Why no U.S. Olympic handball teams? Sport hopes L.A. 2028 will spur resurgence

TOKYO — It’s become a Summer Olympics tradition: Americans turn on their televisions to watch the Games and find a sport they don’t quite understand but know, just know, that the United States should easily dominate.

They’re baffled once they realize that the U.S. — men and women — again didn’t even qualify for a game they swear they played in gym class. They can’t fathom why the United States of America — boasting more elite athletes in team ball sports than any other nation on Earth — is so behind in team handball.

“I’ve heard it for about 50 years,” Dennis Berkholtz said with a laugh.

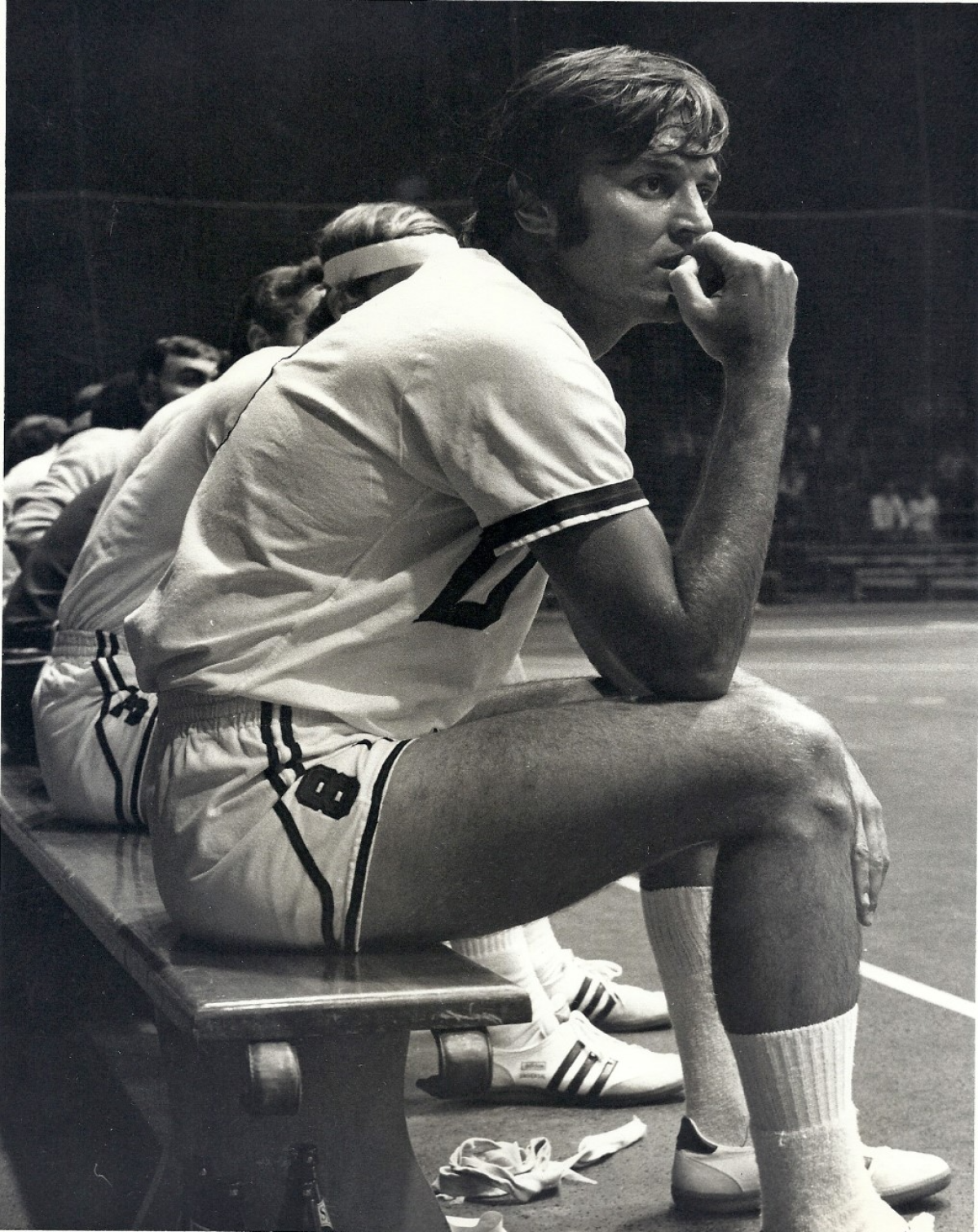

Berkholtz, 76, is an American handball pioneer. He was the U.S. men’s team captain for handball’s Olympic debut at the 1972 Munich Games, coached the men’s team four years later in Montreal, and served as USA Team Handball president from 1996 to 2000. Every step of the way, Berkholtz tried to awaken the supposed sleeping handball giant. Every time, the slumber continued.

