Israel and Hamas have been here before. How might it end this time?

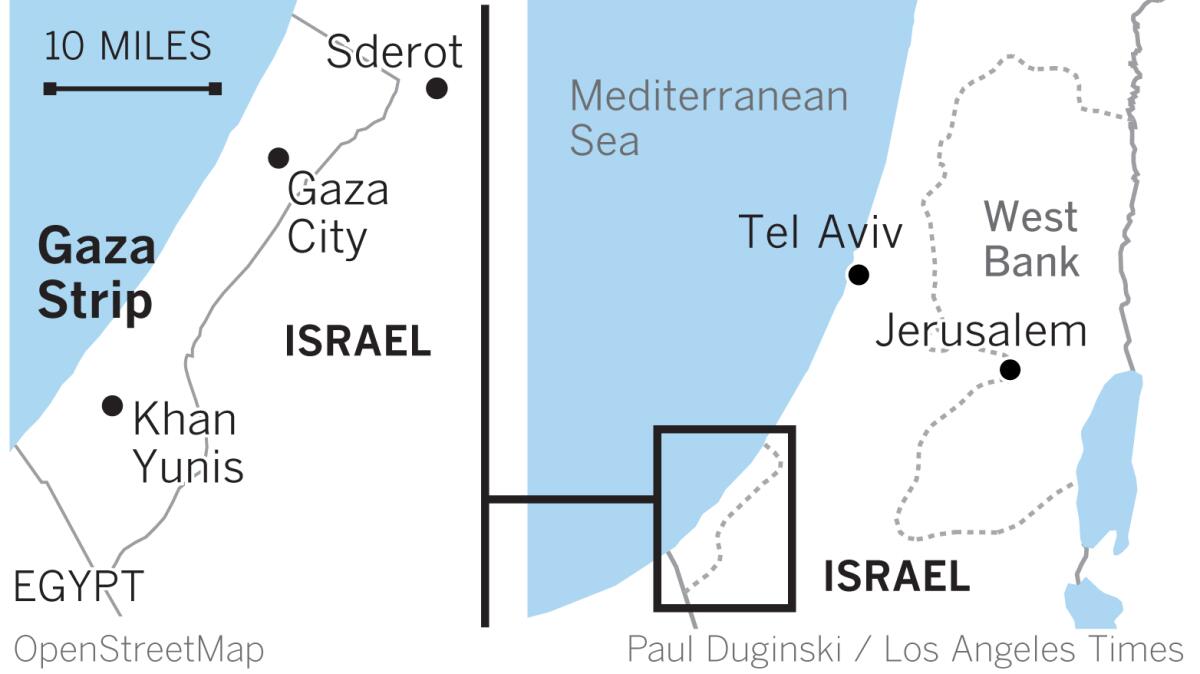

GAZA CITY — The Gaza Strip is once again a blood-soaked battleground, with Israel and the militant group Hamas engaging in their fourth round of warfare since 2008. Now the talk has turned to the conflict’s possible endgame.

On Tuesday, turning aside growing international calls for a cease-fire, Israel’s military declared it would press ahead with bombardment of the Palestinian enclave, and Hamas fired more rockets into Israel, killing two Thai agricultural workers.

Amid deepening suffering in Gaza, the United Nations said that more than 50,000 Palestinians had fled bombardment and that nearly 450 buildings in the territory had been destroyed or damaged. By day’s end, Gaza’s Health Ministry put the number of dead in nine days of fighting at 217, 63 of them children.

At the same time, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appeared to be trying to set the stage for a possible halt to hostilities, saying that Israel’s enemies had learned a painful lesson after enduring more than a week of punishing airstrikes on the impoverished coastal enclave.

“We are hitting Hamas very hard — with enormous scope and intensity — and we will continue as needed,” Netanyahu’s Twitter account said after the prime minister met with military commanders and officials in Israel’s rocket-hammered south.

As international pressure grew for a cease-fire — including a flurry of reports that President Biden, in a Monday call with Netanyahu, encouraged the Israeli leader to wind down the bombardment — Israel’s chief military spokesman said no pullback was being considered.

The Israeli military “is not talking about a cease-fire,” Brig. Gen. Hidai Zilberman told Israel’s Army Radio on Tuesday.

Netanyahu has come under increasingly harsh criticism from commentators who argue that the Gaza campaign was poorly conceived and pointlessly destructive.

“Instead of wasting time in a useless effort to create an ‘image of victory’ while causing death and destruction in Gaza and upending lives in Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu must stop now and agree to a cease-fire,” wrote Aluf Benn, the editor in chief of the daily newspaper Haaretz.

