CULIACÁN, Mexico — Carlos Urías has a routine before watching every one of his son’s starts: He plugs in a Virgen de Guadalupe light fixture hanging in the hallway just off the living room and prays.

La Virgen was bright on a recent Sunday morning, colorfully illuminating the dim white space. A few minutes after 10, before Julio Urías took the mound 2,000 miles away in Miami, Carlos approached her. He took off his Dodgers cap, whispered some words and offered the sign of the cross.

“God has been good,” he said. “I have a lot to be thankful for up there.”

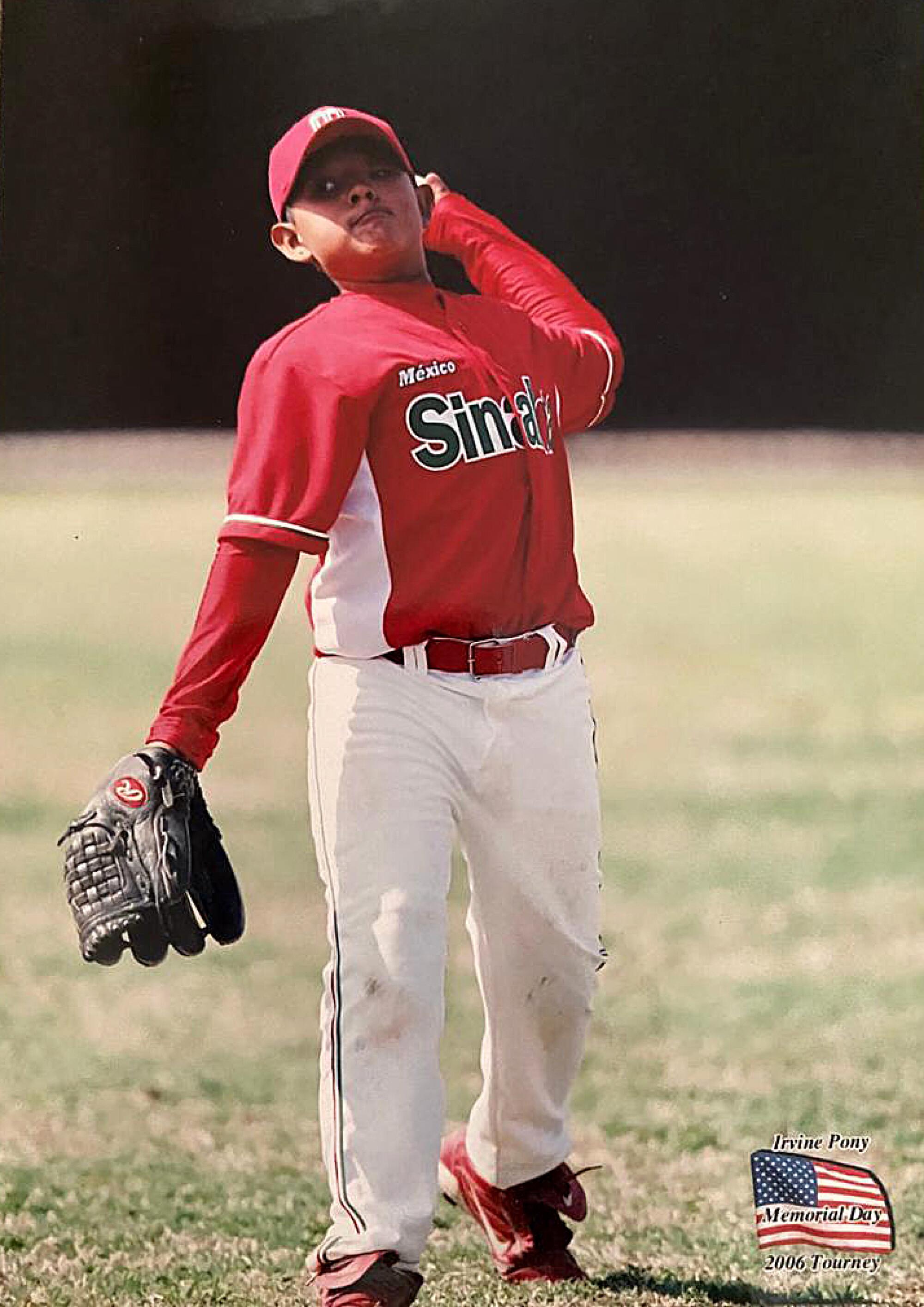

Julio César Urías hasn’t spent a summer here in a decade. Not since the boy with the bad left eye and gifted left arm signed with the Dodgers to continue a life already with more bright moments and dark days than most of his peers will ever experience.