Breanna Stewart is playing in her second Olympics. She hopes to play in at least three more, like fellow Team USA members Diana Taurasi and Sue Bird.

Apparently, transforming the U.S. into a world handball juggernaut isn’t as easy as everyone watching every four — in this case five — years thinks. The abbreviated reason for the failure is an endless cycle that leads back, as always, to money. More participation produces more success, which generates more revenue, which supplies the necessary funding, but there has never been enough participation to initiate the sequence.

Hope isn’t lost. Those leading the charge believe, with an overhauled approach, that the U.S. men’s and women’s teams can be competitive at the 2028 Los Angeles Games, where they’ll automatically qualify as the host country.

“There’s almost unlimited potential,” said Ryan Johnson, USA Team Handball chief executive. “And once we get a little bit of momentum, I think it’s really going to catch fire.”

Team handball resembles a combination of basketball, baseball, football, lacrosse, and water polo played on hardwood. Each team deploys seven players — six field players and a goalkeeper — on a court just bigger than a basketball floor. There are two 30-minute halves. Teams are given one 60-second timeout a half. Otherwise, the clock doesn’t stop. Substitutions are made on the fly. The ball is few inches smaller than a volleyball and built like a soccer ball.

Players can take up to three steps before they must dribble, pass or shoot. To score, a player throws the ball from outside the six-meter arc outlining the goal area. Players can jump into the goal area, but they must shoot the ball before landing. Each goal counts as one point.

Contact is permitted but players aren’t allowed to stretch their arms or legs to obstruct, push, hold, trip or hit opponents. They can’t hit, pull or punch the ball out of an opponent’s hand. Offensive players can’t charge into or purposely throw the ball at defenders. Kicks are illegal. Penalty throws from the seven-meter penalty mark are awarded when a referee rules that a defender illegally impeded a scoring opportunity.

The first official team handball match was played in Germany in 1917. Over the years, the sport became popular across Europe, and in parts of South America and the Middle East. The game didn’t formally reach the U.S. for decades.

Berkholtz played basketball at Kansas State before he joined the Army. In 1969, while serving, he was chosen as part of the first group of Americans to train for competitive handball with eyes on the 1972 Games He is, as he put it, the first good athlete in the U.S. to learn to play the sport. He fell in love.

“I’ve played all the sports, as do most of the American guys that play handball,” Berkholtz said, “and every single one of them would tell you it’s the best sport we’ve ever played.”

Yoyogi National Gymnasium has been the center of the handball world for the last two weeks. Teams from 18 countries were represented at the men’s and women’s Olympic tournaments. There isn’t one — in either field — from North America.

The games are fast paced, the scoring nonstop. Thuds off the hardwood floor accent the sprints, jumps and throws.

Tempers briefly flared in the Tuesday’s men’s quarterfinal game between Spain and Sweden — third- and second-place finishers at January’s world championships — before the Spaniards erased a four-goal deficit with 15 minutes remaining to seal a spot in the semifinals against Denmark, the reigning Olympic gold medalists.

“We’re way behind a really fast running train. So we’ve got to pick up speed but we’ve also got a lot of catchup to do.”

— Ryan Johnson, USA Team Handball CEO

They spontaneously celebrated when the buzzer sounded for their 34-33 win. The Swedes, devastated, formed a circle for one final huddle and sulked off the court.

The loss was big news back in Sweden, a country steeped in handball tradition. The Swedes have won four world championships, tied with France for the most since the competition was introduced in 1938. They finished second — one spot ahead of Spain — at this year’s championships in January.

