Column: How Peter Ueberroth saved the Olympics and revolutionized the Games

The assembled guests were eager to hear Peter Ueberroth’s words of wisdom, hoping he’d extend a pleasant hour of reminiscing about the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics to tell stories about the vision he’d conceived and executed to make the Games so profitable, inclusive and entertaining that they’ve remained an unattainable standard for every Summer Olympics that has followed.

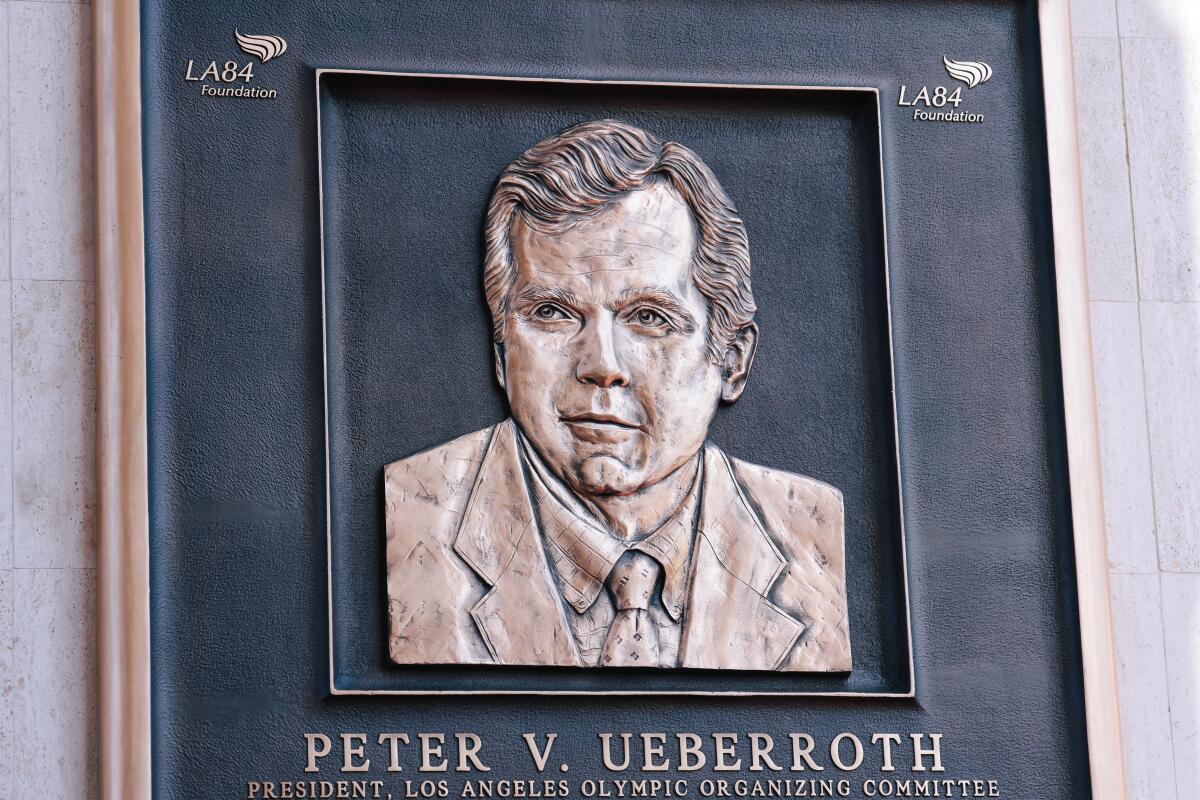

Standing in tribute as Ueberroth stood at a stage set up near the Coliseum’s Court of Honor — where a plaque with his likeness was one twitch of cloth away from being unveiled to the world — his friends, family, and admirers prepared to take their seats to savor his speech. Don’t sit, the former chairman of the L.A. Olympic Organizing Committee cautioned them.

“I just want to thank everybody,” he said. “You heard a lot of nice comments. Some of them were true, some of them were exaggerated, but the fact is in this society that we all live in, everybody that I can see and everybody behind us or in front of us, we can make a difference. And we can all make a difference. And God bless you all.”

He spoke for less than a minute. At 85, he’s still very much a man of action, not words, more inclined to look toward the possibilities of the future than waste time recounting what he did decades ago, even if those feats have become part of the fabric of life in Los Angeles and part of Olympic history.

If there’s anyone entitled to give long-winded speeches and brag about the great things he has done, it’s Ueberroth. Successful businessman. Baseball commissioner. Chairman of the U.S. Olympic Committee. The man who saved the Olympics — and that’s no exaggeration.

