20 Indian soldiers killed in clash with Chinese troops at disputed border

BEIJING — The Indian army said Tuesday that 20 of its soldiers were killed in a border skirmish with Chinese troops, the deadliest clash on the two Asian giants’ disputed frontier in more than half a century.

Army officials had said earlier that three were killed in the confrontation on rugged, icy terrain high in the Himalayas, but raised the death toll late in the day, saying that 17 wounded troops had died after being “exposed to subzero temperatures in the high-altitude terrain.”

China and India “have disengaged” from the disputed Galwan area where they clashed overnight on Monday, Indian army officials said. The Chinese government said Wednesday that it is seeking a a peaceful resolution to the dispute.

“Both sides agree to resolve this matter through dialogue and consultation and make efforts to ease the situation and safeguard peace and tranquility in the border area,” foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian told reporters in Beijing.

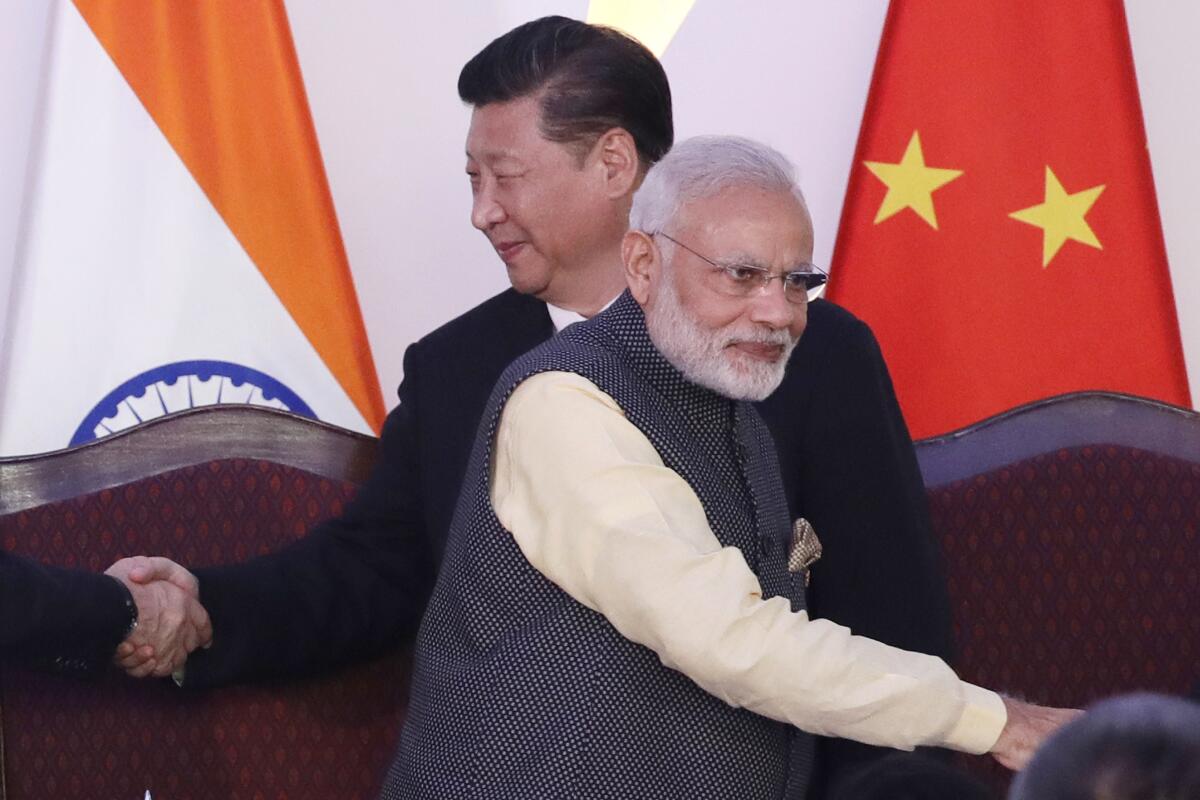

The fighting in the remote Galwan River valley marked a dramatic escalation in tensions between the nuclear-armed rivals, who have long quarreled, mostly peacefully, over their 2,500-mile border. The rise of powerful nationalist leaders in China and India has stoked friction and anxiety in the relationship, especially after each side accused the other of illegal incursions last month and deployed thousands of troops to the border.

Indian security analysts said the two sides were attempting to negotiate a truce in Galwan, one of several locations where troops are facing off, when Indian soldiers accused the Chinese of failing to dismantle all their tents in the disputed valley. A melee broke out involving hundreds of soldiers armed with rocks and clubs. The Indian army described the clash as “a violent face-off” and said Chinese troops had also been killed or wounded, but China did not offer any information on its casualties.

A Chinese military spokesman, Zhang Shuili, blamed Indian troops for crossing the border in breach of a truce and called on India to “return to the right track of resolving differences through dialogue and talks.”

