After 67 years of greatness calling Dodgers games, Vin Scully just wants to be remembered as a good man

The young man bid his mother farewell. It was his first day on the job, and he had a train to catch.

He was 10 months out of college, still living with his parents. The train carried him from New York to Philadelphia, and a taxi delivered him to Shibe Park.

It was opening day, the third Tuesday of April, in 1950. In Washington, President Truman threw out the first pitch. In New York, outfielder Sam Jethroe became the first African American to play for the Boston Braves. In St. Louis, catcher Joe Garagiola participated in the first night opener in major league history.

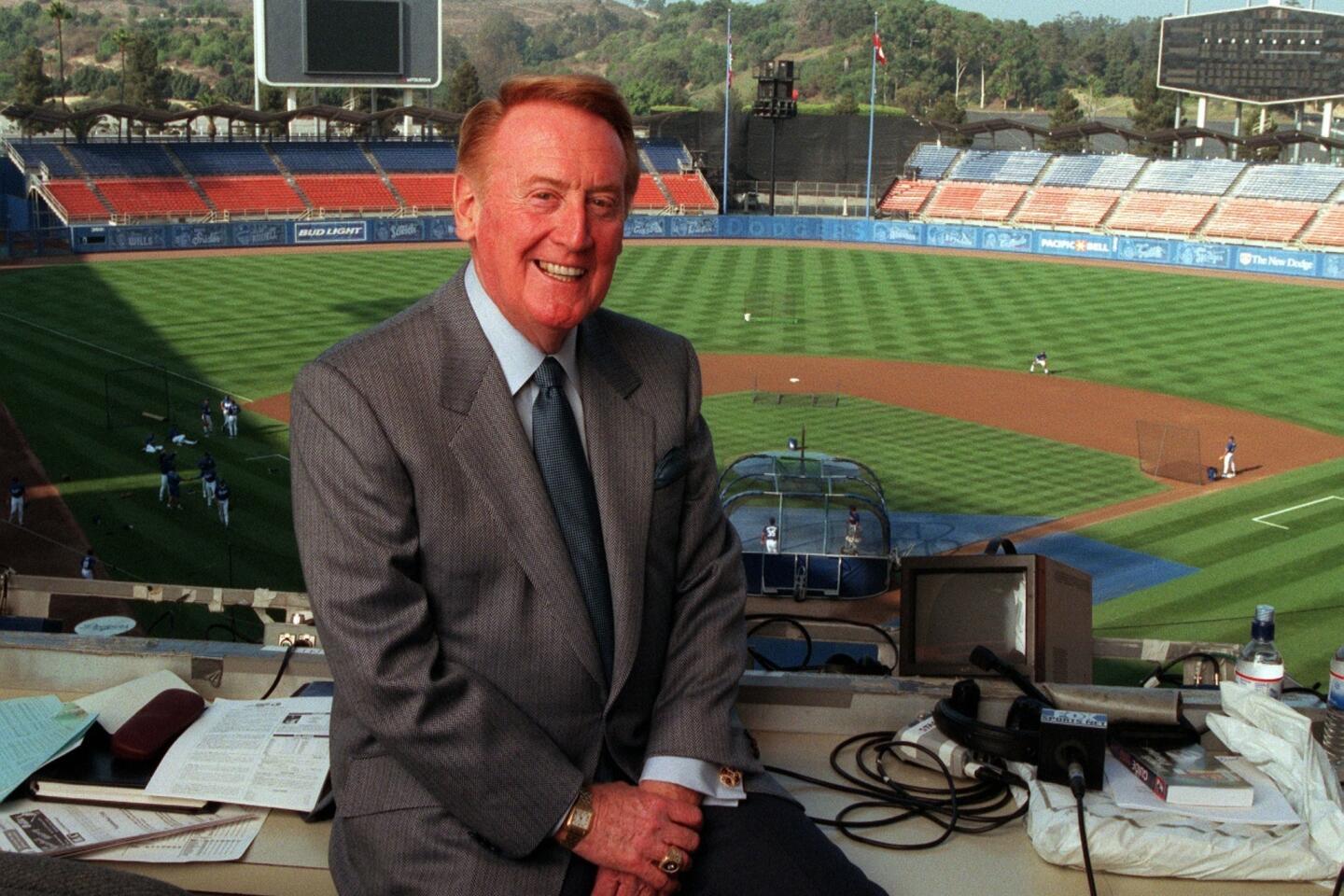

In Philadelphia, the young man with the red hair and the golden voice waited nervously. He was 22, the newest member of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ broadcast team. He would be silent for the first two innings.

In the third, on what was destined to be remembered as a very pleasant good afternoon, the Dodgers’ microphone first belonged to Vincent Edward Scully.

The Braves moved to Milwaukee in 1953, then to Atlanta in 1966. Shibe Park was demolished in 1976; its replacement was demolished in 2004. Garagiola and Scully would share the national television call of the Dodgers’ last World Series, in 1988. Eleven men have succeeded Truman, with the first African American president taking office in 2009.

One constant, through all the years, has been Scully.

I’d like to be remembered as a great husband, a great father and a great grandfather.

