Exclusive: Inside the NFL schedule war room — ‘making everybody equally disappointed’

- Share via

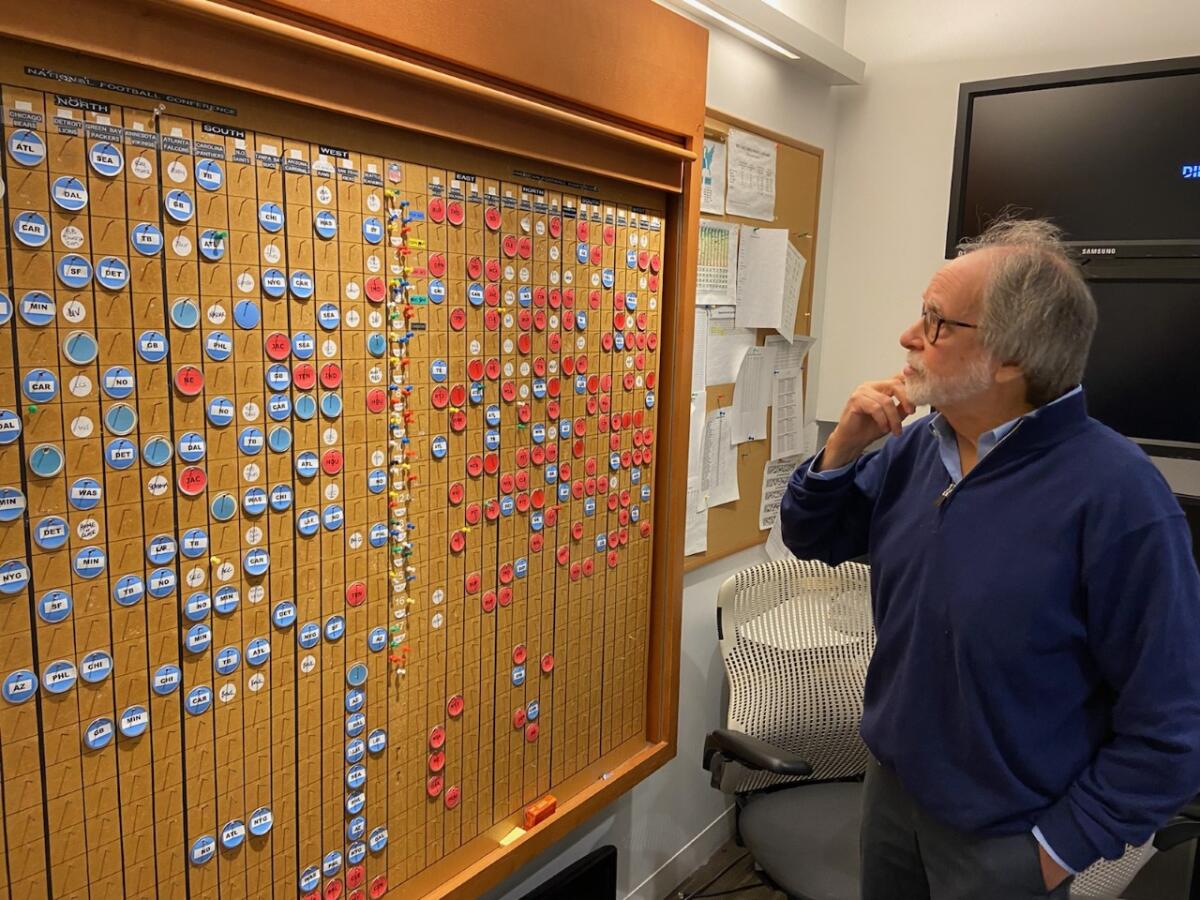

Michael North, vice president of NFL broadcast planning, shows how the NFL television schedule was prepared in the days before computer software automated much of the process.

- Share via

NEW YORK — This is their Super Bowl.

The team of five people who build the NFL schedule will unveil their latest masterpiece this week, with the news trickling out in the coming days leading to Thursday’s release.

