Supreme Court confirmations are a political minefield. Few know that better than Joe Biden

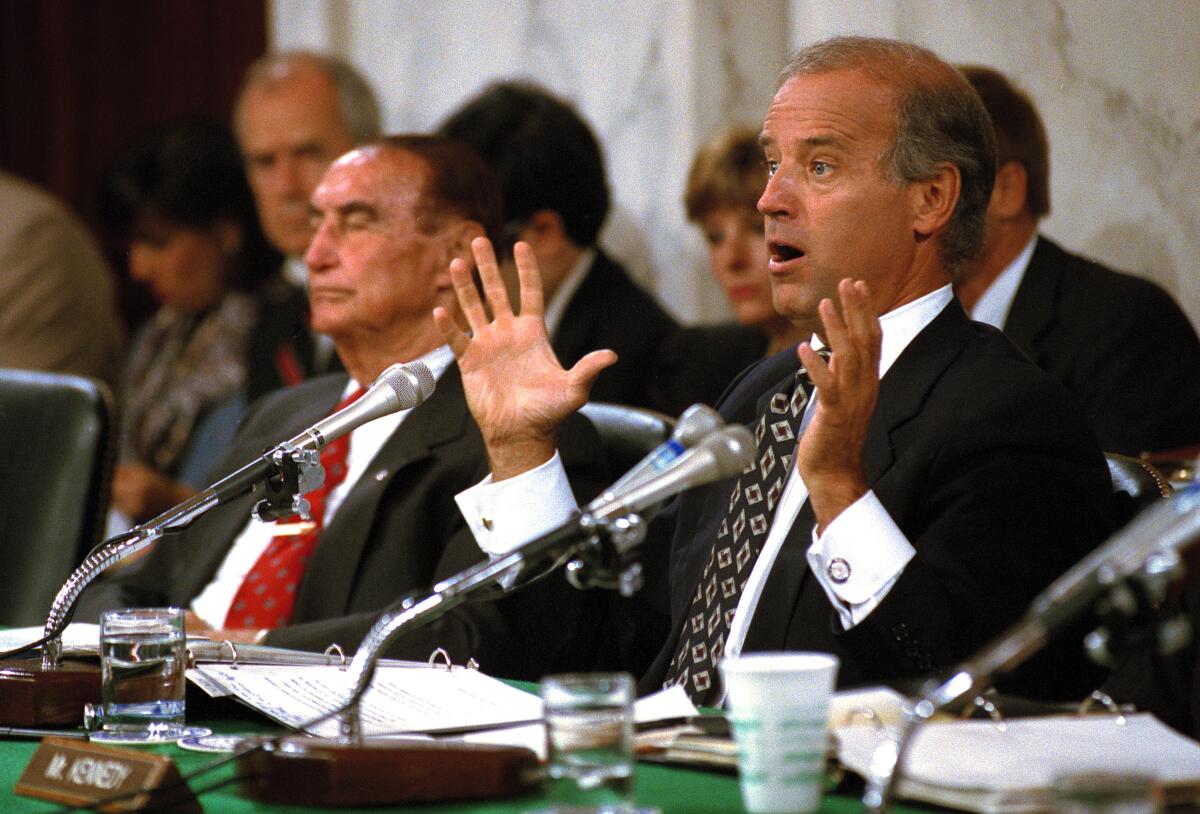

The start of the confirmation hearings to put Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the U.S. Supreme Court was nowhere to be found on the New York Times’ front page. Joe Biden couldn’t have been more thrilled.

“My heart sang,” said Biden, then chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. He declared the muted media coverage — an indication of the dearth of controversy surrounding the liberal jurist — was the “most wonderful thing that had happened” since he became head of the powerful panel.

He was right to predict smooth sailing; Ginsburg ultimately won the approval of 96 senators, and Biden, in helping shepherd her confirmation, had made yet another imprint on the nation’s courts.

The 1993 ascent of the second woman to the Supreme Court was hardly the only impact Biden made on the courts, though not all came so smoothly. As his tongue-in-cheek remark implied, his work on confirming judges was marked just as much by rancorous controversy as bipartisan comity.

