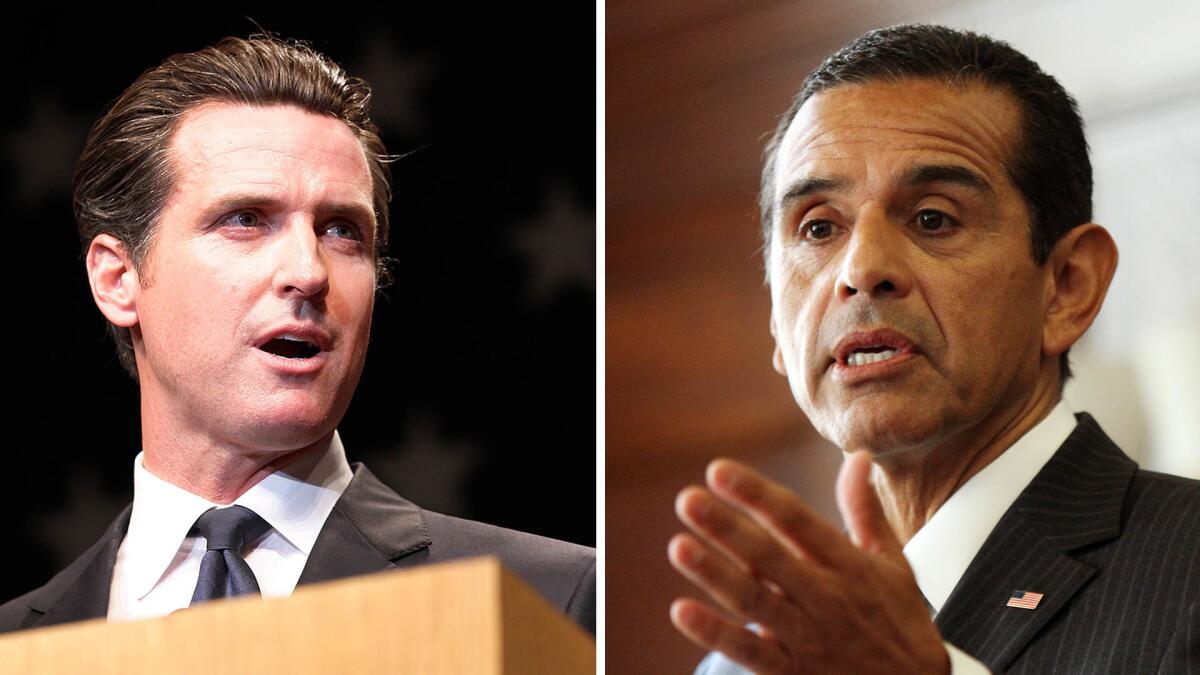

In a north-south matchup, Villaraigosa’s and Newsom’s mayoral records show how they might govern California

- Share via

The whiff of rivalry arrived almost as soon as Gavin Newsom and Antonio Villaraigosa ascended to lead California’s two most famed cities.

As the youthful mayor of San Francisco, Newsom quickly rose to national prominence with his push to legalize same-sex marriage in 2004. A year later, Villaraigosa personified the long-awaited rise of Latino political power when he took office as mayor of Los Angeles.

Each took on some of the most intractable issues confronting their cities with such an abundance of confidence and affinity for the spotlight that their showdown for California governor seemed all but inevitable.

Their work as mayor provides voters with the best glimpse of how they could govern California if elected in November, revealing how each responded when faced with the worst fiscal crisis since the Great Depression, violent crime, homelessness and calls to improve public education.

But “it’s not clear from their experiences that they’re going to have any magic solutions,” said UC Riverside political scientist Karthick Ramakrishnan, adding that the bigger question is how either would work with the Legislature — especially if the economy sours.

Villaraigosa swept into office in 2005 as a political cause celebre — the first Latino elected mayor of Los Angeles in more than a century. He appeared on the cover of Newsweek magazine under the headline “Latino Power” — a label loaded with promise and pressure.

He would go on to deliver some substantial achievements during his two terms as mayor. Hundreds of new police officers were put on the street, and violent crime plummeted, with the number of annual homicides in the city dropping from 489 in his first year in office to 251 in his last. The city’s Department of Water and Power shifted from coal-fired power plants to wind and solar, and the urban revival of Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles infused the city with a dose of young energy.

In 2008, Villaraigosa helped win voter passage of a $35-billion transportation package for mass transit projects, including the “subway to the sea” he promised in his 2005 campaign. The effort will have an indelible effect on Southern California for decades, with expanded light-rail lines and bus service to help stitch together the patchwork of communities in the Los Angeles Basin and surrounding valleys.

