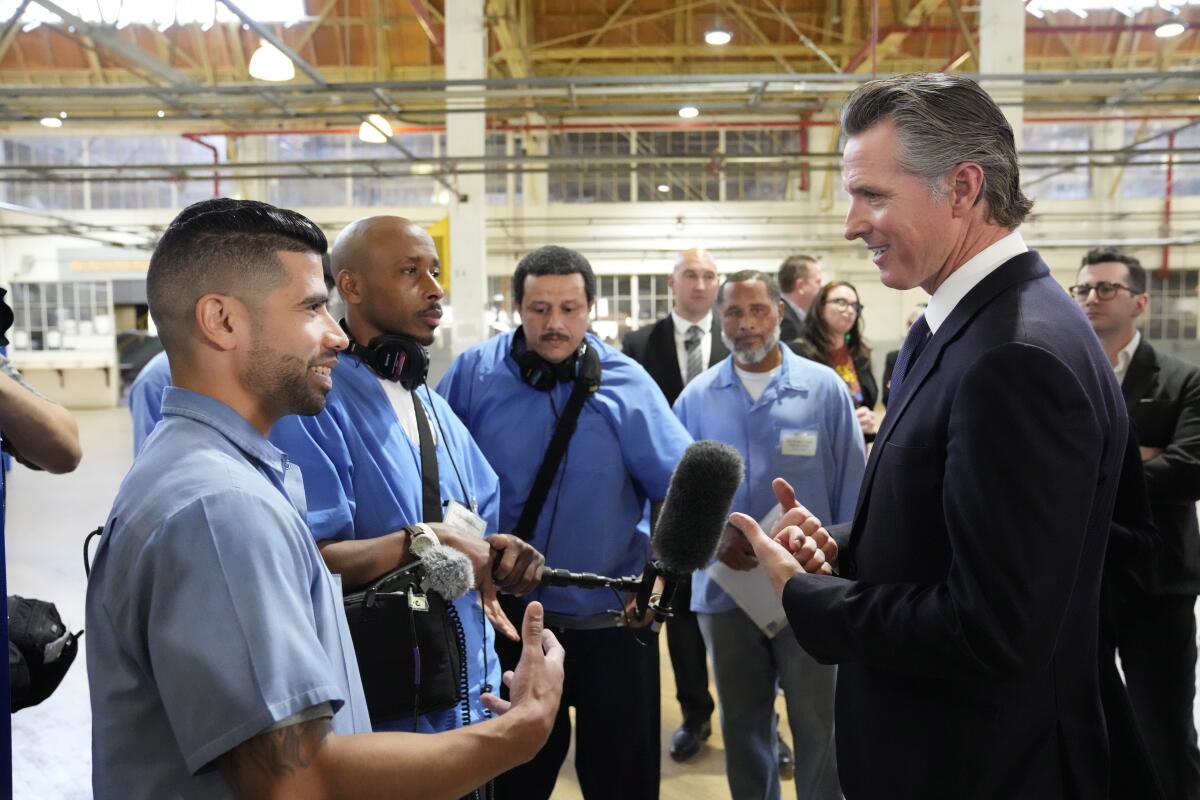

SAN QUENTIN, Calif. — Visiting San Quentin, California’s oldest prison once home to a gas chamber used to execute inmates on the nation’s largest death row, Gov. Gavin Newsom on Friday touted a plan to overhaul the facility in favor of a rehabilitation-centered approach that could become a model for the world.

The facility will be renamed the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center and the more than 500 inmates serving death sentences there will be moved elsewhere in the California penitentiary system. The prison houses more than 2,000 other inmates on lesser sentences.

“We want to be the preeminent restorative justice facility in the world — that’s the goal,” Newsom said from an on-site warehouse that will house his envisioned programs. “San Quentin is iconic, San Quentin is known worldwide. If San Quentin can do it, it can be done anywhere else.”

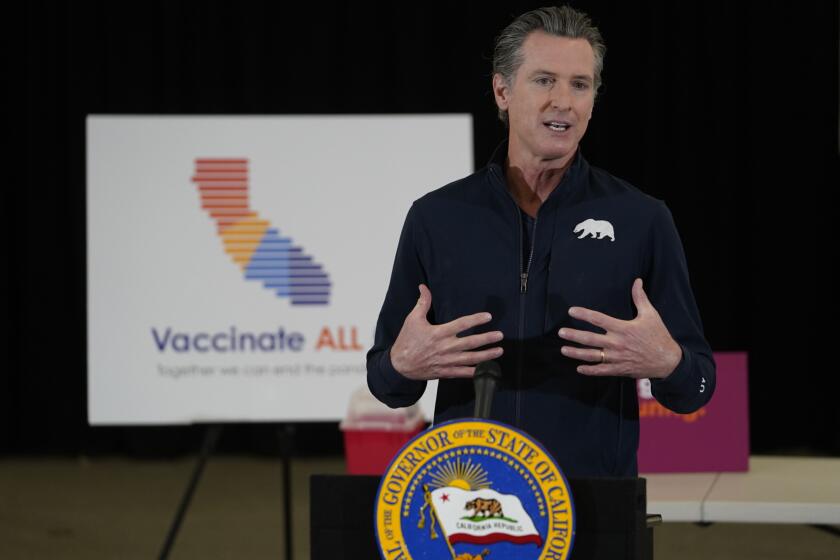

Gov. Gavin Newsom this week will announce plans to remake San Quentin, one of the state’s most storied prisons, using a Scandinavian prison model that emphasizes rehabilitation.