His decades-long tenure on the Senate Judiciary Committee yielded some of the most significant liberal victories of his career and missteps that continue to dog him as the Democratic presidential nominee. In all, Biden has been involved with at least 15 Supreme Court nominations during his tenure as senator and vice president. If elected, he would enter the Oval Office with more experience in confirming judges than any president in the modern era.

Increasingly confident Senate Republicans are making plans to confirm President Trump’s soon-to-be-named pick to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and reshape the court.

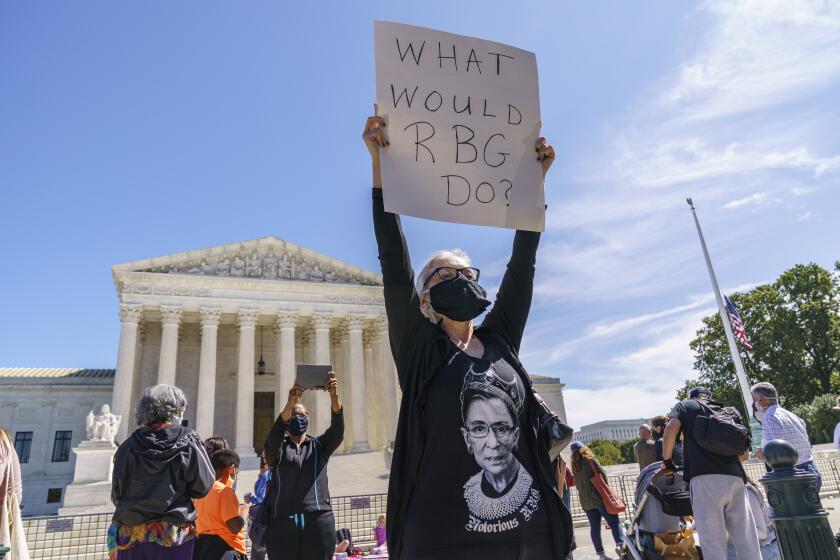

The judiciary has leapfrogged to the forefront of the 2020 race with Ginsburg’s death Friday.For most of the campaign, Biden had been largely quiet on the matter of judges, even as his rival, President Trump, touts his success in judicial confirmations, including two Supreme Court justices. While Trump has put out a list of potential court nominees, Biden’s public commitments have focused less on names and more on diversity and broad liberal principles.

“As president, he will nominate the first Black woman to the Supreme Court and appoint judges who share his commitment to the rule of law, uphold individual civil rights and civil liberties, and respect foundational precedents like Brown v. Board of Education and Roe v. Wade,” said Jamal Brown, national spokesman for the Biden campaign.

As he moves toward formally entering the Democratic presidential race, Joe Biden has repeatedly expressed regret for how he handled one of the most consequential challenges of his career in the Senate — the 1991 hearings into Anita Hill’s sexual harassment allegations against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.

The campaign declined to make Biden available for an interview. But a review of his vast experience, including 17 years as the top Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, as well as interviews with nearly two dozen former colleagues, ex-staffers and outside legal experts offer hints to how he would approach judicial nominations in the White House.

“The battle about to engulf the country is an ongoing war to control the courts,” said Michael Gerhardt, a University of North Carolina law professor who has worked extensively with the Senate Judiciary committee. “Joe Biden is as steeped in that and understands that as well as anyone.”

::

Biden, a lawyer by training, had his eye on the Judiciary Committee from the moment he was elected to the Senate at age 29. Five years later, he landed a spot on the panel, joining legislative stalwarts such as Massachusetts Democrat Edward M.

Teddy

Kennedy, a liberal lion, and South Carolina Republican Strom Thurmond, a conservative segregationist.

His rise in influence on the committee coincided with President Reagan’s administration. Some of his clashes over the president’s nominees centered on civil rights. In 1986, for instance, he helped block Jeff Sessions from a federal judgeship because of the future attorney general’s racially insensitive comments and allegations he improperly prosecuted civil rights leaders in Alabama.