The 26-year-old left-hander is a former hotshot prospect who made his big league debut as a teenager, struggled to find his footing with the Dodgers, underwent major shoulder surgery, served a 20-game suspension after being arrested on suspicion of domestic violence, and returned to fulfill the outsized on-field expectations that originally awaited him.

He’s the ace on a team with the best record in the majors and World Series-or-bust ethos, starring in Los Angeles as the most beloved Mexican Dodger since Fernando Valenzuela.

“Patience has been fundamental for my career,” Julio said. “Being patient and not worrying about when my moment is coming.”

The foundation was shaped in this growing city of nearly 1 million people on Mexico’s Pacific coast universally associated with drug cartel violence, and in a community called La Higuerita 10 minutes from Culiacán’s urban cluster.

It’s where Julio grew up, first in his grandparents’ house until there was enough money for his family to move into its own home when he was 13.

It’s where he was bullied for an eye that wouldn’t stay open and where his father firmly demanded excellence on the baseball field. It’s where he was celebrated for his uncommon athletic exploits as a boy and where he spends the holidays during the offseason as a man, drawing crowds everywhere he appears in public.

Julio Urías has been on a tear for the Dodgers, and his strong performance Saturday was among the decisive factors in an 8-4 win over the Padres.

It’s where he plans to conclude his career, pitching for the Tomateros de Culiacán in the Mexican winter league, and to invest some of his earnings. It’s where he wants to help the people whenever possible. It’s where his family will remain.

“I’ve been here my whole life,” Carlos said, “and I’m going to die here.”

The Urías family gathers in their living room to watch Julio’s starts, inviting relatives and friends, whenever possible. For this outing against the Miami Marlins, Julio’s parents, Carlos and Juana Isabel Acosta, are joined by his brother Carlos Jr. and his grandparents.

As more relatives and friends arrived, Carlos and Carlos Jr. focused on every pitch as the surrounding bustle amplified.

