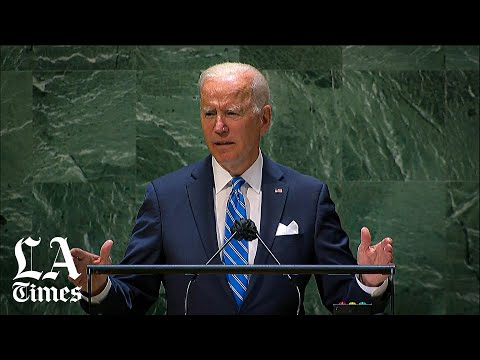

Biden tries to reassure allies and urges action on climate change, pandemic at U.N.

Biden sought to reassure allies that the United States will not turn its back on global commitments in his first speech at the United Nations.

- Share via

NEW YORK — President Biden tried to extend his global honeymoon with the international community during his first speech to the United Nations on Tuesday, promising “relentless diplomacy” now that the United States has “turned the page” on the war in Afghanistan.

In a speech that asserted the world was at the beginning of a “decisive decade,” Biden urged countries to cooperate with one another on borderless challenges like climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our security, our prosperity and our very freedoms are interconnected, in my view, as never before,” he said. “And so, I believe we must work together as never before.”

However, the specter of a world divided between the U.S. and China hung over the U.N. General Assembly, where Secretary-General Antonio Guterres opened the session by warning that the two countries’ lack of cooperation was “a recipe for trouble.”

Biden said he would work to ensure “we do not tip from responsible competition to conflict.”

“We are not seeking a new cold war, or a world divided into rigid blocs,” he said. “The United States is ready to work with any nation that steps up and pursues peaceful resolution to shared challenges, even if we have intense disagreements in other areas.”

At the United Nations summit, President Biden must attempt to repair damaged U.S. credibility and alliances after Afghanistan and amid COVID.

Diplomats have struggled to set the stage for successful negotiations over climate policies ahead of a summit later this year in Scotland, and Biden said countries must “bring their highest possible ambitions to the table.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping, who delivered a prerecorded video address on Tuesday, took a significant step in that direction by announcing that Beijing would stop supporting the construction of new coal power plants around the world. Similar commitments had already been made by South Korea and Japan, and China was under pressure to follow suit.

For his part, Biden announced that he would try to double the money the U.S. has pledged to help developing countries adapt to climate change. It wasn’t immediately clear, however, if Congress would go along with the plan; environmental proposals have repeatedly languished on Capitol Hill.

Biden’s speech represented a change from the hard-edged “America first” approach championed by former President Trump, who spent four years sowing frustration around the globe. Biden repeatedly emphasized his desire to reengage with the world through international institutions like the U.N., which had been scorned by Trump.

Despite the shift, the remarks came as controversies weaken some of Washington’s key relationships. Biden has faced criticism over his administration’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan after two decades of war, a decision that he defended as a necessary step toward refocusing the U.S. on more pressing challenges.

“We have turned the page,” he said. “All the unmatched strength, energy and commitment, will and resources of our nation, are now fully and squarely focused on what’s ahead of us, not what was behind.”

The U.S. still has troops stationed around the world and regularly launches lethal strikes on suspected terrorists, sometimes catching civilians in the crossfire. But Biden suggested he would reduce the country’s reliance on deadly force.

“U.S. military power must be our tool of last resort, not our first,” he said. “And it should not be used as an answer to every problem we see around the world.”

Biden also upset France, the U.S.’s oldest ally, by pursuing a separate defense agreement with Australia and Britain.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said the spat doesn’t mean that Biden isn’t committed to stronger ties with friends.

“Reestablishing alliances doesn’t mean you won’t have disagreements,” she said Monday. “That is not the bar for having an alliance and an important partnership. That has never been, and it’s not currently.”