But a broader fight was brewing over judicial philosophy. Reagan’s attorney general, Edwin Meese III, laid down the marker in 1985 that the administration would advance the theory of “original intent,” in which judges would narrowly interpret the Constitution based on the understanding of the framers. The philosophy left little room for rights not expressly articulated in the Constitution, such as a right to privacy, and liberals feared it would threaten much of the civil rights gains of the preceding decades.

When Antonin Scalia — one of the most prominent advocates of the theory — was up for confirmation to the Supreme Court in 1986, Biden and fellow Democrats put up little fight, aiming their efforts instead on stopping William H. Rehnquist from ascending to chief justice. They failed to do so.

Biden and his staff knew the ideological battle was just getting started when he became committee chairman in 1987. Being in the majority posed its own challenges: Biden had to corral Democrats who ranged from progressives such as Kennedy to conservative Southern Democrats, in addition to moderate Republicans who could be coaxed to cross party lines.

“That was no easy feat,” said Nan Aron, president of Alliance for Justice, a progressive judicial advocacy group.

The high-profile post provided a springboard for Biden’s first presidential run, and his two roles — candidate and chairman — collided in the summer of 1987, when Reagan nominated Robert Bork, a conservative judge and a godfather of originalism, to replace Lewis Powell, a moderate Supreme Court justice. Adding Bork to the bench would yank the court far to the right, and Biden had warned the White House that the nomination would meet fierce pushback.

Years earlier, Biden had said he was open to supporting Bork, just as he did Scalia. But now he said a deeper dive into Bork’s writing pushed him to oppose the nominations on ideological grounds. It was a departure from how judicial confirmations were largely handled in the past, which centered on the nominee’s legal competence and character. Biden and his allies made the argument that if the president was openly trying to shift the political tilt of the court, it was fair game for the Senate to focus on ideology as well.

Kennedy famously launched an attack from the left, warning that “Robert Bork’s America” would mean a return to back-alley abortions and segregated lunch counters. Biden, meanwhile, tacked more to the center, arguing that Bork’s legal theory could lead to overturning precedent that upheld a married couple’s right to buy contraception.

Bork was ultimately rejected by 58 senators, including six Republicans. For Biden, the lengthy committee hearings offered a badly needed win after he abruptly dropped out of the presidential race amid a plagiarism scandal.

“It was an extraordinary seminar for those 12 days on constitutional history and constitutional interpretation,” said Ralph Neas, a civil rights leader who worked closely with Biden. “It was phenomenal in terms of substance.”

Conservatives saw the attack as a smear campaign and few future nominees were as expansive in sharing their political views for fear of “getting Borked.”

“It was an orchestrated attack — an innovation, an escalation and most people consider it to be the start of the modern judicial wars,” said Ilya Shapiro, director of the Robert A. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies at the Cato Institute, a Libertarian think tank.

Biden’s allies point to the domino effect of the Bork debacle as one of his great achievements. Instead of an archconservative, Reagan ultimately nominated Anthony M. Kennedy, a moderate swing vote on the Supreme Court. Three years later, George H.W. Bush, hoping to avoid a similar battle, nominated David H. Souter, a centrist who ultimately became a reliable liberal vote.

“In defeating Bork and getting Anthony Kennedy in, we preserved a moderating force on the court for 30 years, which preserved Roe v. Wade and led to the gay marriage decision,” said Mark Gitenstein, chief counsel for the Judiciary Committee during that era.

Biden hoped to repeat that winning formula when Bush nominated Clarence Thomas in 1991. But civil rights groups were divided on going after a Black nominee, and Thomas did not have nearly the extensive record to pick apart as Bork did.

Anita Hill’s allegations against Thomas of sexual harassment threw those proceedings in further disarray. Biden infuriated Republicans by reopening the hearings to Hill’s testimony, and angered liberals by not fully investigating her allegations.

Shapiro said the episode was one of total political miscalculation.

“He tried to please everybody during the Thomas hearing and ended up not pleasing anyone,” he said.

