Commentary: Dodgers’ Dave Roberts calls out MLB for reducing opportunities for Black players

The word Dave Roberts kept coming back to was “uncomfortable.”

Jackie Robinson Day is the day Major League Baseball celebrates all it has done to bring Black people back to baseball. On this 75th anniversary of Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier, Roberts is using the day to call out MLB for cutting back on opportunities for Black players.

“It’s really hit me in the face,” Roberts said, “that I have to be uncomfortable.”

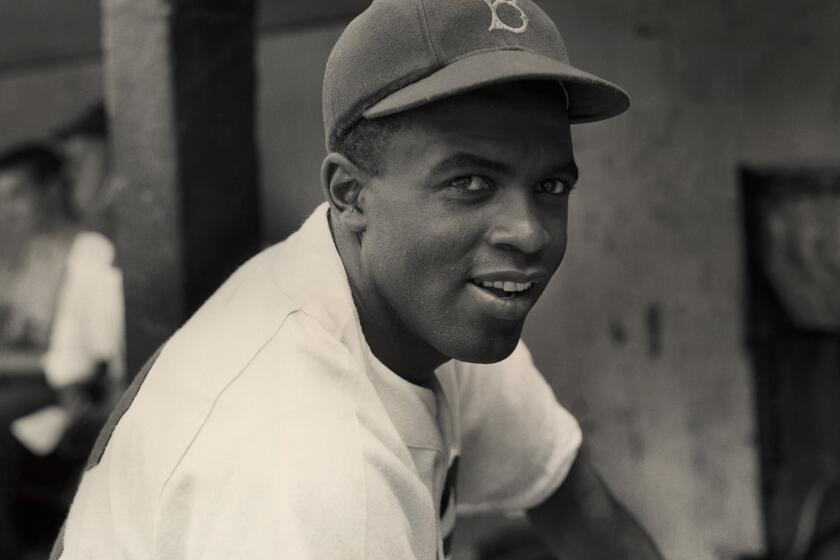

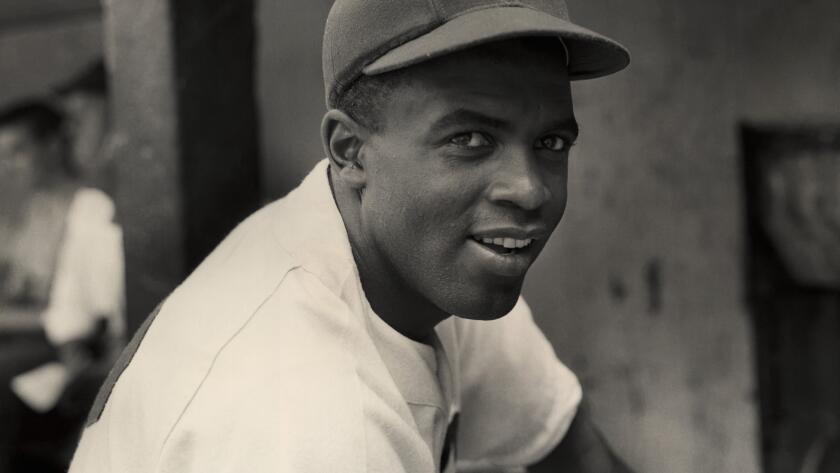

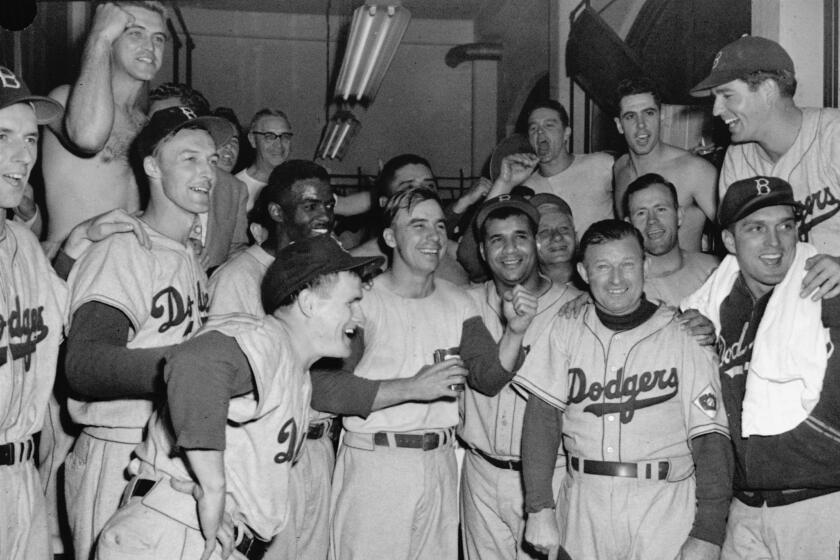

To call Robinson a Hall of Fame baseball player is a painfully incomplete description, almost a mythology. He was an activist for civil rights and for social justice.

In 1972, 25 years after he broke MLB’s color barrier, Robinson reflected on the ongoing fight for equality. Former Times sportswriter Ron Rapoport recounts that interview just months before Robinson’s death.

“Jackie Robinson made my success possible,” the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said in 1968.

On the 25th anniversary of his breaking the color barrier, Robinson accepted an invitation from MLB to be honored at the World Series. He ended his speech by calling out the league and giving voice to his hope that he might one day “see a Black face managing in baseball.”

Fifty years later, there are two Black faces managing in the majors, Roberts for the Dodgers and Dusty Baker for the Houston Astros. The percentage of African American players in MLB has fallen from 19% in 1986, according to the Society of American Baseball Research, to 7% on this season’s opening day rosters.

“When you’re talking about African American ballplayers, we need to do better,” Roberts said. “I think about it all the time. It’s really getting uncomfortable.”

Dave Roberts, Reggie Smith and Fred Claire reveal how the Dodger legend has influenced their lives.

As he grew into his position as manager of Robinson’s team, Roberts forced himself out of his comfort zone. In 2020, his players pushed not to play after Jacob Blake, a Black man, had been shot by police in Wisconsin. The game was postponed, and Roberts joined his players in protest.

