A push to recognize the statistics of Black players from baseball’s era of apartheid

- Share via

Move over, Babe. You too, Ted Williams.

More than six decades after taking their last swings, two of baseball’s top sluggers could soon be dropping down the sport’s most hallowed leaderboards to make room for Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston and Turkey Stearnes.

Major League Baseball is considering giving major-league status to six long-defunct Negro Leagues, where 35 Hall of Famers played during the sport’s segregated era.

“It’s the right thing to do,” said Scott Simkus, a former Chicago limousine driver who spent much of the last two decades helping build a statistical database of the Negro Leagues by tracking down and chronicling box scores of once-forgotten games. “It’s long overdue, but it would be righting a wrong. It would be giving the Negro Leaguers full citizenship as professionals.”

Not everyone agrees.

“Negro Leaguers should be compared against themselves,” said Larry Lester, a pioneer of Negro League studies and the chairman of the Society for American Baseball Research’s Negro Leagues committee. “I don’t think it’s fair to rank the Negro Leaguers and the major leaguers together for the simple fact they never played against each other.”

Reflecting on the 100th anniversary of immensely popular Negro League baseball is particularly instructive during this time of racial reckoning.

When Major League Baseball Commissioner William Eckert in 1968 convened the Special Baseball Records Committee to determine what constituted a “major league,” the five white men on the panel chose six leagues that mostly banned Black and Latino players between 1876 and 1947, before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. The Negro Leagues were not discussed.

Now, a century after their founding, the push to recognize the Negro Leagues is gaining momentum, advanced in part by the Black Lives Matter movement. During the past major league season, players, coaches and umpires sported 100th anniversary Negro Leagues logos that also appeared on bases and lineup cards during an August celebration of Black baseball, and teams wore throwback Negro League uniforms in some games.

But revising record books would be far more meaningful: recognition that the accomplishments of Negro Leagues players were equal to those of their white contemporaries.

“The Negro Leagues merit consideration as majors,” said John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian.

An MLB spokesman confirmed that discussions are continuing about whether to integrate the statistics of six Black leagues with those from the leagues already granted major-league status. The first step in that process would be to accept the work of three generations of statisticians who have been forensically poring over archived materials.

“We accept 19th century numbers without so much as batting an eye, but with the Negro leagues, people have been like, “Woah! Slow down! Not so fast with those Negro league stats!”

— Scott Simkus, Negro Leagues stats researcher

“We’ve put together something that’s the first really good, comprehensive statistical encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues,” said Gary Ashwill, a North Carolina researcher who helped spearhead the effort. “The fact that that exists is probably a key contributor to the fact that the discussion is even happening right now.”

Merging the numbers has inherent problems, but it’s a challenge that’s been met before — when statistics from the National and American leagues were integrated with those from the Players League, American Assn. and Union Assn., all of which folded in the 19th century.

Pud Galvin, baseball’s first 300-game winner, pitched in four different leagues before 1891, starting his career at a time when pitchers threw underhanded and the distance from the mound to the plate varied widely. Billy Hamilton, a lifetime .344 hitter, played in those days too, retiring in 1901. Yet their numbers had been allowed to stand against those of Clayton Kershaw and Mike Trout.

“We accept 19th century numbers without so much as batting an eye, but with the Negro Leagues, people have been like, ‘Whoa! Slow down! Not so fast with those Negro League stats!’” Simkus said. “Why? Racism, plain and simple.”

No sport reveres its numbers and history more than baseball, so adding the totals of 3,448 Negro League players to MLB’s record book is bound to be controversial — especially at the top.

Because the Negro League seasons were often less than half the length of a major league season, Black baseball didn’t run up big “counting stat” totals — Stearnes, a five-tool outfielder, led the Negro Leagues in career home runs with 196. That total has been surpassed by 364 major leaguers. And Willie Foster’s Negro Leagues-best 140 pitching wins are less than a third of Cy Young’s 511.

