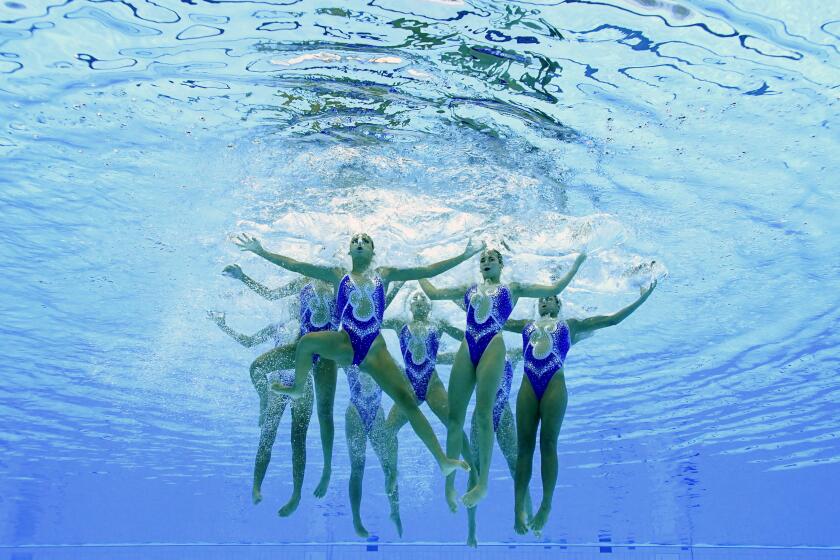

The longer you stay underwater, kicking your feet, sculling your arms against all that heaviness and bright blue, the worse it gets. Legs cramp, fingers tingle and lungs burn as the brain screams for oxygen.

The trick is staying calm, accepting the pain.

Daniella Ramirez explains this in the simplest terms. Built small and thin, her dark hair tucked beneath a swim cap, she suggests pressing your tongue to the roof of your mouth so you don’t panic and gulp water. One of her teammates, Natalia Vega, says, “It might sound silly but relaxing your face helps.”

All the women on the U.S. artistic swimming team have a favorite method for holding their breath longer.

Their sport — which used to be known as synchronized swimming until officials changed the name several years ago — has been dismissed as the Olympic version of some Esther Williams film from the 1940s and 1950s and famously mocked by Martin Short and Harry Shearer in a “Saturday Night Live” skit. The Kabuki-style makeup, forced smiles and gelled hair, the nose clips like your aunt used to wear in the pool. Who could take it seriously?

As U.S. artistic swimmer Anita Alvarez performed at the world championships, her coach noticed something was wrong: Alvarez was at the bottom of the pool.

But no one laughed when American swimmer Anita Alvarez pushed herself too hard at the world championships in June, passing out during solo competition, her body sinking, arms dangling lifeless as a coach pulled her out. “When I was lying there on the side of the pool, I started to hear the doctors and my teammates in the stands,” Alvarez recalls. “I started to feel pain everywhere and I realized I wasn’t breathing, so I took a breath.”

The incident went viral, shedding new light on a sport every bit as athletic as gymnastics with the added challenge of, well, being submerged. Alvarez wonders if “people would start recognizing how difficult it is.”

Months later, on a warm autumn morning, she and the rest of the national team gather for practice at a pool shaded by tall pines on the edge of the UCLA campus. Their easy chatter dies down as they slip, one-by-one, into the water.

With a new season approaching, the Americans are fighting to become competitive with the powerful Russians and Chinese, hoping to contend for a medal by the time the Summer Olympics return to Los Angeles in 2028.

In artistic swimming, that means striving to perfect your every kick, every stroke, every theatrical pose. It means getting comfortable with not breathing.

With something this odd and technical and obscure, it probably makes sense that Benjamin Franklin is recognized as an early practitioner. The statesman was a devoted swimmer, noted for his “ornamental” display on a visit to the Thames River in 1726.

“I stripped and leaped in the river … performing on the way many feats of activity, both upon and under water, that surprised and pleased those to whom they were novelties,” he wrote.

The so-called natationists of the 1800s entertained crowds at “water ballets” with all manner of tricks and acrobatics. Around the turn of the next century, an Australian actress named Annette Kellerman toured the U.S., donning a one-piece bathing suit instead of traditional pantaloons and performing inside a glass tank. Private clubs formed in various countries, devising rules to transform entertainment into a new type of competition that shifted to women only.

Southern California soon became entwined with the odd sport.