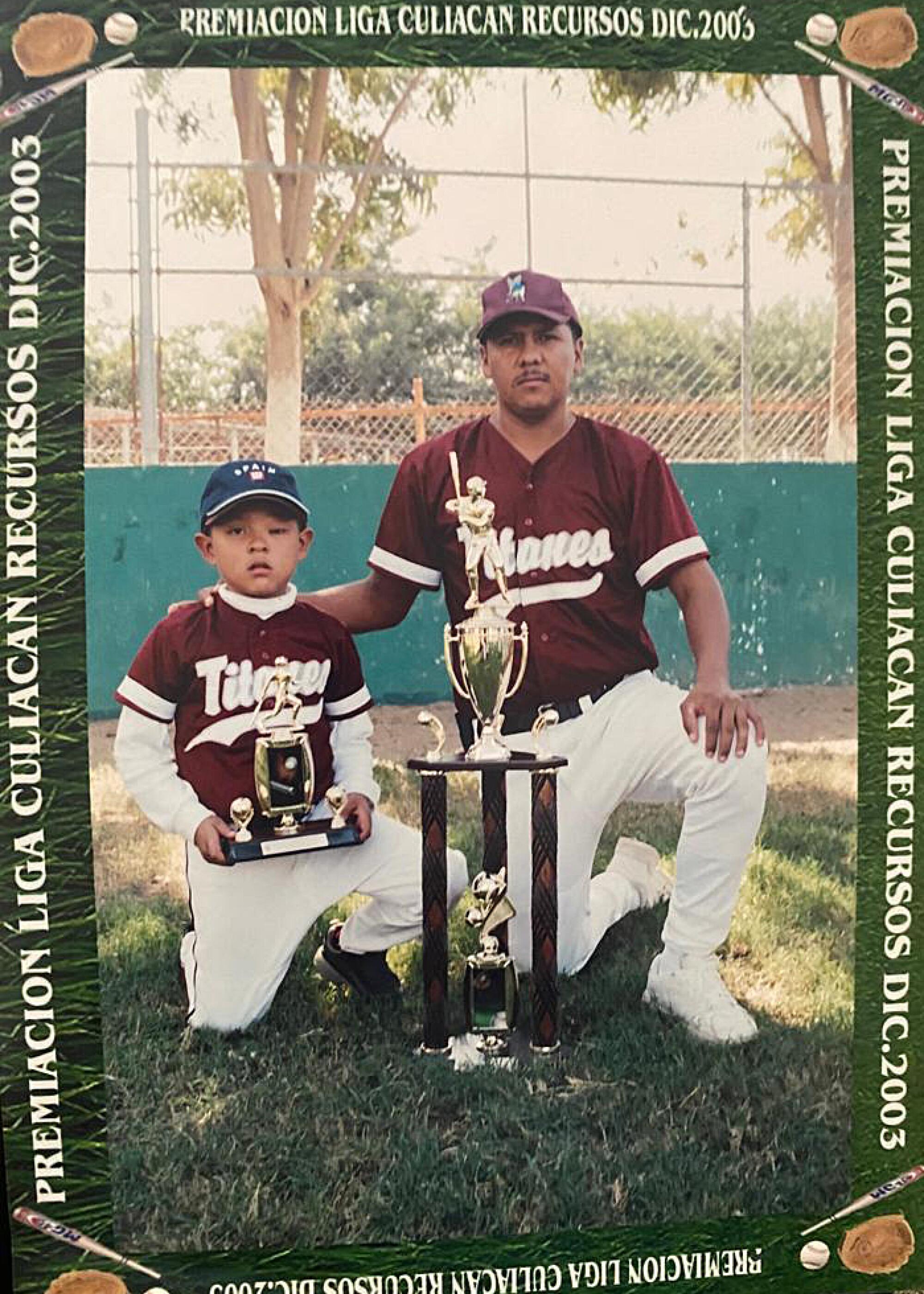

“It’s every father’s dream to see their son in the big leagues,” Carlos said.

Carlos, 50, was a semi-pro baseball player into his 30s.

“I tried,” he said.

Julio’s slurve, a pitch he unveiled during his breakout 2020 season, was sharp as he plowed through three hitless innings. Then, in the fourth, he left a fastball over the plate to Brian Anderson. Julio didn’t bother to see where it landed over the wall, yelling at himself for the mistake. It was the only hit he surrendered in six innings.

“He’s not afraid,” Carlos Jr., 20, said. “He’s only afraid of heights.”

Julio’s life began with fear. Dread swamped Carlos and Juana the moment they realized their first-born child had an eye problem. Doctors initially couldn’t identify the issue until they diagnosed Julio with a tumor when he was 4. Tests found it was benign, but doctors told the family the tumor would aggressively grow through his teenage years and removing it would risk compromising Julio’s eye.

“I think all of that made my son strong.”

— Carlos Urías on son Julio undergoing eye surgery 10 times before age 10

Repeated, less invasive, surgeries would be required to keep the eye open. The stress prompted the couple to wait to have another child. Six years later, Carlos Jr. was born.

“The first thing we did when Carlos was born,” Carlos said, “was look at his eyes.”

Julio’s grandfather owned the nine-person household’s only car, so Julio and his father would take a 12-hour bus ride to Guadalajara for surgeries whenever the eye was sealing shut. Doctors tied his hands down after surgery so he wouldn’t remove the patch or the IV in his arm. He was prescribed medication to hinder the tumor’s growth. Carlos estimated Julio underwent 10 surgeries by the time he was 10.

“I think all of that made my son strong,” Carlos said.

The rides were usually overnight unless they stayed with the only relative they had in Guadalajara because they couldn’t afford a hotel. Eventually, they started taking eight-hour bus rides up the coast to Ciudad Obregón for the procedures.

Once, when Julio was about 9, two passengers robbed everyone on the bus at gunpoint. Nobody was hurt.