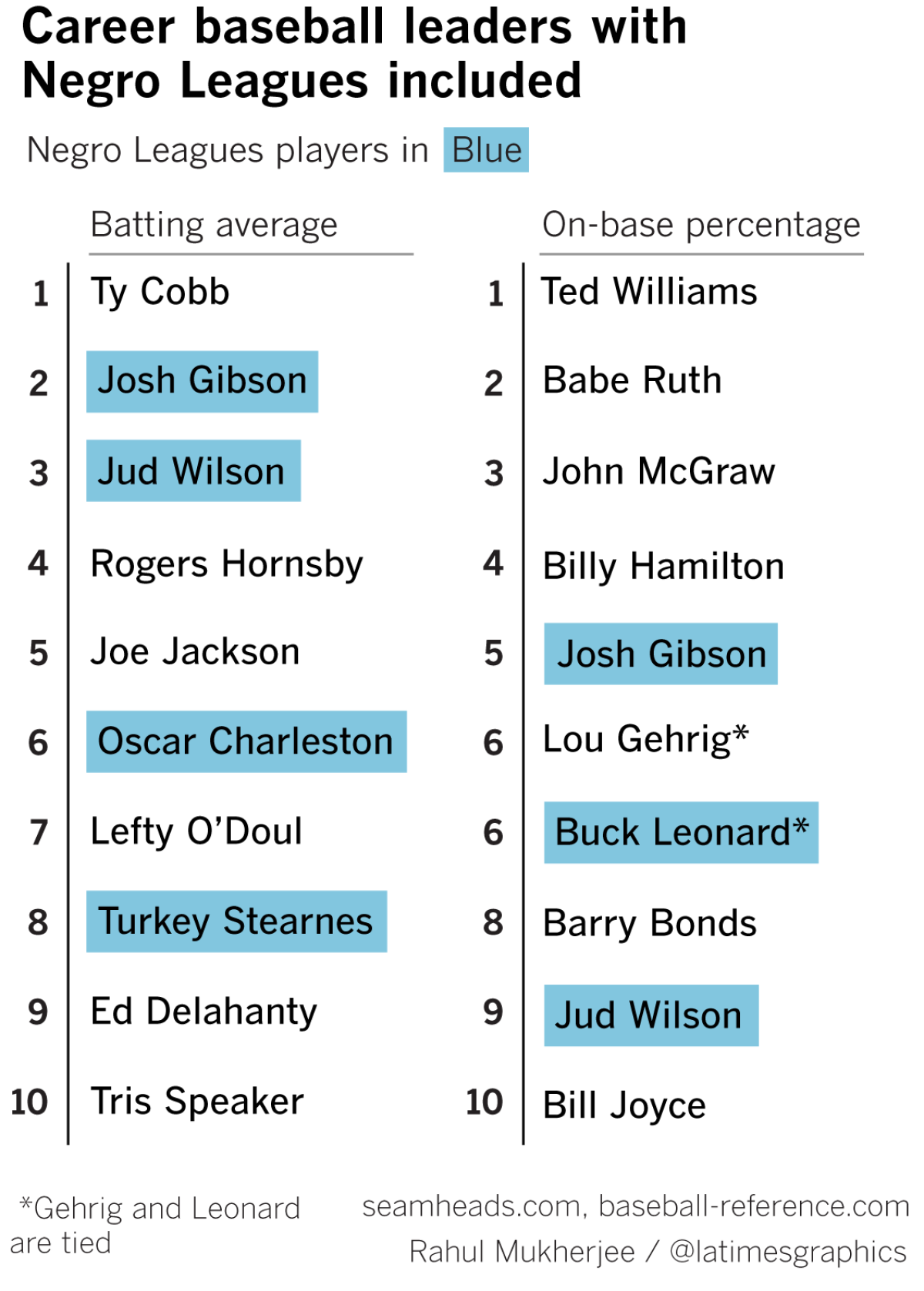

But the leaderboards for averages, such as on-base percentage and slugging percentage, could change dramatically.

The Negro Leagues database, posted online at seamheads.com, shows four hitters with a high enough average and enough plate appearances to push Ruth and Williams out of the top 10.

Gibson, Buck Leonard and Jud Wilson would be among the top 10 in on-base percentage, replacing Ty Cobb, Jimmie Foxx and Rogers Hornsby.

Also, the merging of stats from big-leaguers who began their careers in the Negro Leagues would boost the hit total of Willie Mays — 12th on the all-time list — by 17 to 3,300.

