The latest Nobel laureate’s work is haunted by questions. Don’t expect answers

- Share via

Book Review

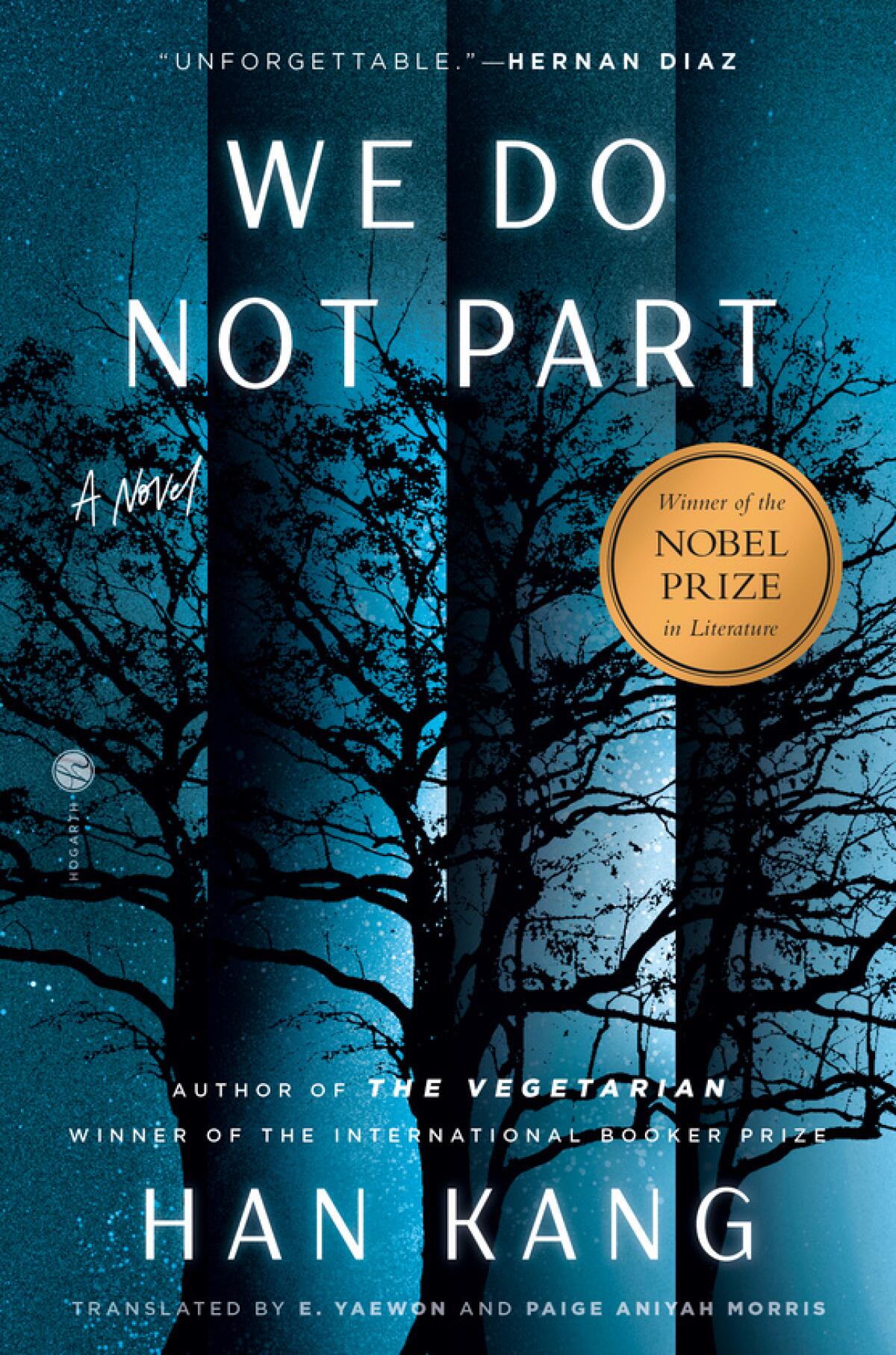

We Do Not Part

By Han Kang

Translated by E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris

Hogarth: 272 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In a 2024 speech accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature, South Korean author Han Kang confessed that “I had long lost a sense of deep-rooted trust in humans.” She wondered: “How then could I embrace the world?” Grappling with existential angst is a thread that runs throughout Han’s fiction, most notably in the Man Booker-winning “The Vegetarian,” in which the main character renounces meat and eventually believes she’s turning into a plant.

Han’s exquisite and profoundly disquieting latest novel to be translated into English, “We Do Not Part,” also attempts to probe that elemental dilemma. Her elusive protagonist, Kyungha, too has undergone a metamorphosis. In the course of her research for a book on victims of the deadly Jeju Uprising of 1948, she finds she is no longer able to reconcile the inhumanity she’s confronted with a belief in the goodness of people. “Having decided to write about mass killings and torture,” she reflects, “how could I have so naively — brazenly — hoped to shirk off the agony of it?” Four years on, she’s finished the book but remains haunted by its subjects. As a result, “a desolate boundary has formed between me and the world.”