Hoping to make up for the optics of an all-male panel grilling Hill on harassment, Biden recruited two newly elected female senators in 1992 to join the committee — Sens. Dianne Feinstein of California and Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois. The latter, the first Black woman elected to the Senate, was wary of the assignment at first.

“I told this joke that he did not like at all: ‘You just want Anita Hill on the other side of table,’” Moseley Braun said. “He didn’t think it was so funny. I thought it was hilarious.”

::

The acrimony of the Bork and Thomas hearings clearly weighed on Biden; in June 1992, he gave a 90-minute speech lamenting the state of judicial nominations and portraying himself as battered by criticism from both sides of the political spectrum.

“The confirmation process has been infected by the general meanness and nastiness that pervades our political process today,” he said. He also said that if a Supreme Court vacancy occurred before the upcoming presidential election, no nominee should be named until after the election, a pronouncement the GOP threw back at him when they refused to consider President Obama’s nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, in 2016.

Yet for all the attention on high-profile ideological battles, the vast majority of confirmations under Biden were straightforward and short on drama.

“It’s easy to look back and think the Bork nomination and then Thomas characterized that whole period, but those were the rare exceptions,” said Thomas Jipping, a longtime Judiciary staffer for Sen. Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah) who now works at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.

Democrats have historically struggled to make the courts a mobilizing issue, unlike Republicans. The death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg may change that.

When Gregory Sleet was nominated in 1998 to the federal district court in Delaware by President Clinton on Biden’s recommendation, he braced for a combative hearing because the GOP was in the majority. Instead, the proceedings, led by Hatch, were “anything but contentious” and he was easily confirmed as the first Black judge on that court — thanks in part, he said, to Biden’s warm working relationship with the Utah senator.

“These relationships that Biden had seemed to enable him to move fairly seamlessly from one side to the other in the interest of compromise and getting things done,” said Sleet, who retired from the bench in 2018. “I think that probably helped him get judges confirmed.”

Allies say Biden was not particularly dogmatic in assessing judges, relying largely on a nominee’s legal qualifications and background checks, and prioritizing diversity and life experience.

“He was looking for intellect and character,” said Moseley Braun. “The way it was expressed was a good head and a good heart. He wasn’t somebody that had an ideological litmus test.”

At times, that meant siding with the GOP over members of his party. As chairman, Biden went ahead with the confirmation hearings in 1989 for Vaughn Walker, a San Francisco attorney who had been nominated by Bush to the U.S. court for the Northern District of California and supported by Pete Wilson, then the state’s GOP senator.

The state’s other senator, Democrat Alan Cranston, opposed the choice, but Biden allowed the confirmation vote because the White House had consulted with the two home state senators before naming Walker.

“It was a very statesman-like approach,” said Walker, who later made history by ruling against Proposition 8, California’s ban on same-sex marriage.

The notion of compromise feels like a bygone relic in this hyper-politicized era of judicial nominations. The Republican-controlled Senate confirmed the lowest percentage of federal judges in decades during the last year of the Obama-Biden administration, leaving Trump with more than 100 vacancies to fill, which he has done so at a rapid clip. Democrats have voted against those nominees at historically high rates.

That dynamic became even more combustible after Ginsburg’s death. Biden, if elected, is certain to face enormous pressure from progressive groups to confirm judges and pursue more aggressive tacks, such as “court packing” — adding new justices to the high court to offset conservatives’ power.

“They understand, better than any time in history, what the stakes are for the country,” said Aron, the progressive judicial advocate.

Biden had said he opposed court packing; on Monday, he called it a “legitimate question” but did not take a position. In a recent speech on the Supreme Court vacancy, he made a direct appeal to Senate Republicans — some of whom he had worked with on courts decades ago — to not confirm a nominee before the election.

The current political crosswinds may test Biden’s faith in interpersonal relationships and consensus-building. But those closest to him say his goals remain the same as they were decades ago: to shape a center-left judiciary, or, as Gitenstein, his former counsel, succinctly put it, “rebalance the court.”

“There’s nobody better equipped to do that,” Gitenstein said. “He knows more about it than anybody who has ever held the presidency.”