— Vin Scully

In one week, on the first Sunday of October, Scully will take a short ride along the streets of San Francisco from his hotel to AT&T Park. He will call his final game, between the team for which he rooted as a schoolboy and the team he served with unparalleled distinction.

Neither Los Angeles nor San Francisco had a team when Scully started his remarkable career, describing the feats of Jackie Robinson. When the Dodgers and Giants moved to California, so did Scully.

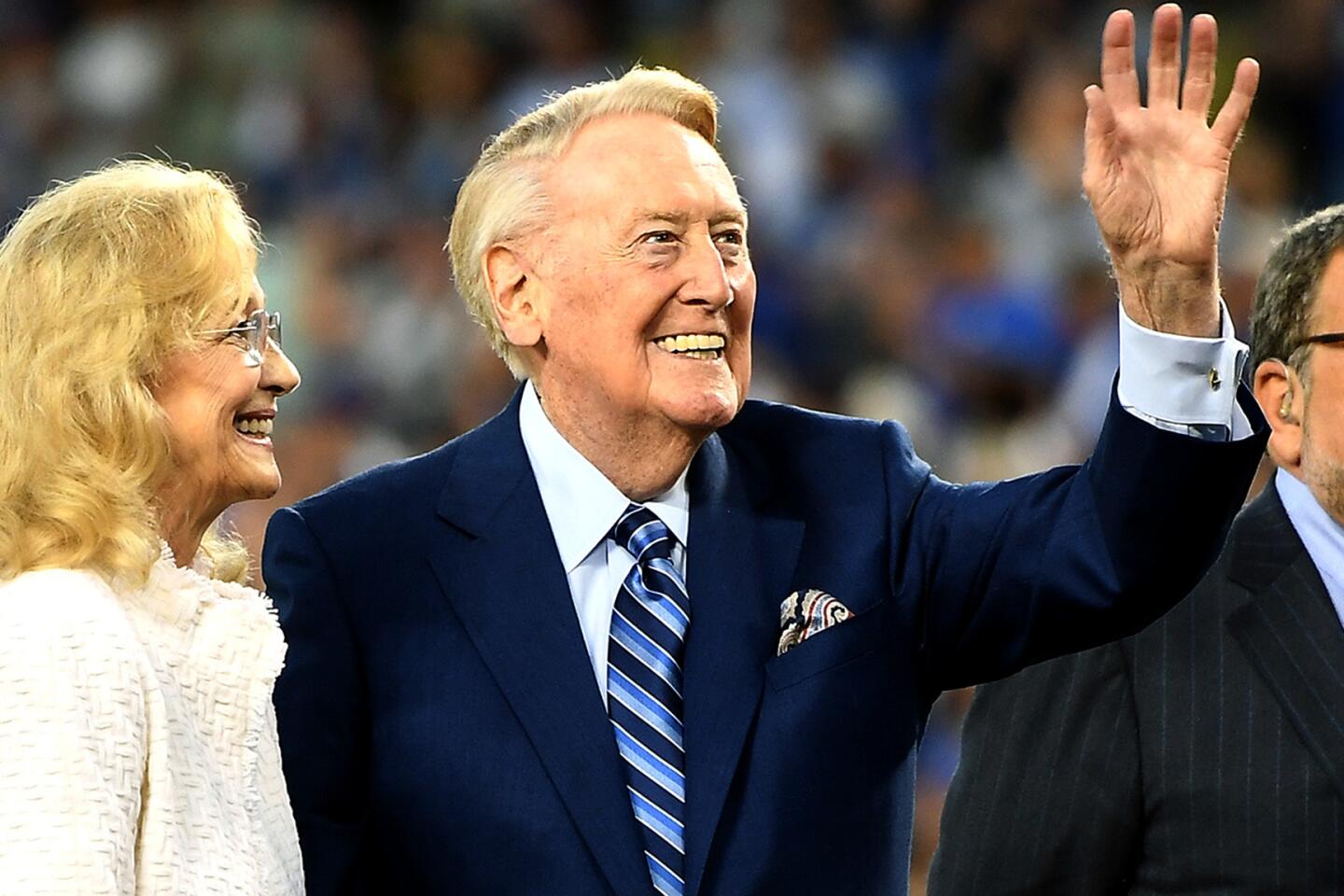

He courted L.A., on behalf of the new team and the new sport in town. In turn, L.A. embraced him, trusted him and loved him. The most popular and enduring of the Dodgers turned out to be the man behind the microphone.

After 32 years as voice of the Dodgers, he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, an award that traditionally caps an acclaimed career. Scully, 88, worked more years after his induction than before — 67 in all, the most by any broadcaster for any team.

The soundtrack to summer in Southern California is about to go silent. The retirement that all of Los Angeles dreaded for decades is upon us. As a grateful city tries to find the proper words to say thank you, the man who always picks the perfect words wants to say thank you as well.