“In years past, it would have been, ‘My job is to manage, and everything outside that is not my concern,’ ” he said.

In 2021, Roberts said he would consider not managing in the All-Star game after Georgia adopted restrictions on voting. MLB moved the game out of Atlanta, but not before Roberts said he “got a lot of blowback” for his remarks.

“In years past, I probably would not have even voiced that,” Roberts said.

“But it’s bigger than just my job. If Jackie were just a baseball player, I wouldn’t be here today, and the world would look different. And so I encourage our players to speak up and be advocates about the issues they believe in, and I have to follow that.”

On this day, Roberts wants to speak up about the draft.

“When you’re talking about African American ballplayers, we need to do better. I think about it all the time. It’s really getting uncomfortable.”

— Dodgers manager Dave Roberts

Baseball’s owners cut the draft from 50 rounds to 40 rounds in 2012, then to 20 rounds last year. They also eliminated 43 minor league teams, and with them about 1,000 players.

MLB has poured thousands of hours and millions of dollars into making baseball again a part of the Black community, establishing youth leagues across America in baseball and softball and partnering with Black churches and Boys and Girls Clubs on community programs.

Those ventures are an acknowledgment that Black athletes often have to be persuaded to play baseball and, when they do, they commonly start years behind competitors with the advantages of splendid facilities, first-rate coaching, and travel ball.

“When you’re talking about undeveloped, raw, talented African American players, that process takes time,” Roberts said. “It always has.

“When the draft is shortened, it just doesn’t give those same guys the opportunities. It also doesn’t give the organizations the opportunity to seek those guys or identify those guys.

“For me, you’re shortening the draft, you’re eliminating farm teams, you’re looking for more turnkey guys. The way the game has been for the last 20 years, those are people not of color.”

Said Baker: “When they cut the teams down, organizations don’t really have time to wait for development.”