In another sign of renewed unity in the face of the Gaza fighting, Palestinians citizens in Israel — who make up one-fifth of the population — joined in a collective protest with Palestinians in the occupied West Bank. In several West Bank cities, the protests turned violent as marchers clashed with Israeli troops, with three Palestinians killed and more than 140 injured, according to Palestinian officials.

In many respects, the fighting that erupted May 10 has fallen into a pattern reminiscent of previous conflicts: Palestinian militants fire rockets at Israeli cities and towns, while Israel’s powerful airborne arsenal rains devastation on the tiny, impoverished coastal enclave. But some important dynamics have changed in the seven years since the last Israel-Hamas war.

The battles in 2014, interrupted by occasional lulls, went on for 50 days before a cease-fire was struck, and that longevity brought an accordingly heavy toll. More than 2,250 people were killed on the Palestinian side, including hundreds of combatants. On the Israeli side, the civilian toll in 2014 was six — already exceeded in the current fighting — while 67 troops were killed.

That conflict ended in August 2014 with an Egyptian-brokered truce that looked much like the one that ended what was then the previous major Israel-Hamas conflict, in 2012.

Since the 2014 war, Hamas’ rocketry has grown more powerful, putting Israel’s commercial center, Tel Aviv, within easier range, magnifying Israelis’ sense of vulnerability. Militants fire rockets in simultaneous volleys of dozens at a time, trying to overwhelm Israel’s Iron Dome missile-defense system. Even with system upgrades, about which Israel disclosed little, some projectiles manage to get through.

Israel has not sent ground forces into Gaza as it did in 2014, although inaccurate statements from the army last week, mistaken or deliberate, briefly created that impression. Having troops in Gaza would expose soldiers to the risk of capture, which Israelis historically treat as a national trauma.

The outside world is watching this conflict, and while Israel is accustomed to criticism from abroad over disproportionate use of force, the discourse this time has sharpened. The social-justice movement that swept the globe last year after George Floyd’s murder while in police custody in Minneapolis has made the Palestinian cause much more visible than during previous rounds of fighting between Israel and Hamas, and Palestinians in the diaspora, especially the young, have carved out a vocal online presence, chronicling Gaza devastation in vivid posts.

This intense cross-border flare-up between Israel and Hamas is the first real test of a new relationship between Netanyahu’s government and the Biden administration.

The Israeli leader no longer has quite the free hand that he did during then-President Trump’s tenure, when Trump took Israel’s side in virtually all dealings with the Palestinians. President Biden, a longtime backer of Israel’s right to self-defense, has refrained from public criticism of Israel, but he has also called on both sides to “protect innocent civilians” — wording that was read by some as an implicit rebuke of the intense Israeli bombardment of Gaza.

Biden has expressed support for a cease-fire, but the Gaza fighting has caused a split among congressional Democrats, with the party’s progressive wing urging the U.S. leader to do more to halt the fighting. The House Foreign Affairs Committee considered calling on Biden to put the brakes on a $735-million sale of sophisticated precision-guided missiles to Israel.

As in past Israel-Hamas conflicts — 2008, 2012, 2014 — initial diplomatic efforts to stem the fighting have foundered. But a wide range of actors, including the United Nations, Egypt and Qatar, are seeking a halt to hostilities. Egypt brokered the 2014 cease-fire.

Hopes were raised by a virtual meeting Tuesday of European Union foreign ministers, who called for a cease-fire. But Hungary — whose prime minister, Viktor Orban, is a close ally of Netanyahu — foiled a bid by the 27-member bloc to speak unanimously. Nonetheless, EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said there was widespread support for an immediate truce.

For both Israel and Hamas, crafting a victory narrative is a crucial prelude to any move to stand down. Hamas has cast itself as a defender of Jerusalem, the lodestar of Palestinian statehood aspirations, and portrayed the rocket attacks against Israel that it launched on May 10 as payback for Israeli actions at a disputed holy site in the heart of the Old City. Weeks of solidarity protests in East Jerusalem’s Sheik Jarrah neighborhood, in support of Palestinian families who face prospective eviction from their homes, have also met with a harsh response by Israeli police.

Israel, for its part, is saying that Hamas and another militant group, Islamic Jihad, have been dealt a heavy blow by bombardment targeting top commanders and command-and-control infrastructure.

“I have no doubt that we set them back many years,” Netanyahu said Tuesday on a visit to an air base.

But Israel has paid a price as well. In addition to casualties and destruction from thousands of Hamas-fired rockets, the country has suffered its gravest rupture in decades between Jewish and Palestinian Israelis. Communal violence has broken out in several cities, with a series of vigilante-style attacks on both sides.

Special correspondent Salah reported from Gaza City and Times staff writer King from Washington.