China’s military is much stronger than India’s, but neither side, buffeted by coronavirus outbreaks and other, external challenges, is eager for all-out conflict. Both are economic powers with global ambitions, but for decades they have managed the tensions over their border — left over from a brief war in 1962 — with remarkable restraint, claiming never to fire a shot.

No troops had died on the border in more than four decades, and India has mostly sought common ground with its larger neighbor. The scale of this clash suggests that the uneasy relationship could be in for rockier times.

“I think neither side can hew to the old pretenses that all their disputes are manageable, which is the line that both countries took for the last several decades,” said Ashley Tellis, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The pride that both countries took in not having fired a shot, not having lost lives despite all the disputes — all that now has disappeared.”

A pandemic, an economic downturn and an untested military have forced Beijing to temper calls for war. The move highlights the dangers of harnessing nationalism to bolster party control.

The violence reflects China’s willingness — under the ever-more-muscular leadership of President Xi Jinping — to defend or assert territorial claims while its regional neighbors are busy battling the coronavirus.

Claiming to have squashed the virus through draconian containment measures, Beijing has denounced international efforts to investigate the origins of the outbreak and has continued its aggressive naval buildup in disputed areas of the South China Sea.

“China truly doesn’t want to have conflict with India but is also unafraid of conflict with India,” Hu Xijin, editor of the nationalist tabloid Global Times, wrote Tuesday on Weibo, a Chinese social media site.

“Hope India remains self-aware and doesn’t forget the lessons of history,” Hu wrote. “There are no possible benefits to themselves or to the region if they provoke more conflict at the China-India border. Hope they don’t seek further lessons from China.”

In a tense standoff between nuclear-armed nations that threatens to destabilize Asia, both sides are digging in, with one warning of unspecified “countermeasures” and the other saying it won’t be bullied.

According to Indian security analysts, Chinese troops crossed the border at several points hundreds of miles apart last month, brawling with Indian soldiers and traversing rugged ground to penetrate at least two miles deep in some areas. The Chinese have fortified their positions with bunkers, trenches and roads, leading Indian officials to conclude that the People’s Liberation Army is attempting to redraw the boundary unilaterally.

Thousands of Chinese troops were sent to the area, backed by tanks and armored vehicles, prompting India to deploy large numbers of reinforcements. Yet for weeks, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government played down the tensions. Indian and Chinese commanders met several times in recent weeks, although neither side appeared to budge from its position.

The trigger for the Chinese incursions appeared to be an increase in road construction by Indian forces. Chinese analysts said the road-building crossed into Chinese territory, which India denies.

Han Hua, professor of international studies at Peking University, said India’s infrastructure buildup occurred without enough “constructive communication” to assuage China’s concerns.

“They are building roads, and they are building a lot,” Han said. “It’s hard to say if they’re on Chinese territory or not. It’s disputed. This conflict is not an accident — it was inevitable.”

The disputed border, known as the Line of Actual Control, cuts through parts of Kashmir on the Indian-held side and Tibet on the Chinese side. Tensions have been simmering since 2017, when Indian troops blocked Chinese construction crews and border guards who were attempting to extend a road through territory claimed by the tiny kingdom of Bhutan. The result was a two-month standoff that ended after both sides agreed to withdraw their forces from the plateau.

Especially alarming to New Delhi was that Monday’s clash occurred in a valley — between the Indian region of Ladakh and the Chinese territory of Aksai Chin — that India believed was firmly in its possession.

Chinese troops occupied the Galwan valley during the 1962 war, then withdrew, but its status has never been resolved. In the Chinese military statement Tuesday, Zhang said the valley “has always belonged to China.”

Ajai Shukla, a former Indian army officer and a newspaper columnist, said the Chinese had stationed troops on surrounding hilltops, where they overlook a road leading to an important Indian airstrip.

Elsewhere along the border, the People’s Liberation Army has deployed artillery units and is building huts, suggesting it “is preparing for a long confrontation,” Shukla wrote in the Business Standard newspaper.

Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi, said that “under Xi, China is increasingly seeking to redraw its land and sea frontiers.... Its success in the South China Sea, where it has fundamentally changed the status quo without firing a shot, has emboldened its moves in the Himalayan borderlands.”

Chellaney said the lack of significant international pushback over China’s mass incarcerations of Muslim citizens in Xinjiang and its crackdown in Hong Kong had also emboldened Beijing.

“As long as China pays no significant geopolitical price for its expansionist agenda,” he said, “it will continue on the present path.”

Chinese analysts portrayed India as the aggressor, drawing comparisons to Modi’s decision last year to revoke autonomy for Kashmir, the Muslim-majority border territory that is at the center of a bitter dispute with Pakistan.

Liu Zongyi, research fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, said Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda used “attack as a defense, not just toward Pakistan but also toward China.”

Chinese nationalism also makes it difficult for the People’s Liberation Army to withdraw, Liu said, arguing that China had already “given up too much” to Indian control in the border region. “We can’t pull back more,” he said.

Su reported from Beijing and Bengali from Singapore. The Associated Press contributed to this report.