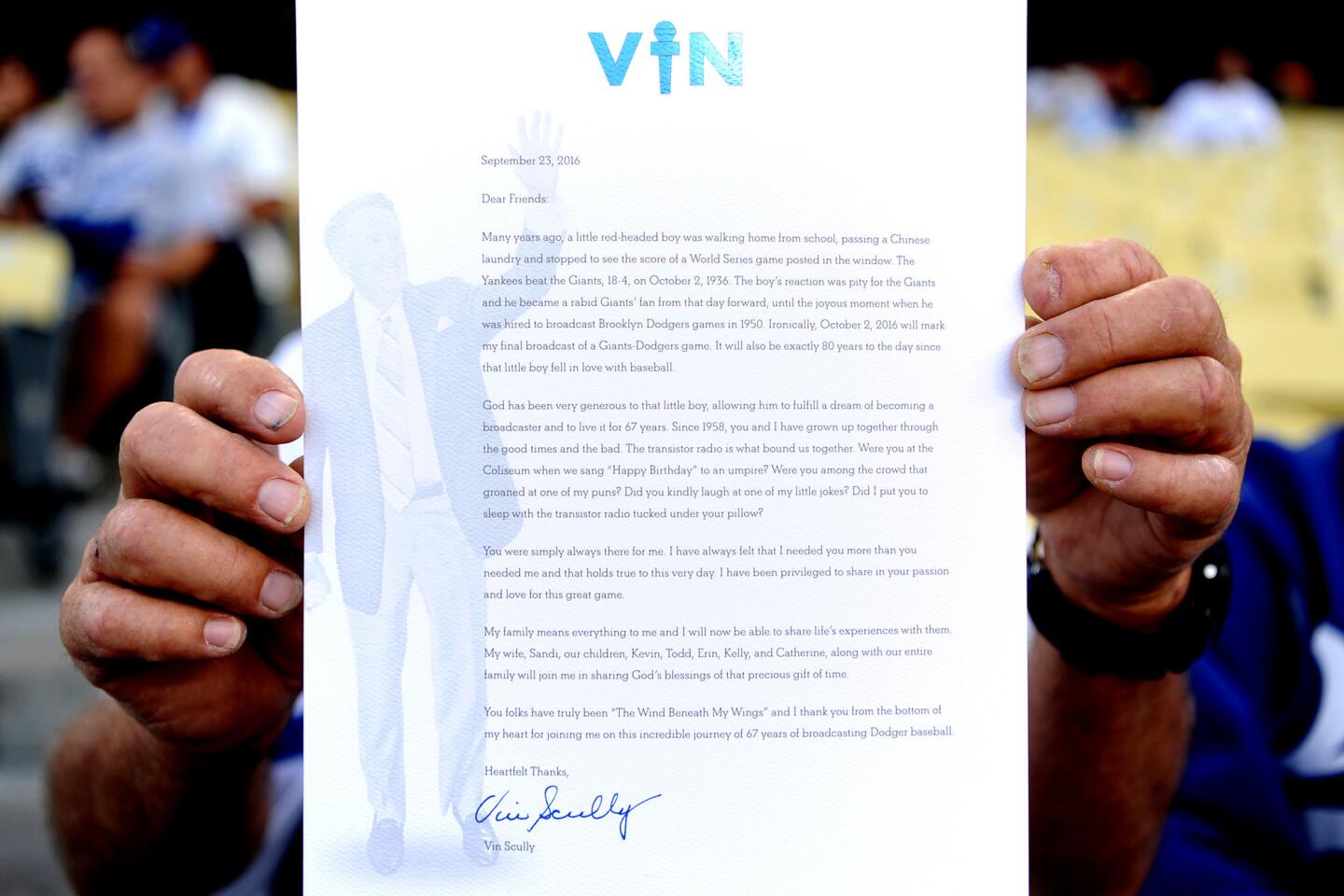

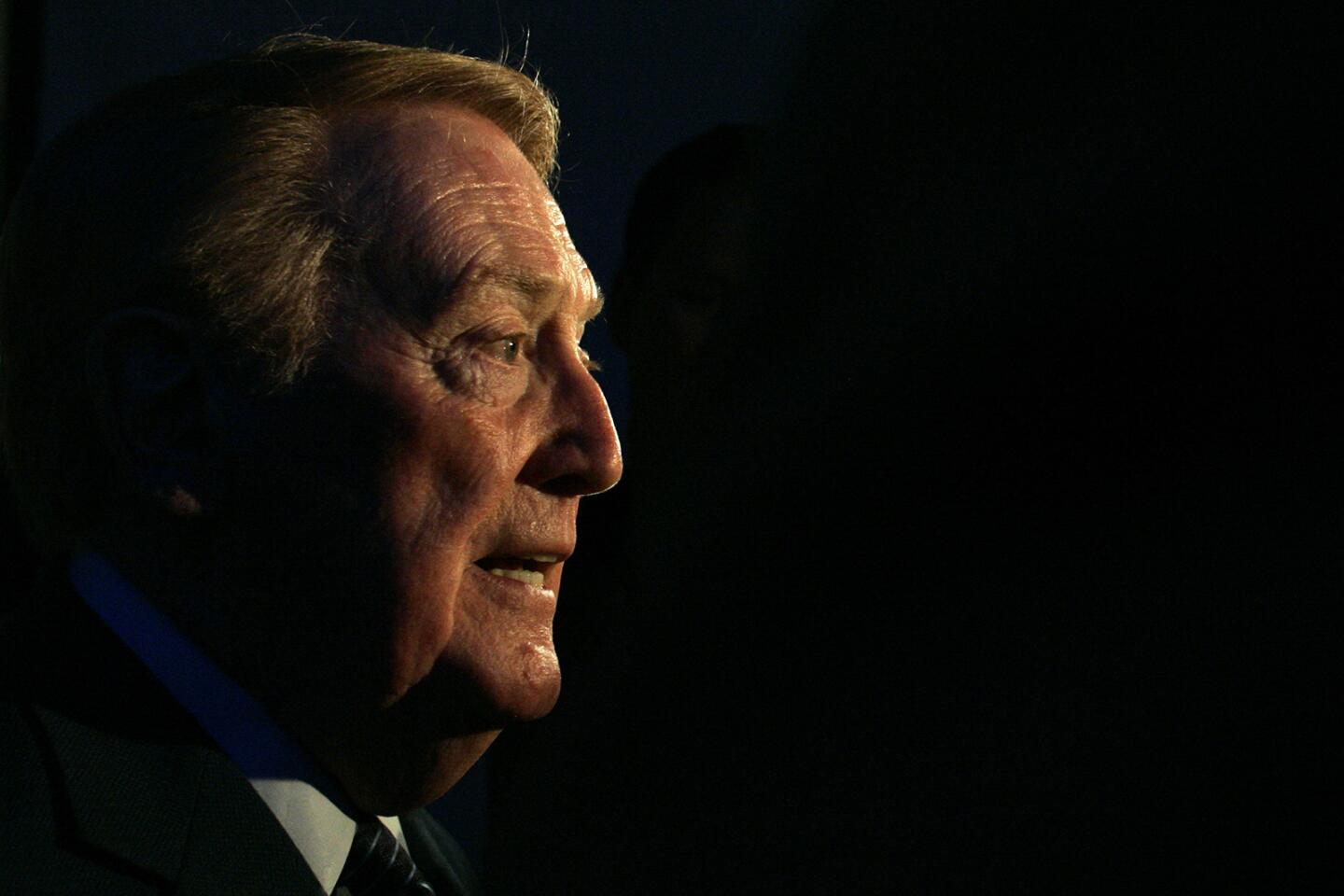

It is a measure of the man that the greatest broadcaster in baseball history pulled up a chair and sat down to write a farewell letter to Dodgers fans. It is another measure of the man that he does not wish to be remembered as the greatest broadcaster in baseball history.

“I would like to be remembered, No. 1, as a good man,” he said. “And, by being a good man, I mean as honest as possible. I’d like to be remembered as a great husband, a great father and a great grandfather. But I don’t really care about someone saying, ‘You’re the best broadcaster.’ That just happened. The others are far more important.

“I mean that from the bottom of my heart. That’s so much more important than anything else. And, in a sense, that’s one reason why I get so flustered about what is going on.”

He has been serenaded with tributes from coast to coast. Rival teams — even the Giants! — have silenced their own announcers for an inning, so their fans could hear Scully on the Dodgers’ broadcast.