“Thank God we didn’t have anything,” Julio said with a chuckle, “so they didn’t take anything.”

Children taunted him at school. They called him tuerto and bizco; one-eyed and cross-eyed. They nicknamed him “four eyes” when he wore glasses. The operations would leave him with a black eye, and children quipped he must’ve been beaten.

His parents pleaded with him to not fight back when others cracked jokes, worried that a blow could ruin the eye. For a few years, at a doctor’s urging, they convinced him to wear a patch over his right eye Monday through Friday for a month at a time to make sure he kept his left one open. He protested. He promised to not close his bad eye. He cried. Carlos and Juana refused to relent.

“He would ask, ‘Why am I different?’ ” Juana said. “I always told him, ‘You’re not different.’ ”

“I don’t look at it as bad because it doesn’t impede me from anything. I do everything normal like anyone else. That’s how I look at it.”

— Julio Urías on the eye issues he has endured since childhood

There was one place Julio didn’t mind being different: for a few hours Sunday on a baseball field, where he was better than everyone else.

He knew he needed vision in both eyes to play. It’s what his parents used to encourage him to withstand the name-calling, to endure the long bus rides, to wear the patch. He wanted to play baseball.

“It affected me a bit mentally because I looked in the mirror and I didn’t want to see me like that,” Julio said. “But, little by little, I came around to understanding and learning, so I think I took out the most positive, and the most positive I feel was this sport.”

Julio overcame his first challenge as a baseball player in his grandparents’ front yard.

His father built a pitcher’s mound in one corner. In another, his grandfather Julián crouched as the catcher and Carlos posed as the hitter. When Carlos noticed Julio was afraid to pitch inside, he started standing with a glove. He begged Julio to not worry about plunking him because he would catch the ball. Julio laughed when his father snatched his first misfires. The anxiety dissipated.

“That gave me the confidence,” Julio said.

He dominated the local youth league at every level — as a pitcher and a hitter. He wore No. 7 because his favorite Tomateros player, Darrell Sherman, a star outfielder from Los Angeles, wore the number. He threw changeups by the time he was 7. He smashed jaw-dropping home runs.

“My son was younger than Julio so he would play on the field next to his,” said Carlos Rubio, a local businessman who owns a Dodgers-themed barbershop in the city. “And every time Julio was pitching or hitting, I had to watch. He was a phenom.”

Julio’s dominance earned him spots on national teams, and he represented Mexico in international tournaments in Central America, South America and United States.

“In our 9- and-10-year-old league, they would only let you pitch four innings,” recalled Fidel Alba, Julio’s youth league catcher. “And he wouldn’t allow a hit every time. He would strike out 11 or all 12 batters. And then he would hit two or three home runs a game. As a kid you don’t realize how good he is, but everyone in Mexico knew who Julio Urías was.”

Carlos coached his son’s teams from the time he was 6 until he became a professional. He expected perfection. Julio rarely struggled, but if he did — gave up hits or threw pitches his father didn’t like — Carlos scolded him in front of his teammates and ignored him for days. Julio viewed his father as a “military man, like a general.”

Years later, the subject was broached between father and son over drinks.

“He told me, ‘When you have your children, you do what you want, but I did it that way and look where you are,’ ” Julio said. “He has a point. There isn’t a book on how to raise a child. He has his reason. It was the best for me because it showed me if I’m going to do something, I have to do it right.”

Julio’s development didn’t wane leading into the summer of 2012. But when it came time to negotiate with major league clubs, Carlos said, teams backed off believing his eye would be a problem. Carlos told teams he had one demand: that Julio be sent straight to the minors in the U.S., not to the Dominican Summer League.

The Dodgers eventually gave the Diablos Rojos del Mexico, the team that owned Julio’s rights in the Mexican League, $1.8 million for Julio and three other players. Julio officially signed on Aug. 12, his 16th birthday.

The left-hander spent his first full professional season in 2013 pitching for low-A Great Lakes where he was nearly six years younger than the league’s average player. Two years later, while pitching for double-A Tulsa, he underwent another eye surgery. He was back on the mound in two months. He hasn’t had an eye operation since.

