Joe Biden’s Pennsylvania hurdle: Voters who fear a California-style energy plan

- Share via

PITTSBURGH — When a major airline stopped using this city’s airport as a global hub in 2004, a billion-dollar renovation project that was supposed to breathe life into the regional economy became a suffocating financial burden, and local leaders stopped looking to the sky for salvation.

Instead, they looked beneath their feet.

Hydraulic fracturing of vast stores of natural gas under Pittsburgh International Airport and thousands of surrounding acres not only bailed out an airport skidding toward default, it touched off a boom that has generated jobs and shaped the economy of southwestern Pennsylvania for two decades.

Now, the future of that boom could shape the presidential race.

Television commentary about the presidential race may focus on the future of the Supreme Court and other national questions, but in the states that will actually decide the election, local issues often matter more. In this corner of America, that means fracking.

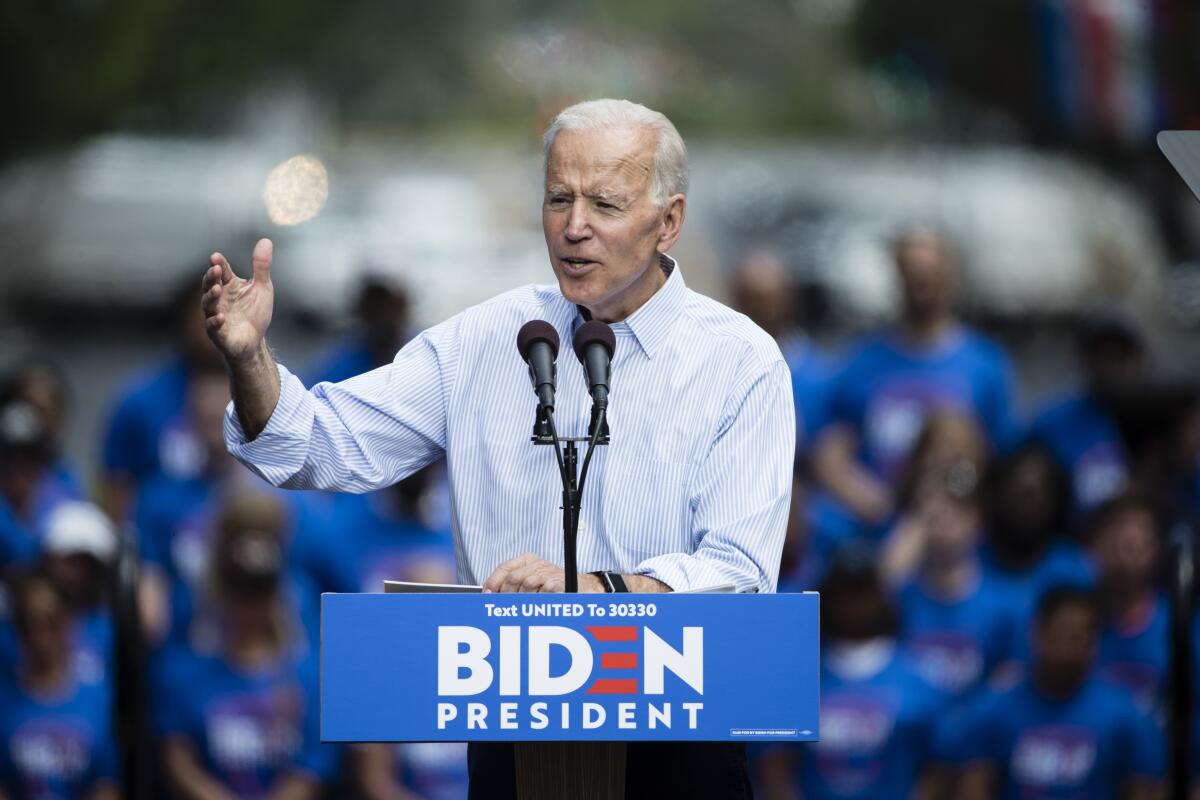

Voters whose economic well-being depends on extracting natural gas are extremely skeptical of any politician who would inhibit it. President Trump is doing everything he can to exploit those worries, taking aim at Joe Biden’s plan to rapidly phase out fossil-fuel power plants to brand the Democrat as a threat to the region’s energy boom.