Despite Newsom’s ambitious tone, he offered few concrete details on what the new system would look like and who it would serve. It remained unclear how far the plan would go to reimagine a prison once home to California’s most notorious criminals, like Charles Manson, and the site of violent uprisings in the 1960s and 1970s.

But it has also become known for innovative programs where inmates can get a degree, write for an award-winning newspaper, study the arts and get job training in preparation for reentering society.

A group made up of public safety experts, crime victims and formerly incarcerated people will advise the state on the transformation, which Newsom hopes to complete by 2025. He is allocating $20 million to launch the plan.

The Actors’ Gang Prison Project is celebrating the 40th anniversary of its first-ever production, ‘Ubu the King,’ with a revival directed by Tim Robbins in repertory with new play ‘(Im)migrants of the State.’

The move by Newsom, who recently began his second term, follows his 2019 moratorium on executions, which drew criticism from some who argued he was neglecting the will of voters who in 2016 upheld the death penalty at the ballot box.

From 2020 to 2022, more than 100 inmates with death sentences were transferred from San Quentin to other prisons under a pilot program run by the state. The state spends about $326 million operating San Quentin annually, and Newsom’s administration didn’t say if the new approach would save money.

The latest plan is part of a decades-long transformation of the state’s sprawling prison system, which went under federal receivership in 2005 after a court determined prison medical care was so lacking it amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. A panel of judges later ordered the state to dramatically reduce the prison population because of overcrowding.

About 800 people are released from San Quentin every year, and the goal is to keep them from committing another crime and ending up back in the system, Newsom said.

San Quentin inmate Juan Moreno Haines said the plan will help ensure taxpayer money is being spent to end the ongoing cycle of repeat offenses.

“I’ll ask Californians: What do you want?” he said. “Do you want them to come out of prison better rehabilitated with skills, or do you want them to come out worse than what they were to continually feed this model of criminality?”

Newsom’s office cited as a model Norway’s approach to incarceration, which focuses on preparing people to return to society. Officials from the state’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation toured Norwegian prisons in 2019, where they took note of the positive interactions between inmates and staff. Oregon and North Dakota have also taken inspiration from the Scandinavian country’s policies.

In maximum-security Norwegian prisons, cells often look more like dorm rooms with additional furniture such as chairs, desks, even TVs, and prisoners have kitchen access. Norway has a low rate of people who reoffend after leaving prison.

As of 2015, two-thirds of people convicted of felonies in California were rearrested within two years of release, according to a study by the Public Policy Institute of California. Newsom said efforts to reduce that rate will boost public safety.

Success will be determined “on the basis of people’s willingness and commitment to change themselves, to change their attitudes, and become positive contributory citizens when they’re back in community. We need to help support people along that path,” he said.

The Prison Law Office, a public interest law firm that filed the 2001 lawsuit over California’s prison medical care, has advocated for such an approach to prisons and led tours of European correctional facilities for U.S. lawmakers. On a 2011 trip to prisons in Germany and the Netherlands, Donald Specter, executive director of the law office, said he was shocked to see that they were “so much more humane” than prisons back home.

“While I was there, I thought, ‘Oh my God, we should try to import this philosophy into the United States,’” he said.

Critics of Newsom’s announcement said it follows continued prioritization of people who have committed crimes over victims.

“We’re in a climate where it’s all about the offenders and the criminals and not about the innocent victims that have been victimized, traumatized, harmed — family members that are devastated living without their loved ones because they were murdered and taken away too early,” said Patricia Wenskunas, chief executive officer of the Crime Survivors Resource Center.

Amber-Rose Howard, executive director of Californians United for a Responsible Budget, a group focused on reducing the prison population, isn’t convinced a “Norway model” would work in the United States since the two countries have vastly different histories.

“Newsom should stay on track with closing more prisons, with implementing policies that have been passed that would reduce incarceration and that would get people home,” she said.

Speakers who joined Newsom said they hoped to build on a slew of already successful programs in place at San Quentin. The prison houses the first accredited junior college in the country based entirely behind bars, offering classes in literature, astronomy and U.S. government. Prisoners recorded and produced the hugely popular podcast “ Ear Hustle ” while serving time.

Phil Melendez, a former inmate at San Quentin who now works at the advocacy group Smart Justice California, said the rehabilitation programs the state hopes to expand will set formerly incarcerated people up for success when they reenter society.

“Over the course of [my] time here, I found a new sense of hope,” Melendez said at the prison. “I found healing.”