Kenny Gaudet helps redefine the ideal artistic swimmer: “I like how I can express myself in the water rather than on land.”

Hollywood musicals such as “Million Dollar Mermaid” and “Dangerous When Wet” helped synchronized swimming build a small, devoted fanbase through the 1950s. Local officials brought the sport into the Olympic fold, adding it to the program for the 1984 Los Angeles Games. “Are you sure?” U.S. swimmer Tracie Ruiz asked when told by a Times reporter. “I can’t believe it.”

Four decades later, the U.S. program has moved its year-round training center to UCLA, rotating among several pools on campus. Yet for all its history on the local and global scene, artistic swimming remains largely a mystery.

“It’s very difficult to understand the water and how to use it as support,” U.S. coach Andrea Fuentes says. “This is crazy if you think about it, no?”

“Things have evolved very much since my time — it’s more acrobatic, more athletic. You need eight to 10 hours a day, year-in and year-out, to become a good artistic swimmer.”

— Nicole Hoevertsz, former Olympic artistic swimmer

International meets include solo competition — strange for something formerly known as synchronized — and duets. The more common team event has eight swimmers performing shoulder-to-shoulder, executing each move with the timing of a Rockettes routine. Coordination is essential when everyone ducks underwater to form a human pyramid for “lifts.”

The strongest swimmers, known as “pushers,” create a foundation but cannot, under any circumstances, touch the bottom of the pool. The middle layer is called the “base” and then come the “flyers” on top, one or two small athletes who get heaved out of the water, high enough to execute twists and flips before splashing down.

“I like being a flyer,” the 5-foot-5 Ramirez says. “Yeah, I get to breathe.”

As in figure skating, competitions include two routines. The technical phase lasts about three minutes with swimmers performing required elements such as the ballet leg, fishtail full twist and barracuda airborne split. The free routine is longer at about five minutes, emphasizing artistic impression and degree of difficulty.

Ten judges sit poolside, watching from different angles, marking deductions for anything misaligned or off-tempo. They factor musical selection into their scoring and pools have underwater speakers so swimmers can stay in rhythm while submerged.

“Things have evolved very much since my time — it’s more acrobatic, more athletic,” says Nicole Hoevertsz, an International Olympic Committee official who competed for Aruba at those 1984 Los Angeles Games. “You need eight to 10 hours a day, year-in and year-out, to become a good artistic swimmer.”

The first question artistic swimmers get asked is always the same: How long can you hold your breath?

“We don’t do it all at once,” national team member Jaime Czarkowski says. “If the routine is three minutes, we go 17 seconds underwater, then 15 seconds above, then 17 seconds under again. It’s a lot of up and down.”

Still, seconds can feel like minutes as the heart beats faster, all that up-and-down threatening to trigger what experts call “shallow water blackout.”

The problem is, gasping for air with each resurface expels too much carbon dioxide, disrupting the balance with oxygen and tricking the brain into thinking there’s no need to breathe. A 1961 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. found that, prior to blacking out, swimmers recalled believing they could go forever. Though it is unclear if Alvarez suffered an episode of shallow water blackout, she remembers having a “great” performance before blacking out at the world championships.

“That’s the insidious thing,” says Tom Griffiths, founder of the Aquatic Safety Research Group. “Just like marathon runners experience a runner’s high, breath-holders get the same high.”

After loss of consciousness, carbon dioxide levels rebound abruptly, causing the passed-out swimmer to involuntarily inhale water, which disrupts body chemistry and can stop the heart. At that point, Griffiths says, survival becomes “a crap shoot.”

The U.S. team undergoes breath-control training and reviews warning signs — tingling, muscle cramps — that can precede a blackout. Still, experts worry. “Synchronized swimming is a wonderful sport but there are some inherent dangers any time you hold your breath underwater for a long period of time,” Griffiths says. “This happens to good athletes, people who really push themselves.”

Therein lies a quandary.

Like coaches in other sports, Fuentes trains athletes to “forget about the physical sensations that are not pleasant ones … instead of listening to the physical tiredness or exhaustion, it’s about how to be better.” Like other elite athletes, artistic swimmers develop a high tolerance for discomfort.

Synchronized swimming has long been lampooned, but artistic swimmers argue it requires great stamina, endurance and strength to win gold.

“People finish a marathon and pass out,” Vega says. “I mean, it’s just one of those things that happen.”

But when runners or cyclists or weightlifters compete to the point of exhaustion, and beyond, they don’t risk drowning.