When we first encounter Kyungha, she’s left her job and ceased contact with most family and friends. Her private life has crumbled “like a sugar cube dropped in water.” She’s spent months shrouded in gloom, cocooned in a flat outside Seoul, rarely rising from bed. Excruciating migraines leave her without energy or appetite; nightmares pervade her sleeping hours. One dream is more vivid than the others. It unfolds on a snowy seaside hill under which countless bodies have been buried. Waves crash over their shallow graves, which are marked by thousands of tree trunks jutting from the ground like “black torsos.” Kyungha’s preoccupation with this image leads her to reach out to Inseon, a documentary filmmaker friend with whom she hopes to collaborate on a project memorializing that vision.

Inseon has moved from Seoul to the volcanic island of Jeju to care for her dying mother, who herself was traumatized by a government-backed massacre that left 30,000 dead. After her mother dies, she remains in her childhood home, working as a carpenter. One day Kyungha receives a text from Inseon, who’s suffered a gruesome accident while woodworking and is hospitalized in Seoul. She pleads with Kyungha to fly immediately to Jeju to care for her pet bird, a favor Kyungha agrees to do, though a blizzard makes getting there nearly impossible.

Snow is a character unto itself in this novel, symbolizing both beauty and danger: “As the snow lands on the wet asphalt, each flake seems to falter for a moment. Then, like a trailing sentence at the close of a conversation, like the dying fall of a final cadence, like fingertips cautiously retreating before ever landing on a shoulder, the flakes sink into the slick blackness and are soon gone.” Han’s prose is translucent, shot through with poetic turns.

A bus from the Jeju airport can transport Kyungha only so far, and she is left to stagger through snow banks to reach the remote hillside cottage while darkness descends. Freezing and disoriented, she burrows down, curling herself into a tight ball. Nearly losing consciousness, she forces herself to rouse: “I had to plunge my legs in, then pull them back up to walk through the snowdrifts. … The trees around me were increasingly sunk in nightfall and half smothered with snow. … I moved forward, the sound of my legs trampling in and out of the snow the only thing to shatter the hush of the evening.” Finally, Kyungha spots the glow of a lantern and enters Inseon’s workshop.

While alone in her apartment, Kyungha had seemed to hover between hallucination and reality; on Jeju, the line between the two evaporates. The storm rages outside, while inside, there is no power. The fate of the bird is uncertain. Kyungha has a premonition that Inseon’s condition has grown dire, but then her friend appears to her — an apparition. At first Inseon is only in silhouette, until: “The black, rounded form shuddered and grew long. The body was extending itself out of its huddled pose. … Its face, which had been buried in its arms, turned toward me.” And then a voice rasps: “Kyungha-ya.”

The two settle into conversation, as if nothing strange is happening. Inseon assumes the role of host, making tea and lighting candles. They sit comfortably across from one another at the kitchen table. Intermittently, though, Kyungha is aware that her friend’s presence may be an illusion, and that the real Inseon may be dying in her hospital room. We, too, become confused, no longer able to discern the real from the surreal.

In the sections that follow, the language shifts in tone, becoming reportorial, as Inseon narrates the saga of her family’s tragic history as witnesses to and victims of the Jeju massacre. It becomes clear that this is her mission in appearing to Kyungha: Her friend must bear witness. When Inseon finishes chronicling their tale, she seems to vanish. Kyungha now senses the presence of someone or something that might or might not be Inseon. She wonders: “Is that someone you?”

Han has observed that each time she works on a book, “I endure the questions, I live inside them. When I reach the end of these questions — which is not the same as when I find answers to them, is when I reach the end of the writing process. By then,” she says, “I am no longer as I was when I began.” Her characters experience similar transformations.

I found no answers in this deeply mysterious and often eerie novel. To read “We Do Not Part” is to inhabit an unknowing. Whether Han’s characters live or die or exist in a liminal space remains a puzzle. We won’t learn whether Kyungha is one day able to transcend her grief or revive “the wiring inside me that would sense beauty,” or whether Inseon can survive her grave injuries. But Han’s radiant intensity, her singular ability to find connections between body and soul and to experiment with form and style, are what makes her one of the world’s most important writers. From something as simple as the strike of a match, she can compose these words: “Up leaped a flame. Like a blooming heart. Like a pulsing flower bud. Like the wingbeat of an immeasurably small bird.”

As to how Han processes despair but doesn’t surrender to it: “I understood that writing was my only means of getting through and past it. … Could it be that by regarding the softest aspects of humanity, by caressing the irrefutable warmth that resides there, we can go on living after all in this brief, violent world?”

Leigh Haber is a writer, editor and publishing strategist. She was director of Oprah’s Book Club and books editor for O, the Oprah Magazine.