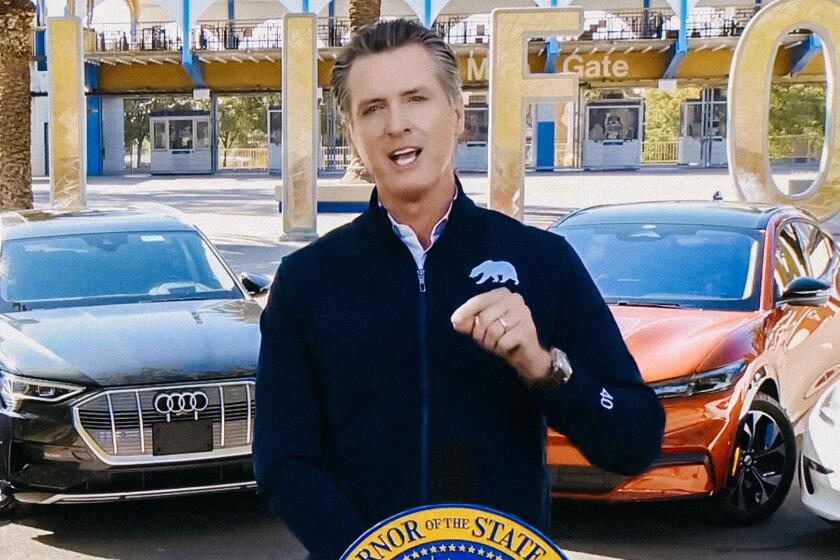

Biden doesn’t support a ban on fracking on private property, where all the fracking happens in Pennsylvania. But he does want to stop the procedure on federal lands, which would have more impact in the West and be a blow to the broader industry. Biden’s running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, has been a vocal proponent of outlawing fracking altogether, which California Gov. Gavin Newsom has now proposed as statewide policy.

Biden’s nuanced position has created tension in both directions: Even as Trump falsely accuses him of wanting to ban fracking, climate activists during the primaries attacked him for not going further. Some activists continue to press the Democrats to adopt more sweeping climate policies, regardless of the political risk.

That frustrates some Democratic leaders here, including Pennsylvania Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, who backs a gradual transition to renewable energy.

“Denying climate science is lunacy,” Fetterman said. “But to pretend we can windmill and solar panel our entire nation’s infrastructure is disingenuous and ignores reality, too.” He pointed to a recent fracking moratorium in California at the same time the state continued to rely on electricity generated with natural gas produced by fracking elsewhere.

“That doesn’t make you an eco-warrior, it makes you a hypocrite,” Fetterman said.

California would be the first U.S. state to mandate 100% zero-emission vehicles, though 15 countries have committed to phasing out gas-powered cars.

Trump’s attacks are putting the area’s Democratic leaders on edge as they scramble to help Biden cling to a modest lead in a state that he badly needs to win.

