- Share via

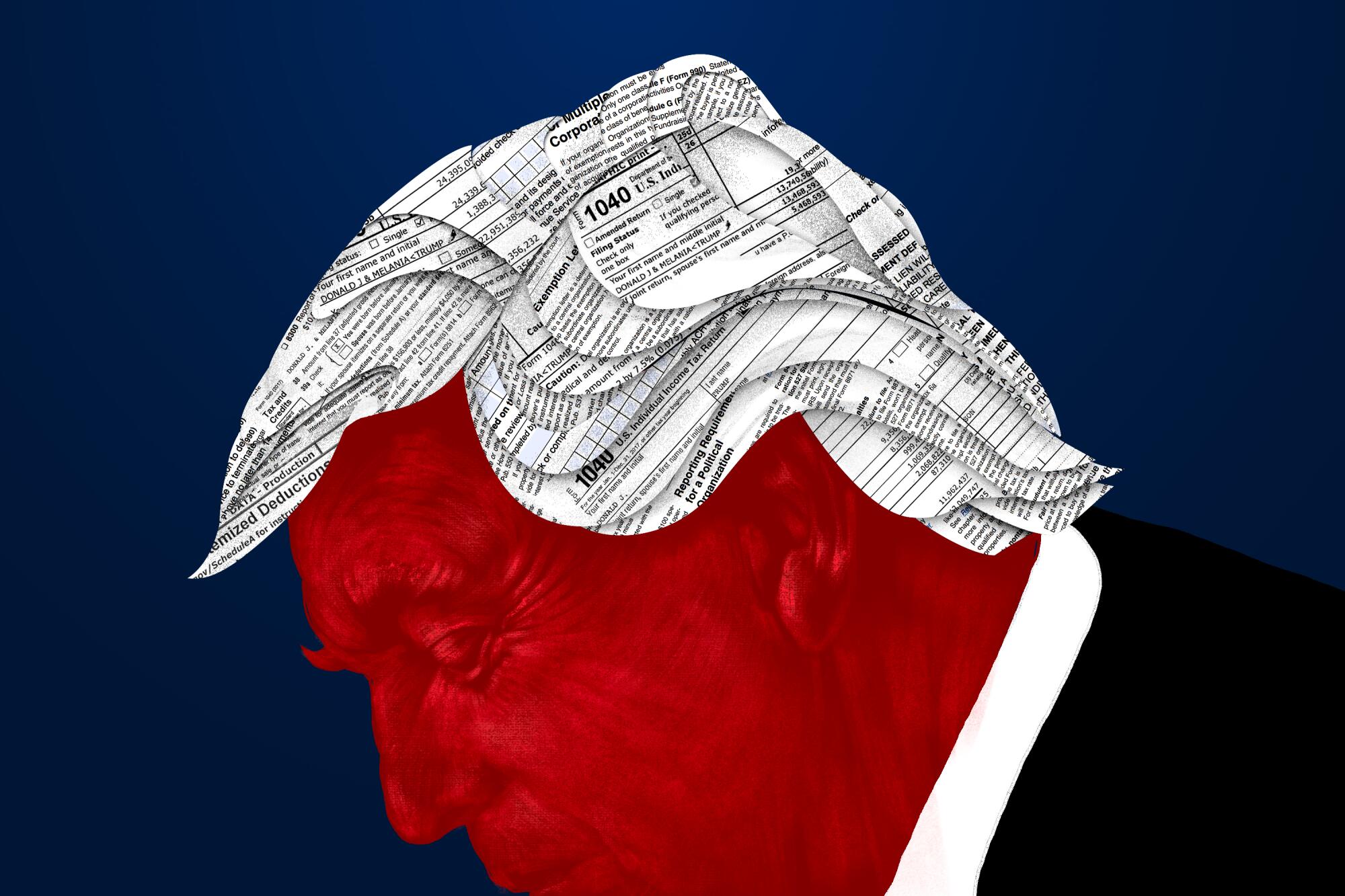

WASHINGTON — Former President Trump’s seven-year battle to keep the public from seeing his taxes ended in defeat Friday as a House committee released six years of returns documenting his aggressive efforts to minimize what he paid the Internal Revenue Service.

Trump and his wife, Melania, paid $750 or less in federal income tax in 2016 and 2017. The couple paid zero taxes in 2020 and claimed a $5.5-million refund, according to the returns released by the House Ways and Means Committee, which oversees tax legislation.

In three other years, Trump paid significant amounts. As a share of his income, however, his payments were far below those of the average taxpayer. The returns show he paid $641,931 in 2015, just under $1 million in 2018 and $133,445 in 2019.

The 2018 payment came on reported adjusted gross income of $24.3 million — an effective tax rate of 4%. By contrast, the average taxpayer in 2018 paid $15,322 in federal income taxes, with an average rate of about 13%, according to the IRS.

