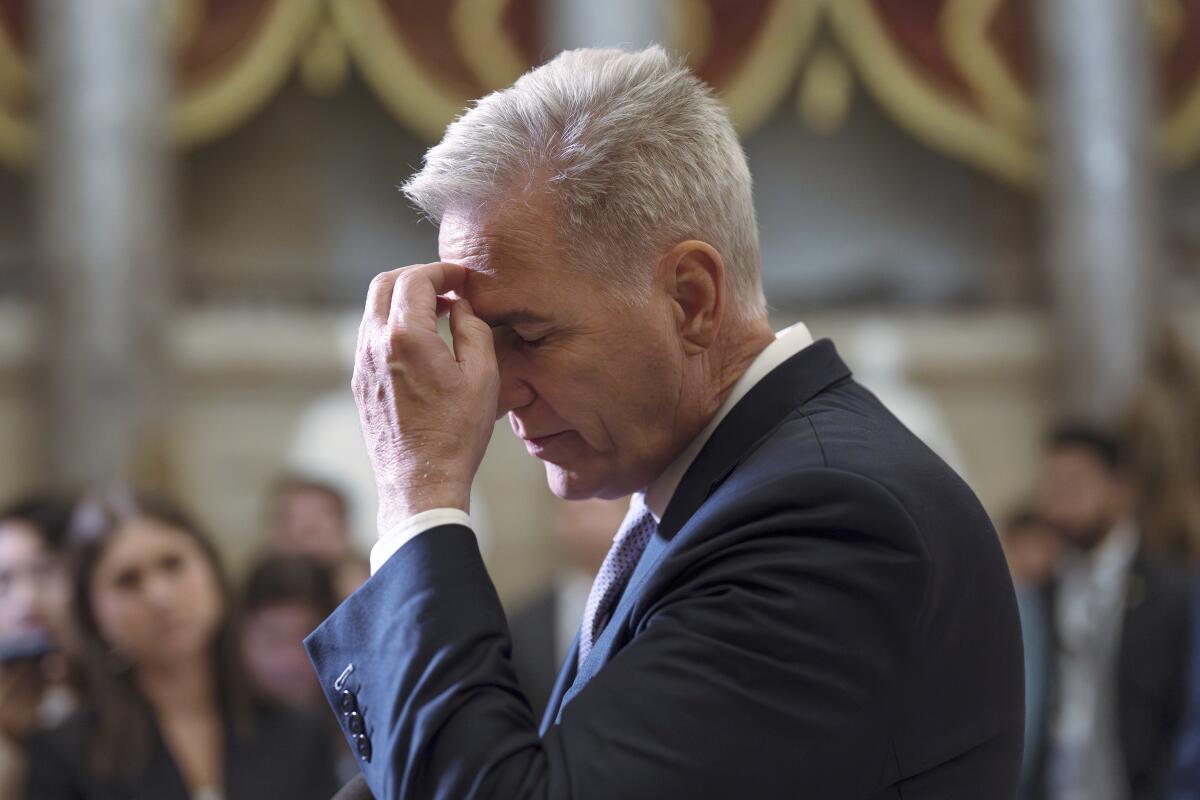

News Analysis: Kevin McCarthy avoided a government shutdown. But the fiasco shows he’s weaker than ever

WASHINGTON — Kevin McCarthy’s struggle to become House speaker should have been the most embarrassing moment in his political career. The U.S. House of Representatives had to vote 15 times before he was able to secure enough support in his party to lead the lower chamber.

But months later, the fight over whether to fund or shut down the federal government is the latest in a series of humiliations.

The speaker failed to get his party in line and had to rely on Democrats to pass a resolution funding the government for about seven more weeks, which would delay a potential shutdown until Nov. 17.

The House approved the short-term funding Saturday afternoon, 335 to 91, with Democrats overwhelmingly backing the resolution. The Senate approved the resolution late Saturday in an 88-9 vote, and President Biden signed it before midnight, ensuring the federal government would stay open.

The short-term House spending resolution did not include military aid for Ukraine. The White House has signaled it wants Congress to pass supplemental funding to help the war-torn country fend off Russia’s invasion.

In a floor speech ahead of the Senate vote Saturday, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said that his caucus will “remain committed to help our friends on the front line,” and that he was “confident the Senate will pass further urgent assistance to Ukraine later this year.”

McCarthy has not committed to giving Ukraine funding a separate vote on the House floor.

But the Republican speaker’s need to rely on 209 Democratic votes to fund the government leaves him weaker than ever. Only 126 Republicans voted for the extension.

Jay Obernolte (R-Big Bear Lake) was the only California lawmaker to vote against the resolution. Rep. Katie Porter (D-Irvine), who is running in the 2024 race to fill the late Dianne Feinstein’s Senate seat, did not vote. “The congresswoman had a family commitment that forced her to head back to California,” Porter spokeswoman Lindsay Reilly told The Times.

The longtime senator from California died this week at her home in Washington. But she worked until her final hours.

