In Anaheim’s Platinum Triangle, affordable housing is nonexistent — and there’s little room left to build

Behind the Stadium Lofts in Anaheim’s Platinum Triangle, a Brewheim bartender filled another glass of beer on tap. The brewery is one of many to dot the area around Angel Stadium in an effort to make the city a hops haven where the once mighty “Tile Mile” stretch along State College Boulevard is slowly chipping away.

There’s even a signature blond ale that’s refreshingly crisp, lightly tarty and dubbed “Platinum Triangle” in tribute to the brewery’s slice of “heim,” or home.

Wrapping up an afternoon of drinking, a couple signed off on a receipt at the bar.

“We live in the Platinum Triangle,” a woman said of the nearby luxury apartments before adding a tip. “I guess we’re called the Paramount now.”

“Oh, we still do discounts for residents,” the bartender said.

It’s an offer that not everyone can cash in on.

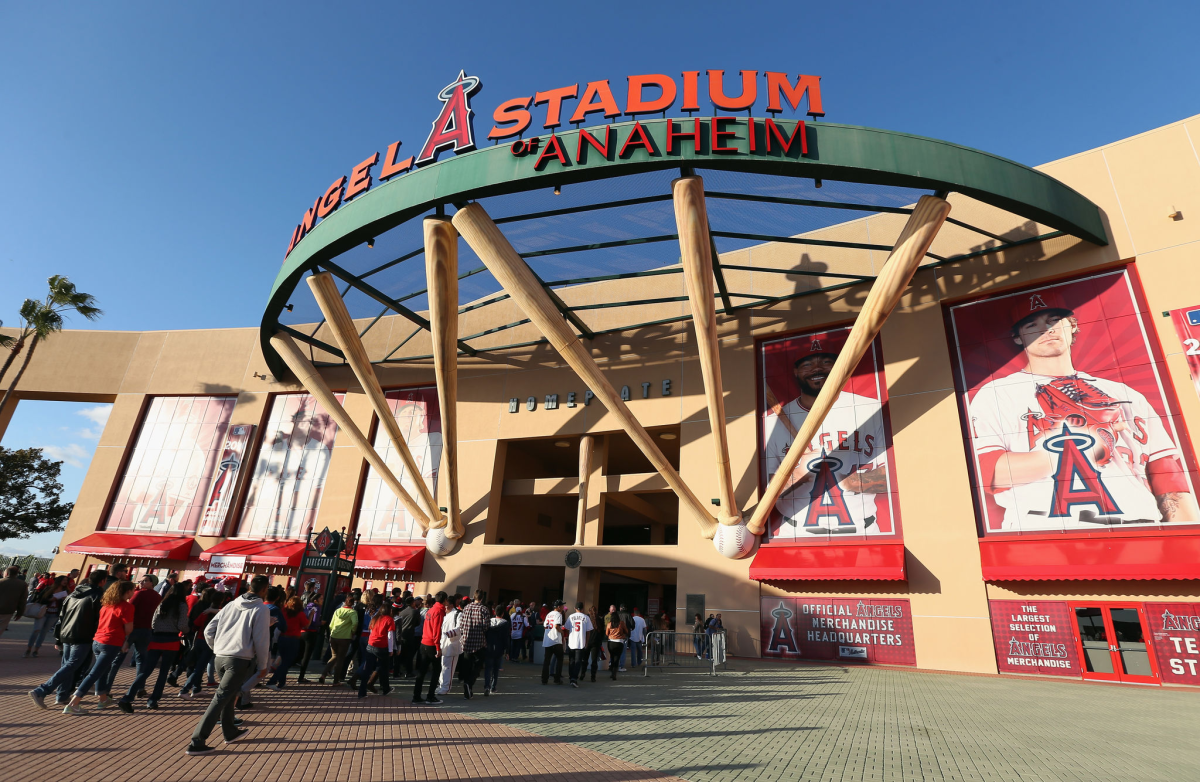

Fifteen years after Anaheim City Council paved the way for up to 19,000 homes to be built in the Platinum Triangle through rezoning, the lofty vision of creating a “city unto itself” around Angel Stadium that doubles as Orange County’s downtown hasn’t included any affordable housing units to date.

Not at the Vivere Lofts. Not at A-Town. Not at the George.

Throughout all of the Platinum Triangle’s 820-acres, it’s anything but isosceles.

“While encouraged by the city,” said Mike Lyster, Anaheim spokesman, “no affordable housing has been built.”

When completed, 26,000 residents are expected to call the Platinum Triangle home, a boost that will help Anaheim retain its status as O.C.’s biggest city.

And, according to city statistics, there’s little room left to spare.

Of 17,501 dwellings units planned for the area, 5,834 have already been completed, 6,295 have been approved, and 108 are under construction.

That leaves just 5,264 units on the books.

One of the last quarters to create some semblance of housing equity in the Platinum Triangle is also its controversial centerpiece: 150 acres of land surrounding Angel Stadium, whose future has become the site of a pitched battle between the state housing agency and the city.

In December 2019, an Anaheim council majority approved the sale of the city-owned property to team owner Arte Moreno’s SRB Management Co., which plans to transform a vast swath of parking lot gray into a vibrant ballpark community anchored by restaurants, retail, office space and housing.

The negotiated selling price: $320 million.

Under the sale, Moreno is also set to receive $170 million in community benefits credits, in part for a city requirement to include at least 466 affordable housing units within its plan to build 5,175 apartments and condominiums at the stadium site.

Of those, 207 would be “very low,” or households at 50% of the $106,700 county median income, and 259 would be “low,” or 80% of the county median income; SRB Management plans to add 259 moderate, at 120% of the county median income, and 52 low-income units at no cost to the city.

Anaheim Mayor Harry Sidhu beamed with civic pride during his State of the City address last year.

