Progressives fret Feinstein won’t be tough enough in handling Biden judicial nominees

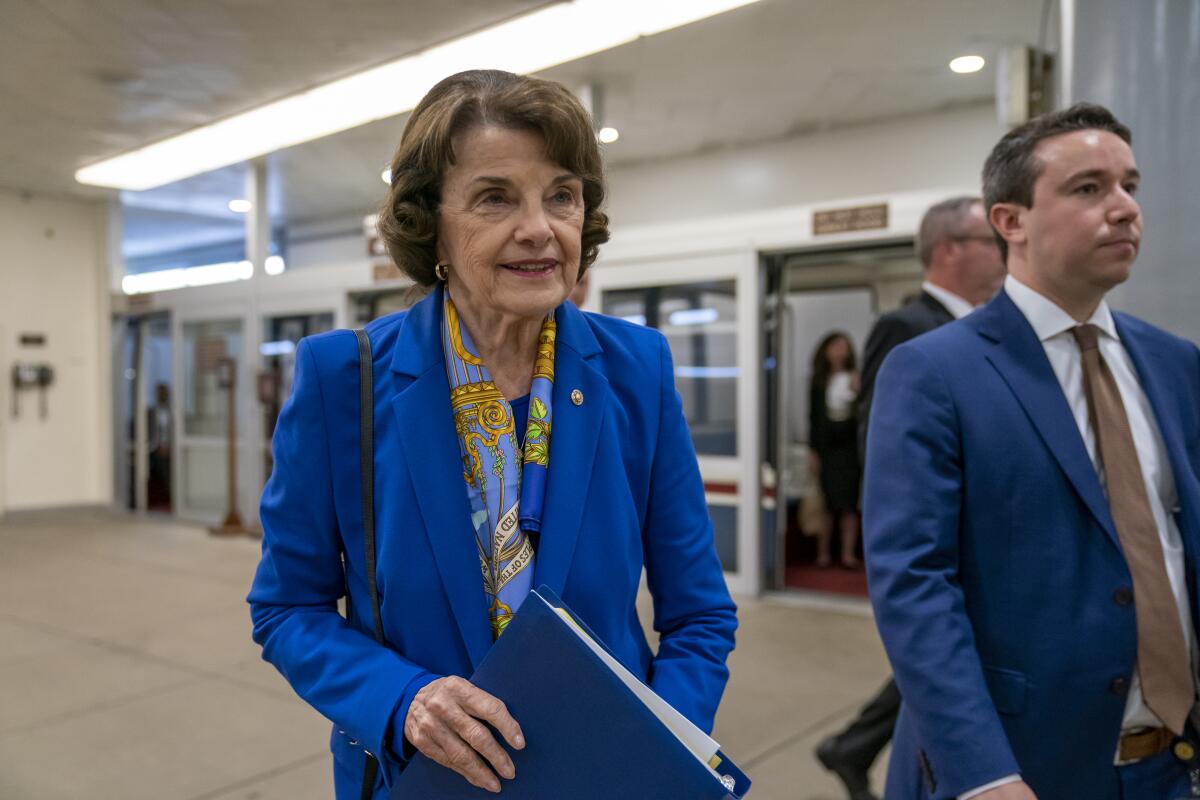

WASHINGTON — Progressives hoping for a Democratic White House and Senate next year are already voicing worries that Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who would be next in line to lead the Judiciary Committee, will not commit to pushing a future Biden administration’s judicial nominees with the same aggressive tactics used by Republicans under President Trump.

As Judiciary Committee chairman, Feinstein, 87, would wield significant political power if Democrats take control of the Senate. She would be responsible for reviewing and confirming the president’s Supreme Court nominees and other judicial appointments.

Fueling progressives’ concern is Feinstein’s refusal to say whether she would give Republicans power to block appellate appointees through a Senate practice known as withholding blue slips.

While not a rule, the century-old Senate practice allows senators who represent the home state of a judicial appointee to essentially veto a White House appointment if one of the senators — whether Democrat or Republican — doesn’t return the “blue slip” to the Judiciary Committee chair.

Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa), who led the panel during the beginning of Trump’s presidency, abandoned the practice in 2017, and moved forward with Trump administration appellate court appointees over the objections of Democratic senators. He and his successor, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), did so 17 times, including for four 9th Circuit judges over the objections of Feinstein and Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), according to a tally provided by Feinstein’s office.

Feinstein has repeatedly and forcefully objected to Republicans’ decision to abandon the blue slip policy.

But when asked in a brief interview in the Capitol last week how she would address the issue if she became chairman next year, Feinstein said she wasn’t aware of a controversy over blue slips or that Republicans had confirmed judges without them.

“I have never heard a problem. No one has — in 26 years — brought me a problem on blue slips,” Feinstein said. “I’m not aware of it. If you can bring me the objection, I’d like to know what it is.”

In a statement later provided by her office, Feinstein indicated that she has made no definitive commitment on how she would handle the issue if she is Judiciary chairman.

“I’ve objected forcefully to Republicans’ decision to abandon the blue slip,” Feinstein said in the statement. “As I’ve reminded them repeatedly, what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.”

Progressives cite Feinstein’s reluctance to embrace a similar strategy as a sign that she won’t be willing to use the hardball tactics they believe will be required to confirm judicial nominees in a Biden administration or get through increasingly contentious Supreme Court battles.

“It should be a no-brainer at this point that Democrats can’t afford to go back to giving Republicans a veto over a Democratic president’s judicial picks,” said Brian Fallon, executive director of Demand Justice, a liberal advocacy group that focuses on the courts.

“Dianne Feinstein has been railroaded in her home state of California these last few years by the Republicans, and the idea that she might just turn the other cheek and let Mitch McConnell [the Senate majority leader who would presumably become minority leader] block a President Biden’s judicial picks is basically disqualifying. And if she’s not willing to fight all-out for Joe Biden’s judicial nominees, then the Democrats ought to figure out who else can run that committee.”

Feinstein’s preference to keep her plans vague is not unusual. Several Democratic lawmakers have been reluctant to discuss detailed plans for 2021 until the election is over.

Progressives are signaling they plan to pressure Feinstein on blue slips and other issues.

“If you keep the blue slip, you’re tying at least one hand behind your back,” said Meagan Hatcher-Mays, director of democracy policy at Indivisible, a liberal advocacy group. “For her to waver on this arcane process — that does nothing but give power to Republicans in the minority — makes absolutely no sense.”

Because the blue slip is a Senate tradition and not a written rule, the Judiciary Committee chair has significant discretion over how to use it.

Under President Obama, Republicans began more frequently withholding their blue slips from nominees. At that time, the Judiciary chairmen wouldn’t advance a nominee without a blue slip from each U.S. senator representing the state. The result was that numerous judicial vacancies remained open at the end of Obama’s term, which gave Trump a chance to fill them.

In 2017, Grassley moved the first appellate court nominee that did not have blue slips from both home-state senators. Two years later, Graham advanced the first appellate nominees without blue slips from either senator. Republicans have not moved any district court nominees without two positive blue slips.

Feinstein is a Senate institutionalist who favors bipartisanship. For years, she has chastised Republican moves to abandon the practice and praised the bipartisanship that blue slips encourage.

“Blue slips are an effective way to ensure that home-state senators, regardless of party, have a say on the judges whose decisions will directly impact their constituents,” she said in the statement. “It’s a tradition that fosters bipartisan engagement in the nomination process and, until now, has been respected by chairs of both parties.”

The blue slips are just one area of Senate procedure in which Feinstein is likely to face pressure from progressives in 2021 if Democrats win control of the Senate.

With an expectation that Republicans will block any Biden administration policy, Democrats are actively considering whether to do away with the filibuster, or the requirement that most legislation have 60 votes to pass. Without it, legislation would only need 51 votes to be approved, with the vice president breaking a 50-50 tie.

Rank-and-file Democrats are increasingly open to the idea of changing the policy.

But many Democrats, like Feinstein, are skeptical of the idea because the high threshold in the filibuster prevents laws from changing rapidly when power changes hands in Washington. For instance, Republicans would have been able to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2016 without it.

“I’m not inclined to change the filibuster,” she said. “I have not yet heard a good reason to do so. I think, in a way, it’s been a very important measure in the Senate.”