House Democrats had asked for more time to examine the 71-page resolution, which they complained had been given to them less than one hour before the scheduled vote. Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) used his “magic minute,” an unlimited floor speech only party leaders can give, to speak for 45 minutes Saturday afternoon, giving his allies more time to read the proposal.

For much of September, a handful of conservatives repeatedly torpedoed McCarthy’s spending bills, sinking any hope of projecting Republican unity to Senate Democrats and Biden.

The 45-day funding resolution only delays McCarthy’s inevitable choice: Shut down the government, or betray the conservative hard-liners who can make or break his speakership — and enrage former President Trump, who has made clear he wants to see the government shut down unless far-right Republicans get everything they demand.

The hard-liners, including Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Dan Bishop of North Carolina, Matt Gaetz of Florida and Andy Biggs of Arizona, all voted against the resolution to temporarily fund the government. Trump has egged on the group, repeatedly saying he’s eager to see the government shut down.

“It is clear that I tried every possible way, listening to every single person in the conference,” McCarthy said in a news conference after the vote.

“I don’t want to be a part of that team,” he said of the far-right members who wouldn’t budge. “I want to be part of a conservative group that wants to get things done.”

After the vote, House conservatives expressed ire that McCarthy had relied on the Democratic minority to delay the shutdown. In a tweet, Biggs referenced hard-liners’ long-standing threat to oust McCarthy from the speaker’s chair.

“Instead of siding with his own party today, Kevin McCarthy sided with 209 Democrats to push through a continuing resolution that maintains the Biden-Pelosi-Schumer spending levels and policies,” Biggs tweeted. “He allowed the DC Uniparty to win again. Should he remain Speaker of the House?”

In his news conference, McCarthy dismissed threats to overthrow him, saying that “if somebody wants a motion against me, bring it. There has to be an adult in the room.”

It remains unclear what policy wins House conservatives can realistically hope to secure with Democrats in control of the Senate and the White House. But it is clear that a shutdown is unlikely to sit well with voters.

At the California GOP convention in Anaheim, attendees were more interested in visiting presidential candidates or local matters than the potential federal government shutdown.

Shutting down the government has never worked to Republicans’ advantage, said Ed Rollins, a GOP strategist and former senior advisor to President Reagan.

“You get blamed for it,” he said. “A lot of people are unhappy about it. They see no purpose in it.”

“Kevin is in a very precarious situation,” Rollins added.

McCarthy is the most visible Republican in Congress, and the role of speaker usually commands authority and respect from one’s party. But is the speakership worth all of this indignity?

“There’s no secret: There’s a giant leadership vacuum in the Republican Party,” Alex Conant, a GOP strategist, told The Times. “We’re seeing that play out on the House floor, where nobody can force every member to fall in line.”

Historically, when Republicans have shut down the government, they had a clear objective. The last shutdown occurred under then-President Trump, when Republicans controlled Congress, over funding for a wall at the southern border. Under President Obama, the fight was over appropriating funding for the Affordable Care Act, his signature legislation.

This time, the messaging is not clear, making a complicated issue even harder for voters to understand.

“I would say that the messaging is bad, but that would suggest there’s a message,” Conant told The Times. “There’s no communications plan. There’s no political strategy.”

He added: “It’s just an unmitigated disaster for Republicans.”

By Saturday, House Republicans seemed to finally land on a clear objective: cutting funding for Ukraine. The House spending measure is identical to the Senate proposal, with the exception of funding for Ukraine, Rep. Mike Lawler (R-N.Y.) asserted in a speech on the floor.

“If you are telling the American people with a straight face that you would shut the government down for Ukraine, then shame on you,” Lawler said.

Earlier this week, Republicans and Democrats in the Senate sent the House a clean no-frills spending bill that included Ukraine funding. This effort was supported by McConnell. But McCarthy, bowing to conservatives, refused to give that bill a floor vote.

By Friday, he had put forth a similar bill with no funding for Ukraine.

Stripping the Ukraine money made the stopgap measure more palatable for some House Republicans, many of whom have grown hostile to sending Kyiv more military aid. Democrats and Senate Republicans remain overwhelmingly in support of sending Ukraine more money, though that position has become increasingly unpopular among the GOP base.

The fact that McCarthy and McConnell were initially on opposite sides of the shutdown battle reflects the realities that lawmakers up for reelection face, Conant said.

The Kentucky senator is focused on his party reclaiming the Senate majority. For Republicans to do that, their candidates need to be able to win in purple states, Conant said.

“McConnell recognizes the political damage that’s going to be done to Republicans by a shutdown,” he said. “He’s putting as much pressure as he can to keep the lights on.”

But in the House, McCarthy has to consider his members who are concerned about losing primary challenges from conservatives who are loyal to Trump, Conant said. Aligning with Trump and bashing an incumbent GOP lawmaker as a “Republican in name only” is a way to win in deep-red districts — and to lose in purple ones.

Times staff writer Benjamin Oreskes contributed to this report from Anaheim.