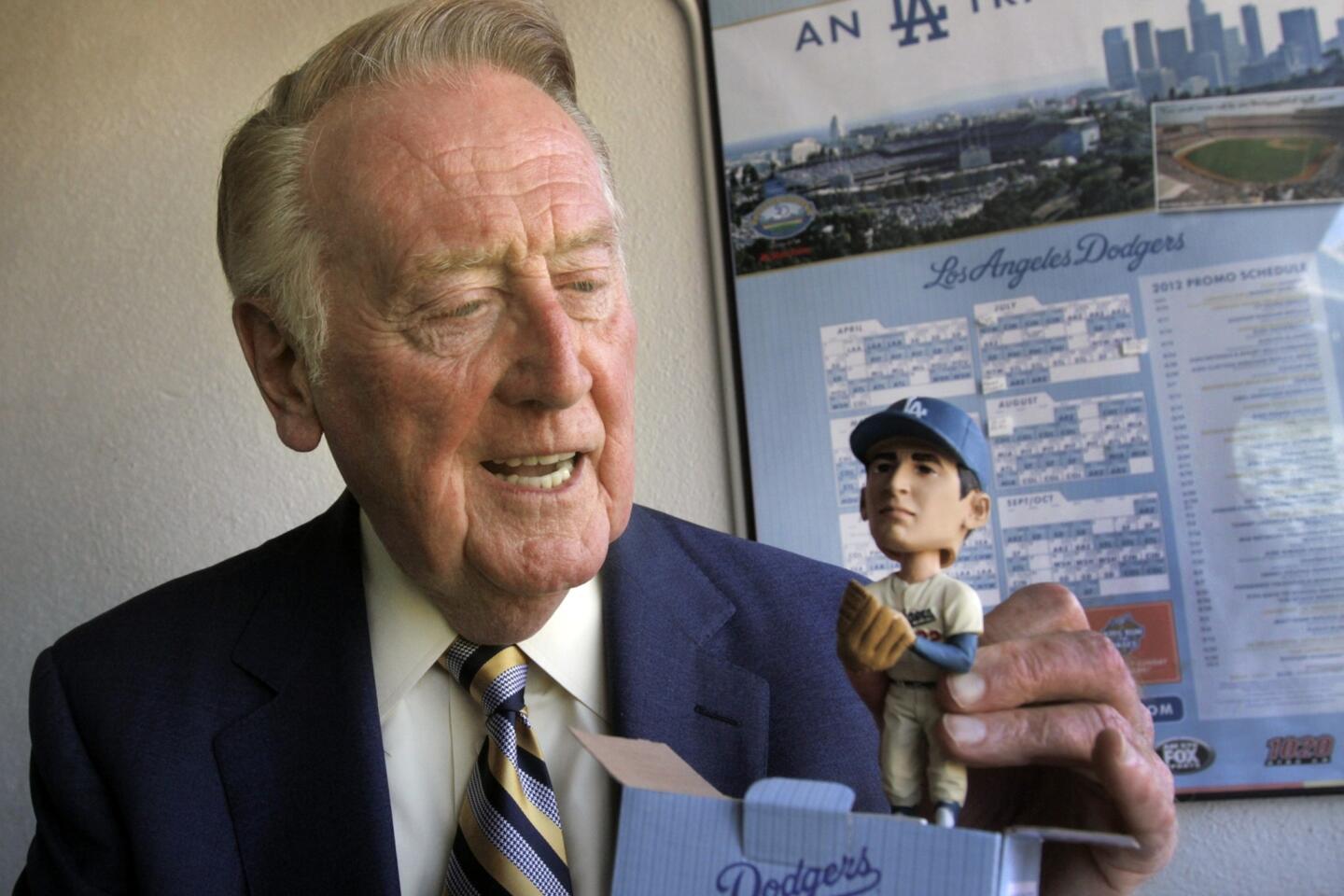

The Dodgers’ commemorative program for his final home games is headlined “The Greatest of All Time,” without dissension or qualification.

It’s all a bit much for Scully. The adulation is overwhelming, and uncomfortable. In his mind’s eye, he is the boy from the Bronx, the one who fell in love with sports broadcasting by setting a pillow on the living room floor, beneath the four-legged radio.

Television had not yet invaded American homes. The Great Depression lingered. Scully was 8.

He would get some crackers, and sometimes a glass of milk. He would crawl under the radio, listening to a college football game or a championship fight.

“I was absolutely carried away by the roar of the crowd,” Scully said. “It came out of the speaker like water out of a shower head, and I would get goose bumps and think, ‘Oh, my gosh. This is the greatest sound I’ve ever heard.’ ”

He never forgot. His greatest calls were so great not just because of his descriptions but because of his silences — for 38 seconds after Sandy Koufax completed his perfect game, for 68 seconds after Kirk Gibson hobbled off the bench to hit a walk-off home run in the World Series, for 103 seconds after Hank Aaron hit the home run that broke Babe Ruth’s record.

As Aaron circled the bases and fireworks erupted, Scully took off his headset, walked to the back of his booth and got a drink.

Scully never scripted a line, so he never felt compelled to interrupt the crowd noise, to stamp his words over the moment. He would wait for the roar to subside, and then he would say something — “In the year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened” for the Gibson home run; “A black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol” for the Aaron home run — that stamped his words on the moment anyway.

Scully aspired to be a writer. At Fordham University, he wrote for the school newspaper, with a part-time job at the New York Times. He also played center field for Fordham, including one 1947 game against Yale and its first baseman, George H.W. Bush. (Yale won, 3-1. Scully and Bush each went 0 for 3.)

“I remember I’d stand out there and broadcast the games to myself,” Scully told The Times in 1985, “although sometimes the priests sitting behind me in the stands would hear me and laugh.”

He got his break in radio, not in newspapers, graduating from Fordham in 1949 and landing a summer internship at a station in Washington, D.C. He got a bigger break that fall, when CBS Radio needed someone to call a football game between Boston University and Maryland.

His mother excitedly told him Red Skelton, the comedian, had called. It was Red Barber, who liked Scully’s work and ultimately invited him to join the Dodgers’ broadcast team the next spring.

In 1954, Barber switched to the crosstown Yankees, leaving Scully as the Dodgers’ lead announcer. On Oct. 2, 1955, Scully delivered what to this day remains his favorite call: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Brooklyn Dodgers are the champions of the world.”

Barber was born in Mississippi. Russ Hodges, the New York Giants’ announcer — “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!” — was born in Tennessee. Scully, the youngest among the voices of New York’s three major league teams, was the one from New York.

He befriended the players immortalized by author Roger Kahn as “The Boys of Summer” — including Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Roy Campanella and Duke Snider, Hall of Famers all — and called the long-awaited first title in Brooklyn history.

The last title, too. On Oct. 8, 1957, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley announced the team was moving to Los Angeles.