The release of the returns — redacted to hide Social Security numbers and other private information — marked the final act of a saga that outlasted Trump’s presidency and included two trips to the Supreme Court as Trump resisted public disclosure of his financial records. It came in the final days of Democratic control of the House.

The new disclosures do not fundamentally change what was already known about Trump’s finances — that he’s relied heavily on inherited wealth to offset a string of businesses that consistently lose money, that he’s used those losses to wipe out most of his tax liability for years, that many of his claims have stretched the law and perhaps broken it.

But the latest returns added new detail to that picture, including the disclosure that in 2020, Trump appears to have broken his pledge to donate his $400,000 annual presidential salary to charity.

“I am totally giving up my salary if I become president,” he said during the 2016 campaign. Early in his presidency, White House aides released details on where Trump had donated the money.

By contrast, his 2020 return shows zero charitable contributions. His 2018 and 2019 returns reported charitable contributions of just over $500,000. In 2017, he reported giving $1.9 million to charity. In a report on Trump’s taxes, the committee noted that Trump provided little documentation to back up those claimed contributions, a red flag.

The returns also raised questions about how the IRS handled audits of Trump’s tax filings during his presidency. Since 1977, the IRS has had a stated policy of mandatory audits of the tax returns of presidents and vice presidents. But in obtaining Trump’s returns, House Democrats discovered that during the first two years of Trump’s term, the IRS had not audited the president.

For the record:

7:51 a.m. Dec. 30, 2022An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated which year’s tax return from former President Trump the Ways and Means Committee says the IRS did not begin auditing until April 2019. It is the 2015 return.

When the agency finally did so, it didn’t dedicate enough resources to fully answer questions about Trump’s claims, the committee suggested. According to the committee, the IRS did not begin auditing Trump’s 2015 return until April 3, 2019, the day that Ways and Means Chairman Rep. Richard E. Neal (D-Mass.), sent the IRS a written inquiry. The IRS disputed that, saying it began the audit the previous year.

Trump’s returns remain under audit, and the IRS has not resolved some questions that pre-date his presidency. If the agency rules against Trump, he could face millions of dollars in additional tax liability.

It’s less likely that the former president would face criminal liability related to his taxes — the Manhattan district attorney’s office, which subpoenaed Trump’s tax returns, received them in 2018 and has brought no charges against him. The office did bring a tax fraud case against the Trump Organization, the family real estate firm, that resulted in a conviction in early December.

Republicans, who denounced the release of the returns as a violation of Trump’s privacy, are unlikely to dig deeper into Trump’s finances once they take over the Ways and Means Committee in January. But in the Senate, where the Democrats continue to have a majority, leaders of the Finance Committee have indicated they may pick up where the House Democrats left off.

The release drew a protest from Trump: “The Democrats should have never done it, the Supreme Court should have never approved it, and it’s going to lead to horrible things for so many people,” he said in a statement tweeted by his spokesperson. “The great USA divide will now grow far worse.”

During the years in which Trump battled disclosure, much of the information he sought to keep secret about his pre-presidential finances became public anyway, largely from a 2020 New York Times investigation.

The picture that emerged showed that for all Trump’s claims to be a great businessman, his core enterprises — a sprawling network of hotels, golf courses and other properties — have lost millions of dollars year after year.

“He’s a staggering loser,” said Steven M. Rosenthal, a senior fellow in the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, a think tank.

From 2015 to 2020 Trump claimed business losses between $8 million and $20 million each year, Rosenthal noted. “It’s quite astounding for somebody who purports to be rich to continue to lose so much money. Either Trump has been a very unlucky businessman or Trump’s losses are inflated. And we need to know more to determine which of those could be true.”

Trump’s golf courses in the U.S. and Scotland have been consistent money losers, the returns show. His hotel properties, by contrast, were very profitable in 2017, the first year of his presidency, but experienced large losses in 2020, thanks at least in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, which devastated the hospitality industry.

One major offset to those losses involved foreign income. In 2017, Trump’s gross income from foreign sources totaled $55.4 million. That included $6.5 million from business in China, where he made a state visit that year. He had reported no income from China in 2016. The 2017 return also shows $5.7 million in income from India. Most of the rest of the foreign income that year came from Canada. In 2018, Trump reported no income from China.

“The prospect of Donald Trump earning money from foreign interests, potentially including foreign governments, in ways that could influence his decision-making as president was one of the reasons why it was so problematic and dangerous for him to retain ownership of a large international business while serving,” said Noah Bookbinder, president of the watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “His tax returns seem to confirm that he did in fact earn millions from countries about which he had to regularly make important decisions as president.”

The returns do not disclose any obviously nefarious sources of income — contrary to speculation over the years by some of Trump’s opponents.

Trump received a large amount of income for years from his reality television show, “The Apprentice,” and from other efforts to license his name. That income had declined by the time he ran for president, but Trump also received steady income from a real estate partnership in which he has a partial ownership interest, but no management authority.