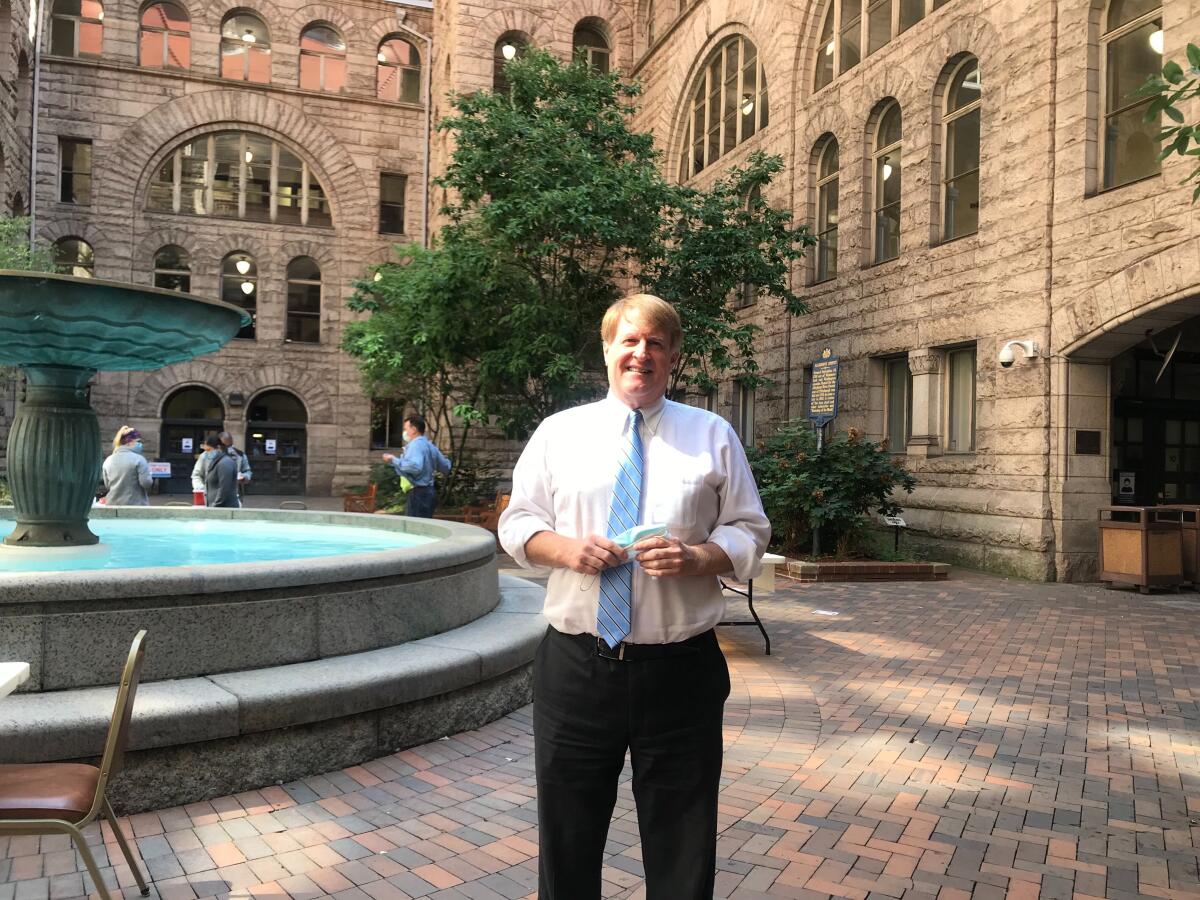

“Fracking really saved us,” said Rich Fitzgerald, a Biden supporter and the county executive for Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh, as he lead a reporter on a tour of the area by the airport. A lifelong resident of the region, Fitzgerald lived through the tough decades starting in the 1980s when the steel mills closed, and the lack of jobs triggered a mass out-migration of young workers.

“There were no opportunities,” Fitzgerald said. Fracking “changed everything. I mean literally. It brought tons of wealth into the community. We actually had people coming here from other places.”

Not just to work in natural gas. The flow of wealth from the industry positioned the region to make infrastructure investments that attracted technology innovators and drew big corporations like Amazon, Uber and Dicks Sporting Goods to build and expand campuses in the area.

Fitzgerald has implored the former vice president to keep hammering home the point that Biden made explicitly during a recent speech in Pittsburgh: That he has no plans to ban fracking in Pennsylvania.

“He needs to continue doing it,” he said.