“All my friends, my relatives, my high school, my college, everything was back in New York,” Scully said. “It was a little scary.”

And not just because of geography. O’Malley was strongly advised to introduce the Dodgers to Los Angeles by dropping Scully and hiring local announcers, voices that would be familiar to the fans at a time the team would not be.

O’Malley stood behind Scully. That might have been our biggest break, but it was not his.

“My life is just full of breaks,” he said, “but the greatest single break was the transistor radio.”

When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, the transistor radio was the lifeline for the fan. The team played its first four seasons at the Coliseum, where a baseball diamond was uncomfortably wedged into one end of the football field, and fans seated toward the other end might be half a field away from the action, and 75 rows up.

Three calls that are arguably Vin Scully’s all-time best »

Scully narrated the game for them, for the fans listening on dashboard radios in this car-crazed city, for the fans listening in their living room because televised games were a rarity, and for the kids sneaking a transistor radio into their bedroom after a parent turned out the lights, or into their classroom when postseason baseball was played in the daytime and a teacher was not paying attention.

The fans were so far removed from the game at the Coliseum — a track circled the field — that Scully could one day ask them to say happy birthday to umpire Frank Secory without Secory hearing a word. Scully counted to three, and thousands of fans yelled, “Happy Birthday, Frank!”

Secory was startled. Scully was amused, just as he was on another day, when he joked that Joe Torre might be apprehensive about returning from third base to catcher after getting hit by a foul tip. If he were, Scully said, Torre would forever be known as “Chicken Catcher Torre.”

Said Scully: “The groan from the crowd … was something that I’ll still remember to my dying day.”

In 1959, their second season in Los Angeles, the Dodgers won the National League championship playoff, and with it a spot opposite the Chicago White Sox in the World Series.

“Up with it is Mantilla, throws low and wild!” Scully cried. “Hodges scores! We go to Chicago!”

In retrospect, to hear Scully use the word “we” is disconcerting. It must have been a youthful indiscretion, because he takes great pride in describing the Dodgers’ performance honestly and objectively.

If one of the Dodgers botches a play, Scully says so, building trust with his audience. He might be universally popular outside the Dodgers’ clubhouse but occasionally has ruffled feathers inside it, because announcers for other teams sound more likely to cozy up to players rather than criticize their performance.

In 2008, Dodgers second baseman Jeff Kent became one of the few brave souls to publicly say a cross word, after Scully suggested — with statistics to support his thesis — that Kent hit better with Manny Ramirez batting behind him.

“Vin Scully talks too much,” Kent said.

On matters off the field, Scully steadfastly avoided controversy. While many fans pleaded for him to lend his powerful voice to the cries against former owner Frank McCourt, who took the team into bankruptcy, and against the Dodgers’ television deal that kept Scully off the air in a majority of Southland homes for the final three years of his career, he remained silent.

He was stung — “flabbergasted” was his word — after Mike Piazza claimed in his 2013 autobiography that Scully had turned Dodgers fans against him during the contract dispute that preceded his trade to the Florida Marlins.

“Vin Scully was crushing me,” Piazza wrote.

Scully said he had done nothing of the sort because he never would take sides in contract negotiations, or even discuss them on the air with more than a passing reference.

“As God is my judge, I don’t get involved in these things,” Scully told The Times.

Scully would rather tell stories. He did not talk to broadcast partners because he had none. He talked to you.

He engaged in conversation with his audience, collecting anecdotes about players and about life, weaving them seamlessly into his game description. Whenever well-traveled infielder Dan Uggla came to bat, Scully joyfully related that “Uggla” is Swedish for “owl.”

In one half-inning this year, inspired by a wave of bearded players, he told the history of beards, dropping Leviticus, Deuteronomy, Alexander the Great and Abraham Lincoln into the broadcast without missing a pitch.

Bud Selig, who retired last year after more than two decades as baseball’s commissioner, likes to say that he asked to be put on hold whenever he called the Dodgers, just so he could hear the Scully highlights the team played in place of recorded music.

That Mantilla call — and the 1959 season — so enchanted Los Angeles that the Dodgers sold a phonograph album of Scully’s highlights from the championship year.

The Dodgers won the World Series three times in their first eight seasons in Los Angeles, moving into a new stadium with breathtaking views of the mountains on one side and the downtown skyline on the other. Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Maury Wills captured the fancy of the town.

So did Scully. As the Dodgers won, his popularity increased, and listening to Scully from the stands became as much a part of the Dodger Stadium experience as eating a Dodger dog, transistor radios buzzing from every direction. If you did not bring a radio, certainly the folks sitting behind you did.

“I’m in the batter’s box,” Torre told the New York Daily News, “and you can hear Vin Scully.”

Before long, America could. Over the years, Scully called the World Series and the Game of the Week for NBC. He called the World Series for CBS Radio. He called golf, tennis, and the NFL.

In the last minute of his last NFL broadcast, he described “The Catch,” Joe Montana to Dwight Clark in the NFC championship in the 1981 season, sending the San Francisco 49ers to the Super Bowl: “Montana … looking, looking, throwing in the end zone … Clark caught it! Dwight Clark!”