Villaraigosa has readily admitted that his biggest failure during his first term was a personal one. His affair with a television news anchor, which became public in 2007, ended his 20-year marriage and damaged his standing with many city voters, taking the shine off many of his accomplishments.

Villaraigosa’s most stinging political defeat came early in his first term when, in a clash with teachers unions, he tried and failed to bring the Los Angeles Unified School District under his control. He recovered by creating a nonprofit to take over a dozen struggling city schools, and he orchestrated a takeover of the school board with his political allies.

Stuart Waldman, president of the Valley Industry & Commerce Assn., was quick to criticize Villaraigosa while he was at City Hall, but now says his overall opinion of the former mayor has risen steadily. Villaraigosa’s biggest success in office, Waldman said, was keeping the city afloat during the recession that leveled Los Angeles and the rest of the nation a decade ago.

“You have to ask: Is the person who is going to be in the governor’s office capable of handling it?” Waldman said. “The one thing you can say about Villaraigosa is that there were no sacred cows. He took on the teachers union. He took on the city employees union. He made the tough choices.”

Worries about Southern California’s economic well-being and L.A.’s growing municipal budget deficit deepened in late 2007 and early 2008, just as the nation’s economy began to spiral into recession.

The fiscal outlook was especially bleak for L.A., exacerbated by city worker pay raises of 25% over five years approved by Villaraigosa and the City Council just before the recession hit, as well as Villaraigosa’s refusal to stem an aggressive expansion of the Los Angeles Police Department. By the end of his second term in 2013, hundreds of city workers had been laid off, and the city had extracted concessions from unions on pay cuts as well as pension and retiree costs.

“A combination of all those things really helped steer the city in the right direction,” said former City Administrative Officer Miguel Santana, who reported to Villaraigosa and the City Council.

Santana said Villaraigosa was under intense pressure to abandon his promise to hire 1,000 new police officers, even when he was told it would mean laying off other city workers and curtailing some city services.

“He felt restoring public safety was the city’s No. 1 issue, even in the recession,” Santana said.

Patrick McOsker, former president of the city’s firefighters union, scoffs at such praise. He accused Villaraigosa of being “dishonest and a bully” when negotiating with the United Firefighters of Los Angeles City, saying public safety clearly wasn’t a priority when it came to the city’s Fire Department.

“Fire stations were closed,” said McOsker, who is now retired. “Response times went up. We had people lose their lives.”

Everything you need to know about the June 5 primary »

Newsom’s tenure as mayor of San Francisco was full of audacious promises and mixed results.

San Francisco is powered by a tech boom that has drawn some of the brightest minds to the city, driving up housing prices and displacing longtime residents.

Just six months into office, Newsom pledged to largely end the city’s staggering homelessness crisis within 10 years.

Over that decade, $1.5 billion was spent on efforts to reduce homelessness, and nearly 20,000 people were moved off the streets, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. But the city continues to be crowded with homeless people.

Newsom was elected in 2003 as a moderate, business-friendly Democrat. But a month after taking office, he decided to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples, engendering support from San Francisco’s progressive voters. That backing paid off down the line — with support when he admitted to a sexual relationship with a subordinate who was married to a close friend, and then no real opposition when he ran for reelection in 2007.

In 2006, the Healthy San Francisco program was launched to provide basic healthcare coverage to uninsured city residents. Newsom frequently touts the effort in his gubernatorial campaign as a key accomplishment from his time as mayor. But the reality is more complicated — the coverage does not apply outside city limits and is more accurately described as access to care rather than insurance, and the idea was not Newsom’s alone.

Former county Supervisor Tom Ammiano, whom many credit as the originator of the healthcare plan, said Newsom was absent when the program was challenged by a restaurant association in a legal battle that went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The group unsuccessfully argued that the city’s plan — which required employers to provide health insurance to their employees, set up healthcare reimbursement accounts or pay into the city plan — was preempted by federal law.

“I never saw Gavin’s butt anywhere,” said Ammiano, who is backing Democrat Delaine Eastin for governor.

Jim Ross, who ran Newsom’s 2003 mayoral campaign, said the episode reflected a broader criticism of Newsom’s tenure.

“The big, bold policy programs that happened while he was mayor didn’t necessarily originate with him. Healthcare is one that comes to mind immediately,” Ross said. “He was very good at seeing where the parade was going and getting out in front of it.”

Still, he noted that Newsom, who was overwhelmingly reelected, was popular when he left office.

Newsom did “a very good job of being the mayor of San Francisco that a lot of people in San Francisco want,” said Ross, who is supporting Democrat John Chiang’s gubernatorial bid.