Trump’s unexpected victory in 2016 depended heavily on a big win in southwestern Pennsylvania. Biden has helped Democrats gain ground since then. The outcome in the state may hinge on whether he can hold onto it.

“One reason Biden has the lead in the state right now is because Trump is not winning southwest Pennsylvania by nearly as much as he did in 2016,” said G. Terry Madonna, director of the Franklin and Marshall College Poll of the state. “But it is hard to say how much voters trust Biden on this issue.”

The politics of the issue are complex. Statewide, voters are evenly split on a fracking ban, and Biden’s robust climate-action plan has helped energize voters he needs in the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh metropolitan areas. The key for Biden, party strategists believe, is to maintain a carefully balanced approach, even if that frustrates activists on both sides.

Many top Democrats in Pennsylvania were relieved when Biden, a native of Scranton, won the nomination. He was one of the few Democratic contenders who did not champion a national fracking ban. His close ties to unions are helping Democrats rebuild some of the coalitions Trump managed to erode. Biden regularly ventures into rural areas that local leaders say Hillary Clinton avoided in 2016.

“We used to call him Pennsylvania’s third senator because of his growing up in Scranton and Delaware being right next door, and he just has a natural affinity for what our western Pennsylvania values are,” said Fitzgerald.

But the challenge Biden continues to face is clear while talking to voters near a sprawling construction site 20 miles north of the airport, close to the banks of the Ohio River. The multi-billion-dollar Royal Dutch Shell petrochemical plant being built there will produce 1.6-million metric tons of plastic pellets annually for such things as cellphone cases and food packaging. The plastics are made with a byproduct of the fracking process.

Construction of the plant has created more than 8,000 well-paying construction trade jobs.

“Bless it, they need the jobs here,” said Ron Richardson, a 58-year-old lifelong Democrat who plans to vote for Trump. Richardson is not impressed by Biden’s support for the plant and his vows not to ban fracking.

“Why did Biden all of a sudden start saying he likes it and everything?” Richardson said of fracking. “He did nothing but talk bad about it...Now, all of the sudden it’s getting closer to the deadline, his attitude on a lot of things has changed. And I am a Democrat.”

The Trump campaign and his allies are working tirelessly to seed such skepticism.

“Don’t forget, I am not the candidate … that said, ‘We are not going to have fracking, we are going to ban fracking,’” Trump said at a rally outside Pittsburgh on Tuesday night, alluding to a gaffe Biden made during a primary debate that he later walked back. “Then all of a sudden, he said, ‘Maybe I will have some fracking.’ And you know that won’t last because the radical left won’t let them get away with it. I am all for fracking.”

Industry leaders remain uneasy with Biden’s agenda, which may help amplify Trump’s allegations.

“We don’t get a very warm feeling from the former vice president when he says he wants to ban hydraulic fracturing on federal land and eliminate all fossil fuel use by 2035,” said David Spigelmyer, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition.

“He has a vice presidential nominee who has absolutely said she would ban it. He has placed folks on his energy policy team who are hugely against our industry without knowing what it provides to the public.”

Spigelmyer said he was hopeful that Biden would address these issues at a major fracking-industry conference next week. But Monday the Biden team relayed the news that the vice president won’t be attending the conference, which Trump headlined last year.

Trump’s failure to make good on some key promises, such as reviving the region’s coal and steel industries, are helping Biden here. But if there is one political tactic the president is skilled at, it is creating confusion and doubt.

And this region, where people have grown accustomed to living in fear of economic collapse, is particularly vulnerable to that, said Veronica Coptis, executive director of the Center for Coalfield Justice, which advocates for southwest Pennsylvania residents dealing with the environmental damage caused by coal and gas extraction.

“When we’re getting feedback,” she said, “we hear uncertainty from people on whether they can trust the information they are being bombarded with from both parties.”

Mehta reported from Pittsburgh and Halper reported from Washington. Times staff writer Anna Phillips contributed to this report from Washington.