Then the Scully trademark: 27 seconds of silence, as the crowd went nuts. “It’s a madhouse at Candlestick!” he finally said.

He hosted a game show, a talk show and the Rose Parade. He appeared in movies and on television — including in an episode of “The X Files,” a series in which one of the lead characters is named in his honor: FBI Special Agent Dana Scully.

But, like a swallow returning to Mission San Juan Capistrano, Scully always returned to the Dodgers. In 1976, fans voted him the most memorable Dodger, and we have enjoyed his company for another four decades, treasuring the turns of phrase that generations of listeners can recite right along with him.

Two balls, two strikes, two on and two out? “Deuces wild.”

An ex-Dodger? “Old friend.”

The fans interested in a particular player? “Marching and chowder society.”

A player is listed as day-to-day? “Aren’t we all?”

The Farmer John slogan, so lyrical when Scully said it: “Easternmost in quality, westernmost in flavor.”

His timeless opening: “It’s time for Dodger baseball!”

It is almost time for Dodger baseball without the voice of the Dodgers. And the voice wants to go quietly.

Joe Buck offered to let Scully call this year’s All-Star game in his place. Torre asked him to New York this month, to call one last Dodgers-Yankees series at Yankee Stadium. Dick Enberg invited him as a house guest this week, so they could call one last series together in San Diego without Scully being swamped by well-wishers on the short walk from the Dodgers’ hotel to Petco Park.

Scully declined all. He simply wants to sign off and get on with the rest of his life, with his wife, his 16 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

On Sunday, for the last time, Scully can follow his Sunday routine at Dodger Stadium. In the morning, several hours before game time, he takes an elevator to the lowest level of the stadium and walks into a room normally reserved for news conferences. Catholic Mass is offered for team employees there, and Scully always participates, the announcer in the suit and tie shoulder to shoulder with the stadium workers in the lime green jerseys.

This is not a sad day. This is thanksgiving day, for him and for us.

“God has been incredibly kind to allow me to be in the position to watch and to broadcast all of these somewhat monumental events,” Scully said. “None of those are my achievements. I just happen to be there.”