“Those are the types of things you can call bad, but I don’t look at it as bad because it doesn’t impede me from anything,” Julio said. “I do everything normal like anyone else. That’s how I look at it.”

One year after the procedure, Carlos received what felt like a random call from his son. Julio asked if there was anyone around. Carlos was at work, coaching children, when Julio said he had news. He was being called up to the majors. They cried.

Carlos rushed home. He and Juana went to La Lomita, to the prominent church overlooking the city atop a hill, with a bouquet of flowers. A family friend surprised the family — Carlos, Juana, Carlos Jr. and sister, Alexia — with plane tickets to New York the next morning to watch Julio pitch against Jacob deGrom and the Mets.

Julio bounced between the majors and minors the rest of the season, posting a 3.39 ERA in 15 starts and three relief appearances. He pitched in two playoff games, but the Dodgers had him open the next season in extended spring training hoping to alleviate his workload. The decision irked him.

“That doesn’t happen with a lot of players,” Urías said. “But you have to understand they’re doing it for a reason.”

The next June, he underwent season-ending shoulder surgery, the type of setback Julio had never experienced in his baseball life. He returned to the Dodgers 15 months later, in September 2018, as a reliever and made the postseason roster.

He rode the momentum into 2019 in a hybrid role between the rotation and bullpen. Then his progress came to a halt. He was arrested on suspicion of domestic battery on May 13 after witnesses told Los Angeles police they saw him push a woman to the ground in a parking lot.

Urías and the woman denied the incident was more than a verbal altercation, but authorities reviewed surveillance footage and ruled the woman had been pushed.

Major League Baseball put Urías on paid administrative leave the next day. He was reinstated after seven days and made his next pitching appearance on May 25.

Two weeks later, Los Angeles city prosecutors announced they wouldn’t file misdemeanor charges if Urías was not arrested again for violent behavior over the next year and completed a yearlong domestic violence counseling program in person.

In August, Urías accepted a 20-game suspension. He returned in September for the rest of the season.

“It was difficult,” he said. “I don’t even like to talk about it or remember it because they’re very complicated moments in life that you don’t want to see yourself or another person in that situation. … It was a lesson and I feel like if I have a stain, it’s that one.”

The Urías family house originally had two bedrooms and a bathroom inside. The kitchen and dining room were outside on a dirt floor. Julio shared a bedroom with his parents and two siblings — the other bedroom was filled with supplies for the neighborhood’s plumbing system — until he left for the minor leagues.

They soon added a dining room, kitchen, and living room inside. A second floor was constructed after Julio received his signing bonus.

Upstairs is where Julio’s memorabilia and keepsakes reside. The ball from his major league debut. The ball from his first save. The ball from his first World Series appearance. A Guinness Book of World Records that includes Julio for being the youngest player to start a major league postseason game.

The family could afford a bigger, more luxurious space, but this is home.

Everyone in Culiacán understands the city’s reputation. The capital of Sinaloa had one of the top 25 homicide rates in the world in 2019. Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the notorious drug cartel leader, is from a rural community nearby. Narcotrafficking is part of the economy.

Residents, Culichis, insist Culiacán isn’t the place you see on television. They say it’s a place with problems and positives like anywhere else.

They point to the widespread construction, a sign of a city outgrowing its backwoods stereotype. They proudly talk about their food — the barbacoa, the chilorio, and, above all, the mariscos. They share a love for banda music and their celebrated brand of sushi, a breaded twist on the Japanese staple filled with Philadelphia cream cheese. There are people going to school and working hard and living ordinary lives.

Unlike most other places in Mexico, baseball, not soccer, is the prevalent local sport. There’s a professional soccer team — Diego Maradona served as manager for two seasons — but this is a Tomateros town.