And Trump continued to benefit heavily from inherited wealth. His big tax bill in 2018 — by far the largest payment during his presidency — involved proceeds from the sale of property that he and his siblings inherited from their father, Fred Trump, including more than $14 million from the sale of Starrett City, a huge housing complex in Brooklyn that the senior Trump built.

One question the returns do not resolve is Trump’s net worth. As a presidential candidate in 2016, Trump claimed to be worth as much as $9 billion. Forbes magazine, which estimates the size of America’s largest fortunes, said that was grossly exaggerated. This year, the magazine valued Trump’s fortune at $3.2 billion. Trump has paid a lot less in taxes than other top billionaires, studies have found.

One widely used strategy that Trump took extensive advantage of involves carrying over losses from one year to reduce tax liability in another. In 2015, for example, Trump carried over an operating loss of $105.2 million. The source of his carryover losses from 2015-18 is thought to be a $700-million loss posted by Trump in 2009. In its report, the House committee noted that these carryover losses need to be verified, and there are indications that the IRS may still be looking at whether the massive 2009 loss was valid.

Trump’s ability to zero out his tax liability highlights the extremely favorable treatment the real estate industry receives under tax law as well as strategies that he and other wealthy individuals use to minimize what they must pay.

Beyond the carryover losses, the returns show a pattern of questionable claims, the committee report notes.

In addition to the charitable deductions, those include large business-expense deductions that in some cases lack documentation; financial transactions with three of his children, Ivanka, Donald Jr. and Eric, that the committee report says may have been “disguised gifts”; and millions of dollars in write-offs related to an estate that Trump owns in the New York suburbs. He initially claimed the estate, known as Seven Springs, as a personal residence, then reclassified it as a business investment in 2014.

The documents released Friday indicate that the IRS is investigating the write-offs Trump took at Seven Springs, and that the agency has questioned whether Trump may have used an inflated appraisal to bolster his claim.

That’s not the only property with a questionable tax claim. In 2017, the year Trump paid a net tax of $750, his return shows he took $7.4 million in tax credits, which completely erased what he otherwise would have owed. Some of those tax credits were apparently for renovating the Trump International Hotel in Washington, which he sold after leaving office. Tax law provides for credit for investments in historic properties and for certain poor communities, but the IRS has not yet determined whether Trump’s claims were valid.

The tax returns show a number of other cases, small and large, that were flagged by congressional staff. In one schedule for the 2015 tax year, Trump reported a $50,000 speaking fee that was almost entirely offset by $46,162 in claimed travel expenses.

Repeatedly, Trump’s returns show businesses where the reported income precisely matches reported expenses.

“That seems improbable,” said Richard Prisinzano, a former veteran of the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis who is now at Penn Wharton Budget Model, a think tank.

In releasing the documents, Democrats pointed to what they described as the IRS’ failure to put enough resources into auditing Trump as evidence of possible political interference with the tax agency during Trump’s presidency.

“We anticipated the IRS would expand the mandatory audit program to account for the complex nature of the former president’s financial situation yet found no evidence of that. This is a major failure of the IRS under the prior administration, and certainly not what we had hoped to find,” Neal said in a statement Friday.

House Republicans, who will take control of the chamber next week, denounced the release of Trump’s taxes as a violation of his privacy and a dangerous precedent.

“This is a regrettable stain on the Ways and Means Committee and Congress, and will make American politics even more divisive and disheartening,” Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Texas), the senior Republican on the panel, said in a statement. “In the long run, Democrats will come to regret it.”

Democrats argued that the IRS’ failure to consistently audit Trump highlighted the agency’s lack of resources to go up against wealthy taxpayers and the lawyers and accounting firms they can hire.

Over the last 10 years, the IRS had the capacity to audit just one partnership with 100 or more partners in a year, said Prisinzano.

“I think the IRS is outgunned on this stuff,” he said.

At the Biden administration’s request, Congress this year approved a major increase in funds for the IRS, $80 billion over 10 years, mostly to improve its ability to audit wealthy taxpayers.

As a candidate and then as president, Trump repeatedly used the claim about being under audit to fend off demands that he release copies of his returns. Every previous president and major-party candidate dating to President Carter had voluntarily released their tax returns.

Trump’s effort to keep his taxes secret began to crumble after Democrats regained control of the House in the 2018 midterm elections. A federal law dating to 1924 allows the congressional tax-writing committees to obtain copies of any individual’s tax returns — a seldom-used power, but one that provided Democrats with an opening to demand Trump’s information.

When the Ways and Means Committee asked for Trump’s returns in 2019, Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin refused, setting off a court fight that stretched across more than three years as Trump sought to block the disclosure.

In August, a federal appeals court in Washington also sided with Congress, saying that the Ways and Means panel had a valid legislative purpose in seeking to know how the IRS was handling Trump’s returns and that the disclosure of the tax information was not overly burdensome on Trump. The Supreme Court in November refused to review that ruling.

“Every president takes office knowing that he will be subject to the same laws as all other citizens upon leaving office,” the appeals court panel wrote. “This is a feature of our democratic republic, not a bug.”