“It will be the largest expansion of affordable housing in our city’s history,” he said.

But the Kennedy Commission, an Irvine-based housing advocacy group, saw a violation of the state’s beefed up Surplus Land Act and warned city officials as much at least three times beforehand.

“The main intent under the Surplus Land Act is to look at public property and see how it can be prioritized for affordable housing or open space,” said Cesar Covarrubias, the nonprofit’s executive director. “When the deal moved so quickly and the city selected one entity to negotiate with, it clearly became apparent to us that there was a violation to the spirit and to the law of the Surplus Land Act.”

The California Department of Housing and Community Development agreed and deemed the sale illegal last December. The agency gave Anaheim 60 days to remedy it or face a $96-million fine. Anaheim responded in February by asking that the “erroneously issued” violation be rescinded.

But the battle over affordable housing in the Platinum Triangle predates the stadium squabble.

In 2004, Anaheim rezoned the triangular-shaped industrial area anchored by Angel Stadium to encourage residential and commercial development through a change in its General Plan.

The Stadium Lofts was the first mixed-use project to break ground that year.

Amid a slumping housing market in 2007, council members doubled the number of housing units permitted through more rezoning. Democratic Councilwoman Lorri Galloway opposed the expansion for its lack of affordable housing.

A Community Benefits Coalition, which the Kennedy Commission belonged to, issued a report in 2009 that pushed for more equity in the Platinum Triangle.

“New housing must be in line with the types of jobs created,” the report argued. “Proposals for mixed-income housing development are called for, as mixed-income development reduces over-concentrations of poverty in one area.”

After casting off the Great Recession’s gloom, development stirred in the Platinum Triangle anew last decade, but without much consideration of very low- and low-income housing.

In the wake of failed negotiations with Moreno on a lease agreement framework for the stadium land in 2013, LT Global Investment proposed a $500-million residential, hotel and retail development atop a 15-acre site that included 1,500 parking spaces next to the stadium.

The Angels initially opposed the project and appealed the Planning Commission’s recommended approval; council unanimously approved “LT Platinum” in 2016 after it scaled down $50 million and backed away from seeking to share part of the parking lot.

“The most important thing that LT Global’s proposed development had to offer the Platinum Triangle was a grocery store,” said Grant Henninger, a former planning commissioner who voted in favor of it. “It’s a real failure that the Platinum Triangle doesn’t have any of the amenities it needs to feel like a real neighborhood. It’s turned into a collection of self-contained communities.”

But LT Global’s plans didn’t include any affordable housing among its proposed 405 units — nor was it required to.

“That speaks to the challenge of providing affordable housing in the Platinum Triangle, where developers face high land and construction costs,” Lyster said. “That is why the city is including and accepting as part of payment affordable housing in the stadium site plan.”

LT Global sold the property in 2019 and the development agreement has since lapsed.

Meanwhile, a traditional “circuit” of rotating service sector jobs in Anaheim’s sports and entertainment economy took a union hit. Chris Smith, a bartender who mainly worked at the Honda Center, picked up jobs at Angel Stadium during summer baseball season and at the Anaheim Convention Center for events.

“I’m probably the poster child for that,” he said, with a laugh.

In 2013, hundreds of Aramark concession workers represented by Unite Here Local 11, including Smith, received layoff notices as the arena’s management company decided to bring jobs in-house, instead. That same year, the Angels dropped Aramark in favor of Legends Hospitality, but the union successfully fought to maintain its membership.

After the layoff, Smith moved from Los Angeles to the Inland Empire and still works at Anaheim Convention Center.

“Just commuting nowadays is super expensive,” Smith said. “Having a job in your neighborhood where you can earn a good wage is important. If you had affordable housing close to where you work, that would help so many families.”

Before the Angel Stadium deal, the city struck an agreement in 2018 with Henry and Susan Samueli, owners of the Anaheim Ducks, which allowed them to buy city-owned parking lots around the arena as well as taking over management of the nearby Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center.

It came well before the Surplus Land Act was updated to include local agencies.

The Samuelis submitted plans to transform the area into OC Vibe, an entertainment hub complete with a new 6,000-seat concert venue, two hotels, restaurants, retail and 1,500 housing units. The developer included 195 affordable units, with 66 at very low income levels, which allowed the project to qualify for a 20% density bonus under city code.

Once approved, OC Vibe will leave the number of remaining permitted housing units in the Platinum Triangle to just 3,764.

Without an affordable housing ordinance on the books, how the last of that housing stock is allocated by future development remains to be seen.

So far, the Platinum Triangle hasn’t helped Anaheim meet its Regional Housing Needs Assessment requirements for affordable housing.

Between 2014 and 2020, above-moderate units built citywide outpaced the number of low- and very low-income units by 16-fold.

“More housing expands overall supply and limits increases in housing costs by creating new places to live and freeing up existing homes elsewhere in our city,” Lyster said. “We have also worked with nonprofit partners to open new affordable communities in our city. But building affordable communities is more challenging with high land costs, construction costs and finding developers to build.”

The city touts 14 dedicated affordable communities outside the Platinum Triangle as three apartment communities within it are converting into workforce housing.

But a proposed compromise on the stadium deal almost shifted the imbalance further.

In negotiating with the state housing agency before the sale was deemed illegal, Anaheim offered to boost affordable housing overall. The city offered 518 very low- and low-income housing units to be built more immediately within 10 years but off-site.

The 777 units still slated for the stadium site would all be at the moderate tier.

“The affordable housing that the city needs is very different than the affordability that the developer wants to give,” Covarrubias argued.

Anaheim claimed the offer would exempt the land from the law by upping affordable housing to 25% of the total units built.

Deeming it “a bridge too far,” the state housing agency rejected the proposal.