After the world championships, as Alvarez underwent one medical test after another, her teammates returned to practice at UCLA. With their veteran leader and two-time Olympian absent, they talked about the sport.

Some had been freestylers or backstrokers who grew bored of swimming in straight lines. Others were gymnasts drawn to the water. Fuentes, who competed in three Olympics for Spain before coaching, mentioned something else.

“I love the artistic things,” she says. “You can express, in an artistic way, everything you can imagine.”

Still bound to its theatrical origins, artistic swimming is about telling stories through athleticism and movement. Swimmers take classes in ballet and modern dance, even improv comedy, anything to help sell the judges.

This season, with the Americans performing a technical routine to the pop hit “Smooth Criminal,” coaches arranged a trip to Las Vegas for a workshop with the cast of Cirque du Soleil’s “Michael Jackson One.” It was a chance to learn about the late singer’s dance moves and hand gestures, even the famous lip bite.

“All they do is study Michael Jackson,” Ramirez says. “They gave us a rundown, the pointers on what we need to do and what we need to portray and the messages he wants to put out through dance.”

At a recent practice, Fuentes asks for a signature Jackson move, head back, shoulders forward. One of the swimmers grumbles: “My neck is already sore.”

Facial expressions also play a role in conveying emotion, which explains all the mascara and blush because judges need to distinguish a smile from a frown from 30 feet away.

Lipstick and eyeshadow should match the costumes. Sparkle can be a nice touch. It should be no surprise that the U.S. national team is sponsored by a company that makes compacts and vanity mirrors.

“My makeup skills were not that good when I was younger,” says team member Elizabeth Davidson.

The ideal of homogenous beauty, everyone trying to look perfect or, as one swimmer put it, “matchy-matchy,” has its dark side. The sport has seen incidents of mental abuse, including fat shaming, by coaches and a recent UCLA study found significant rates of depression among U.S. team members dating back 30 years.

Current athletes say Fuentes, who took over in 2018, never badgers or belittles. She was the one who dove into the pool, fully clothed, swimming to the bottom, to save Alvarez. The young coach likes to think of herself as part of a new generation, guiding a squad that includes diverse ethnicities and body types.

Still, the sport demands not only copious makeup but also hairdos plastered down in a curious way. Swimmers must heat a pot of unflavored gelatin, the goopy stuff normally used to thicken broths and puddings. When brushed into the scalp, it hardens to a glistening shell that lasts all day, if not longer.

“You need a lot of hot water and combing to get it out,” Davidson says. “If you don’t get it all, it’s ripping out chunks of your hair.”

No one uses hair gelatin for morning practice; swim caps suffice. Instead of cosmetics, team members slather their faces with white zinc oxide to protect against the morning sun. Alvarez is among the first into the pool.

Medical tests have yet to determine why she passed out last summer, or once before at a 2021 competition. “It’s been hard to deal with all the doctors’ appointments, just to be constantly thinking about it,” she says. “We need to figure this out.” For now, she can resume training.

The team begins with “verticals,” everyone flipping upside-down on command, straightening their legs into the air. Assistant coach Hiea-Yoon Kang paces along the edge, talking into the microphone, calling out imperfections.

“You need to squeeze your left shoulder,” she says. “Left side forward.”

Words don’t always suffice as coaches contort their bodies to demonstrate proper form and swimmers speak in a rhythmic sort of language. “Do you want bop-bop-bop?” Davidson asks. “Or bop and then bop?”

Clean lines and tight formations above water belie something very different below. Hip and knee injuries are common because, as Alvarez explains, there are so many “legs working and people kicking each other. It’s madness under there.”

The physical nature of artistic swimming is nothing new to her; less familiar is the fear that occasionally bubbles up underwater since the blackout. Alvarez refuses to be deterred.

Stubbornness — the memory of what happened — accounts for part of her determination. “How could I want that to be my last competition ever?” she asks. Just as important is something that originally drew her to the sport, something outsiders don’t always see, a challenge that can be addictive.

“You’re always striving for perfection, which is impossible,” she says. “There’s always more to do.”

As practice stretches past midday, the U.S. team works on a difficult lift. Time and again, they are off-kilter or ill-timed. With a key role at the pyramid’s center, Alvarez takes a few minutes to practice on dry land, coiling her body, springing up and extending her arms.

The veteran dives back in for another try. Taking her place in the formation, ducking under, she remains submerged for long seconds before rising suddenly and giving a stiff push, hurling a flyer skyward.