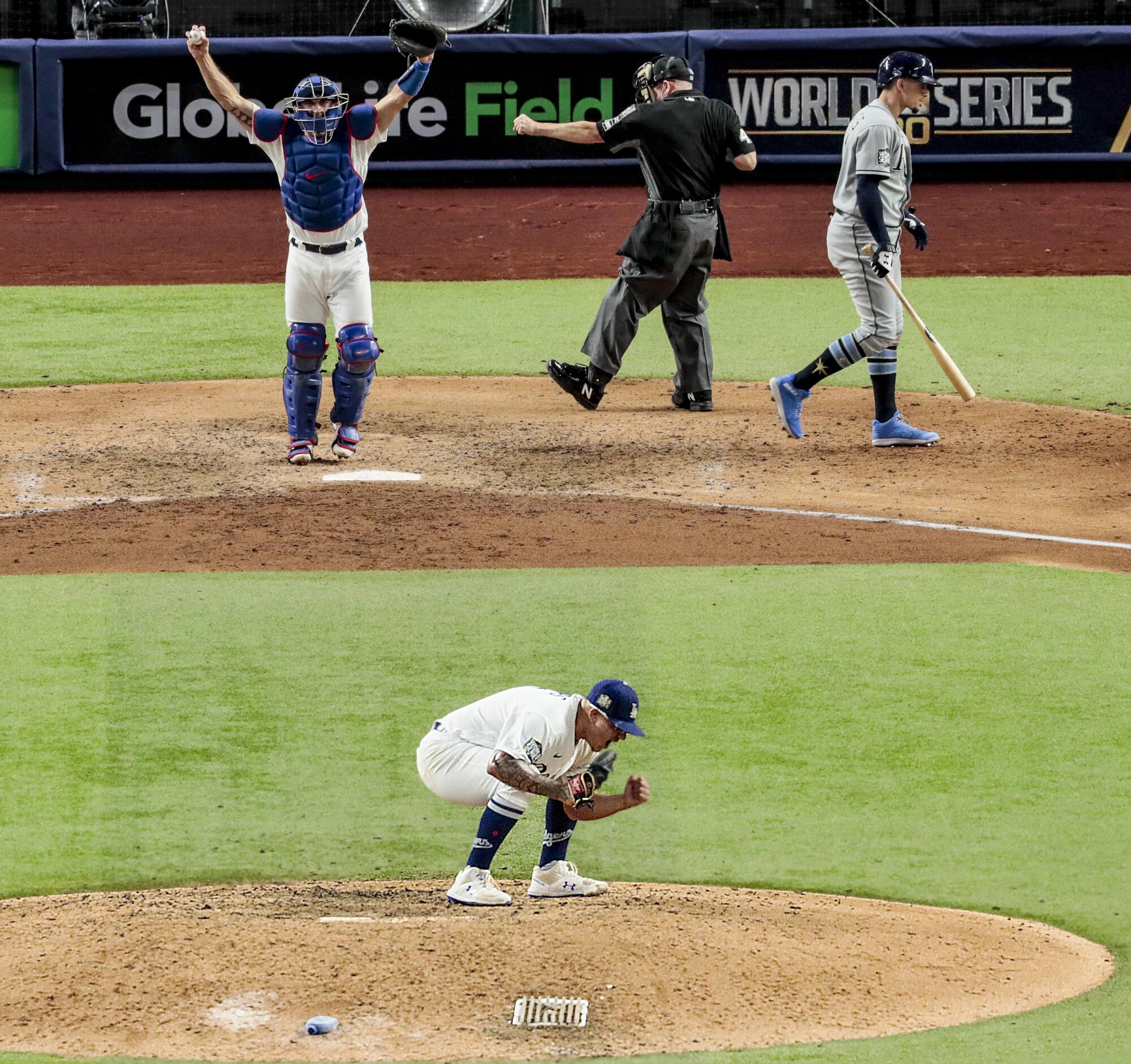

The city, like the rest of the world, shut down in 2020. Julio, meanwhile, seized a shortened 60-game season to establish himself as an indispensable piece in the Dodgers’ machine that went on to win the World Series by beating the Tampa Bay Rays in six games.

Julio was on the mound for the ending, striking out Willy Adames to give the Dodgers their first championship in 32 years. His immediate celebration, a lunge and a howl, has become iconic. His agent, Scott Boras, gifted the family a canvas of it. His father has the image tattooed on his left arm.

That night in Culiacán, family and friends packed the house. Cars paraded up and down the street, honking as they passed. A banda showed up to play in the backyard. People danced until the wee hours.

“It was a special night,” Juana said.