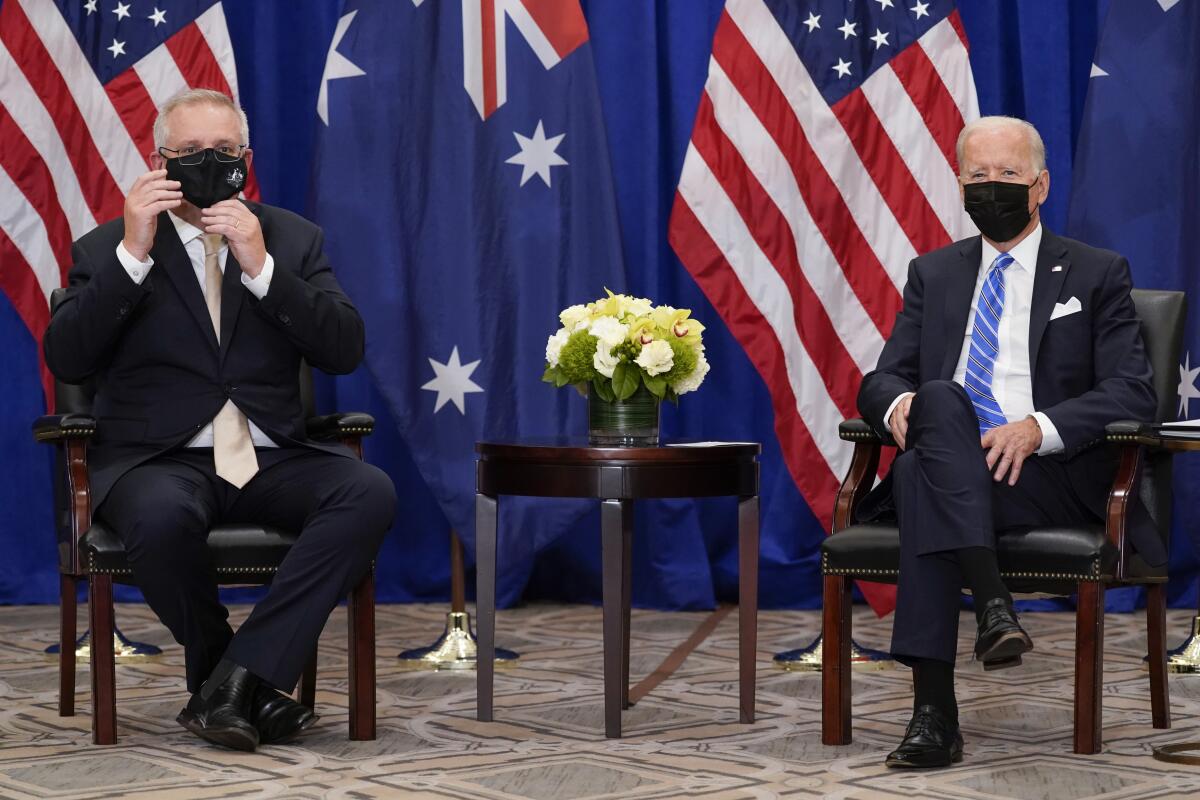

Biden held only one bilateral meeting before leaving New York on Tuesday, sitting down with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison at a hotel near the United Nations headquarters. The two leaders showered praise on each other as they discussed what Biden described as “our partnership to advance our commitment for a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

The White House is trying to arrange a phone call between Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron after diplomatic ties devolved in the last week. Although France had planned to sell diesel-powered submarines to Australia as part of a massive defense contract, the arrangement fell apart after the U.S. and Britain cut their own deal to supply Australia with nuclear submarine technology, leaving the French out of the picture.

French officials reacted to the pact — known as AUKUS, an acronym of the three countries’ names — with fierce indignation, and recalled the country’s ambassador from Washington.

Biden has other international engagements on his schedule this week. He’s participating Wednesday in a virtual COVID-19 conference, where he said he’ll announce “additional commitments” and push for more vaccines for poor countries.

While the U.S. is preparing to distribute booster shots so some eligible Americans can receive a third dose of vaccine, most people around the world have yet to be inoculated.

“President Biden must rally world leaders to end existing vaccine monopolies, waive intellectual property rules, mandate the sharing of vaccine technologies and know-how, invest in manufacturing capacity in developing countries as well as in research and development, and reallocate existing vaccine doses as soon as possible,” said a statement from Abby Maxman, president and CEO of Oxfam America, an antipoverty organization.

On Friday, Biden is hosting the first in-person summit of the Quad, another partnership focused on the Indo-Pacific. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison are scheduled to participate at the White House.

Megerian reported from Washington and Wilkinson from New York. Times staff writer Anna Phillips contributed from Washington.