Players from those two countries and others populate high-profile domestic leagues — Germany’s Bundesliga is regarded as the best — and the European Handball Federation’s Champions League. Top players’ salaries reach seven digits. Denmark’s Mikkel Hansen, a three-time world player of the year, has a reported net worth of $44 million. Internationally, team handball was the second-most ticketed sport at the 2016 Rio Games.

The U.S. is light years behind, without even a structured youth program. While European players learn the game young and are developed in elaborate academies, the U.S. teams’ current best hope is to convince athletes from other sports to pick up handball.

Ty Reed made the switch. He walked on to Alabama’s football team — first as a quarterback then as a wide receiver — and in 2015 joined U.S. handball’s one-year residency program, the primary feeder unit for the national team. He worked out five days a week and made his international debut in Uruguay after four months, eventually becoming a professional player in Europe.

“American handball, it’s not even close to what European handball is,” Reed, 29, said. “So even though were learn in the States, there’s nothing that’s comparable to that. I guess you can learn the rules of the game but it’s like playing pickup basketball compared to NBA basketball.”

And the U.S. going up against world handball powers often looks like the overmatched countries smashed by the 1992 Dream Team.

U.S. pitchers Joe Ryan and Scott Kazmir are big fans of the baseballs being used in the Tokyo Olympics. Would MLB consider making a switch?

Randy Dean might be the most accomplished American male athlete to ever play handball at a high level. He played basketball and football at Northwestern and spent four NFL seasons as a backup quarterback. He made the 1976 U.S. Olympic handball team. The Americans went 0-4 and placed 10th out of 11 teams.

Phoenix Suns center Frank Kaminsky has said he wants to play the sport, but he hasn’t taken the plunge. In 2020, retired NFL quarterback Jay Cutler said he could put together a team that would win an Olympic gold medal. NBA All-Star Luka Doncic, who grew up playing handball in Slovenia, tweeted a rebuttal: “No chance!”

“The handball community is small, but they’re driven,” Reed said. “They’ve been tweeting Jay Cutler every day since he’s been saying that. In all fairness, he’d get destroyed.”

Said Berkholtz: “Take it from somebody who’s played a lot, seen a lot, I got a lot of friends in Europe. They laugh when they hear that. ‘Oh, bring [Michael] Jordan over here and we’ll knock the [expletive] out of him.’”

The problem, Berkholtz insisted, is that it would take athletes from other sports years of training to compete at a high level, and there isn’t enough money available to keep them around. Having high-level athletes make the leap could drive interest, which could generate money and turn the tide, but that hasn’t materialized. Instead, even lower-tier athletes aren’t incentivized to stick with the program.

“What happens is when the good athletes play — men and women — they train for two years or a year and a half, they go to the Games, they come home, they go get married, get a job, and they don’t play anymore,” Berkholtz said. “So each cycle, we have to start over again.”

It’s Johnson’s job, as USA Team Handball chief executive, to harness the interest generated at every Olympics when Americans pay attention to the sport and channel it toward more members, events, and programming.

To do that, Johnson said his organization is working to create a better system to transition second-tier athletes to the sport with collegiate clubs. The long-term goal is to attract even younger players and create youth programs to sustain participation. Johnson said the organization could have an easier time attracting women since there are fewer high-paying options in women’s sports.

“We’re way behind a really fast running train,” Johnson said. “So we’ve got to pick up speed, but we’ve also got a lot of catchup to do.”

Berkholtz said he believes the first focus should be developing the sport in one place. He suggested California with Los Angeles as the focal point and finding “sugar daddies” for funding.

“You go to the tech guys, and you say, ‘Hey, we need some help. You can be the father of this sport for the next eight years,’” Berkholtz said. “And they become like team owners of the Olympic team.”

For now, the men’s team comprises mostly Europeans with dual citizenships and a few American-born players. Soon it will include 16-year-old Tristan Morowski, a 6-foot-5 left-hander born in New York to Polish parents who plays for an academy in Germany. The teenager is considered the future of the sport in the United States. He’s the prototype for the 2028 Games and beyond.

“It’s not going to be so much about the wins and losses in L.A.,” Johnson said, “but how relevant is our team in 2029 and 2031 and in 2032.”

Maybe, finally, Americans will turn on their televisions to find the U.S. competing with the world’s best by then, ending the decades-long quadrennial confusion. It won’t be as easy as it looks.