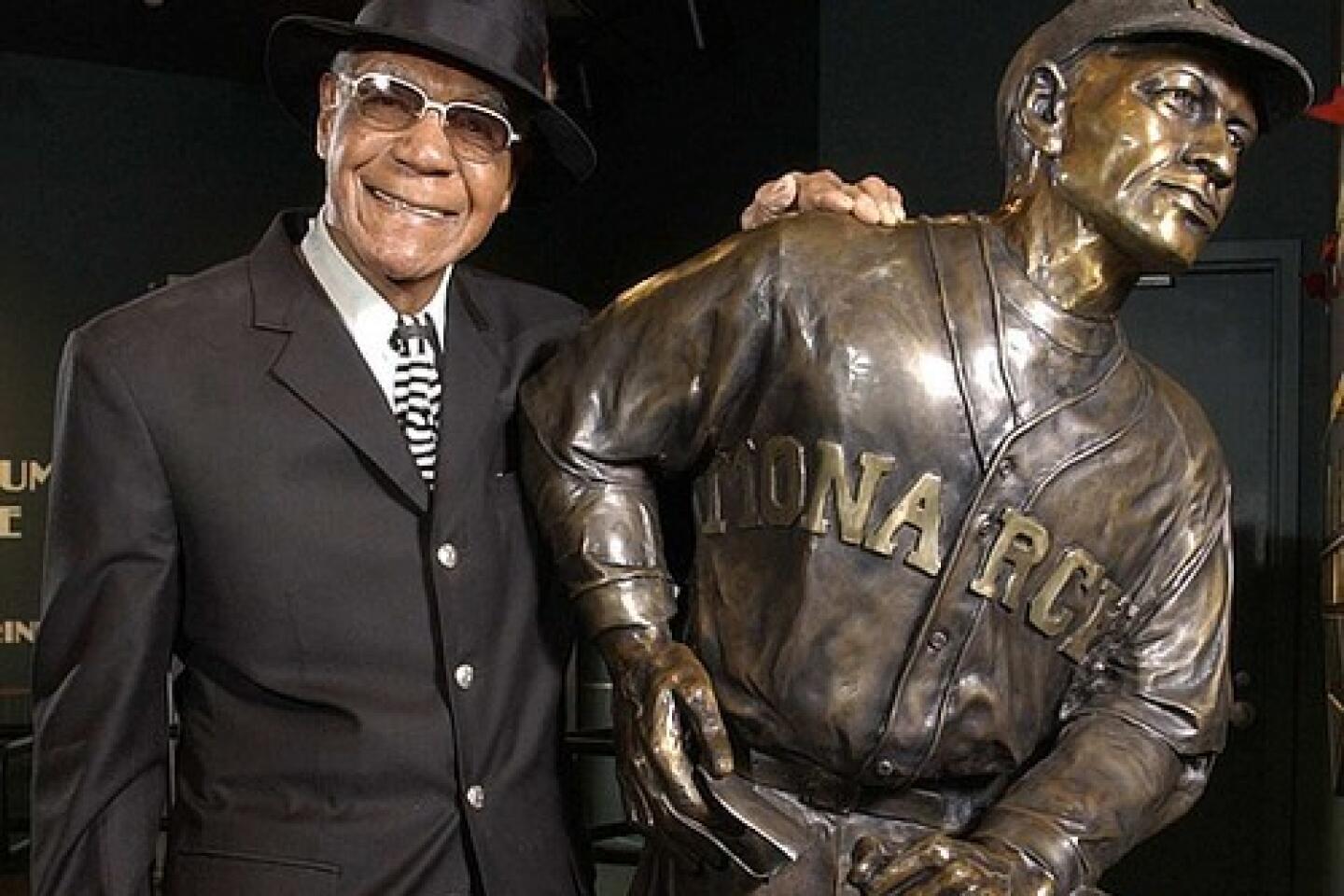

“You’re going to get some hate against it. Because now, in the minds of some, you’re diminishing those great white ballplayers that forever we’ve been told were the absolute best,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo. “And it doesn’t diminish them at all. It introduces some other guy who was just as good.”

Professional Black baseball dates to 1885 and the founding of the Cuban Giants, who began play 16 years before the New York Yankees or Boston Red Sox. In 1887, the International League, a top-tier minor league, voted to ban the few Black players it had, ushering in the so-called “Gentleman’s Agreement,” an unwritten rule that segregated professional baseball for the next six decades.

In response, Black players formed parallel leagues. In their heyday, from 1920 to 1948, the Negro Leagues were among the most successful Black-owned businesses in the U.S., with teams in many major cities on the East Coast and the Midwest.

The Negro Leagues staged their own all-star games and World Series and frequently sold out cavernous major league ballparks. Players such as Gibson, Charleston, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Martín Dihigo, Judy Johnson and Willie Wells — all inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. — routinely bested white stars in barnstorming games or in Latin American winter leagues, where teams were integrated.

“When you look at the head-to-head competition, the Black teams won more than they lost against white major leaguers,” Simkus said.

That Negro Leaguers were as good or better than their white counterparts was apparent when Black players began following Jackie Robinson into the majors. Between 1949 and 1959, nine of the 11 National League MVPs — including Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks — were former Negro Leagues players.