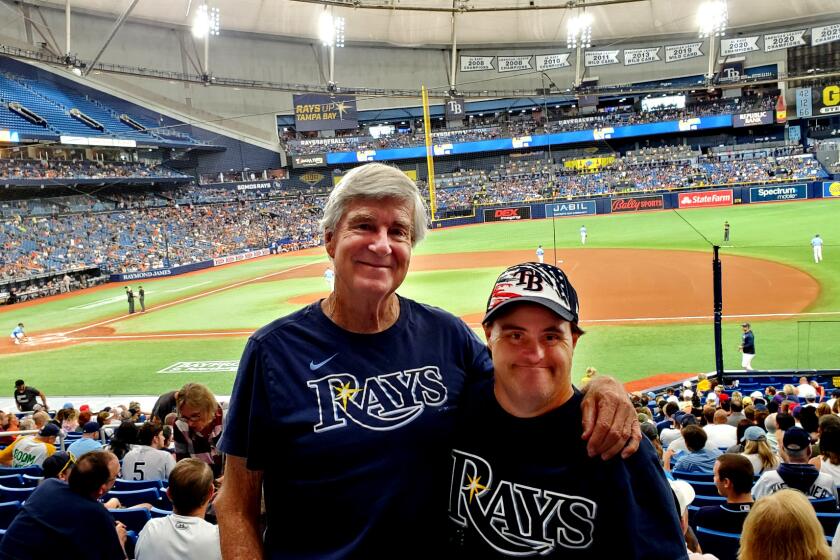

My son is 53. He’s a baseball fan. He has Down syndrome. To him, baseball is more than a game.

“I think that’s a true statement, to be honest with you,” said Mark Spitz, almost unnoticed in street clothes and without those nine Olympic swimming gold medals arrayed around his neck. “He created a financial model they’re desperately trying to emulate.”

The Olympic movement was faltering badly in the 1980s. The terrorist attack that killed 11 Israelis at Munich in 1972 was tragic and shocking. Montreal took on so much debt to stage the 1976 Summer Games that the bills lingered for three decades. Then-president Jimmy Carter ordered a boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Nobody but Tehran, Iran, and Los Angeles bid for the 1984 Games.

Ueberroth, supported by then-mayor Tom Bradley, created a private financing plan that relied on media rights and corporations. The Games were commercialized as never before, yes. They also turned a profit of about $225 million, some of which went to the U.S. Olympic Endowment for athletes’ use and some back to Los Angeles to what’s now the LA84 Foundation, a nonprofit that helps give kids sports equipment, facilities and coaching.

“Without Peter Ueberroth, without the ’84 Games being as successful as they were, I believe it’s very likely that the Games could have sputtered and, like a match, gone out,” said John Naber, a five-time Olympic swimming medalist. “He added the fuel and the flame, and he increased the stakeholders.”

A happily large group of former L.A. Olympic committee staffers attended the long-overdue ceremony at the Coliseum on Monday and posed for pictures with Ueberroth and his wife Ginny. Ueberroth’s plaque was placed across from Bradley’s and near that of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who’s considered the father of the modern Olympics. Perfect placement. DeCoubertin brought the Games back to life. Ueberroth ensured they’d continue for generations.

“You gave us a new narrative for our city and for our world when we needed it most,” said mayor Eric Garcetti, who joked that his second action as mayor — after paving a street to prove his commitment to city services — was to inquire about hosting the 2024 Summer Games. That bid wasn’t successful, but L.A. will get a third turn as host in 2028.

“This is a city not just of dreamers but of doers,” Garcetti said. “It’s wonderful that you had a dream, Peter. But I think what we recognize is that you were able to bring a team together to enact that dream.”

Ueberroth’s Games expanded opportunities for women, with events including the first women’s Olympic marathon, and for disabled athletes. L.A. 84 was the first Games to include wheelchair racing exhibitions, a milestone moment that spurred the growth of the Paralympics.

“The negative bias and stigmas that surrounded disabled people at that time were peeled back on that day,” said Candace Cable, a bronze medalist in the women’s 800-meter wheelchair race. “Those few minutes in the worldwide broadcast took us from discarded, dehumanized disabled people out of the dark shadows of worthlessness and brought us into the bright light of truth, that we are all human beings with value and deserve access and inclusion to all that life has to offer. Using sport for inclusion and access messaging was perfection.”

If the Kings want to become serious Stanley Cup contenders, they will need someone to match or exceed Anze Kopitar’s scoring totals.

Short as his speech was, maybe Ueberroth said all he needed to say. “I wanted to tell the truth. It takes a few hundred people to make a difference and they did, and I was one of them,” he said.

“I’m just proud of the quality of people in this community and in this country so I’m thrilled with that. The rest, that’s in the past. And we live in the present and future. So, I’m looking forward to the future.”

That includes rooting for the success of the 2028 Olympics.

“The people that are running those Games, they’re darned good. They’re going to surprise the world how great those Games will be,” he said. “The Olympic movement is now pretty darned strong. The [2028] people are sensational and a lot of them have experience with our Games and so they’re going to be terrific.”

He will be just short of 91 when the Olympics return to Los Angeles. But save him a seat.

“Yeah, for sure,” he said.

Just don’t expect him to make a long speech.