Newsom also inspired fierce loyalty among his supporters, who argue that he prioritized social justice and civic issues, and cite accomplishments including universal preschool, a major increase in the use of renewable energy, the massive growth of the biotech industry and mandatory composting and recycling for residential and commercial property owners.

Asked about the most significant achievements of Newsom’s tenure, his former chief of staff, Steve Kawa, replied, “You have 17 hours?”

Newsom’s mayoral terms were bookended by fiscal recoveries. He took office after the dot-com crash and oversaw the response to the Great Recession in his final years in office.

In the aftermath of the recession, the city laid off workers and reduced services but was able to bridge a record-breaking deficit, renegotiate labor contracts to win more than $250 million in concessions and avoid laying off police officers, firefighters and teachers.

Peter Ragone, a longtime advisor to Newsom who is running an independent expenditure committee supporting his gubernatorial bid, said Newsom’s approach to the recession as mayor shows how he’d govern the state.

“When there are financial crises and budget shortfalls, what most elected officials talk about is what they are going to cut and what they are going to remove from government activity,” Ragone said. “What Gavin did was he walked in and said, ‘This is what I’m going to protect at all costs.’ ”

But critics argue that this is another case of Newsom’s taking credit for the work of others.

“San Francisco has benefited from having a very, very strong and competent controller’s office, and in and around the budget there is a storied history of mayors and boards of supervisors really deferring to the city’s financial experts,” said Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who as board president clashed with Newsom when he was mayor. Peskin is backing Villaraigosa. “I think we all collectively made the right decisions … in a way that kept our bond rating and reserves and municipal finances the envy of the state.”

The city fared better in its recovery than most, and its economy has boomed since, with unemployment at 2.5%, a trajectory that San Francisco Chamber of Commerce Senior Vice President Jim Lazarus credits to Newsom. Lazarus, a former City Hall aide who never worked for Newsom, is supporting the lieutenant governor’s gubernatorial bid.

“While he was mayor, his office of economic and workforce development put out a plan that really focused on the obvious strengths of San Francisco — a knowledge-based economy and tourism,” Lazarus said.

During their terms as mayor, both Newsom and Villaraigosa were mocked for enjoying the adulation of the television cameras. Both had a reputation for being thin-skinned. Newsom was criticized for the large size of his media staff and proliferation of City Hall czars. Villaraigosa took heat for the high turnover among his top aides.

How the two men worked with local government as mayor offers insight into how they would approach the state Senate and Assembly if elected governor.

Newsom’s relationship with the San Francisco Board of Supervisors has been described as contentious and combative. Peskin said that was the result of Newsom’s not being around much and not keeping promises.

“The coin of the realm is your word,” Peskin said. “My fellow supervisors would joke, if [Newsom] said he was going to vote for a piece of legislation and you had his vote, yes could mean no, no could mean yes, maybe could mean no or yes.”

Villaraigosa, a former Assembly speaker and city councilman, was known to work collaboratively with the City Council with only rare blowups, including one over Villaraigosa’s proposal to increase utility rates to pay for more renewable energy, said Republican Councilman Mitchell Englander, who represents the northeast San Fernando Valley.

“The bottom line was that he was transactional. While there were disagreements, he was always willing to come to the table,” Englander said. “To accomplish anything as mayor of L.A., you can’t do it alone.”

Inside the mayor’s office, Villaraigosa could be impatient and occasionally short-tempered. He has been known to scold staffers in public or in front of their colleagues. Jeff Carr, who served as his chief of staff, dismissed that, saying Villaraigosa was a demanding but fair person to work for.

“He was very effective at communicating what he thought,” Carr said. “Whether that was good or bad, you never had any doubt where you stood with him.”

In Los Angeles and San Francisco, Villaraigosa and Newsom had two very different cities over which to preside.

In 2010, when both Villaraigosa and Newsom were in the mayor’s office, Los Angeles had a population of 3.8 million, 21.6% of whom lived in poverty, according to the U.S. census. San Francisco had a population of 805,000, 12.5% of whom lived in poverty. Latinos accounted for 49% of residents in Los Angeles and 15% of residents in San Francisco.

But the divide goes beyond demographics, said Dan Schnur, professor at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

“San Francisco has such a deep, ingrained political culture and history of community involvement that the mayor’s job is something between a traffic cop and a recess monitor. And for all sorts of reasons, Los Angeles doesn’t have that culture because it’s such a more geographically spread-out area, and such a more diverse community,” said Schnur, who has lived in both cities. “The job of a Los Angeles mayor is to get people to pay attention. The job of San Francisco mayor is to get people to calm down.”

Coverage of California politics »

Twitter: @philwillon

Twitter: @LATSeema