Julio returned home that offseason with an idea. After visiting the president of Mexico in Mexico City, he met with the governor of Sinaloa in La Higuerita. They walked through the unpaved streets around his grandparents’ home, passed his first school and the neighborhood baseball field his grandfather Julián built with his brothers and friends in the 1960s.

“We all loved baseball,” Julián said with a Tecate Light in his hand and a Dodgers cap on his head. “We wanted to play it without having to go into the city. We didn’t have cars back then so it was hard.”

“It’s a dream come true for me and my family. I’ve always wanted to help my community, and to do that where my grandfather played is special.”

— Julio Urías on remodeling a baseball field in his hometown of Culiacán, Mexico

Julio remembered attending school with his shoes and uniform muddied in the rain. He envisioned an upgraded baseball facility — with grass — for children. As a newly crowned World Series hero, he recognized he had some sway, so he asked the governor if he could have the roads paved and the field remodeled. The governor agreed.

By the following spring, kids played at the renovated Unidad Deportiva Julio César Urías. The field at the complex was named after Paquin Urías, Julián’s brother, who led the effort to build the field six decades ago and died of COVID-19 complications in 2020.

Every weekday afternoon, Carlos and other former players, including Alba, work with children at the stadium for free.

“It’s a dream come true for me and my family,” Julio said. “I’ve always wanted to help my community, and to do that where my grandfather played is special.”

Carlos Jr. is an aspiring baseball player, too, but his career has been sidetracked. First by the same shoulder surgery Julio endured. Then, in June, by a more serious health scare.

What should’ve been a routine procedure to remove his appendix became a 21-day stay between two hospitals because of an infection. Julio was in Atlanta, hours from pitching against the Braves, when his family called. Carlos Jr. was scheduled for another surgery. They told Julio to say goodbye to his brother, just in case.

Julio limited the defending World Series champions to one run, striking out nine in a win hours later. His brother survived with a six-inch scar on his stomach. Julio’s 2.08 ERA in 14 starts since that day is tied for lowest in the National League.

This season, Julio’s stats have vaulted him atop the leaderboards and put him in the National League Cy Young Award conversation.

The Dodgers’ World Series hopes might hinge on his left arm. With Walker Buehler out for the rest of the season and Tony Gonsolin on the injured list for an unknown period. Urías is the ace of a rotation featuring Clayton Kershaw, Tyler Anderson, Dustin May and Andrew Heaney. If he stays healthy, he probably will be the team’s Game 1 starter for the first time in his career. He’s peaking with one season left before he becomes a free agent.

“I think Julio has been throwing the baseball as well as anybody in baseball, gosh, since the break,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said. “Even before the break, actually.”

The success hasn’t stopped the eye jokes. Last season, Julio said, a group of Mexican fans taunted him while he warmed up before a game in San Diego. They started with the usual banter. You stink. You’re no good. They’re going to kill you.

“Thank you,” Julio responded. “We’ll see a little later. The game hasn’t started.”

Then one of the men mocked his eye, striking a nerve. Julio turned around.

The Dodgers have qualified for the playoffs for the 10th consecutive season, but it’s going to be some time before they know who their opponent will be.

“I gave it to your team in the playoffs last year and I have a ring,” Julio said. “You guys don’t have anything. And that was with one eye. Imagine if I had two.”

The response, Julio remembered, silenced the group. It’s one reason why he doesn’t use social media anymore. Why, he reasons, open the door to negativity?

The eye wasn’t discussed for his recent start in Miami. The game, an easy 8-1 win for the Dodgers, ended at 1:21 p.m. in Culiacán. The room erupted in applause.

“I can finally breathe,” Juana said.

Julio earned the win. His family celebrated with carne asada, mariscos from a local spot and beer.

The next day, Carlos was driving, looking to stop somewhere for horchata de coco, when Julio video called from the visitors clubhouse in Miami. He showed his father a bandage on his left index finger.

“What happened?” the worried father asked.

“You didn’t notice it bothering me?” Julio said. “But I’ll be fine. It’s just a cut.”

Five days later, Julio didn’t skip a beat, holding the Padres to one run across six innings. Carlos watched from his living room, La Virgen shining in the hallway.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.