MLB Playlist

Twitter: @BillShaikin

ALSO

Dodgers fans vote on Scully’s top calls

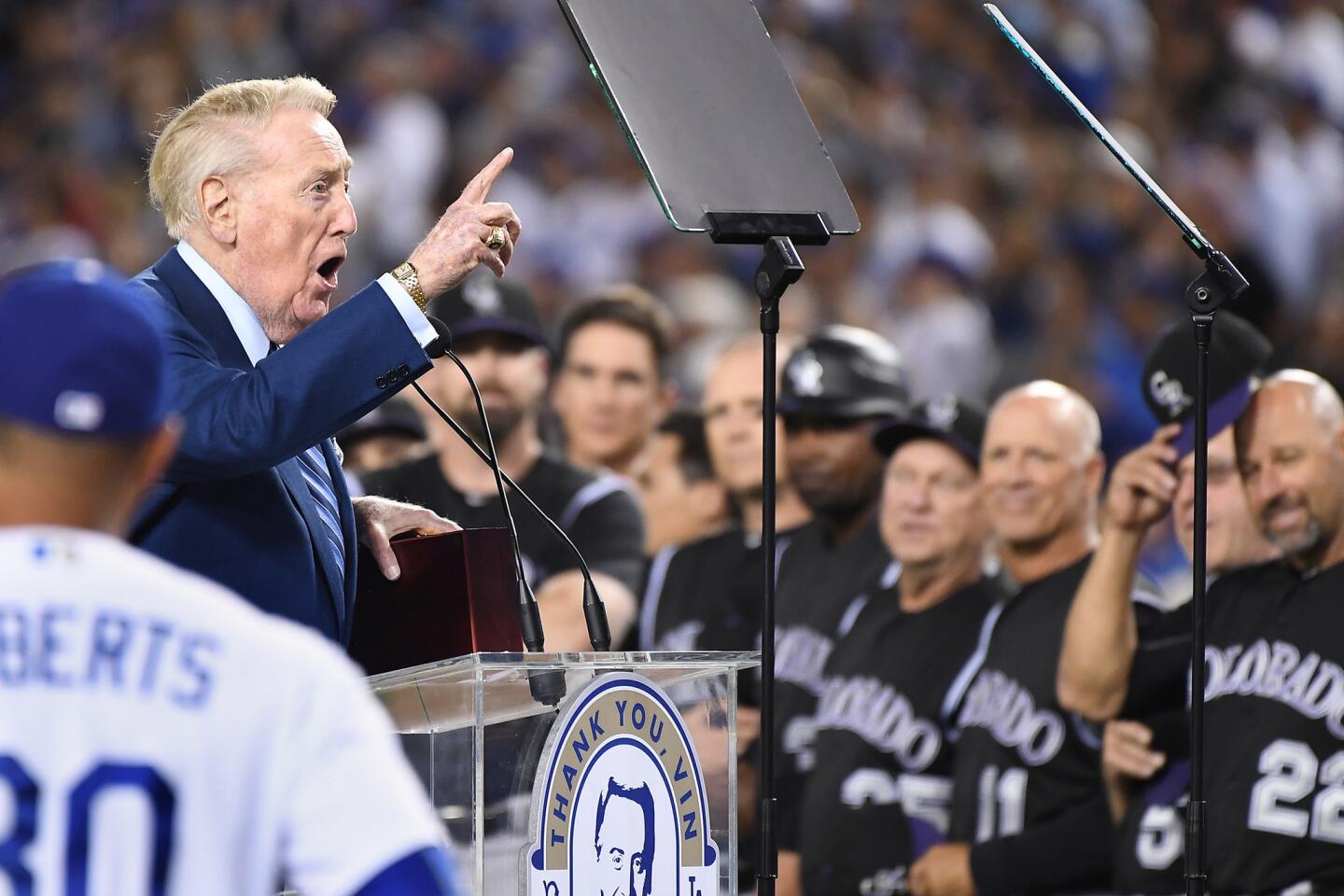

In his words: Vin Scully shares his ‘Thanksgiving’ with Dodger Stadium crowd

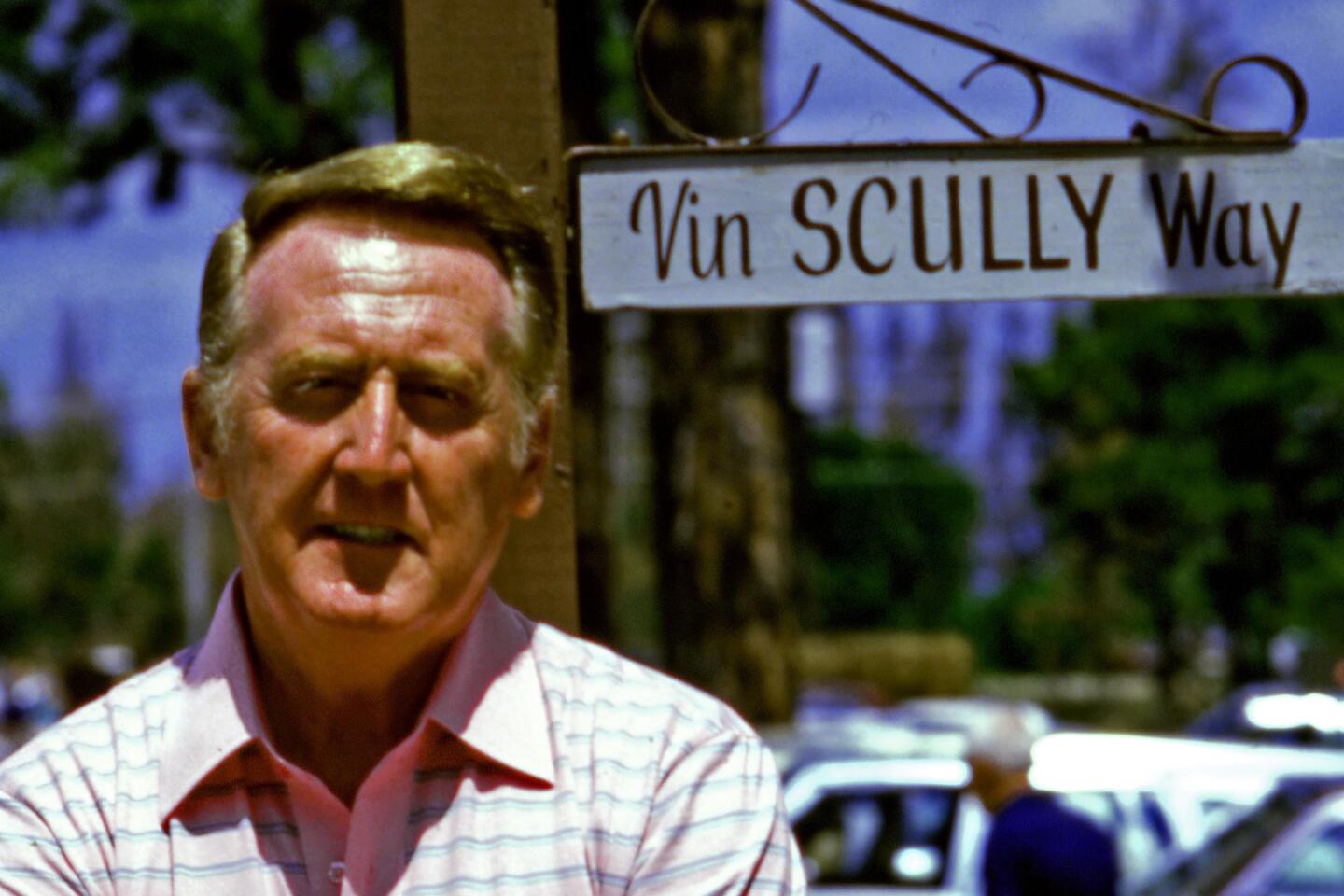

Take a walk, light a torch, and salute Vin Scully, L.A.’s most-beloved public figure

Vin Scully writes a letter to Dodgers fans