If all goes as planned, everyone will be unhappy.

“Every schedule has its warts,” said Michael North, who has been putting them together for 25 years. “Our job is to figure out which ones are truly onerous and unplayable, and which ones are, ‘Well, this isn’t ideal, but look at all the good that comes with it.’

“If any one of them jumps off the page as this guy is way too happy or way too disappointed, that’s probably not our best schedule. It’s all about making everybody equally disappointed.”

Naturally, everyone involved wants to feel good about the final product, and this collection of beautiful minds — led by Howard Katz, senior vice president of broadcasting — spends months analyzing, debating and reshuffling a Rubik’s Cube of 272 games aimed at maximizing viewership and fan interest while trying to maintain fairness for the teams.

NFL draft 2022: Every team was looking to improve via draft picks. Los Angeles Times Pro Football Hall of Fame writer Sam Farmer assesses each team’s performance.

“One of the things people don’t realize is how sophisticated our scheduling process is,” NFL commissioner Roger Goodell told The Times. “We’re considering more variables, more factors than we’ve ever been able to do. Part of that is the technology, and part is our ability to learn every year and get better at it. That’s why the schedule is so much better.”

The process of searching for that closest-to-perfect schedule — like locating a particular grain of sand on the beach — requires co-opting as many as 4,000 computers around the world to work the problem around the clock.

Trillions of schedule combinations are crunched to find the ones that conform with more than 25,000 “rules,” such as this stadium isn’t available on this date, or no team can have two three-game road trips.

This year, Prime Video becomes the exclusive home of “Thursday Night Football,” the latest in a crowded field of broadcast partners elbowing for the best matchups.

“The puzzle just becomes more complex every year,” Katz said. “We have more and more computer power running at this, then we get into the process.”

Another difference this year is for the first time, the season kicks off with a Thursday night game in Los Angeles, thanks to the Rams winning the Super Bowl.

The Chargers’ defensive rebuild continues with the signing of linebacker Kyle Van Noy, a veteran of eight NFL seasons who played in three consecutive Super Bowls.

It used to be that Week 1 would have been determined weeks ago. But now, because computers might spit out competing schedules that look completely different, the matchup for the Sept. 8 opener isn’t locked until the end of the process.

As of the middle of last week, the group said, the visiting team for the opener was still in flux.

“Now we can teach the computer that Dallas is a good option, Denver’s a good option, Buffalo, any of the NFC West opponents,” North said. “Pick whichever one you want and go down that road, and let’s see what the result and the schedule looks like.”

The NFL is fiercely protective with its scheduling information, so trying to decipher the plan from the outside is mostly a process of elimination. It would seem the most logical opening opponent for the Rams would be Buffalo or Denver.

Dallas played in last season’s kickoff opener at Tampa Bay and was the Rams’ opponent in the first game at SoFi Stadium and the first preseason game back in Los Angeles. The Cowboys have gotten a turn.

San Francisco would be an intriguing choice, but with the way 49ers fans flooded SoFi last year, all that red could be bad optics for the defending Super Bowl champions at their home venue.

The process makes the old system seem so antiquated and quaint, back when NFL executive Val Pinchbeck unscientifically would assemble the schedule by hand on a giant pegboard, working front-to-back and back-to-front, then stuffing a bunch of games in the middle.

The room where decades of subsequent schedules were built is now named in honor of Pinchbeck, who died in 2004. That room is now a relic too, with everyone migrating to video calls during the pandemic and staying with them once they proved more efficient.

The Val Pinchbeck Room is small — maybe 10 by 15 feet — on the fifth floor of the league’s Park Avenue headquarters. It’s one of the few offices with frosted glass, and precious few people have a key card to access it. For years, it was permanently stocked with jellybeans and Mountain Dew and smelled of too many people working too hard for too long.

At one end, Pinchbeck’s artifact of a pegboard. At the other, a white board filled with a convoluted diagram that looks like something out of “Homeland,” but is meant to explain some aspect of networks and early Sunday games. In the middle is a small table that faces a wall of TVs, and the “clubhouse leader,” that year’s best schedule to date, is taped to the lone glass wall.