The Kansas City Royals had 92 Black players on their draft board last year, according to president of baseball operations Dayton Moore. When the draft was over, Moore said, 47 of those players remained on the board.

If the draft had not been cut and the farm teams had not been eliminated, Moore said he believed the Royals could have placed as many as 22 of those players on one of their minor league affiliates.

“If we want African American players in the game, we have to draft them,” Moore said.

In 2015, when the Royals won the World Series, the player who scored the winning run in the clinching game was outfielder Jarrod Dyson, an African American the team drafted in the 50th round.

Owners cut so many rounds from the draft and so many minor league teams largely because of a cost-benefit analysis: Why pay to support so many players who would never see a day in the major leagues?

“I fear that, even though we are doing a spectacular job of trying to grow the game in the African American community, we’re hurting that progress with lack of opportunities.”

— Kansas City Royals president of baseball operations Dayton Moore

By the standard of financial efficiency, at least, the data support the owners. Baseball America reviewed two decades of drafts and determined a player selected beyond the 20th round had a 6.8% chance of spending even one day in the majors, and a 1.6% chance of spending three years in the majors.

That is not great, but it is not zero. Of the players on opening day rosters last season, according to Baseball America, 45 were drafted beyond the 20th round.

To Moore, the league is missing a bigger picture. The Black players who would be among those late-round picks, even the ones who might never blossom, are the ones who could go back home and apply what they have learned as the youth coaches and baseball evangelists so desperately needed within Black communities.

“I fear that, even though we are doing a spectacular job of trying to grow the game in the African American community, we’re hurting that progress with lack of opportunities,” Moore said.

At the top of the draft, the results have been spectacular indeed. The league runs a variety of developmental programs for elite Black athletes, with some events at the Dodgers’ former spring home in Vero Beach, Fla., since renamed in honor of Robinson.

Over the past decade, 17.5% of first-round picks have been Black, according to the league. At a time the league’s Black population is less than half that percentage, that is laudable and measurable progress.

The man charged with reclaiming baseball’s place within the Black community is Tony Reagins, a former Angels general manager. Reagins, who is Black, holds the title of MLB chief baseball development officer. All that the league does in that sphere — outreach programs, youth leagues, identification and development of minority prospects — falls under his portfolio.

Reagins does not challenge the criticism offered by Roberts, Baker and Moore.

“That’s fair,” Reagins said. “I think there is definitely an argument that less rounds mean less opportunity, but there also is an opportunity to go to college.

“What we need to do is to get more players, specifically African American players, playing college baseball.”

The NBA and NFL long have used college as a de facto minor league system, at no expense to the leagues. As MLB teams try to manage risk in the draft, college players can be more reliably evaluated than high school players because of the superior competition.

“They’re using college as a minor league proving ground,” Baker said. “They’ve got to get more scholarships.”

NCAA rules allow football teams to offer 85 scholarships but limit baseball teams to 11.7 scholarships. Reagins said MLB has considered how to subsidize those scholarships.

“Obviously, we would have to work with the NCAA to make that happen, but those conversations have taken place,” Reagins said.

“If I have to make an economic decision for my family whether to be a baseball player, a basketball player, or a football player, and I get a full ride if I play basketball or football but it comes out of my pocket if I play baseball, then the decision is pretty easy. We’re looking at, from a long-term standpoint, how we make our game more attractive than the other sports.”

Former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine was teammates with Jackie Robinson from 1948 to 1956. He recalls his relationship with the man who broke baseball’s color barrier.

It is unfortunate that the league has restricted draft opportunities in the short term without having that long-term solution in place. It is fortunate that Roberts feels strongly enough about that issue to speak up about it.

It has taken him a few years to understand that the manager of the Dodgers can speak about more than, say, why he took Clayton Kershaw out of a perfect game.

“I do see how people look at me, and look to me, for thoughts,” Roberts said. “It’s taken a while for me to adjust to that. But I think it’s important.

“I’m not a politician. I am a baseball manager. But I do have a platform.”

On this day, and on this subject, Robinson would have been proud of him for using it.