Yet, much of Negro Leagues history has been clouded by tales that are only partly true. For example, Gibson’s Hall of Fame plaque says he hit “almost 800 home runs;” the Seamheads database credits him with just 194 in Negro Leagues play. Legend also has it that Gibson hit 84 home runs in a year; research shows he never hit more than 20 in a Negro League season.

Deciding which games should count has been a major issue. Although Negro League teams frequently played fewer than 80 league games a season, to make ends meet they sometimes played another 100 or more against semipro teams or incomplete teams of white minor leaguers.

Lester has crunched the numbers for the heart of the Negro League era and found the variation from accepted major league stats to be less than 1%.

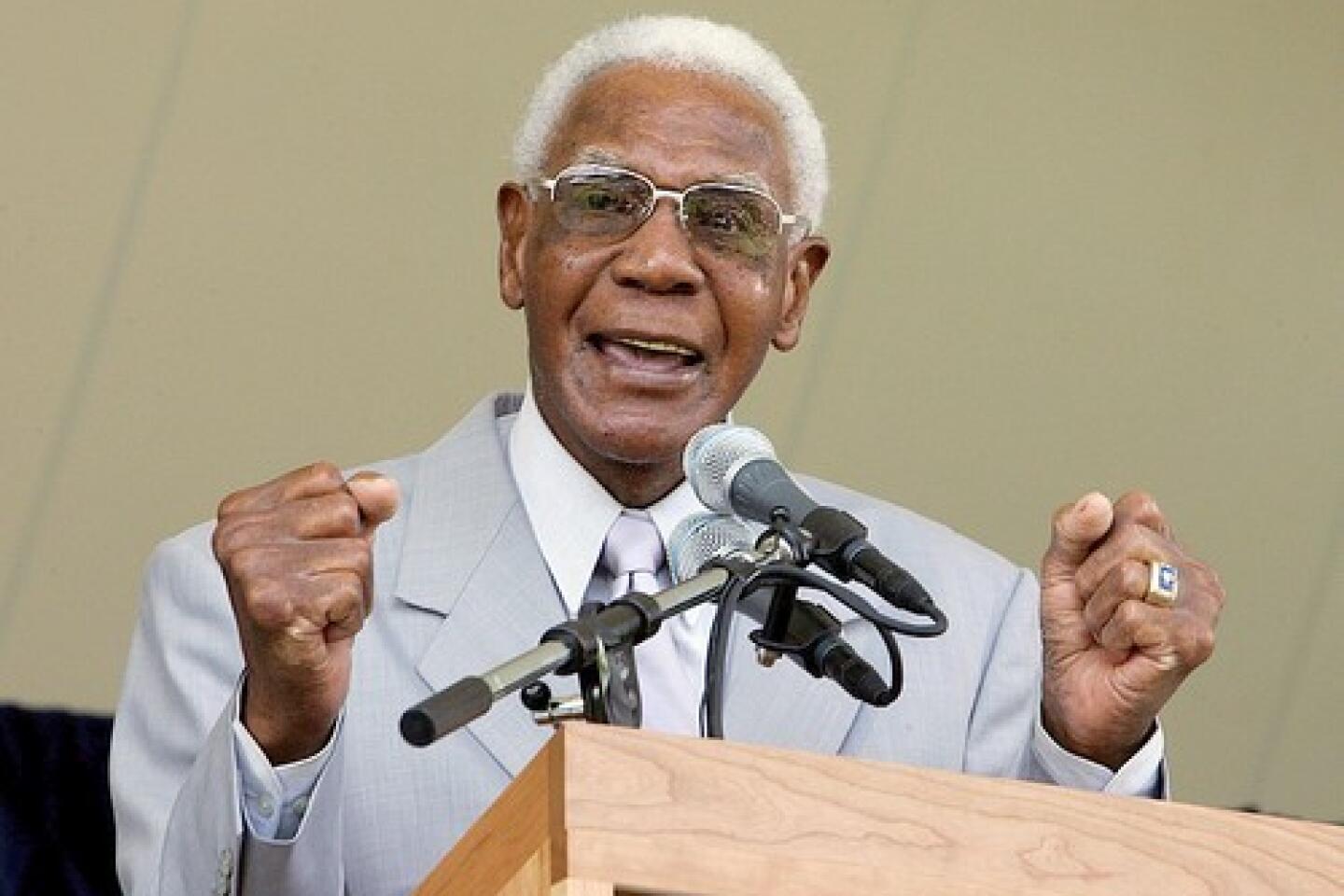

“I don’t say the Negro League stats are better. I say they are the equal of Major League Baseball,” said Lester, 71, whose day job focuses on the research of African American sports history. “But to rank anybody 1 through 10, that’s more subjective than objective because we don’t know what those stats would have been if we had integrated baseball. Those stats were achieved during apartheid baseball.”