“We started putting up the leader in the clubhouse, so that if Roger came down and banged on the glass, he’d have something to see,” Katz said. “There’s a lot of anxiety until we have a playable schedule.”

Donald Parham Jr., the Chargers tight end who says his life flashed before his eyes in the end zone, recounts the injury from a fall that many feared might leave him paralyzed.

The first of those didn’t arrive until April 17 this year, stomach-churningly late in the game. All this technology allows the Katz crew to be increasingly discerning, a blessing and a curse. The team is composed of Katz, North, senior director of broadcasting Charlotte Carey, director of broadcasting Blake Jones and manager of broadcasting Nick Cooney. Onnie Bose, vice president of broadcast operations, and Hans Schroeder, executive vice president of NFL Media, are also heavily involved. Nobody clocks out. It’s all schedules, all the time.

“My wife gets mad at me,” Jones said. “It’s usually me sitting in a corner staring off into space. People just think I’m completely aloof and no fun to be around. We’re just thinking about all these things, trying to figure it all out.”

As with those computers, the group works around the clock. North is scouring readouts past midnight and into the early morning hours, then hands those duties to Carey.

“As the mother of a 2-year-old, I like to think of it as babysitting,” she said. “Mike takes the night shift, and he watches the computers until 3 or 4 a.m. and doesn’t sleep. I get up around 5 and take it from there.

“It’s a little like Groundhog Day. We come in, we all meet, look at schedules. Howard says, ‘I like this. I don’t like that. Let’s change these rules.’ We write new rules and software. We say, ‘Go!’ and the software’s off and running.”

There’s still a pandemic effect too. All the music tours are coming back after a two-year hiatus, meaning stadiums aren’t always available.

“So every time a team sends us a request and says, ‘Hey, can you put us on the road in Week 2, we’ve got Elton John or Lady Gaga,’ you think, ‘Yeah, sure,’” North said. “One week for them shouldn’t be an issue for the league office, right? Just block it out.

“But then the team says, ‘Don’t ruin our schedule as a result. We still want to open at home. Just put us on the road in Week 2 and we’ll come home again in Week 3.’ But if 16 clubs have similar asks, that becomes a pretty big constraint on a pretty challenging puzzle which is only getting harder.”

The movement of players matters too. That’s why the schedule isn’t announced until after the draft, as a new influx of players can make matchups considerably more interesting. Denver got more intriguing with the addition of Russell Wilson. Same for Miami with Tyreek Hill and Indianapolis with Matt Ryan.

“When Tom Brady retired, we were concerned about the strength of the NFC package because there were so many terrific Tampa Bay games we were looking at,” Katz said.

The Rams did not have many high NFL draft picks, but they felt comfortable enough as champions to sit back and add depth to their talented roster.

“Then a month later he un-retires and we sort of started all over again.”

Next year, the life of the schedulers will get more complex. As it stands, NFC games belong to Fox, and AFC games belong to CBS. That changes in 2023 when all games essentially become free agents.

Just because an NFC team is on the road, for instance, that will not guarantee a game will belong to Fox. Every game will be a jump ball among the networks.

At the end of the season, when everything is done, the NFL will have to make sure it hits certain minimums for all of its partners, so there will be a certain number of times each AFC team will need to land on CBS. But the notion of, “Hey, it’s Miami at Baltimore. Must be a CBS game,” will be done.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

This much will never change: the complaints.

“Everybody hates their schedule,” North said. “That’s the one thing you can count on. Sometimes it’s emotional. Sometimes it’s legitimate and based in some historical data and win percentages that we should go back and look at. And we say to ourselves, `That’s probably something we shouldn’t do again.’

“Every year we learn. We listen to our constituents. And even though you’re not supposed to read internet comments, we listen to our fans. We try to figure out which of these team inequities are truly onerous and which are just a bad break.”

Either way, the teams will have something to say.

“They’re not shy,” North said. “And they have very long memories.”