For starters, living and playing conditions were disparate. Major leaguers traveled by train, slept in hotels and played in pristine ballparks; Negro Leaguers often slept in buses between endless doubleheaders, sometimes playing at fields that resembled a pasture.

“That’s why it’s so difficult to compare stats,” Lester said.

There’s no remedy, short of a time machine, for that. But researchers such as Lester and Ashwill have come up with formulas and calculations to fill holes in the research, allowing them to determine how many runners were left on base and even who made the last out in a game even when that information wasn’t documented.

Because Negro League box scores weren’t always printed in major newspapers, researchers have dug through microfilm files of Black newspapers, such as the Baltimore Afro-American, Pittsburgh Courier and Chicago Defender.

“There’s no Sporting News, there’s no central source for box scores,” Simkus said. “The game was only covered in one damn newspaper. So we have to go to that town, go to the historical society, or go to the library and find the games and find the box scores. That’s why this has taken forever.”

A fourth-generation Chicago Cubs fan, Simkus, 50, got interested in the Negro Leagues as a grade schooler after reading Robert Peterson’s groundbreaking book “Only the Ball was White.” He got hooked on researching the leagues years later while scouring Chicago Tribune archives for the box score of a game his grandfather played against the Cuban Stars.

Simkus, whose office at the limousine company is full of Negro Leagues memorabilia, has done more than compile statistics. He wrote “Outside Baseball: The Weird World of Hardball on the Fringe,” contributed to Peterson’s “The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues,” an academic reappraisal of Black baseball, and put together a Negro Leagues version of the classic Strat-O-Matic board game in 2009.

Simkus says the work taught him how important major league recognition would be for the families of Negro Leagues veterans, few of whom are still alive.

“Many of the players are gone, but their descendants are here, the nieces and nephews, grandchildren who stumble across the Seamheads website and say, ‘Hey, my grandfather or uncle was part of something special,’” he said. “We’re rebuilding another segment of history for African Americans who, sadly, a lot of their history, because of slavery, you can only go back so far. Here’s something they can be proud of, and something we can all be proud of.”

Ashwill, 53, a freelance editor of academic books and journals who has been compiling and cross-checking Negro League stats since his days as a graduate student at Duke in the 1990s, likened the task to being a forensic investigator.

“A lot of people just succumb to the belief that if it didn’t happen in the major leagues then it didn’t happen. Because it was white it had to be better.”

— Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

“First you have to establish a tentative schedule, to get an idea of where teams were going,” he said. “Then you target the local papers in those cities. You’ll get box scores that conflict. The accompanying game story might say someone hit a home run; you look at the box score and there’s no home run.”

The fact that so many newspapers and historical documents are now digitized has cut down on travel, Ashwill says, but it hasn’t lessened the detective work.

“It’s not just data entry,” he said. “You’re really analyzing the game.”

Ashwill, who grew up in Kansas City, the heart of the Negro Leagues and where Robinson, Banks, Bell, Stearnes and Satchel Paige once played, also discovered the Negro Leagues through Peterson’s book. He fell in love with the numbers side of the game by reading Bill James, who coined the phrase Sabermetrics to define “the search for objective knowledge about baseball.”

“I wanted to marry that kind of analysis to my interest in the Negro Leagues. And my interest in the Negro Leagues was mainly because it was so unknown,” Ashwill said.

Major League Baseball’s recognition of the numbers Negro Leaguers compiled could boost the profile of those players and leagues, he added, while contributing to the national conversation on racial equality.

“That’s intimately tied, the whole question of justice for these players and racial justice in the country at large,” Ashwill said. “A large part of how white supremacy has worked in this country is by obscuring and hiding things, hiding what really happened, and keeping us from knowing what our real history is.

“So to me, it’s like just trying to document everything and get it straight and get it clear, as clear as possible, anyway. That in itself is an attempt to bring about some kind of social justice, historical justice.”

When Jackie Robinson integrated baseball in 1947, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was a year short of graduating college. Kendrick, the Negro Leagues Museum president, said it was baseball, the national pastime, that helped ignite a national passion for social justice that still has not been realized.

“No sport holds to its history like baseball does,” he said. “A lot of people just succumb to the belief that if it didn’t happen in the major leagues, then it didn’t happen. Because it was white it had to be better.

“This is a civil rights museum that is seen through the lens of baseball,” he continued. “This is what started the ball of social justice rolling in our country. Baseball has always played a role in bringing us together.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.